History and exam

Key diagnostic factors

common

presence of risk factors

Several risk factors are associated with the development of LSC including an atopic diathesis, environmental irritants, psychiatric disorder, and dermatological disease.

underlying dermatosis

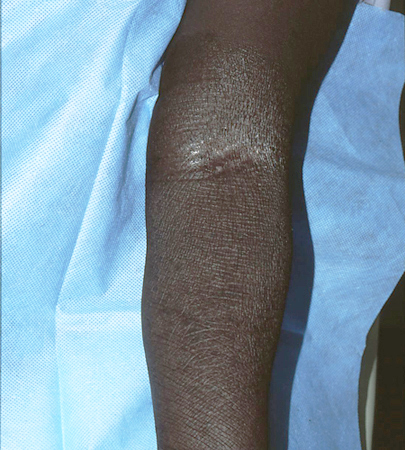

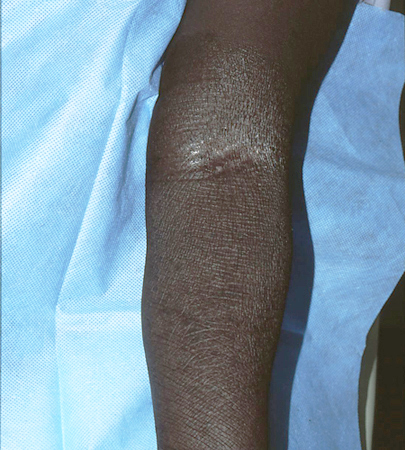

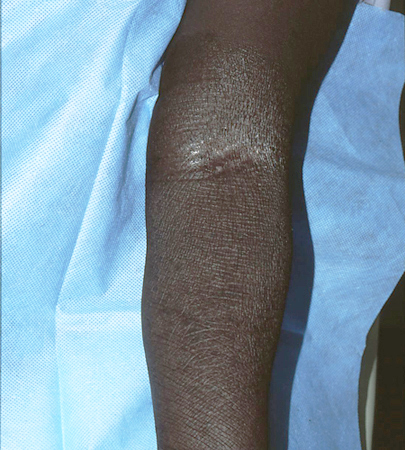

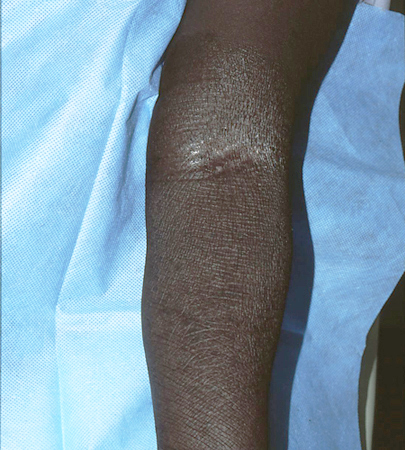

An underlying inflammatory dermatosis such as atopic dermatitis, allergic contact dermatitis, stasis dermatitis, superficial fungal (tinea and candidiasis) and dermatophyte infections, lichen sclerosis, viral warts, scabies, lice, an arthropod bite, or a cutaneous neoplasia can lead to secondary LSC.[1][2][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Secondary lichen simplex chronicus in the setting of atopic dermatitisFrom the personal collection of Dr Brian L. Swick; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Secondary lichen simplex chronicus in the setting of atopic dermatitisFrom the personal collection of Dr Brian L. Swick; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Secondary lichen simplex chronicus in the setting of atopic dermatitisFrom the personal collection of Dr Brian L. Swick; used with permission [Citation ends].

pruritus beginning during psychological stress

severe intractable itching

All patients report itching that, in most cases, is severe, intractable, worse at night, and exacerbated by heat, sweating, and clothing.[2]

Paroxysmal pruritus, leading to intense scratching and rubbing, followed by a refractory period and then another attack of pruritus defines the itch-scratch cycle characteristic of LSC.[1]

Patients commonly report that they cannot stop scratching and that it feels pleasurable to scratch.[2][19]

lichenification

Exaggeration of normal skin markings, forming a criss-cross mosaic pattern, secondary to chronic rubbing and scratching of the skin is a key feature of LSC. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Secondary lichen simplex chronicus in the setting of atopic dermatitisFrom the personal collection of Dr Brian L. Swick; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Secondary lichen simplex chronicus in the setting of atopic dermatitisFrom the personal collection of Dr Brian L. Swick; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Secondary lichen simplex chronicus in the setting of atopic dermatitisFrom the personal collection of Dr Brian L. Swick; used with permission [Citation ends].

erythematous to violaceous plaques

lesions on neck, ankles, scalp, vulva, scrotum, pubis, and extensor forearms

The most commonly affected areas, although LSC can involve any body site.[1][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Secondary lichen simplex chronicus in the setting of atopic dermatitisFrom the personal collection of Dr Brian L. Swick; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Secondary lichen simplex chronicus in the setting of atopic dermatitisFrom the personal collection of Dr Brian L. Swick; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Secondary lichen simplex chronicus in the setting of atopic dermatitisFrom the personal collection of Dr Brian L. Swick; used with permission [Citation ends].

Other diagnostic factors

common

altered pigmentation

Post-inflammatory hyper- or, less commonly, hypopigmentation may be present in patients with darker skin, particularly with chronic lesions, as a result of the mechanical damage and necrosis, respectively, of melanocytes associated with chronic pruritus.[2]

erosions

May be present on plaques secondary to excoriation.[2]

uncommon

linear fissures

Linear fissures at sites of natural skinfolds (especially with genital involvement) may develop secondary to excoriation.[2]

grouped hyperpigmented papules on the shins

Lichen amyloidosis can form on the shins in the setting of LSC.[5]

hyperpigmented patch on the interscapular back

Macular amyloidosis can form on the interscapular back in the setting of LSC, especially with notalgia paraesthetica.[4]

underlying psychiatric disorder

underlying systemic condition causing pruritus

Systemic conditions such as renal failure, obstructive biliary disease (primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis), Hodgkin's lymphoma, hyper- or hypothyroidism, and polycythaemia rubra vera can cause pruritus and thus lead to secondary LSC.[1]

Risk factors

strong

atopic diathesis

Up to 75% of patients with LSC have a personal or family history of allergic rhinitis, asthma, or atopic dermatitis.[2] Other studies demonstrate an incidence of between 20% and >90%.[2][13][14] The itch-scratch cycle, with habitual scratching, is a major component of atopic dermatitis. Disruption of the epidermal barrier, as a result of scratching, allows stimulation of type C non-myelinated nerve endings that convey itch and pain to the central nervous system, as well as providing the initial driving stimulus for LSC.[2][15]

environmental irritants

Environmental factors, including heat, sweat, rubbing of clothing, and other irritants such as harsh skincare products, stimulate type C, non-myelinated sensory nerve endings that convey itch and pain to the central nervous system and play a role in inducing the itch-scratch cycle characteristic of LSC.[2][6]

psychiatric disorder

Psychiatric conditions such as anxiety, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and dissociative experiences are often associated with LSC, but the role of these psychological factors in the pathophysiology of chronic pruritus in LSC has not yet been fully elucidated.[8][9][16]

Emotional tensions in predisposed people with an atopic diathesis can induce itch and thus begin the chronic itch-scratch cycle.[1][2]

dermatological disease

One or multiple LSC plaques can arise on skin affected by an underlying dermatosis including atopic dermatitis, allergic contact dermatitis, stasis dermatitis, superficial fungal (tinea and candidiasis) and dermatophyte infections, lichen sclerosis, viral warts, scabies, lice, an arthropod bite, or a cutaneous neoplasia.[1][2][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Secondary lichen simplex chronicus in the setting of atopic dermatitisFrom the personal collection of Dr Brian L. Swick; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Secondary lichen simplex chronicus in the setting of atopic dermatitisFrom the personal collection of Dr Brian L. Swick; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Secondary lichen simplex chronicus in the setting of atopic dermatitisFrom the personal collection of Dr Brian L. Swick; used with permission [Citation ends].

systemic conditions causing pruritus

Some systemic conditions such as renal failure, obstructive biliary disease (primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis), Hodgkin's lymphoma, hyper- or hypothyroidism, and polycythaemia rubra vera can cause pruritus and thus lead to secondary LSC.[1]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer