Approach

The diagnosis of abusive head trauma requires that medical personnel be vigilant for signs of abuse when evaluating infants or children with signs of scalp, skull, or brain injury. Thorough history taking and a very careful medical examination are imperative. The presence of unexplained external head trauma, skull fracture, subdural bleeding, clinical signs of brain injury, and retinal haemorrhage or retinoschisis, is highly suggestive of abusive head trauma.

Hospital social work and child protection team staff should be involved as soon as the possibility of inflicted injury is apparent.[1][22]

Any underlying metabolic disorder, clinically significant bleeding disorder, or infection should be excluded. Medical evaluation may involve testing for osteogenesis imperfecta, congenital clotting abnormalities, or glutaric aciduria type I.[31][32][33][34]

History

The carer's history is generally inconsistent with the medical findings.

Carers may offer either no history of trauma or a history of minor trauma that in no way could lead to scalp or skull injury or the degree of brain injury that is present.[35] Typically, perpetrators have a period of time when they are alone with the infant, and they may describe an event that a child is developmentally incapable of (such as a 2-month-old infant crawling to the edge of a surface and falling). It is common for the history given by the perpetrators to change as they are interviewed by sequential medical providers.

There may also be a delay in seeking treatment; it is not uncommon for a carer who has injured an infant to call a non-offending parent at work and attempt other measures to wake up an infant before seeking emergency medical treatment.

Symptoms of apnoea, seizure, vomiting, and loss of muscle tone were all documented in a study of perpetrator confessions, with symptoms apparent immediately after shaking in 91% of cases.[12][14][16] Child maltreatment may be further suspected if a child has repeated life-threatening events, the onset is witnessed only by one parent or carer, and a medical explanation has not been identified.[22]

There may be an intercurrent illness or recent vaccinations leading to fever, which may make diagnosis more difficult, as the infant's symptoms of irritability or vomiting may be confused with viral infection or meningitis. Additionally, symptoms vary depending on the degree of injury, and milder injury may present with gradually developing symptoms.[1]

A significant number of infants have history or previous medical evaluations that in retrospect are likely to represent previous episodes of injury.[24] If medical providers do not have a high degree of suspicion, they may misdiagnose symptoms of mild injury as gastroenteritis, colic, meningitis, or pyloric stenosis. Radiologists who are not trained in paediatric radiology may misread subtle findings that are indicative of abusive trauma.

Some infants with mild injury may not be brought to medical attention and may recover on their own. These infants may present with an increasing head circumference noted by a primary care physician. Non-offending parents may be completely unaware that abuse is taking place. Infants may be brought to medical care for a non-related medical complaint such as respiratory distress, and have an evaluation that incidentally identifies signs of inflicted injury, such as rib fractures on a chest radiograph.

Abusive head trauma occurs in families from all socio-economic backgrounds; however, one study found that diagnosis is more likely to be missed in white children of married parents.[24]

Other points in the history that may suggest child maltreatment include known risk factors such as parental/carer drug or alcohol misuse, parental or carer mental illness, and a history of violent offending or previous child maltreatment within the family.[10][22]

Physical examination

Physical examination commonly does not reveal any external signs of injury. The fontanelle may be full or tense, and there may be a documented change in head circumference. Oral injuries are uncommon, but the finding of mucosal injury or torn labial or lingual frenulum is of concern.[36] Abusive long-bone fractures may be detected on physical examination; however, many abusive fractures such as the posterior rib fracture and classic metaphyseal lesion (corner fracture) usually have no overlying bruising or swelling.[35]

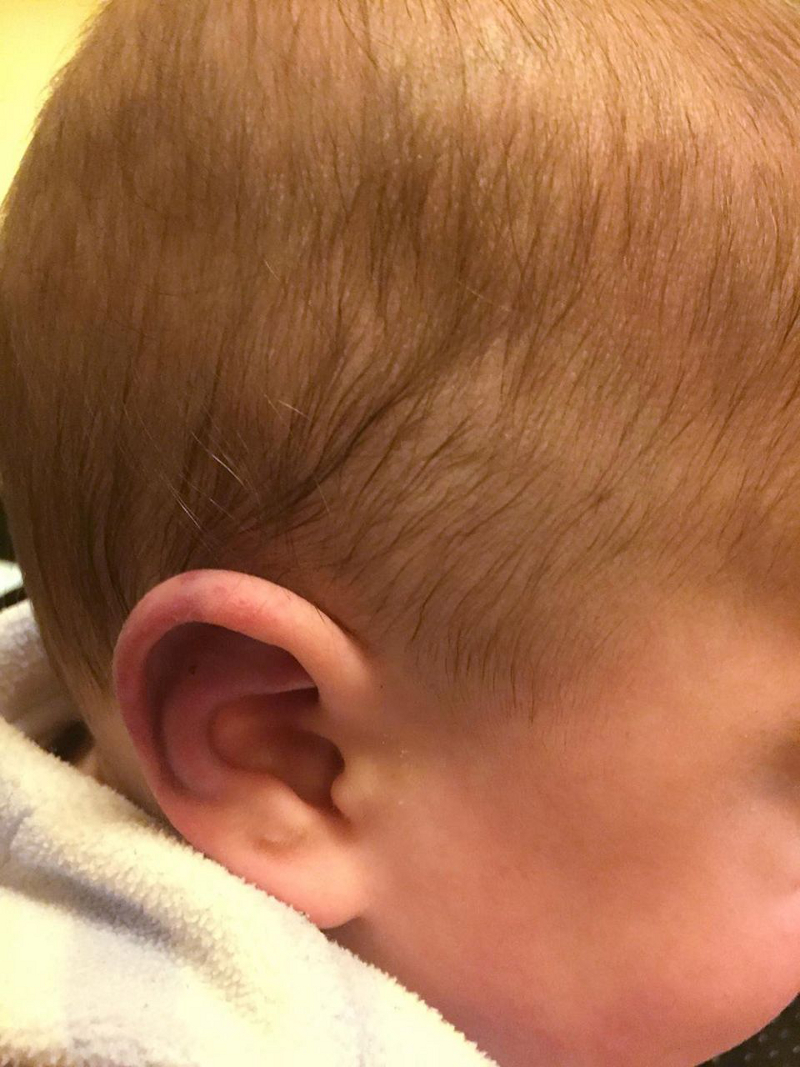

Skin findings including bites or bruising may be present. Bruising of the torso, ears and neck, or any bruising in a child younger than 4 months, should raise concern for inflicted injury.[37] Anogenital signs or symptoms without an appropriate explanation should raise the concern of child maltreatment.[22]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bruising on the ear of a 10-month-old infantReproduced with permission from Backhouse L et al. Unexplained bruising: a developing story. BMJ Case Rep. 2018 May 14;2018:bcr2017222793 [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Torn labial frenulum with associated bruising in a neonateReproduced with permission from Gurung H et al. Labial frenum tear from instrumental delivery. Arch Dis Child. 2015 Aug;100(8):773 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Torn labial frenulum with associated bruising in a neonateReproduced with permission from Gurung H et al. Labial frenum tear from instrumental delivery. Arch Dis Child. 2015 Aug;100(8):773 [Citation ends].

Neurological presentation

Varies depending on the degree of injury; however, some clinical signs of brain injury are usually present. Neurological signs may include irritability, vomiting, brisk or asymmetrical reflexes, poor muscle tone, seizures, or coma.

Paediatric Glasgow Coma Scale

The paediatric Glasgow Coma Scale comprises three assessments: eye, verbal, and motor responses. The lowest possible value is 3 (deep coma or death), while the highest is 15 (fully awake and aware person).

Best eye response (E):

No eye opening

Eye opening to pain

Eye opening to speech

Eyes opening spontaneously

Best verbal response (V):

No verbal response

Infant moans to pain

Infant cries to pain

Infant is irritable and continually cries

Infant coos or babbles (normal activity)

Best motor response (M):

No motor response

Extension to pain (decerebrate response)

Abnormal flexion to pain for an infant (decorticate response)

Infant withdraws from pain

Infant withdraws from touch

Infant moves spontaneously or purposefully

The use of the paediatric Glasgow Coma Scale, rather than the AVPU (alert, voice, pain, unresponsive) scale, is advised by the UK National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the evaluation of paediatric head injury.[38]

NICE suggests that child maltreatment is likely if a child has an intracranial injury in the absence of major confirmed accidental trauma or known medical cause, in one or more of the following circumstances:[22]

The explanation is absent or unsuitable

The child is aged under 3 years

There are also

Retinal haemorrhages or

Rib or long-bone fractures or

Other associated inflicted injuries

There are multiple subdural haemorrhages, with or without subarachnoid haemorrhage, with or without hypoxic damage to the brain.

Retinal examination

Retinal and vitreous haemorrhages and traumatic retinoschisis are characteristic of violent shaking leading to abusive head trauma.[1][39] Retinal haemorrhage can also be seen with crush injuries to the skull, although usually to a lesser degree.

Ophthalmology should be consulted to perform a dilated retinal examination if the child is clinically stable.[39] It may be necessary to delay this examination if the child's clinical status is guarded. Retinal haemorrhage can be transient: ophthalmological consultation should preferably take place within 24 hours after the child presents for medical care.[39]

Widespread, multi-layer retinal haemorrhages are believed to occur with abusive shaking when the vitreous humour, which is adherent to the retina, is set into motion, causing shearing forces on the retina and splitting of the layers of the retina. Retinal haemorrhage may be unilateral or bilateral. However, in 15% to 25% of cases there is no evidence of retinal haemorrhage.[13][40][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Retinal haemorrhages in abusive head trauma are usually widespread and multi-layered, as seen in this imageFrom the personal collection of Alice Newton, MD; used with permission [Citation ends].

Cranial imaging

Cranial imaging is indicated when there is a clear suspicion of inflicted traumatic brain injury and in cases where more general abuse is suspected.[41] In infants <6 months who have findings of other physical abuse injuries, head imaging should always be obtained.

Imaging should be performed as soon as possible, both for diagnosis and treatment of the patient, and for the protection of other children who are cared for in the same setting where abuse took place (e.g., siblings).

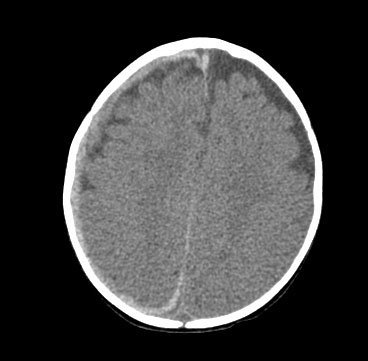

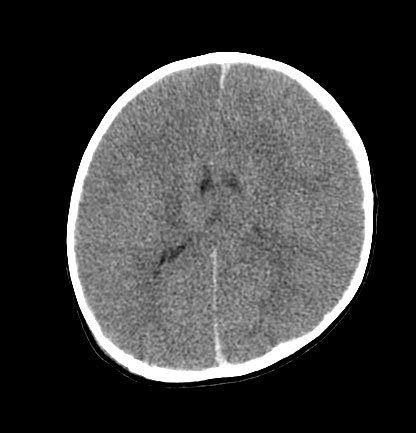

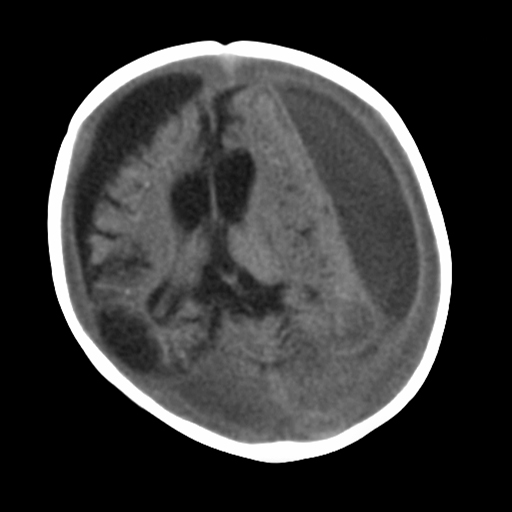

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain is usually the first study performed because of speed and availability. Further imaging with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is indicated if inflicted traumatic brain injury is diagnosed by CT or if there is a high suspicion of abusive head injury with a negative CT.[41][42] MRI may identify subdural collections, cortical contusions, ischaemia, intraparenchymal haemorrhage, and shearing injuries.[42]

Cranial ultrasound is not sensitive enough for routine diagnostic use.[42] In cases of unexplained increasing head circumference or in very unstable patients, cranial ultrasound can be helpful to detect subdural haemorrhage and to identify subarachnoid or subdural fluid collection. Cranial ultrasound, however, may not identify small subdural collections. High resolution ultrasound may be used to monitor lesions identified on CT or MRI.

In the UK, NICE advises performing a CT scan within 1 hour of identifying a number of risk factors, including any suspicion of non-accidental injury.[38] Depending on the presentation, a CT scan of the cervical spine or an MRI of the spine may also be required to exclude spinal injury.

A neurosurgical consult is generally required in most cases of inflicted brain injury, especially when there are signs or symptoms of raised intracranial pressure such as irritability, vomiting, and a tense fontanelle, or radiological evidence.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan revealing subdural haemorrhage extending over the right convexity and in the intrahemispheric region, as well as enlargement of the extra-axial fluid spacesFrom the personal collection of Alice Newton, MD; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT findings in fatal abusive head trauma often reveal significant brain oedema with loss of grey-white differentiation and effacement of the ventricles. Subdural blood is often difficult to appreciate in such casesFrom the personal collection of Alice Newton, MD; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT findings in fatal abusive head trauma often reveal significant brain oedema with loss of grey-white differentiation and effacement of the ventricles. Subdural blood is often difficult to appreciate in such casesFrom the personal collection of Alice Newton, MD; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: MRI depicting subdural hygromas surrounding severe brain atrophy from abusive head trauma. This child was initially erroneously diagnosed with meningitisFrom the personal collection of Alice Newton, MD; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: MRI depicting subdural hygromas surrounding severe brain atrophy from abusive head trauma. This child was initially erroneously diagnosed with meningitisFrom the personal collection of Alice Newton, MD; used with permission [Citation ends].

Skeletal imaging

A full skeletal survey is indicated in every case of suspected physical abuse in children <2 years of age and may be performed in children up to age 3 or 4 years in select cases. If at all possible, the study should be performed at a centre where a paediatric radiologist can review the images. A follow-up skeletal survey, 2 weeks later, may identify subtle or acute injuries that may not have been visualised on the initial survey. A complete repeat survey is usually appropriate, although a limited view follow up could also be considered.[43] Complementary imaging may be indicated depending on the findings of the skeletal survey. These include CT/MRI for brain analysis and nuclear scintigraphy and/or extremity CT for a focal area of concern.[43]

Initial laboratory tests

Initial laboratory tests should include a full blood count, blood culture (if fever is present), liver function tests to assess for abdominal injury, and coagulation studies including prothrombin time, von Willebrand’s testing, and fibrinogen.[31]

Urine should be tested for infection if fever is present, and for glutaric aciduria type I. Although many countries test for this disorder in their newborn screen, it is possible for the initial test to be negative. Glutaric aciduria is generally associated with a positive family history (autosomal recessive), macrocephaly, motor delay, and learning difficulties, but these signs and symptoms may not yet be present in a young infant.[32][44][45] It is also often helpful to send urine for toxicology testing to rule out exposure to illegal substances that may be in the home.

Other investigations

If clinical signs suggest meningitis or encephalitis, lumbar puncture should be ordered unless contraindicated. In the case of traumatic brain injury, the cerebrospinal fluid shows an abundance of red blood cells and normal glucose, and may reveal xanthochromia if injury occurred at least 8 to 12 hours before presentation.

If unexplained fractures are present, testing for serum 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D, calcium, phosphate, and magnesium levels should be performed to rule out metabolic dysfunction, such as rickets. Testing for osteogenesis imperfecta is often performed even in the absence of suspicious clinical history or physical findings. Generally, this is done via blood testing for known DNA mutations associated with osteogenesis imperfecta, although in select cases skin biopsy (with testing of collagen levels produced by fibroblast cultures) is used as well.[33][46]

Given the potential legal repercussions of abusive injury, it is very important to rule out any differential diagnoses, however unlikely. Consultation with a geneticist or haematologist may be indicated.

Any unexplained infant death must have a post-mortem examination to determine possible traumatic, infectious, or other medical causes before the diagnosis of sudden infant death syndrome is made.

Legal considerations

It is important to consult with a hospital child protection team and social work services as soon as possible when a case of potential child abuse is identified.[1][22]

Child protection services will assess risk of re-injury of the patient, and risk to other children with the same carer. After assessing family and other carers, child protection services may remove children from exposure to the offending carer.

Additionally, most cases of inflicted brain injury will be referred to the police or the relevant authorities for criminal investigation.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer