Approach

Splenomegaly may be noted incidentally on physical examination or on imaging, or as a feature of a known or suspected entity such as hepatic, infectious, immunological, or traumatic disease.

History

Constitutional symptoms

A history of fevers, night sweats, or weight loss (B symptoms) suggests lymphoma, leukaemia, or infective endocarditis. However, some patients with lymphoma or leukaemia are asymptomatic. Clinical history in patients affected with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) - both B-cell and T-cell - depends on the type of lymphoma and the stage at presentation. Although low-grade NHL is often minimally symptomatic or asymptomatic, high-grade NHL may present with B symptoms. Patients with T-cell lymphoma can also present with B symptoms. Patients with polycythaemia vera evolving to a 'spent phase' may also exhibit B symptoms. In addition, fatigue and weight loss, accompanied by arthralgias, may be found in autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Fever may be a late symptom in primary sclerosing cholangitis (caused by episodic bacterial cholangitis). Fever can be seen with any of the infectious aetiologies leading to splenomegaly. Weight loss may occur in amyloidosis.

Abdominal symptoms

Patients may present with a history of abdominal pain, particularly left upper quadrant (LUQ) pain, in addition to other symptoms. Rarely, alcohol-induced pain is reported in the spleen area in Hodgkin's disease. Symptomatic chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) includes abdominal fullness and LUQ pain. In chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML), LUQ pain and/or early satiety indicates an extremely enlarged spleen. Patients with splenic vein thrombosis may report LUQ, epigastric, or generalised abdominal pain, including symptoms of acute pancreatitis. The onset of splenomegaly can be rapid and painful. Patients with splenic metastasis may report LUQ pain at presentation, in addition to the symptoms of the primary neoplasm (e.g., weight loss, cough, or change in bowel habits). Benign splenic tumours are often asymptomatic, and no unusual history of pain or abdominal swelling is reported.[15] Right upper quadrant (RUQ) pain may be a sign of chronic liver disease.

Pruritus

Generalised pruritus may be seen in Hodgkin's disease or T-cell lymphoma; aquagenic (evoked by contact with water) pruritus can occur in polycythaemia vera. Furthermore, in the early phases of chronic liver disease (e.g., due to hepatic steatosis, primary biliary cholangitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis), patients may present with pruritus in addition to fatigue, malaise, and RUQ discomfort. Later stages are characterised by jaundice and stigmata of cirrhosis.

Lymphadenopathy

Lymphadenopathy occurs in lymphomas and leukaemias (T-cell and B-cell NHL, Hodgkin's disease), immune disorders (sarcoidosis, rheumatoid arthritis, SLE), and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection. Several months of persistent adenopathy may be reported in Hodgkin's disease. Rarely, patients may present with shortness of breath, cough, chest pain, abdominal pain, or face and/or arm swelling due to enlarged lymph nodes.

Sex and age

Sex and age may provide important diagnostic clues when interpreted with other historical findings. Female sex and age between 45 and 60 years with a personal or family history of autoimmune disorders suggests primary biliary cholangitis (PBC). Male sex and age between 40 and 50 years with a history of inflammatory bowel disease (typically ulcerative colitis, but possibly Crohn's colitis) suggests primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC).

Ethnicity

May be useful in determining the underlying aetiology. Gaucher's disease and Niemann-Pick disease (type C) are more common among people of Ashkenazi Jewish descent. Patients with Felty syndrome (rheumatoid arthritis, splenomegaly, and neutropenia) often have white ancestry. People affected with sickle cell anaemia often have black ancestry, while Mediterranean or Southeast Asian ancestry suggests thalassaemia.

Past medical history and family history

A family history of haemochromatosis along with a personal history of arthralgias and diabetes suggests haemochromatosis.

Obesity along with a history of insulin resistance or diabetes, hyperlipidaemia and/or hypertension (metabolic syndrome), rapid weight loss, or total parenteral nutrition suggests hepatic steatosis.

A personal or family history of thrombophilia, paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria (PNH), or myeloproliferative disorders can precede Budd-Chiari syndrome, whereas a history of PNH or antiphospholipid syndrome may suggest portal vein thrombosis.

A history of pancreatitis may suggest splenic vein thrombosis.

A personal or family history of haemoglobinopathy suggests thalassaemia or sickle cell disease.

A personal or family history of lysosomal storage disease suggests Gaucher's or Niemann-Pick disease.

Patients with acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) may present with a history of haematological disease or genetic disorder such as chromosomal fragility and/or bone marrow failure disorders or chromosomal trisomies.

People with Felty syndrome often have a personal (>10 years) and family history of rheumatoid arthritis.

Travel history

A history of recent travel should be sought, particularly travel to malaria- and/or dengue-endemic regions. Residence in endemic areas (e.g., for hepatitis B infection) should also be excluded.

Past and current medications

Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor may be associated with splenic enlargement or, rarely, rupture.

High-dose chemotherapy can lead to Budd-Chiari syndrome.

Prior or current treatment with oral contraceptives raises the possibility of portal vein thrombosis.

Patients with AML or ALL may have a history of chemotherapy or exposure to radiation or benzene.

Social history

Alcohol misuse suggests the possibility of chronic liver disease.

History of intravenous drug abuse may suggest chronic hepatitis B or C infection, or infective endocarditis.

Malignancies may occur as a result of exposure to environmental toxins or pollutants (including smoking).

Trauma or hospitalisation

Splenomegaly due to splenic rupture or subcapsular haemorrhage, although rare, may occur following abdominal trauma or the use of iatrogenic foreign material (e.g., nasogastric tubes).

Intravenous line infections may be a source of infective endocarditis or splenic abscess. These may also occur as a result of recent urinary, pulmonary, or soft-tissue infection.

Other important factors

Presence of abnormal bleeding: bleeding from the nose and gums may occur in Waldenström's macroglobulinaemia, AML, or ALL.[11][12]

Respiratory symptoms: pharyngitis is typical of EBV infection. Cough and dyspnoea occur in sarcoidosis. Amyloidosis may present with dyspnoea in addition to fatigue. Adult T-cell leukaemia-lymphoma can present with respiratory symptoms caused by pulmonary infiltrates.[14] Aggressive B-cell lymphomas may present with pleural effusions.

Skin and hair symptoms: alopecia may occur in SLE. Skin rashes or masses may occur in AML. Skin nodules may occur in NHL. Patients with SLE commonly present with a photosensitive rash. T-cell prolymphocytic leukaemia may present with erythematous or papular skin lesions.[13]

Bowel function: steatorrhoea occurs in late PBC and PSC. Diarrhoea can occur in amyloidosis.

Musculoskeletal symptoms: bone pain may occur in AML, sickle cell disease (episodic), and Gaucher's disease. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis may present with joint deformities; history of bilateral, symmetrical pain, and swelling of the small joints of the hands and feet (>6 weeks); and morning stiffness. Arthralgia (involving knees, ankles, elbows, and wrists) is a common symptom of sarcoidosis and SLE.

History of bruising, petechiae, or purpura: any haematological condition that results in thrombocytopenia can present with bruising or bleeding. This includes NHL, Hodgkin's lymphoma, and acute and chronic leukaemias.

Neurological symptoms: may be features of high-grade NHL, Waldenström's macroglobulinaemia (headache and dizziness), or essential thrombocytosis (headache and painful burning in palms or soles [erythromelalgia]).

History of recent dental work or blood transfusions: may suggest infective endocarditis or hepatitis C infection, respectively.

Presence of jaundice: jaundice is a typical finding of late-stage chronic liver disease (e.g., due to hepatic steatosis, PBC, PSC). Lifelong jaundice is typical of inherent red blood cell disorders.

Physical examination

Abdominal examination

Palpation of an enlarged spleen is best accomplished by having the patient relax the abdominal wall. There should be mild flexion of the neck, the arms should be still at the sides (not over the head), and the knees should be flexed with the feet flat on the examining table. The examiner should stand at the patient's right and should start low in the mid abdomen and work upwards towards the left costal margin. Starting too high in the left upper abdomen might result in missing the edge of a massively enlarged spleen. Indeed, spleens can become so large as to occupy most of the abdomen. The higher edge can be very far to the right of the midline, and the lower edge may not be palpated because it is located in the pelvis.

Isolated splenomegaly (as opposed to hepatosplenomegaly) suggests chronic liver disease. The liver is usually shrunken in cirrhosis with secondary splenomegaly. Accompanying stigmata of chronic or end-stage liver disease of any aetiology include spider telangiectasias, ascites, palmar erythema, jaundice, or encephalopathy.

Hepatomegaly with an ill-defined soft edge may occur in CML; hepatomegaly is not a prominent feature of hairy cell leukaemia but can be observed. However, in late stages of hairy cell leukaemia, pain and fever may be accompanied by perisplenic fluid or splenic rupture.

Mild-to-severe splenomegaly and epigastric tenderness characterise portal vein thrombosis. LUQ tenderness and features of pancreatitis (tachycardia and hypotension in severe cases; discoloration around the umbilicus [positive Cullen sign] or flanks [positive Grey-Turner sign] in cases of haemorrhagic pancreatitis) suggest splenic vein thrombosis. Onset of splenomegaly can be rapid and painful. A classic triad of abdominal pain (especially RUQ), ascites, and hepatomegaly characterises Budd-Chiari syndrome.

Usually, splenic involvement by Hodgkin's disease is focal and multicentric, and it may or may not lead to palpable splenomegaly. However, if diagnosed late, the spleen can become quite enlarged. More unusual presentations of Hodgkin's disease are characterised by splenomegaly (splenectomy may be necessary for diagnosis) and are most often found in patients >60 years of age.[48] Hepatosplenomegaly can be seen in high-grade NHL.

Features found on general examination can provide important diagnostic clues. Acute signs such as tachypnoea, tachycardia, and hypotension characterise sepsis with splenic abscesses or splenic rupture. Following abdominal examination, physical examination should focus on the following:

Skin

The presence of pallor indicates anaemia and is a common finding associated with many of the causes of splenomegaly (e.g., leukaemias). Purpura and petechiae suggest thrombocytopenia, as in sequestration syndromes or haematological conditions. Periorbital purpura strongly suggests amyloidosis. Plethora is seen in polycythaemia vera. Skin infiltration and masses may be seen in AML, ALL, or some T-cell lymphomas; cutaneous ulcers (Sweet syndrome) or pyoderma gangrenosum are found in AML. Skin and mucosal bleeding are seen in Waldenström's macroglobulinaemia or essential thrombocytosis.[11][12] Roth spots or Janeway lesions suggest endocarditis.

Jaundice is found in Budd-Chiari syndrome and haemolytic anaemias and may occur in NHL and late-stage chronic liver disease. Cutaneous infection may be evident on clinical examination and can occur in leukaemias. Erythema nodosum and lupus pernio may be seen in sarcoidosis. Xanthelasma is found early in PBC, whereas skin thinning and muscle mass loss occur late.

Lymph nodes

Lymphadenopathy should be assessed and may suggest reactive processes such as autoimmune disorders (rheumatoid arthritis, Felty syndrome, SLE, sarcoidosis) but is more typical of lymphomas and leukaemias (less prominently in hairy cell than in other types of leukaemia). Posterior cervical adenopathy is seen with EBV infection. Generalised lymphadenopathy occurs with EBV infection in immunocompromised people.

Ears/nose/throat

Mucosal bleeding may be seen in Waldenström's macroglobulinaemia.[12] Pharyngitis occurs with EBV infection. Macroglossia, jugular venous distension, or periorbital oedema suggest amyloidosis. Frontal bossing maxillary expansion is seen with thalassaemias.

Cardiac examination

New or changing murmurs suggest endocarditis.

Genitourinary/reproductive

Testicular masses may be found in acute leukaemia or lymphomas.

Extremities

Digital ischaemia or gangrene and/or thrombosis suggest essential thrombocytosis.

Joint deformities are found in rheumatoid arthritis, SLE, and Felty syndrome.

Lower extremity oedema may be seen in amyloidosis.

Neurological

Abnormal neurological examination may be observed in essential thrombocytosis, NHL, or Waldenström's macroglobulinaemia.[11][12]

Neurological features include signs associated with hyperviscosity, including dizziness and visual changes due to retinal haemorrhage.[12][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Classic periorbital purpuraFrom the collection of Dr Morie A. Gertz; used with permission [Citation ends].

Laboratory testing

Initial testing in the work-up of splenomegaly should include a comprehensive metabolic panel to assess liver function; full blood count with differential, review of the peripheral blood smear, and reticulocyte count (especially when the patient is anaemic); and blood cultures (when the patient is febrile).

Additional investigations should be based on clinical and/or initial laboratory findings.

The presence of indirect hyperbilirubinaemia on liver function tests suggests haemolysis. Haemoglobin electrophoresis (sickle cell disease, beta-thalassaemia), Coombs testing (positive: autoimmune haemolysis and cold agglutinin disease; negative: hereditary spherocytosis), red cell enzyme testing (as in glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency), or osmotic fragility testing (as in hereditary spherocytosis) may help determine the aetiology.

Lymphocytosis on peripheral smear accompanied by immature or abnormal lymphocytes should prompt flow cytometry for lymphoproliferative profile. This can help diagnose chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, hairy cell leukaemia, and several of the peripheralised lymphomas (such as splenic marginal zone lymphoma or Sezary cells in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma).

Erythropoietin levels may be performed when considering a diagnosis of polycythaemia vera; levels can be normal but are usually low.

Coagulation tests can be a marker of liver synthetic dysfunction and are therefore useful in suspected alcoholic or chronic liver disease, disseminated intravascular coagulation in AML, fulminant presentations of Budd-Chiari syndrome, and SLE.

Serum lipase and amylase are useful when pancreatitis is suspected (suggests splenic vein thrombosis). Use serum lipase testing (if available) in preference to serum amylase.[49]

Serum LDH is an indicator of acute or chronic injury to tissues and should be considered in cases of suspected NHL or ALL/AML.

Serum erythrocyte sedimentation rate may be of use in Waldenström's macroglobulinaemia, although this is a non-specific marker of inflammation.

Serum iron studies are necessary if haemochromatosis is suspected.[50]

Calcium levels may be raised in certain T-cell lymphomas.[14]

Protein and immunofixation electrophoresis (serum, urine, or both) should be performed when considering a diagnosis of amyloidosis.

Alpha-globin gene deletion analysis supports the diagnosis of alpha-thalassaemia (usually abnormal) and should be considered in suspected cases.

Bone marrow analysis is necessary in cases of suspected myeloproliferative neoplasms, lymphomas, immunological diseases (haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis [HLH], sarcoidosis, SLE, Felty syndrome, amyloidosis), and lysosomal storage diseases (Gaucher's disease). In lysosomal storage diseases, quantification of the suspected enzyme deficiency, such as glucocerebrosidase deficiency in Gaucher's disease, may obviate the need for bone marrow testing. Bone marrow biopsy, along with lymph node biopsy, may obviate the need for splenectomy in Hodgkin's lymphoma. It may even reveal a benign splenic tumour.

Specialised tests can be useful in several instances:

Antimitochondrial antibodies are usually associated with PBC but can also be seen in PSC.

High levels of IgG and IgM can also be indicative of PSC. High-resolution serum electrophoresis with immunofixation confirms monoclonal IgM (kappa or lambda) secretion, required for diagnosis of Waldenström's macroglobulinaemia.[11][12]

The use of monoclonal antibodies for immunophenotyping and HLA typing may determine whether leukaemia is lymphoid or myeloid in origin (e.g., ALL).

Serology: approximately 30% of rheumatoid arthritis patients are rheumatoid factor (RF)-negative. Detection of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies may be positive in these patients.

Serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) may be elevated in sarcoidosis.

Natural killer (NK) cell activity and a soluble CD25 (soluble interleukin-2 receptor) may be used in the diagnosis of HLH.[29][33]

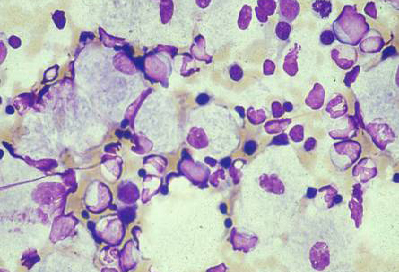

Infectious causes of splenomegaly can be confirmed by detection of the causal micro-organism in blood or other specimen cultures (malaria, dengue, endocarditis, splenic abscesses secondary to sepsis). Alternatively, serum agglutination tests or detection of specific antigens or antibodies can be used for EBV or hepatitis B or C. For hepatitis, quantification by polymerase chain reaction provides further information about viral burden.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Congo red stain blood vessel in a bone marrow biopsy demonstrating green birefringence pathognomonic of amyloidosisFrom the collection of Dr Morie A. Gertz; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bone marrow aspirate showing a typical Gaucher cellFrom the collection of Dr Atul B. Mehta; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bone marrow aspirate showing a typical Gaucher cellFrom the collection of Dr Atul B. Mehta; used with permission [Citation ends].

Imaging

Ultrasound

If splenomegaly is suspected, an ultrasound scan of the LUQ is a highly sensitive and specific non-invasive modality without radiation exposure.[51]

In select patients, especially those with portal vein or splenic vein thrombosis, Doppler ultrasonography may be necessary to determine whether veins draining the spleen are affected by clots (portal or splenic vein thrombosis).

Ultrasound elastography shows promise as a non-invasive tool sensitive to tissue stiffness.[52] It has been shown to differentiate between splenomegaly associated with cirrhosis and portal pathology, infection, myeloproliferative conditions, and normal spleens.[53][54]

Computed tomography (CT)

Despite the accessibility of ultrasound investigation, CT provides more detail and is the preferred modality when investigating the aetiology of splenomegaly (it is also more widely available than magnetic resonance imaging). CT scans can determine the degree of splenic enlargement and liver size, as well as heterogeneity or homogeneity. Numerous linear CT measurements, field, and volume coefficients have been proposed to best correlate with real splenic volume.[55][56][57][58]

Abdominal CT adds diagnostic value particularly in splenomegaly associated with alcohol misuse, hepatic steatosis, myelofibrosis, and subcapsular haematoma. Upper abdominal CT scans may show multiple tumours in the spleen that have metastasised from other primary tumour sites, particularly colon and breast cancer. Unsuspected lymphadenopathy in the retroperitoneum or mesentery may be detected, as well as mediastinal adenopathy on CT of the chest. Furthermore, CT scans can detect a splenic abscess causing LUQ pain in a patient with endocarditis.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Sometimes helpful, especially in cases of portal vein thrombosis with cavernous transformation. Various approaches to provide detailed computer-generated anatomical and pathological information based on clinical MRI scans are currently under investigation.[59][60] Usually, however, MRI confirms CT findings of the liver rather than the spleen, especially liver haemangiomas. An abnormal liver MRI pattern may also indicate iron overload in haemochromatosis.[50] Bone imaging reveals distinctive changes, such as the 'Erlenmeyer flask' sign in the distal femurs (Gaucher's disease).

Positron emission tomography (PET)

Can help to determine the metabolic activity of cells in the spleen, though does not necessarily distinguish between malignant and reactive changes. PET scans can be of particular value in diagnosing and staging Hodgkin's lymphoma and NHL.

Endoscopy

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy can detect oesophageal varices in splenomegaly secondary to alcohol misuse or other chronic liver disease.

Additional testing

Specific additional tests may be required depending on clinical findings and laboratory results.

Miscellaneous tests

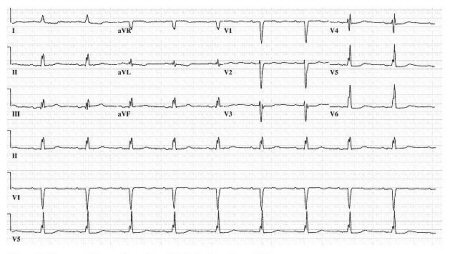

ECG may detect cardiac involvement in sarcoidosis or endocarditis.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: ECG of a patient with infective endocarditis. Note the first-degree AV block, non-specific intraventricular conduction delay, and non-specific ST-T wave abnormalitiesFrom the collection of the Mayo Clinic Rochester, MN; used with permission [Citation ends].

In cases of amyloidosis, abdominal fat pad aspiration may be positive for amyloid and can therefore support the diagnosis.

JAK2 mutation analysis can be useful in suspected cases of polycythaemia vera (confirms diagnosis), Budd-Chiari syndrome (positive with underlying myeloproliferative disorder), and essential thrombocytosis (present in approximately 50% of cases).[61][62][63][64]

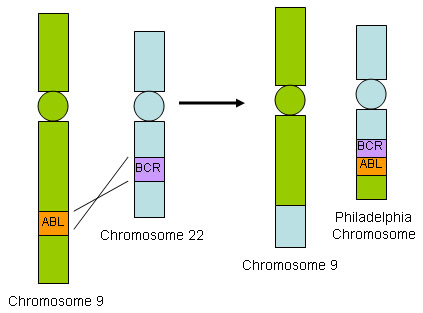

Gene tests may confirm the diagnosis of CML (BCR-ABL gene rearrangement positivity) and haemochromatosis (C282Y mutation homozygosity).

Glucocerebrosidase activity should be determined in suspected Gaucher's disease.

Sphingomyelinase assay can be used to assess Niemann-Pick disease.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: BCR-ABL1 translocationFrom the collection of Dr Han Myint; used with permission [Citation ends].

Biopsy

Lymph node biopsy is necessary for diagnosis of lymphoma or sarcoidosis.

Lung or skin biopsy can be valuable in sarcoidosis and should be considered.

Liver biopsy can add value to the diagnosis of the underlying cause, and to the management of splenomegaly secondary to alcohol-induced liver disease, hepatic steatosis, PSC, or haemochromatosis.

Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of the spleen may expose the patient to risk of splenic rupture. However, it may be diagnostic and avoid the need for splenectomy in highly selected cases: for example, low-grade NHL exhibiting usually small lesions or diffuse splenic involvement, or Hodgkin's lymphoma. It should be performed only by an experienced interventional radiologist, with surgical support in case of splenic laceration or rupture.

Diagnostic splenectomy

In some instances, splenectomy may be the only way to diagnose isolated splenic involvement (Hodgkin's lymphoma if lymph node and bone marrow biopsies inconclusive, primary splenic malignancies).

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer