Initial presentation

In most patients with TBI the presentation is obvious, although some patients present with an altered mental status and little or no physical evidence of trauma.

Without a reliable witness, it is not uncommon for a patient initially thought to have an altered mental status due to stroke, seizure, psychosis, or intoxication to ultimately be found to have an occult TBI. Furthermore, in the absence of a witness, loss of consciousness or periods of confusion may not be reported to the clinician, which delays imaging in high-risk populations.

History

After initial resuscitation and management of airway, breathing, circulation, and disability (ABCD), take a focused history from every patient with a TBI or unknown cause of altered mental status. A detailed description of the traumatic event should be solicited from the patient, family members, emergency medical services, first responders, or police. Witnesses or individuals who know the patient may be helpful in ascertaining the details of the traumatic event and environment, as well as the patient’s normal level of functioning. It is important to keep the differential diagnoses broad to avoid making an error of premature closure. The history should include the following:

Mechanism of injury and detailed description of the injury

Loss of consciousness

Antegrade and/or retrograde amnesia

Seizures

Confusion, deterioration in mental status, any lucid periods

Vomiting, number of episodes

Headache, including assessment of severity

Visual disturbance

Rhinorrhoea or otorrhoea

Sensory or motor deficits

Past medical history, including any central nervous system surgery, past head trauma, haemophilia, or seizures

Drug or alcohol use

Current intoxication: shown to have an increased association with intracranial injury detected on computed tomography[106]Easter JS, Haukoos JS, Claud J, et al. Traumatic intracranial injury in intoxicated patients with minor head trauma. Acad Emerg Med. 2013 Aug;20(8):753-60.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/acem.12184/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24033617?tool=bestpractice.com

Chronic: associated with cerebral atrophy, thought to increase risk of shearing of bridging veins

Current medications, including anticoagulants.

Physical examination

A thorough physical examination must be performed after initial resuscitation. Be vigilant for occult injuries. Physical examination should include the following.

Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) and pupillary examination

Head and neck examination

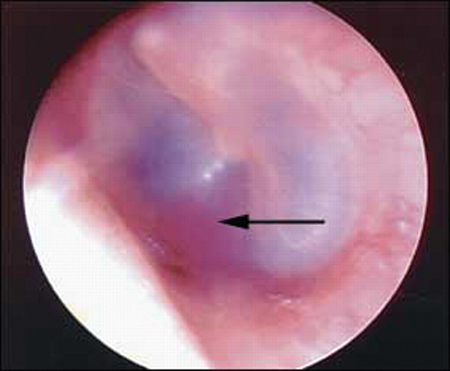

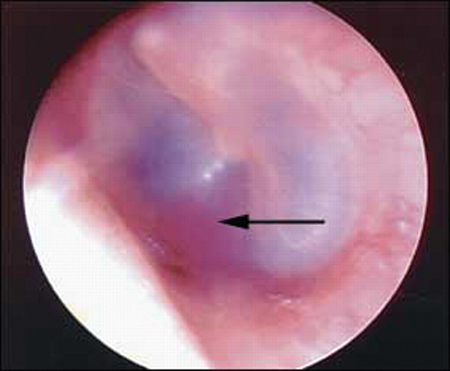

Inspection for cranial nerve deficits, periorbital or postauricular ecchymoses, cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhoea or otorrhoea, haemotympanum (signs of base of skull fracture)[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Haemotympanum: blood in the tympanic cavity of the middle ear (arrow)van Dijk GW. Practical Neurology. 2011 Feb;11(1):50-5 [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Battle's sign: superficial ecchymosis over the mastoid processvan Dijk GW. Practical Neurology. 2011 Feb;11(1):50-5 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Battle's sign: superficial ecchymosis over the mastoid processvan Dijk GW. Practical Neurology. 2011 Feb;11(1):50-5 [Citation ends].

Fundoscopic examination: can be helpful to document retinal haemorrhage (sign of abuse) and papilloedema (sign of increased intracranial pressure [ICP])[107]Maguire SA, Watts PO, Shaw AD, et al. Retinal haemorrhages and related findings in abusive and non-abusive head trauma: a systematic review. Eye (Lond). 2013 Jan;27(1):28-36.

https://www.nature.com/articles/eye2012213

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23079748?tool=bestpractice.com

Palpation of the scalp: for haematoma, crepitance, laceration, and bony deformity (markers of skull fractures)

Evaluation: for cervical spine tenderness, paraesthesias, incontinence, extremity weakness, priapism (signs of spinal cord injury)

Cardiovascular status

Requires continuous cardiac and serial blood pressure monitoring in patients with moderate or severe TBI. Any episodes of hypotension must be addressed immediately.[55]Manley G, Knudson MM, Morabito D, et al. Hypotension, hypoxia, and head injury: frequency, duration, and consequences. Arch Surg. 2001 Oct;136(10):1118-23.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamasurgery/fullarticle/392263

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11585502?tool=bestpractice.com

[56]Chesnut RM, Marshall LF, Klauber MR, et al. The role of secondary brain injury in determining outcome from severe head injury. J Trauma. 1993 Feb;34(2):216-22.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8459458?tool=bestpractice.com

Respiratory status

Requires continuous pulse oximetry in patients with moderate or severe TBI. Patients who are intubated should have continuous end-tidal CO₂ capnography. Any episodes of hypoxia or hypercapnia must be addressed immediately.[55]Manley G, Knudson MM, Morabito D, et al. Hypotension, hypoxia, and head injury: frequency, duration, and consequences. Arch Surg. 2001 Oct;136(10):1118-23.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamasurgery/fullarticle/392263

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11585502?tool=bestpractice.com

[56]Chesnut RM, Marshall LF, Klauber MR, et al. The role of secondary brain injury in determining outcome from severe head injury. J Trauma. 1993 Feb;34(2):216-22.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8459458?tool=bestpractice.com

Motor and sensory examination

Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) and pupillary examination

The GCS is widely used to assess the level of consciousness in patients with TBI, and provides prognostic information that allows the physician to plan for expected diagnostic and monitoring requirements.[45]Committee on Trauma, American College of Surgeons. ATLS: Advanced trauma life support program for doctors. 10th ed. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 2018.

[

Glasgow Coma Scale

Opens in new window

]

GCS and pupillary assessment are most reliable in haemodynamically stable patients without hypoxia or hypotension, as these may alter the patient's clinical examination.

GCS has three components: best eye response (E), best verbal response (V), and best motor response (M). Scoring for each component should be documented separately (e.g., GCS 10 = E3 V4 M3).

[

Glasgow Coma Scale

Opens in new window

]

Deficits of the motor component have the strongest correlation with poor outcome in patients with TBI.[108]Hoffmann M, Lefering R, Rueger JM, et al. Pupil evaluation in addition to Glasgow Coma Scale components in prediction of traumatic brain injury and mortality. Br J Surg. 2012 Jan;99(suppl 1):122-30.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22441866?tool=bestpractice.com

[109]Compagnone C, d'Avella D, Servadei F, et al. Patients with moderate head injury: a prospective multicenter study of 315 patients. Neurosurgery. 2009 Apr;64(4):690-6;discussion 696-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19197220?tool=bestpractice.com

If there is asymmetry between the right and left side or the upper and lower limbs, use the best motor response to calculate the GCS: this is the most reliable predictor of outcome.[45]Committee on Trauma, American College of Surgeons. ATLS: Advanced trauma life support program for doctors. 10th ed. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 2018.

Patients with oral/ocular trauma or those who are intubated, medicated, or very young can be challenging to assess. Studies have shown that alcohol intoxication has little effect on the GCS, unless the blood alcohol level is greater than 200 mg/dL.[110]Stuke L, Diaz-Arrastia R, Gentilello LM, et al. Effect of alcohol on Glasgow Coma Scale in head-injured patients. Ann Surg. 2007 Apr;245(4):651-5.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1877033

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17414616?tool=bestpractice.com

[111]Lange RT, Iverson GL, Brubacher JR, et al. Effect of blood alcohol level on Glasgow Coma Scale scores following traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2010;24(7-8):919-27.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20545447?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Adult and paediatric GCSUsed with kind permission from Dr Micelle J. Haydel [Citation ends].

The following scoring system is applied:[44]Taber KH, Warden DL, Hurley RA. Blast-related traumatic brain injury: what is known? J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006 Spring;18(2):141-5.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16720789?tool=bestpractice.com

GCS of 13-15 is associated with mild brain injury

GCS of 9-12 is associated with moderate brain injury

GCS of <9 is associated with severe brain injury.

Although a GCS of 13 is classically considered as mild, many experts believe that it should be considered within the moderate category.[10]Türedi S, Hasanbasoglu A, Gunduz A, et al. Clinical decision instruments for CT scan in minor head trauma. J Emerg Med. 2008 Apr;34(3):253-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18180129?tool=bestpractice.com

[11]Pearson WS, Ovalle F Jr, Faul M, et al. A review of traumatic brain injury

trauma center visits meeting physiologic criteria from the american college of

surgeons committee on trauma/centers for disease control and prevention field

triage guidelines. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2012 Jul-Sep;16(3):323-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22548387?tool=bestpractice.com

[12]Mena JH, Sanchez AI, Rubiano AM, et al. Effect of the modified Glasgow Coma Scale score criteria for mild traumatic brain injury on mortality prediction: comparing classic and modified Glasgow Coma Scale score model scores of 13. J Trauma. 2011 Nov;71(5):1185-92;discussion 1193.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3217203

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22071923?tool=bestpractice.com

GCS severity is inversely correlated to numerical magnitude. GCS can be serially performed by different members of the healthcare team in order to monitor neurological status; inter-rater reliability is generally considered to be good, although this has been questioned.[67]Gill MR, Reiley DG, Green SM. Interrater reliability of Glasgow Coma Scale scores in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2004 Feb;43(2):215-23.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14747811?tool=bestpractice.com

[68]Tesseris J, Pantazidis N, Routsi C, et al. A comparative study of the Reaction Level Scale (RLS 85) with Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) and Edinburgh-2 Coma Scale (Modified) (E2CS(M)). Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1991;110(1-2):65-76.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1882722?tool=bestpractice.com

[69]Elliott M. Interrater reliability of the Glasgow Coma Scale. J Neurosci Nurs. 1996 Aug;28(4):213-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8880594?tool=bestpractice.com

[70]Lindsay KW, Teasdale GM, Knill-Jones RP. Observer variability in assessing the clinical features of subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 1983 Jan;58(1):57-62.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6847910?tool=bestpractice.com

[71]Menegazzi J, Davis EA, Sucov AN, et al. Reliability of the Glasgow Coma Scale when used by emergency physicians and paramedics. J Trauma. 1993 Jan;34(1):46-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8437195?tool=bestpractice.com

A score of 13 to 15 is associated with good outcomes, although a GCS of 15 cannot be used to rule out intracranial injury. A score <9 is associated with clinical deterioration and poor outcomes. Serial GCS monitoring provides clinical warning of deterioration.

Additional tools for the assessment of consciousness

The Simplified Motor Score (obeys commands = 2, localises pain = 1, and withdraws to pain or worse = 0) has been shown to have predictive power similar to the GCS.[72]Singh B, Murad MH, Prokop LJ, et al. Meta-analysis of Glasgow coma scale and simplified motor score in

predicting traumatic brain injury outcomes. Brain Inj. 2013;27(3):293-300.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0054727

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23252405?tool=bestpractice.com

Similarly, use of a binary assessment of the GCS-motor (GCS-m) score to determine if the patient obeys commands or not (i.e., GCS-m score <6 if patient does not obey commands; GCS-m score = 6 if patient obeys commands) has been proposed as a triage tool for out-of-hospital care. One retrospective analysis found a GCS-m score of <6 is similarly predictive of serious injury as the total GCS score.[73]Kupas DF, Melnychuk EM, Young AJ. Glasgow Coma Scale motor component ("patient does not follow commands") performs similarly to total Glasgow Coma Scale in predicting severe injury in trauma patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2016 Dec;68(6):744-50.

http://www.annemergmed.com/article/S0196-0644(16)30295-5/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27436703?tool=bestpractice.com

The FOUR scale, which adds brainstem reflexes and respiratory patterns to motor and eye findings, has also been shown to have similar predictive power to the GCS.[74]Nyam TE, Ao KH, Hung SY, et al. FOUR score predicts early outcome in patients after traumatic brain injury. Neurocrit Care. 2017 Apr;26(2):225-31.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27873233?tool=bestpractice.com

[75]Kasprowicz M, Burzynska M, Melcer T, et al. A comparison of the Full Outline of UnResponsiveness (FOUR) score and Glasgow Coma Score(GCS) in predictive modelling in traumatic brain injury. Br J Neurosurg. 2016;30(2):211-20.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27001246?tool=bestpractice.com

Pupillary examination

Pupillary reflexes function as an indication of both underlying pathology and severity of injury, and should be monitored serially.[76]Meyer S, Gibb T, Jurkovich GJ. Evaluation and significance of the pupillary light reflex in trauma patients. Ann Emerg Med. 1993 Jun;22(6):1052-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8503525?tool=bestpractice.com

The pupillary examination can be assessed in an unconscious patient or in a patient receiving neuromuscular blocking agents or sedation.[16]Maas AI, Stocchetti N, Bullock R. Moderate and severe traumatic brain injury in adults. Lancet Neurol. 2008 Aug;7(8):728-41.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18635021?tool=bestpractice.com

[76]Meyer S, Gibb T, Jurkovich GJ. Evaluation and significance of the pupillary light reflex in trauma patients. Ann Emerg Med. 1993 Jun;22(6):1052-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8503525?tool=bestpractice.com

Pupils should be examined for size, symmetry, direct/consensual light reflexes, and duration of dilation/fixation. Abnormal pupillary reflexes can suggest herniation or brainstem injury. Orbital trauma, pharmacological agents, or direct cranial nerve III trauma may result in pupillary changes in the absence of increased ICP, brainstem pathology, or herniation.

Pupil size:

The normal diameter of the pupil is between 2-5 mm, and although both pupils should be equal in size, a 1-mm difference is considered a normal variant.

Abnormal size is noted by >1 mm difference between pupils.

Pupil symmetry:

Normal pupils are round, but can be irregular due to ophthalmological surgeries.

Abnormal symmetry may result from compression of CNIII, which can cause a pupil to initially become oval before becoming dilated and fixed.

Direct light reflex:

Normal pupils constrict briskly in response to light, but may be poorly responsive due to ophthalmological medications.

Abnormal light reflex may be seen in sluggish pupillary responses associated with increased ICP. A non-reactive, fixed pupil has <1 mm response to bright light and is associated with severely increased ICP.

Laboratory investigations

Baseline laboratory investigations in patients with moderate to severe TBI should include:

Full blood count including platelets

Serum electrolytes and urea

Serum glucose

Coagulation status: prothrombin time, international normalised ratio, activated partial prothrombin time

Blood alcohol level and toxicology screening if indicated.

Arterial blood gas is not typically indicated in TBI, as the decision to secure a definitive airway is based on clinical findings and expected course of hospitalisation. Any patient with TBI who is not spontaneously breathing, not able to maintain an open airway, or not able to maintain >90% oxygen saturation with supplementary oxygen, requires a definitive airway. The dogmatic intubation of all trauma patients with a GCS of <9 has been challenged.[113]Hatchimonji JS, Dumas RP, Kaufman EJ, et al. Questioning dogma: does a GCS of 8 require intubation? Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2021 Dec;47(6):2073-9.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7223660

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32382780?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients who are not intubated must have close continuous monitoring of pulse oximetry and end-tidal CO₂.

Imaging in patients with TBI and suspected intracranial injury

Consensus recommendations from the American College of Radiology support non-contrast CT use as a first-line imaging modality in patients with TBI.[114]Expert Panel on Neurological Imaging; Shih RY, Burns J, Ajam AA. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® head trauma: 2021 update. J Am Coll Radiol. 2021 May;18(5S):S13-36.

https://www.jacr.org/article/S1546-1440(21)00025-9/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33958108?tool=bestpractice.com

Computed tomography (CT)

Non-contrast CT is the imaging modality of choice for patients with TBI and suspected intracranial injury; it is able to detect the vast majority of clinically important injuries and can guide in the medical and surgical management of TBI.[18]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Head injury: assessment and early management. May 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng232

[45]Committee on Trauma, American College of Surgeons. ATLS: Advanced trauma life support program for doctors. 10th ed. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 2018.

An immediate CT is indicated in all patients with TBI with penetrating injuries; suspected basilar, depressed, or open fracture; GCS <13; or focal neurological deficits.

Several guidelines recommend, or suggest consideration of, CT head imaging for anticoagulated patients after minor head injury, regardless of symptoms.[18]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Head injury: assessment and early management. May 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng232

[99]American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Policies Subcommittee (Writing Committee) on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury; Valente JH, Anderson JD, Paolo WF, et al. Clinical policy: critical issues in the management of adult patients presenting to the emergency department with mild traumatic brain injury: approved by ACEP board of directors, February 1, 2023 clinical policy endorsed by the Emergency Nurses Association (April 5, 2023). Ann Emerg Med. 2023 May;81(5):e63-105.

https://www.annemergmed.com/article/S0196-0644(23)00028-8/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37085214?tool=bestpractice.com

[100]Vos PE, Alekseenko Y, Battistin L, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury. Eur J Neurol. 2012 Feb;19(2):191-8.

https://www.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03581.x

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22260187?tool=bestpractice.com

UK guidelines recommend that a CT head scan within 8 hours of the injury should be considered for all patients taking anticoagulants.[18]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Head injury: assessment and early management. May 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng232

However, the supporting evidence base is limited.[99]American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Policies Subcommittee (Writing Committee) on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury; Valente JH, Anderson JD, Paolo WF, et al. Clinical policy: critical issues in the management of adult patients presenting to the emergency department with mild traumatic brain injury: approved by ACEP board of directors, February 1, 2023 clinical policy endorsed by the Emergency Nurses Association (April 5, 2023). Ann Emerg Med. 2023 May;81(5):e63-105.

https://www.annemergmed.com/article/S0196-0644(23)00028-8/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37085214?tool=bestpractice.com

[100]Vos PE, Alekseenko Y, Battistin L, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury. Eur J Neurol. 2012 Feb;19(2):191-8.

https://www.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03581.x

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22260187?tool=bestpractice.com

[101]Fuller GW, Evans R, Preston L, et al. Should adults with mild head injury who are receiving direct oral anticoagulants undergo computed tomography scanning? A systematic review. Ann Emerg Med. 2019 Jan;73(1):66-75.

https://www.annemergmed.com/article/S0196-0644(18)30652-8/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30236417?tool=bestpractice.com

The following CT findings are associated with a poor outcome in TBI: midline shift, subarachnoid haemorrhage into, or compression/obliteration of, the basal cisterns.[115]Bullock MR, Chesnut R, Ghajar J, et al; Surgical Management of Traumatic Brain Injury Author Group. Surgical management of traumatic parenchymal lesions. Neurosurgery. 2006 Mar;58(3 suppl):S25-46;discussion Si-iv.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16540746?tool=bestpractice.com

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Indicated when the clinical picture remains unclear after a CT, in order to identify more subtle lesions, such as those found in diffuse axonal injury. MRI is, however, frequently impractical in the acute setting.[116]Expert Panel on Pediatric Imaging; Ryan ME, Pruthi S, Desai NK, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® head trauma - child. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020 May;17(5s):S125-37.

https://www.jacr.org/article/S1546-1440(20)30114-9/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32370957?tool=bestpractice.com

MRI is contraindicated if there is any suspicion that a metal object has penetrated the skull.

In high-volume paediatric trauma centres, MRI may be performed as an initial investigation to decrease radiation exposure. One prospective cohort study found that fast MRI was feasible and accurate relative to CT in clinically stable children with suspected TBI.[117]Lindberg DM, Stence NV, Grubenhoff JA, et al. Feasibility and Accuracy of Fast MRI Versus CT for Traumatic Brain Injury in Young Children. Pediatrics. 2019 Oct;144(4):.

https://www.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-0419

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31533974?tool=bestpractice.com

Transcranial doppler (TCD)

Has been used in the intensive care unit setting to monitor cerebral haemodynamics in both adults and children with severe TBI. TCD monitors blood flow velocity in large intracerebral arteries, which is altered in the setting of elevated intracranial pressure.

Some studies have suggested a role for TCD in patients with TBI in the accident and emergency department but, to date, the majority of use is in the intensive care unit setting.[118]Geeraerts T, Velly L, Abdennour L, et al. Management of severe traumatic brain injury (first 24 hours). Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2018 Apr;37(2):171-86.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352556817303703?via%3Dihub

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29288841?tool=bestpractice.com

[119]Roldán M, Abay TY, Kyriacou PA. Non-invasive techniques for multimodal monitoring in traumatic brain injury: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurotrauma. 2020 Dec 1;37(23):2445-53.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32821023?tool=bestpractice.com

[120]Caldas J, Bittencourt Rynkowski C, Robba C. POCUS, how can we include the brain? An overview. J Anesth Analg Crit Care. 2022;2:55.

https://janesthanalgcritcare.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s44158-022-00082-3

Mild TBI (concussion)

The diagnosis of mild TBI (mTBI) is dependent on careful history taking and examination. The patient’s history and collateral interviews are important in generating a diagnosis.[121]Ruff RM, Iverson GL, Barth JT, et al; NAN Policy and Planning Committee. Recommendations for diagnosing a mild traumatic brain injury: a National Academy of Neuropsychology education paper. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2009 Feb;24(1):3-10.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19395352?tool=bestpractice.com

As per the definitions of TBI, careful assessment of loss of consciousness, retrograde amnesia, post-traumatic amnesia, confusion and disorientation, and focal neurological deficit should be performed.[121]Ruff RM, Iverson GL, Barth JT, et al; NAN Policy and Planning Committee. Recommendations for diagnosing a mild traumatic brain injury: a National Academy of Neuropsychology education paper. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2009 Feb;24(1):3-10.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19395352?tool=bestpractice.com

In addition, signs and symptoms may be influenced by alcohol, drugs, or medications.[121]Ruff RM, Iverson GL, Barth JT, et al; NAN Policy and Planning Committee. Recommendations for diagnosing a mild traumatic brain injury: a National Academy of Neuropsychology education paper. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2009 Feb;24(1):3-10.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19395352?tool=bestpractice.com

CT is typically normal following mild TBI, although a significant number of patients are left with neurocognitive deficits and may benefit from follow-up with a neurologist and consideration of diffusion tensor imaging.[122]Aoki Y, Inokuchi R, Gunshin M, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging

studies of mild traumatic brain injury: a meta-analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg

Psychiatry. 2012 Sep;83(9):870-6.

http://jnnp.bmj.com/content/83/9/870.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22797288?tool=bestpractice.com

[123]Kraus MF, Susmaras T, Caughlin BP, et al. White matter integrity and cognition in chronic traumatic brain injury: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Brain. 2007 Oct;130(Pt 10):2508-19.

https://academic.oup.com/brain/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/brain/awm216

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17872928?tool=bestpractice.com

Imaging in patients with mild TBI

The use of CT in patients with isolated mild TBI is controversial.

The New Orleans Criteria and the Canadian CT Head Rule are highly sensitive (99% to 100%) in patients with a GCS of 13-15, and in patients with and without loss of consciousness.[124]Pandor A, Goodacre S, Harnan S, et al. Diagnostic management strategies for adults and children with minor head injury: a systematic review and an economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2011 Aug;15(27):1-202.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK100016

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21806873?tool=bestpractice.com

[125]Stiell IG, Clement CM, Rowe BH, et al. Comparison of the Canadian CT Head Rule and the New Orleans Criteria in patients with minor head injury. JAMA. 2005 Sep 28;294(12):1511-8.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/201596

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16189364?tool=bestpractice.com

[126]Stein SC, Fabbri A, Servadei F, et al. A critical comparison of clinical decision instruments for computed tomographic scanning in mild closed traumatic brain injury in adolescents and adults. Ann Emerg Med. 2009 Feb;53(2):180-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18339447?tool=bestpractice.com

[127]Smits M, Dippel DW, de Haan GG, et al. External validation of the Canadian CT Head Rule and the New Orleans Criteria for CT scanning in patients with minor head injury. JAMA. 2005 Sep 28;294(12):1519-25.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/201595

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16189365?tool=bestpractice.com

[128]Papa L, Stiell IG, Clement CM, et al. Performance of the Canadian CT Head Rule and the New Orleans Criteria for predicting any traumatic intracranial injury on computed tomography in a United States Level I trauma center. Acad Emerg Med. 2012 Jan;19(1):2-10.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01247.x/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22251188?tool=bestpractice.com

[129]Haydel MJ, Preston CA, Mills TJ, et al. Indications for computed tomography in patients with minor head injury. N Engl J Med. 2000 Jul 13;343(2):100-5.

http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJM200007133430204#t=article

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10891517?tool=bestpractice.com

Both instruments include the following variables: some form of vomiting, advanced age, altered mental status, and signs of head trauma on physical examination.

In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines for the approach to patients with mild TBI include the variables from the Canadian CT Head Rule.[18]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Head injury: assessment and early management. May 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng232

In the US, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has adapted the variables from the New Orleans Criteria in the approach to adult patients with mild TBI.

CDC: mild TBI pocket guide

Opens in new window

New Orleans criteria

CT is indicated in patients with minor head trauma (minor head injury defined as loss of consciousness in patients with normal findings on a brief neurological examination and a GCS score of 15, as determined by a physician upon arrival at the accident and emergency department) with any one of the following:[129]Haydel MJ, Preston CA, Mills TJ, et al. Indications for computed tomography in patients with minor head injury. N Engl J Med. 2000 Jul 13;343(2):100-5.

http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJM200007133430204#t=article

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10891517?tool=bestpractice.com

High risk (for neurosurgical intervention)

Headache

Vomiting

Aged over 60 years

Drug or alcohol intoxication

Persistent anterograde amnesia (deficits in short-term memory)

Evidence of traumatic soft-tissue or bone injury above clavicles

Seizure (suspected or witnessed).

Where possible, a history of coagulopathy should be obtained and considered with respect to CT scanning.

Canadian CT head rule

CT is indicated in patients with minor head injuries (minor head injury defined as witnessed loss of consciousness, definite amnesia, or witnessed disorientation in patients with a GCS score of 13-15) with any one of the following:[7]Stiell IG, Wells GA, Vandemheen K, et al. The Canadian CT head rule for patients with minor head injury. Lancet. 2001 May 5;357(9266):1391-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11356436?tool=bestpractice.com

[

Canadian Head CT Rule for Minor Head Injury

Opens in new window

]

Assessing infants and children with suspected TBI

Validated clinical decision rules, such as the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) decision rule, effectively identify children at low risk for intracranial injury (and those at increased risk, for whom head CT may be indicated).[130]Lumba-Brown A, Yeates KO, Sarmiento K, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guideline on the diagnosis and management of mild traumatic brain injury among children. JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Nov 1;172(11):e182853.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7006878

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30193284?tool=bestpractice.com

Clinical decision rules to identify children who benefit from CT after head injury have been derived from three large prospective studies (PECARN, CATCH, and CHALICE).[131]Kuppermann N, Holmes JF, Dayan PS, et al. Identification of children at very low risk of

clinically-important brain injuries after head trauma: a prospective cohort

study. Lancet. 2009 Oct 3;374(9696):1160-70.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19758692?tool=bestpractice.com

[132]Osmond MH, Klassen TP, Wells GA, et al. CATCH: a clinical decision rule for the use of computed tomography in children with minor head injury. CMAJ. 2010 Mar 9;182(4):341-8.

http://www.cmaj.ca/content/182/4/341.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20142371?tool=bestpractice.com

[133]Dunning J, Daly JP, Lomas JP, et al. Derivation of the children's head injury algorithm for the prediction of important clinical events decision rule for head injury in children. Arch Dis Child. 2006 Nov;91(11):885-91.

http://adc.bmj.com/content/91/11/885

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17056862?tool=bestpractice.com

The PECARN clinical decision rule has the highest sensitivity for identifying children with clinically important TBI.[134]Babl FE, Borland ML, Phillips N, et al. Accuracy of PECARN, CATCH, and CHALICE head injury decision rules in children: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2017 Jun 17;389(10087):2393-402.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28410792?tool=bestpractice.com

Based on the PECARN clinical decision rule, CT is indicated for all children with a GCS score <15, altered mental status (agitation, somnolence, repetitive questioning, slow to verbal response), palpable skull fracture, or suspected basilar skull fracture.[131]Kuppermann N, Holmes JF, Dayan PS, et al. Identification of children at very low risk of

clinically-important brain injuries after head trauma: a prospective cohort

study. Lancet. 2009 Oct 3;374(9696):1160-70.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19758692?tool=bestpractice.com

Further indications for CT differ based on patient age.

Additional PECARN indications for CT in children under the age of 2 years:[131]Kuppermann N, Holmes JF, Dayan PS, et al. Identification of children at very low risk of

clinically-important brain injuries after head trauma: a prospective cohort

study. Lancet. 2009 Oct 3;374(9696):1160-70.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19758692?tool=bestpractice.com

Loss of consciousness >3 seconds

Non-frontal scalp haematoma

Not acting normal (per parent)

Severe mechanism of injury: motor vehicle accident with ejection, death of passenger, rollover, struck by vehicle, fall >3 feet (0.9m), head struck by high impact object.

Observation for 6 hours is an option for patients >3 months (and <2 years) if no more than one of the four criteria is present. CT is indicated for new, worsening, or unresolved symptoms by 6 hours.

Additional PECARN indications for CT in children aged 2 years or older:[131]Kuppermann N, Holmes JF, Dayan PS, et al. Identification of children at very low risk of

clinically-important brain injuries after head trauma: a prospective cohort

study. Lancet. 2009 Oct 3;374(9696):1160-70.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19758692?tool=bestpractice.com

Loss of consciousness

Severe headache

Vomiting

Severe mechanism of injury: motor vehicle accident with ejection, death of passenger, rollover, struck by vehicle, fall >3 feet (0.9m), head struck by high impact object.

Observation for 6 hours is an option for patients >2 years if no more than one of the four criteria is present. CT is indicated for new, worsening, or unresolved symptoms by 6 hours.

Routine use of imaging to diagnose mild TBI in children in the acute setting is not recommended.[116]Expert Panel on Pediatric Imaging; Ryan ME, Pruthi S, Desai NK, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® head trauma - child. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020 May;17(5s):S125-37.

https://www.jacr.org/article/S1546-1440(20)30114-9/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32370957?tool=bestpractice.com

[130]Lumba-Brown A, Yeates KO, Sarmiento K, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guideline on the diagnosis and management of mild traumatic brain injury among children. JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Nov 1;172(11):e182853.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7006878

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30193284?tool=bestpractice.com

BMJ: clinical decision making tools image

Opens in new window

Post-injury monitoring

Post-trauma monitoring will vary depending on the clinical findings and the results of the diagnostic work-up. Patients with moderate or severe TBI should be admitted to a hospital with neurosurgical consultants, and an intensive care unit able to provide monitoring to identify and limit secondary brain injury. Most patients with polytrauma and/or those who do not attain a normal neurological examination while in the accident and emergency department will benefit from a similar hospitalisation, and may require re-imaging as the clinical picture changes.

One systematic review found that patients with mild TBI and an initially abnormal CT did not benefit from routine repeat CT, but should be re-imaged based on neurological deterioration.[135]Almenawer SA, Bogza I, Yarascavitch B, et al. The value of scheduled repeat cranial computed tomography after mild head injury: single-center series and meta-analysis. Neurosurgery. 2013 Jan;72(1):56-62;discussion 63-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23254767?tool=bestpractice.com

Post-concussive syndrome (the persistence of physical, cognitive, emotional, and sleep symptoms beyond the acute post-injury period) is monitored using the same symptom scales employed in the acute phase of the injury.[136]Committee on Sports-Related Concussions in Youth; Board on Children, Youth, and Families; Institute of Medicine; National Research Council; Graham R, Rivara FP, Ford MA, et al. Sports-related concussions in youth: improving the science, changing the culture. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2014.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK169016

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24199265?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients with a normal neurological examination and negative CT scan (or where scanning was not indicated), may be discharged home after 2 hours of observation under the care of a responsible individual.[125]Stiell IG, Clement CM, Rowe BH, et al. Comparison of the Canadian CT Head Rule and the New Orleans Criteria in patients with minor head injury. JAMA. 2005 Sep 28;294(12):1511-8.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/201596

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16189364?tool=bestpractice.com

[137]Blostein P, Jones SJ. Identification and evaluation of patients with mild traumatic brain injury: results of a national survey of level I trauma centers. J Trauma. 2003 Sep;55(3):450-3.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14501885?tool=bestpractice.com

[138]Servadei F, Teasdale G, Merry G. Defining acute mild head injury in adults: a proposal based on prognostic factors, diagnosis, and management. J Neurotrauma. 2001 Jul;18(7):657-64.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11497092?tool=bestpractice.com

[139]Ropper AH, Gorson KC. Clinical practice: concussion. N Engl J Med. 2007 Jan 11;356(2):166-72.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17215534?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients should be provided with written information regarding signs and symptoms that should prompt a return to the accident and emergency department, including focal weakness, persistent or worsening headache or vomiting, decrease in consciousness, rhinorrhoea, otorrhoea, or agitation.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Battle's sign: superficial ecchymosis over the mastoid processvan Dijk GW. Practical Neurology. 2011 Feb;11(1):50-5 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Battle's sign: superficial ecchymosis over the mastoid processvan Dijk GW. Practical Neurology. 2011 Feb;11(1):50-5 [Citation ends].