Approach

Patients in whom there is a clinical suspicion of steatorrhoea should first have the diagnosis confirmed by stool testing for fat. If confirmed, a thorough history and physical examination should identify those with possible pancreatic disease or intestinal disease that can cause steatorrhoea. Subsequent blood and stool tests can narrow the differential diagnosis and guide further investigations.

History

Patients with steatorrhoea typically report fatty, bulky stools that are difficult to flush away. This occurs only after fat-containing meals and therefore may not be a daily symptom. As steatorrhoea occurs after meals, it typically happens 2 to 3 times a day in individuals with a normal lipid-content diet. Weight loss and anorexia may also develop over time due to malnutrition.

As any disease causing diarrhoea may manifest as steatorrhoea, there are a few clinical symptoms that may differentiate between the many underlying aetiologies.

Abdominal pain: usually epigastric, is common in patients with chronic pancreatitis. It can be constant or intermittent in nature, and tends to improve with time, as the pancreas becomes 'burnt out'.[29] It is at this stage that steatorrhoea may appear as a manifestation of exocrine insufficiency.

Jaundice: common in patients with cholestasis, but is infrequent in patients with cirrhosis until late in the disease process.

Pruritus: characteristic of primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), although most patients with PBC are initially asymptomatic.

Coeliac disease, giardiasis, and bacterial overgrowth: may cause bloating, flatulence, and crampy abdominal pains in addition to steatorrhoea. It is increasingly recognised that coeliac disease has more subtle presentation features such as unexplained anaemia, weight loss, or osteoporosis in the absence of diarrhoea.[30][31][32]

Crohn's disease: typically presents with lower abdominal pain in young adults, with or without diarrhoea. Extra-intestinal symptoms such as joint pain, uveitis, and fatigue occur in up to 10% of patients.[33] Crohn's disease may be preceded by a label of irritable bowel syndrome in about 25% of patients.[34]

Increased appetite, combined with weight loss, heat intolerance, and hair loss: suggests hyperthyroidism.

The following features should be enquired about in a patient's medical history.

Prior surgical resection of the stomach, pancreas (e.g., Whipple's operation, pylorus-preserving pancreatectomy, or total pancreatectomy), or small bowel (e.g., ileal resection, jejunal by-pass, gastrectomy).

Severe acute necrotising pancreatitis or recurrent episodes of acute pancreatitis. Some patients with chronic pancreatitis have no prior history of clinical pancreatitis episodes (painless pancreatitis).

Head of the pancreas cancer; tumours in this region can directly obstruct the pancreatic ducts and may be associated with exocrine pancreatic insufficiency.[35]

History of malabsorptive conditions (e.g., coeliac disease, giardiasis, Whipple's disease, HIV/AIDS, lymphoma, gastrointestinal amyloidosis).

Use of tetrahydrolipstatin (orlistat), meclofenamate sodium, or olestra-containing products (a fat substitute ingredient). The availability of lipase inhibitors over the counter in the US has widened their usage in that country and led to the possibility of patients not recognising their adverse effects.[36]

Alcohol dependence (a risk factor for cirrhosis and chronic pancreatitis).

Diabetes, which can occur in chronic pancreatitis.

Recurrent pulmonary/upper respiratory tract infections suggestive of cystic fibrosis gene mutations.

Physical examination

The physical examination should focus on signs of underlying conditions that can cause steatorrhoea. If possible, the stools should be examined to confirm steatorrhoea. Other pertinent features include the following.

General appearance of wasting/weight loss, such as temporal scalloping, interosseous wasting, and lack of subcutaneous fat. This occurs with chronic malabsorption, end-stage cirrhosis, and extensive small-bowel Crohn's disease.

Skin jaundice, suggesting biliary obstruction. Icterus first appears under the tongue, then in the sclera, then throughout the skin. Scratch marks on the skin suggest pruritus associated with PBC. Crohn's disease may present with erythema nodosum.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A patient's arms and hands show the presence of erythema nodosumCourtesy of CDC/ Margaret Renz; used with permission [Citation ends].

Hand changes such as nail clubbing can occur with cystic fibrosis and nail leukonychia due to hypoalbuminaemia from malabsorption. Telangiectasia and palmar erythema suggest underlying cirrhosis. Ecchymoses (bruising) may occur due to clotting abnormalities in the setting of cirrhosis or vitamin K deficiency.

Contraction or spasm of muscles may occur due to hypocalcaemia.

Fine tremor, goitre, exophthalmos, and tachycardia are associated with hyperthyroidism.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Lid retraction and mild proptosisCourtesy of Dr Vahab Fatourechi; used with permission [Citation ends].

Pulmonary signs such as dull lung bases and coarse crepitations occur when bronchiectasis develops in cystic fibrosis.

Abdominal signs of hepatomegaly or splenomegaly, and later ascites, indicate cirrhosis. Surgical scars from prior resections may suggest causes not elicited in the patient's history. Occasionally Crohn's disease can cause a lower abdominal mass, as can small-bowel lymphoma.

Investigations

Laboratory and radiological investigations should:

Confirm steatorrhoea

Determine type of steatorrhoea

Assess for conditions that cause fat malabsorption.

Although fatty stools have a characteristic appearance, excess faecal fat should be confirmed objectively. As fat malabsorption depends on an adequate dietary fat intake, patients who restrict the lipid composition of their diet, or are fasting, will not experience steatorrhoea, regardless of the cause. It is thus important that patients undergoing tests for faecal fat consume approximately 100 g of fat a day to ensure adequate assessment of lipid absorption.

Testing for faecal fat in patients with suspected steatorrhoea

Sudan stain of a random sample of homogenised stool (also known as qualitative faecal fat testing) is typically the initial test. Acetic acid and Sudan III stain are added to the stool sample, which is then heated and placed on a glass slide. The number and size of the fat globules per high-power field (hpf) is scored (normal ≤20/hpf, 1 to 4 micrometre in size; slightly increased >20/hpf, 1 to 8 micrometre in size; definitely increased >20/hpf, 6 to 75 micrometre in size).[37] A modification of this method reported a sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 95% in diagnosis of faecal fat when compared with chemical fat analysis.[38]

Steatocrit is a quantitative measure of fat as a proportion of a whole centrifuged homogenised stool sample.[39] A spot acid steatocrit level (normal <10%) has been reported as having a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 95% when compared with 72-hour quantitative fat analysis.[40]

72-hour fat chemical analysis (van de Kamer method) is considered the most accurate test for faecal fat quantification, although a 24-hour sample is more commonly obtained. Patients need to record a food diary to ensure adequate dietary fat was consumed during the test (100 g/day).[41] The normal output is <7 g of fat per 24-hour period (or <21 g of fat per 72-hour period).[42] It should be noted that any cause of large-volume diarrhoea can cause elevated (7 to 14 g/day) faecal fat levels despite an intact lipid absorption system, so mildly elevated levels should be interpreted with caution.[43] Faecal fat estimation is unpleasant and laborious, and is no longer performed in many laboratories.[44][45]

Most laboratories perform a random (spot) stool Sudan stain first. If positive in a patient on a normal diet, a 24-hour quantitative test should be performed. A negative test result makes steatorrhoea unlikely.[46]

The following investigations can help determine whether it is only fat that is being malabsorbed, or other nutrients also.

Pancreatic exocrine insufficiency can be screened for by measuring faecal elastase-1, a simple non-invasive test for pancreatic exocrine insufficiency. This enzyme is produced in the pancreas and is stable during intestinal transit, so faecal concentration of the enzyme correlates well with exocrine pancreas secretion.[47] A repeat faecal elastase-1 test should be considered if a watery stool sample is reported by the laboratory (can be falsely low due to dilution), or when no definite cause of pancreatic exocrine insufficiency is identified, to ensure correct diagnosis.[35]

More specialised tests for pancreatic exocrine insufficiency include aspiration of pancreatic contents after secretin or secretin-cholecystokinin administration, the 14C-triolein breath test, and the cholesteryl-[1-13C] octanoate breath test.[48][49]

Malabsorption of carbohydrates can be tested for using the D-xylose test (normal serum D-xylose concentration >1.33 mmol/L [20 mg/dL] 1 hour after an oral dose of D-xylose), and malabsorption of protein by testing for faecal alpha-1 antitrypsin excretion (normal <2.6 mg/g stool) or faecal chymotrypsin excretion (normal >6 U/g).[50]

Bile salt deficiency in the jejunum can be investigated with gamma camera scintigraphy after intake of oral 75Se-homocholic acid taurine (75Se-HCAT). This test determines the percentage re-absorption of bile acids and identifies impaired absorption (<10% retention).[51][52]

All patients with confirmed steatorrhoea should have a faecal elastase test, and if negative, a D-xylose and alpha-1 antitrypsin test. If these are all negative, then referral to a specialist centre to test for bile salt deficiency should be considered.

Guided by the findings of the history and examination, any of the following investigations may be appropriate in assessing a patient with steatorrhoea.

Laboratory

Faecal elastase-1 when investigating possible pancreatic exocrine insufficiency due to chronic pancreatitis. Serum IgG4 level may help exclude autoimmune pancreatitis.

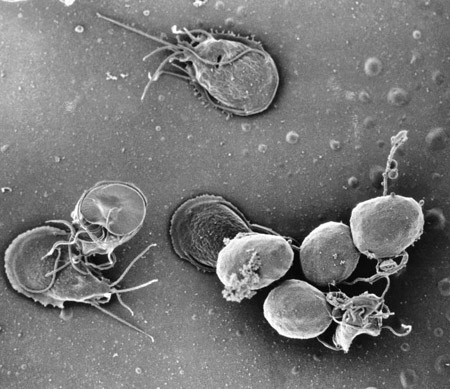

Stool microscopy and culture for ova, cysts, and parasites when investigating possible infection with Cryptosporidium, Giardia, microsporidia, Cyclosporidium, or Clostridium difficile. Enzyme immunoassay may be used as an alternative.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A scanning electron micrograph of an in vitro Giardia lamblia culture. The image shows trophozoites and a cluster of maturing cysts (bottom right)Courtesy of CDC/ Dr Stan Erlandsen; used with permission [Citation ends].

Direct serum bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, gamma-GT tests in patients with possible biliary obstruction.

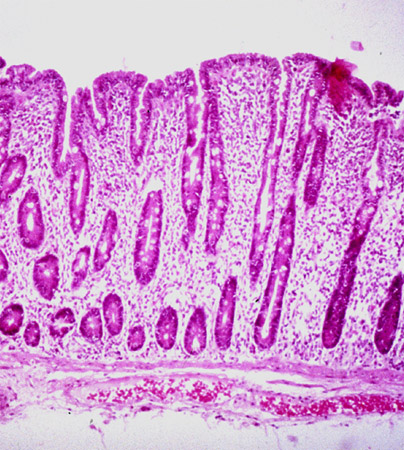

IgA tissue transglutaminase titre (tTG-IgA), serum total IgA level, IgG deamidated gliadin peptide (DGP-IgG) and IgG tissue transglutaminase (tTG-IgG) (performed in all patients with low IgA levels or IgA deficiency), and endomysial antibody should be considered in a patient with suspected coeliac disease.[16][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Histological image demonstrating small-intestinal villous atrophy and crypt hyperplasia in coeliac diseaseCourtesy of Dr Daniel A. Leffler; used with permission [Citation ends].

Inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) correlate closely with the activity of Crohn's disease.[53]

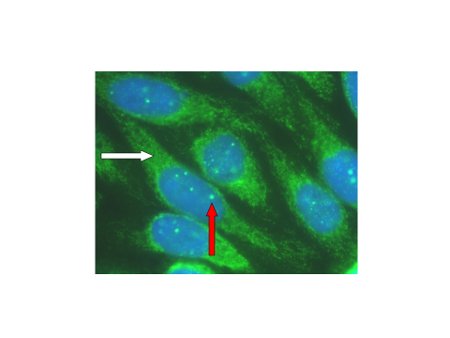

Serum anti-mitochondrial antibodies and alkaline phosphatase are the initial diagnostic tests when investigating primary biliary cholangitis (previously known as primary biliary cirrhosis). Liver biopsy may be needed to confirm the diagnosis.[54][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Characteristic auto-antibody patterns in primary biliary cholangitis. White arrow: anti-mitochondrial staining; red arrow: multiple nuclear dot ANA stainingCourtesy of DEJ Jones; used with permission [Citation ends].

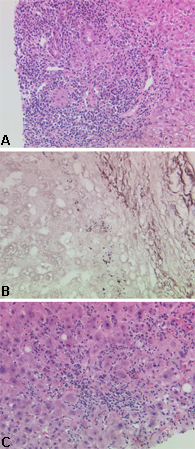

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Characteristic histological appearances of primary biliary cholangitis: (a) early stage disease; (b) advanced-stage disease; (c) disease with a significant inflammatory componentCourtesy of Professor Alastair Burt, Newcastle University; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Characteristic histological appearances of primary biliary cholangitis: (a) early stage disease; (b) advanced-stage disease; (c) disease with a significant inflammatory componentCourtesy of Professor Alastair Burt, Newcastle University; used with permission [Citation ends].

HIV antibody testing is required to confirm HIV infection.

Genetic testing, looking for transmembrane conductance regulator or trypsinogen gene mutation, when considering inherited diseases of the pancreas, such as cystic fibrosis.

Testing auto-antibodies, such as perinuclear-staining anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA), may aid in the diagnosis of primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Thyroid evaluation with thyroid-stimulating hormone, free thyroid hormones, and thyroid radioiodine uptake scan (scintigraphy) to assess for hyperthyroidism.

Imaging

Abdominal CT scan with oral and intravenous contrast to look for small-bowel lymphoma, Crohn's disease, or pancreatic abnormalities.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan demonstrating thickening of the terminal ileum in a patient with Crohn's disease exacerbationCourtesy of Drs Wissam Bleibel, Bishal Mainali, Chandrashekhar Thukral, and Mark A. Peppercorn; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan demonstrating thickening of the terminal ileum in a patient with Crohn's disease exacerbationCourtesy of Drs Wissam Bleibel, Bishal Mainali, Chandrashekhar Thukral, and Mark A. Peppercorn; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan demonstrating thickening of the terminal ileum in a patient with Crohn's disease exacerbationCourtesy of Drs Wissam Bleibel, Bishal Mainali, Chandrashekhar Thukral, and Mark A. Peppercorn; used with permission [Citation ends].

Endoscopic ultrasound of the pancreas may be used to investigate pancreatic abnormalities when CT scan is unavailable.

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP)/MRI to look for biliary disease or pancreatic duct disease. If relevant strictures are identified in the setting of alarm symptoms, endoscopic ultrasonography or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) should be carried out in order to obtain more imaging information and to take tissue specimens for cytological examination.[55][56] For extra-hepatic strictures, endoscopic ultrasound-guided tissue acquisition may be preferred over ERCP.[57][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Typical endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) findings in a patient with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC): multifocal strictures of the intra- and extrahepatic bile ductsCourtesy of Dr Kris Kowdley; used with permission [Citation ends].

Secretin-enhanced MRCP may be considered if cross-sectional imaging or endoscopic ultrasound is non-confirmatory and clinical suspicion of chronic pancreatitis remains high.[58]

Endoscopic

Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (OGD) and small-bowel biopsy if investigating a possible case of Whipple's disease.

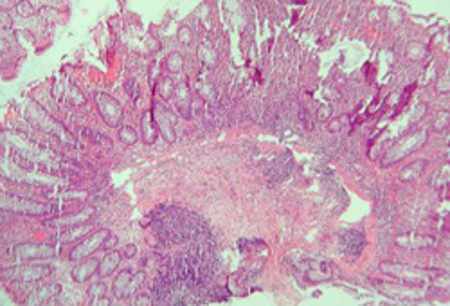

Colonoscopy and biopsy may be helpful when investigating Crohn's disease, microsporidia, cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection, and histoplasmosis, while colonoscopy/endoscopy and biopsy may be helpful when investigating lymphoma. Capsule biopsy is emerging as a promising test for diagnosing early lesions of Crohn's disease.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Significant inflammation in the colonic wall, widening of submucosa, and dense lymphoid aggregates in the submucosaCourtesy of Drs Wissam Bleibel, Bishal Mainali, Chandrashekhar Thukral, and Mark A. Peppercorn; used with permission [Citation ends].

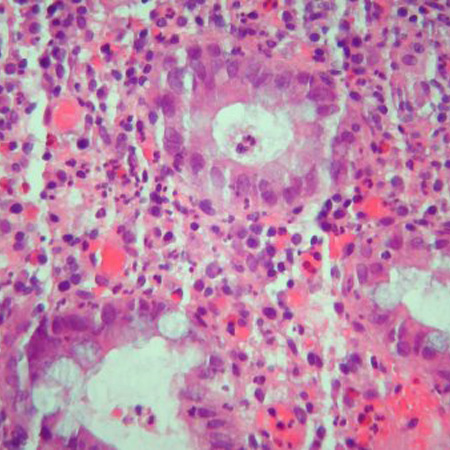

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cryptitis and crypt abscess with morphological distortion of the crypts accompanied by inflammation and abundant lymphatic and plasma cellsCourtesy of Drs Wissam Bleibel, Bishal Mainali, Chandrashekhar Thukral, and Mark A. Peppercorn; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cryptitis and crypt abscess with morphological distortion of the crypts accompanied by inflammation and abundant lymphatic and plasma cellsCourtesy of Drs Wissam Bleibel, Bishal Mainali, Chandrashekhar Thukral, and Mark A. Peppercorn; used with permission [Citation ends].

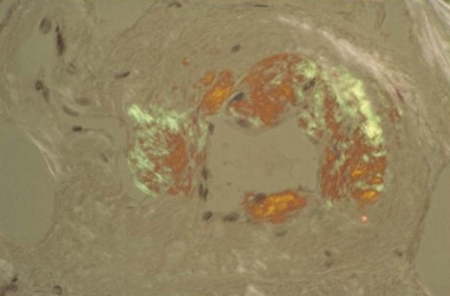

Deep rectal biopsy is necessary to confirm a diagnosis of suspected gastrointestinal amyloidosis.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Congo red stain blood vessel in a bone marrow biopsy demonstrating green birefringence pathognomonic of amyloidosisCourtesy of Morie A. Gertz, MD/Mayo Clinic; used with permission [Citation ends].

Other

Hydrogen breath test when assessing for bacterial overgrowth.[59]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer