Approach

The diagnosis of MNM may be suspected from a clinical history, with patients typically presenting with painful, acute to sub-acute sensory and motor deficits that may start with involvement of a single nerve or multiple nerves, concurrently or in succession, progressing eventually to MNM as more nerves are cumulatively affected over time. Deficits may evolve quickly over days to form a confluent or overlapping pattern. Any nerve may be affected, although initial involvement of one of the branches of the sciatic nerve is the most common presentation.[1] Patients without pain, with greater proximal than distal weakness, or with purely motor involvement are unlikely to have a vasculitic neuropathy.[1]

History

Clinical history can be complicated, as there are so many potential aetiologies. Systemic vasculitis is more likely if symptoms from other organ systems (joint swelling, abdominal pain, pulmonary symptoms, Raynaud’s phenomenon, nasal or oral inflammation, or skin lesions) or systemic inflammation (e.g., fever, night sweats, anorexia, or weight loss) are present. These symptoms are rare in non-systemic vasculitic neuropathy. A history of weight loss, fatigue, myalgia, or arthralgia can indicate systemic or non-systemic vasculitis.[1][23] A patient may also present with isolated MNM without any history of symptoms to suggest a systemic illness.[45]

Physical examination

This is directed towards 2 goals:

Defining the pattern of peripheral nerve involvement and confirming the clinical suspicion that MNM is present

Eliciting signs of involvement of other organ systems that may give clues to the underlying aetiology of the disorder.

To search for signs of MNM aetiology a physical examination should investigate: vital signs; the eyes, mouth, nose, throat, skin, and nerves; joints, abdominal area, and genital area.

When examining eyes, look for dry conjunctivae (indicating sarcoidosis, Sjogren syndrome, or systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE]).

During a neck/face examination, search for an enlarged parotid, which particularly suggests sarcoidosis or amyloidosis, while lesions of the nasalpharynx indicate granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly known as Wegener's granulomatosis), and painful, shallow oral and nasal ulcers suggest SLE.

A pulmonary examination detecting wheezing in a patient with eosinophilia suggests eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly known as Churg-Strauss syndrome). Dry rales may be heard in patients with sarcoidosis.

Examination of the skin is important (e.g., palpable purpura indicate granulomatosis with polyangiitis or eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, malar 'butterfly' rash suggests SLE). Skin lesions in leprosy include hypo- or dyspigmented anaesthetic patches. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Borderline tuberculoid leprosy showing depigmented anesthetic skin patchesFrom the personal collection of Professor Ashok Verma; used with permission [Citation ends].

Examining the abdomen, genitals, and joints may be diagnostic: an enlarged spleen suggests rheumatoid vasculitis; painful genital aphthous ulcerations indicate Behcet syndrome; and joint swellings or mild warmth suggest systemic disorders, including seropositive invasive rheumatoid arthritis or SLE.

Search for nerves that are palpably enlarged (i.e., superficial radial nerve, auricular nerve) in cases of hereditary demyelinating neuropathies, or, if also hardened and tender, suggesting leprosy.

Initial investigations

The most important evaluations in a patient with suspected MNM are the following:

Laboratory studies including:[46]

Renal function tests (serum creatinine) and urinalysis: renal manifestations are common in granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly known as Wegener's granulomatosis), microscopic polyarteritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus

Fasting blood glucose: diabetes mellitus may cause either MNM or a diabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy

Liver function tests

FBC with differential: patients with vasculitic neuropathy may demonstrate anaemia, eosinophilia, leukocytosis, or thrombocytosis

Inflammatory markers: erythrocyte sedimentation rate and/or C-reactive protein may be elevated in patients with vasculitic neuropathy

Initial serological tests: cryoglobulin, serum complement, angiotensin-converting enzyme, rheumatoid factor, and antibodies associated with systemic vasculitis (antinuclear antibodies [ANA], anti-double-stranded DNA, anti-Sjogren syndrome-related antigen A [SSA]/SSB antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies [ANCA])

Serology for hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV.

Chest x-ray or chest computed tomography (CT). Abnormal findings are consistent with a systemic vasculitis, sarcoidosis, or neoplasm. X-ray is usually the first imaging investigation, with the more sensitive CT used as follow-up.

Electrodiagnostic (electromyographic) studies. An electromyogram (EMG) should be performed for every patient presenting with clinical MNM. The clinically affected limb or limbs should be specified, with attention to the specific nerves that appear to be affected. Diagnostic sensitivity is high if the clinically involved nerves are compared with unaffected nerves. Typical findings in a primary or secondary vasculitis leading to MNM are of an axonal, active, asymmetrical or multifocal, distally predominant sensorimotor neuropathy.

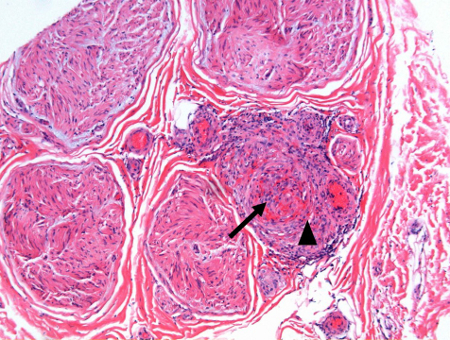

Peripheral nerve or nerve/muscle biopsy. Nerve or muscle/nerve biopsy should be considered for every patient with clinical MNM. Non-systemic vasculitic neuropathy can only be definitively diagnosed with a nerve biopsy.[23] Biopsy is typically performed on a pure sensory nerve without motor supply (e.g., sural, distal superficial peroneal, posterior cutaneous nerve of the thigh, or superficial radial). EMG should be used to guide the biopsy site. Histological features of necrotising vasculitis are generally found in the clinical syndrome of vasculitic MNM. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Medium-size artery and arterioles in epi- perineurium of sural nerve showing transmural dense mixed cell infiltrates, fibrinoid necrosis and luminal occlusion (arrow) in a case of polyarteritis nodosa. Note that the muscularis layer is interrupted and destroyed by the inflammatory infiltrate (arrowhead). Paraffin section; Hematoxylin and EosinFrom the personal collection of Professor Sakir Humayun Gultekin, MD, FCAP; used with permission [Citation ends].

However, segmental nerve involvement and skip areas may fail to show vasculitis in the limited biopsy tissue.

However, segmental nerve involvement and skip areas may fail to show vasculitis in the limited biopsy tissue.

Referral to a neuromuscular neurological consultant should be considered before performing the electrodiagnostic studies and biopsy of nerve/muscle. In addition, referral to rheumatologist should be considered if a systemic vasculitis is suspected.

See Investigations.

Subsequent investigations

In selected patients, other evaluations may be helpful to determine MNM aetiology. These include skin biopsy of vasculitic lesions (e.g., palpable purpura, erythema, petechiae, nodules, maculopapules, and livedo reticularis; useful for determining a variety of vasculitic aetiologies), and a lip biopsy (minor salivary gland biopsy), which is diagnostic for Sjogren syndrome. Arteriography of the visceral and renal circulation may be helpful in the diagnosis of classic polyarteritis nodosa.[8]

In appropriate clinical settings, anti-topoisomerase I (anti-Scl 70), anti-Smith, anti-centromere (ACA), anti-Hu, and Lyme serology may indicate specific autoimmune, neoplastic, or infectious aetiology. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis may suggest Lyme polyradiculopathy, cytomegalovirus radiculomyelopathy in HIV disease, or neurosarcoidosis.

If no aetiology for MNM is identified with initial tests, imaging for malignancy (including CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis) and anti-Hu antibodies (associated with small-cell lung cancer or paraneoplastic MNM) should be ordered. Positron emission tomography scan may be considered if CT results are negative and a paraneoplastic MNM is suspected.

There is not enough evidence that magnetic resonance angiography is sensitive enough for evaluating a patient with suspected MNM and medium-, small-, or variable-size vessel vasculitis (primary non-systemic vasculitic neuropathy).[23] Conventional catheter angiography is required to document small and medium caliber vessel involvement in vasculitis. Abnormal angiography findings suggestive of a systemic vasculitis such as polyarteritis nodosa may include microaneurysms, 'beading' as a result of sequential areas of arterial narrowing and dilation, and stenosis.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer