Aetiology

The differential diagnosis of lymphadenopathy is broad and can be considered under the following categories (mnemonic MIAMI):[1]

Malignancies

Infections

Autoimmune disorders

Miscellaneous/unusual conditions

Iatrogenic causes.

Malignancy

In patients presenting with lymphadenopathy, concern for malignancy increases with age.[2] Cancers are identified in approximately 14% of patients who present with unexplained lymphadenopathy.[3] Among patients aged >65 years who present with enlarged lymph nodes, the risk of cancer is 28% within 1 year, rising to 42% within 10 years.[2]

A careful history and physical examination can provide clues to the possibility of an underlying malignancy.

Haematological malignancies such as Hodgkin's and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma often present with constitutional symptoms (B symptoms), which include fever (>38ºC), drenching night sweats, and unintentional weight loss (loss of >10 % of body weight over the past six months). Non-Hodgkin's lymphomas (NHL) have a greater predilection to disseminate to extranodal locations. Nearly one third of NHL cases arise in extranodal locations.[4]

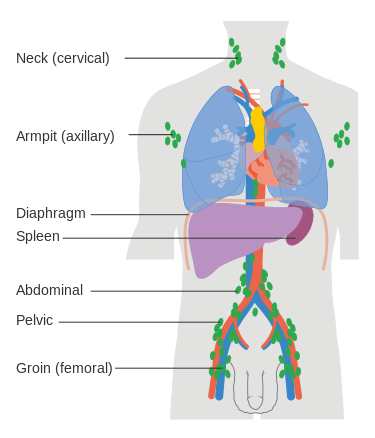

History of a prior cancer should prompt an evaluation for possible recurrent cancer or metastatic disease.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Diagram showing the lymph node groups most commonly affected by Hodgkin’s lymphomaCancer Research UK [Citation ends]. Supraclavicular nodes are more likely to be associated with cancer than enlarged nodes at other sites.[5]

Supraclavicular nodes are more likely to be associated with cancer than enlarged nodes at other sites.[5]

Infection

Infection is a common cause of lymphadenopathy.

On evaluation there may be localising signs or symptoms to indicate the presence of infection including upper respiratory symptoms (such as sore throat or rhinorrhoea), fever, skin ulceration, or recent insect bites. Pertinent aspects of the history include evaluating for recent travel (e.g., to southwest US, India, Asia, South America, West Africa), animal contact (e.g., cats), consumption of undercooked meat, high-risk sexual behaviour, intravenous drug use, or recent transfusion.

Viral, bacterial, fungal, protozoal, or parasitic infections can cause lymphadenopathy. Examples include:

Viral: infectious mononucleosis (Epstein-Barr virus), coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), cytomegalovirus, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, adenovirus, herpes zoster, herpes simplex, HIV, human T-lymphotropic virus 1, mumps, measles, rubella, mpox

Bacterial: staphylococcal and streptococcal infections (particularly pharyngitis), cat scratch disease, tuberculosis, atypical mycobacteria (such as mycobacterium avium-intracellulare), primary and secondary syphilis, tularaemia, brucellosis, chancroid, leptospirosis, chlamydia (lymphogranuloma venereum), Rocky Mountain spotted fever

Fungal: histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, cryptococcosis

Parasitic: toxoplasmosis, leishmaniasis

Mycobacterial: granulomatous lymphadenopathy can be associated with mycobacterial infections, including Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mycobacterium leprae, and atypical mycobacterial infections such as Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bilateral hilar adenopathyFrom the collection of Dr M.P. Muthiah; used with permission [Citation ends].

Autoimmune disorder

Lymphadenopathy in the presence of arthralgias, myalgias, morning stiffness, or rash should raise a concern for the presence of an autoimmune condition:

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE): lymphadenopathy may be a presenting feature of SLE or indicative of active disease, but it is not a diagnostic criterion[6]

Rheumatoid arthritis

Dermatomyositis

Sjogren syndrome.

Miscellaneous/unusual

Lymphadenopathy can be a presenting feature of a number of rare systemic diseases. These conditions often present with systemic symptoms including fever, night sweats, unintentional weight loss, and hepatosplenomegaly.[7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14] Biopsy is usually required for diagnosis. Examples include:

Sarcoidosis: usually involves the lung (90%) and may also present with skin signs (in 25% of people) and fatigue.[15][16] Peripheral lymphadenopathy is present in approximately 20% of patients.[17] Initial presenting symptoms include cough, dyspnoea, chest pain, fatigue, fever, and weight loss

Silicosis

Castleman disease (lymphoproliferative disorders characterised by lymph node enlargement)

Inflammatory pseudotumour

Progressive transformation of germinal centres

Rosai-Dorfman disease (sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy)

Kawasaki disease

IgG4-related disease

Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease.

Iatrogenic cause

The following hypersensitivity syndromes may be associated with reactive lymphadenopathy:

Serum sickness

Drug sensitivity

Vaccination-related

Graft-versus-host disease.

Drug-associated lymphadenopathy may occur acutely or delayed (weeks and months after initiation of the drug). Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptom (DRESS) is a severe adverse drug-induced reaction in which patients present with lymphadenopathy, skin rash, fever, hypereosinophilia, and deranged liver function tests.[18] Medications that can cause lymphadenopathy include:[19][20]

Allopurinol

Atenolol

Captopril

Carbamazepine

Hydralazine

Penicillins

Phenytoin

Quinidine

Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole

Terbinafine.

COVID-19 vaccination can result in lymphadenopathy on the ipsilateral side of injection, and is associated with a higher incidence of axillary lymphadenopathy on breast MRI and mammography.[21][22][23]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer