Vaginal discharge is a common symptom seen by clinicians. It may be physiological or pathological.[9]Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. Jul 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/toc.htm

British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH) guidelines

Opens in new window

Physiological discharge can vary in character with changes in age (pre-pubertal, reproductive, or post-menopausal), hormones (during pregnancy or when using hormonal contraception), or local factors such as menstruation, intrauterine device, or postnatal state.[1]Watson LJ, James KE, Hatoum Moeller IJ, et al. Vulvovaginal discomfort is common in both premenopausal and postmenopausal women. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2019 Apr;23(2):164-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30741753?tool=bestpractice.com

[10]Mitchell H. Vaginal discharge-causes, diagnosis, and treatment. BMJ. 2004 May 29;328(7451):1306-8.

https://www.bmj.com/content/328/7451/1306.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15166070?tool=bestpractice.com

Pathological causes are commonly due to infection: mainly bacterial vaginosis, vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC), and trichomoniasis, which together account for 90% of vaginitis cases.[11]Sobel JD. Vulvovaginitis in healthy women. Compr Ther. 1999 Jun-Jul;25(6-7):335-46.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10470518?tool=bestpractice.com

Non-infectious causes include genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM), desquamative inflammatory vaginitis, dermatitis, foreign body, allergens, and inadequate hygiene.[12]Sobel JD. Pathogenesis of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Curr Inf Dis Rep. 2002 Dec;4(6):514-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12433327?tool=bestpractice.com

[13]Goje O, Munoz JL. Vulvovaginitis: find the cause to treat it. Cleve Clin J Med. 2017 Mar;84(3):215-24.

https://www.doi.org/10.3949/ccjm.84a.15163

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28322677?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Angelou K, Grigoriadis T, Diakosavvas M, et al. The genitourinary syndrome of menopause: an overview of the recent data. Cureus. 2020 Apr 8;12(4):e7586.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7212735

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32399320?tool=bestpractice.com

Bacterial vaginosis

Bacterial vaginosis is the most common vaginal infection, with a prevalence of 21.2 million (29.2%) in the US in women aged 14 to 49 years.[15]Koumans EH, Sternberg M, Bruce C, et al. The prevalence of bacterial vaginosis in the United States, 2001-2004; associations with symptoms, sexual behaviors, and reproductive health. Sex Transm Dis. 2007 Nov;34(11):864-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17621244?tool=bestpractice.com

Among community-dwelling older women in the US (aged 62-90 years), bacterial vaginosis prevalence has been reported to be 38%.[16]Hoffmann JN, You HM, Hedberg EC, et al. Prevalence of bacterial vaginosis and Candida among postmenopausal women in the United States. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2014 Nov;69 Suppl 2(suppl 2):S205-14.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4303100

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25360022?tool=bestpractice.com

Global prevalence is high, ranging from 20% to 60% across regions.[17]Peebles K, Velloza J, Balkus JE, et al. High global burden and costs of bacterial vaginosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Dis. 2019 May;46(5):304-11.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30624309?tool=bestpractice.com

[18]Bautista CT, Wurapa E, Sateren WB, et al. Bacterial vaginosis: a synthesis of the literature on etiology, prevalence, risk factors, and relationship with chlamydia and gonorrhea infections. Mil Med Res. 2016;3:4.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4752809

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26877884?tool=bestpractice.com

Bacterial vaginosis is characterised by a complex change in the vaginal flora, which leads to a reduction of the normally dominant lactobacilli.[19]Fredricks DN, Fiedler TL, Marrazzo JM. Molecular identification of bacteria associated with bacterial vaginosis. N Engl J Med. 2005 Nov 3;353(18):1899-911.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa043802?

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16267321?tool=bestpractice.com

These lactobacilli are replaced by an increased concentration of other organisms, especially anaerobes such as Gardnerella vaginalis, Mycoplasma hominis, Prevotella species, Porphyromonas species, Bacteroides species, anaerobic Peptostreptococcus species, Fusobacterium species, or Atopobium vaginae.[20]Hill GB. The microbiology of bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993 Aug;169(2 Pt 2):450-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8357043?tool=bestpractice.com

These organisms, which break down vaginal peptides into amines and cause the typical discharge in patients with bacterial vaginosis, produce large amounts of proteolytic carboxylase enzymes.

Patients treated for bacterial vaginosis have a high risk of recurrence within 3 months.[21]Hay P. Recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2000 Dec;2(6):506-12.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11095900?tool=bestpractice.com

[22]Sobel JD, Kaur N, Woznicki NA, et al. Prognostic indicators of recurrence of bacterial vaginosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2019 May;57(5):e00227-19.

https://www.doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00227-19

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30842235?tool=bestpractice.com

Routine treatment of women with asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis is not recommended, mainly due to low response rates and increased incidence of candidiasis after therapy.[23]Schwebke J, Desmond R. A randomized trial of metronidazole in asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis to prevent the acquisition of sexually transmitted diseases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007 Jun;196(6):517;e1-6.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1993882

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17547876?tool=bestpractice.com

However, treatment of asymptomatic women with bacterial vaginosis results in a lower rate of subsequent Chlamydia infection.[23]Schwebke J, Desmond R. A randomized trial of metronidazole in asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis to prevent the acquisition of sexually transmitted diseases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007 Jun;196(6):517;e1-6.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1993882

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17547876?tool=bestpractice.com

Bacterial vaginosis infection is associated with objective evidence of acute upper genital tract infection, vaginal cuff cellulitis, abscess after transvaginal hysterectomy, post-voluntary termination of pregnancy, endometritis, and pelvic inflammatory disease.[24]Peipert J, Montagno AB, Cooper AS, et al. Bacterial vaginosis as a risk factor for upper genital tract infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997 Nov;177(5):1184-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9396917?tool=bestpractice.com

[25]British Association for Sexual Health and HIV. UK National guideline for the management of bacterial vaginosis. 2012 [internet publication].

https://www.bashh.org/documents/4413.pdf

[26]Taha TE, Hoover DR, Dallabetta GA, et al. Bacterial vaginosis and disturbances of vaginal flora: association with increased acquisition of HIV. AIDS. 1998 Sep 10;12(13):1699-706.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9764791?tool=bestpractice.com

Treatment of male partners of patients with bacterial vaginosis does not increase the cure rate; therefore, it is not routinely recommended.[9]Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. Jul 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/toc.htm

[27]Sena AC, Miller WC, Hobbs MM, et al. Trichomonas vaginalis infection in male sexual partners: implications for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Clin Infect Dis. 2007 Jan 1;44(1):13-22.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17143809?tool=bestpractice.com

[28]Vutyavanich T, Pongsuthirak P, Vannareumol P, et al. A randomized double-blind trial of tinidazole treatment of the sexual partners of females with bacterial vaginosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1993 Oct;82(4 Pt 1):550-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8377981?tool=bestpractice.com

Bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy is a risk factor for preterm premature rupture of membranes, preterm delivery, low birth weight, and spontaneous abortion.[9]Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. Jul 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/toc.htm

[29]Leitich H, Bodner-Adler B, Brunbauer M, et al. Bacterial vaginosis as a risk factor for preterm delivery: a meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003 Jul;189(1):139-47.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12861153?tool=bestpractice.com

[30]Hillier SL, Nugent RP, Eschenbach DA, et al. Association between bacterial vaginosis and preterm delivery of a low-birth-weight infant. The Vaginal Infections and Prematurity Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995 Dec 28;333(26):1737-42.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJM199512283332604

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7491137?tool=bestpractice.com

Antibiotic therapy effectively eradicates bacterial vaginosis during therapy, but does not prevent preterm birth.[31]Brocklehurst P, Gordon A, Heatley E, et al. Antibiotics for treating bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Jan 31;(1):CD000262.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD000262.pub4/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23440777?tool=bestpractice.com

[32]Klebanoff MA, Schuit E, Lamont RF, et al. Antibiotic treatment of bacterial vaginosis to prevent preterm delivery: systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2023 Mar;37(3):239-51.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10171232

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36651636?tool=bestpractice.com

Currently, in the general obstetric population, data are insufficient to support screening for or treatment of bacterial vaginosis to reduce risk for preterm birth.[9]Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. Jul 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/toc.htm

[31]Brocklehurst P, Gordon A, Heatley E, et al. Antibiotics for treating bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Jan 31;(1):CD000262.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD000262.pub4/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23440777?tool=bestpractice.com

[32]Klebanoff MA, Schuit E, Lamont RF, et al. Antibiotic treatment of bacterial vaginosis to prevent preterm delivery: systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2023 Mar;37(3):239-51.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10171232

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36651636?tool=bestpractice.com

[33]Kahwati LC, Clark R, Berkman N, et al. Screening for bacterial vaginosis in pregnant adolescents and women to prevent preterm delivery: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2020 Apr 7;323(13):1293-1309.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2764188

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32259235?tool=bestpractice.com

[34]Kahwati LC, Clark R, Berkman ND, et al. Screening for bacterial vaginosis in pregnant adolescents and women to prevent preterm delivery [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2020 Apr. Report No.: 19-05259-EF-1.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK555831

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32298060?tool=bestpractice.com

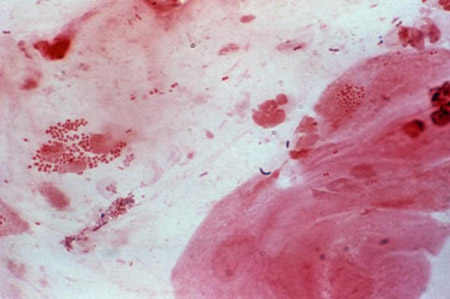

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Photomicrograph revealing bacteria adhering to vaginal epithelial cells, known as clue cellsCDC Image Library; M. Rein [Citation ends].

Trichomoniasis

Trichomonas vaginalis (TV), a flagellated protozoan parasite, causes trichomoniasis. It accounts for 4% to 35% of vaginitis in symptomatic women, and is considerably more common in black women than in white women.[9]Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. Jul 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/toc.htm

[35]Anderson MR, Klink K, Cohrssen A. Evaluation of vaginal complaints. JAMA. 2004 Mar 17;291(11):1368-79.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15026404?tool=bestpractice.com

Trichomoniasis is estimated to be the most prevalent non-viral sexually transmitted infection (STI) worldwide, affecting approximately 2.1% of females in the US.[9]Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. Jul 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/toc.htm

TV is usually found in the vagina, urethra, and paraurethral glands of infected patients.[36]Krieger JN. Urologic aspects of trichomoniasis. Invest Urol. 1981 May;18(8):411-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7014514?tool=bestpractice.com

[37]Sherrard J, Pitt R, Hobbs KR, et al. British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH) United Kingdom national guideline on the management of Trichomonas vaginalis 2021. Int J STD AIDS. 2022 Jul;33(8):740-50.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35701863?tool=bestpractice.com

It is associated with a high prevalence of co-infection with other STIs.

Concurrent treatment of sex partners is recommended.[9]Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. Jul 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/toc.htm

[27]Sena AC, Miller WC, Hobbs MM, et al. Trichomonas vaginalis infection in male sexual partners: implications for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Clin Infect Dis. 2007 Jan 1;44(1):13-22.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17143809?tool=bestpractice.com

[37]Sherrard J, Pitt R, Hobbs KR, et al. British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH) United Kingdom national guideline on the management of Trichomonas vaginalis 2021. Int J STD AIDS. 2022 Jul;33(8):740-50.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35701863?tool=bestpractice.com

[38]Sherrard J, Wilson J, Donders G, et al. 2018 European (IUSTI/WHO) International Union against sexually transmitted infections (IUSTI) World Health Organisation (WHO) guideline on the management of vaginal discharge. Int J STD AIDS. 2018 Nov;29(13):1258-72.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30049258?tool=bestpractice.com

Trichomoniasis is associated with a 1.5-fold increased risk for HIV-1 acquisition; it may also enhance genital shedding of HIV in women (which may be reduced by treatment).[9]Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. Jul 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/toc.htm

[39]Røttingen JA, Cameron DW, Garnett GP. A systematic review of the epidemiologic interactions between classic sexually transmitted diseases and HIV: how much really is known? Sex Transm Dis. 2001 Oct;28(10):579-97.

https://www.doi.org/10.1097/00007435-200110000-00005

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11689757?tool=bestpractice.com

[40]Wang CC, McClelland RS, Reilly M, et al. The effect of treatment of vaginal infections on shedding of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Infect Dis. 2001 Apr 1;183(7):1017-22.

https://www.doi.org/10.1086/319287

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11237825?tool=bestpractice.com

[41]Kissinger P, Amedee A, Clark RA, et al. Trichomonas vaginalis treatment reduces vaginal HIV-1 shedding. Sex Transm Dis. 2009 Jan;36(1):11-6.

https://www.doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318186decf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19008776?tool=bestpractice.com

Screening for trichomoniasis is recommended for women living with HIV, and might be considered for those receiving care in high-prevalence settings (e.g., sexually transmitted disease clinics and correctional facilities) or at high risk for infection (e.g., multiple sexual partners, transactional sex, drug misuse, or history of STIs or incarceration).[9]Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. Jul 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/toc.htm

Trichomoniasis is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes such as preterm birth, but treatment has not been shown to reduce perinatal morbidity.[9]Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. Jul 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/toc.htm

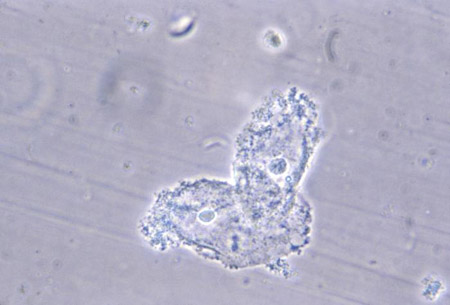

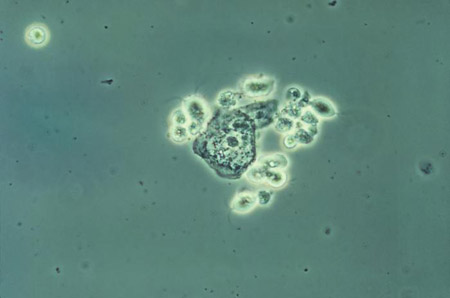

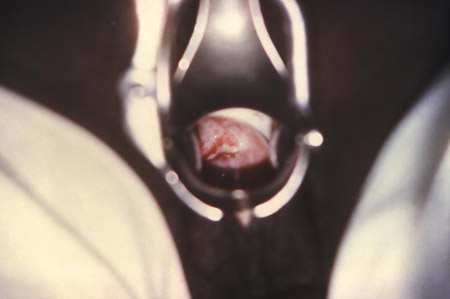

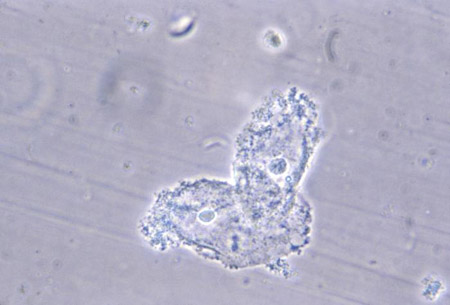

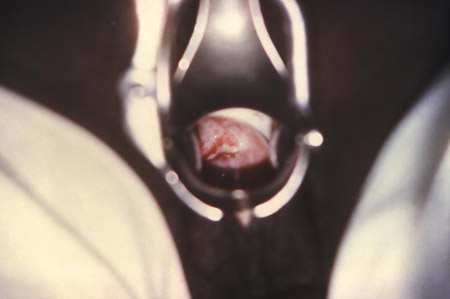

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Phase contrast wet mount micrograph of a vaginal discharge revealing the presence of Trichomonas vaginalisprotozoa CDC Image Library [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Trichomonasvaginitis with copious purulent discharge emanating from the cervical os CDC Image Library [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Trichomonasvaginitis with copious purulent discharge emanating from the cervical os CDC Image Library [Citation ends].

Vulvovaginal candidiasis

Candida causes one-third of vaginitis cases, and is one of the most common genital infections seen in clinical practice.[42]Sobel JD. Vaginal infections in adult women. Med Clin North Am. 1990 Nov;74(6):1573-602.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2246954?tool=bestpractice.com

[43]Yano J, Sobel JD, Nyirjesy P, et al. Current patient perspectives of vulvovaginal candidiasis: incidence, symptoms, management and post-treatment outcomes. BMC Womens Health. 2019 Mar 29;19(1):48.

https://www.doi.org/10.1186/s12905-019-0748-8

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30925872?tool=bestpractice.com

Candida species are present in about 20% to 50% of vaginal flora of healthy asymptomatic women. VVC is common in adults, especially pre-menopausal women. VVC is less common in post-menopausal and peri-menopausal patients. The global annual prevalence of recurrent VVC has been reported to be 3871 per 100,000 women.[44]Denning DW, Kneale M, Sobel JD, et al. Global burden of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018 Nov;18(11):e339-47.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30078662?tool=bestpractice.com

VVC is not considered an STI.

Candida albicans is the most common cause of VVC. Candida glabrata and Candida parapsilosis can cause VVC with milder symptoms. Symptomatic disease occurs due to a complex interplay between host inflammatory response and yeast virulence factors. Two-thirds of women who self-diagnose VVC and self-treat are found not to have VVC.[45]Ferris DG, Nyirjesy P, Sobel JD, et al. Over-the-counter antifungal drug misuse associated with patient-diagnosed vulvovaginal candidiasis. Obstet Gynecol. 2002 Mar;99(3):419-25.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11864668?tool=bestpractice.com

Risk factors for VVC include diabetes mellitus, broad-spectrum antibiotics that inhibit growth of normal vaginal flora, high oestrogen levels (e.g., when using combined hormonal contraception, menopausal hormone therapy, or during pregnancy), immunosuppression (including patients with HIV, in whom it is associated with a higher incidence and persistence of disease), and genetic susceptibility.[9]Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. Jul 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/toc.htm

[46]De Leon EM, Jacober SJ, Sobel JD, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for vaginal Candida colonization in women with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. BMC Infect Dis. 2002 Jan 30;2:1.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11835694?tool=bestpractice.com

[47]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Candida - female genital: what are the risk factors? July 2022 [internet publication].

https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/candida-female-genital/background-information/risk-factors

VVC is not related to number of recent sexual partners but may be related to increased frequency of intercourse.[48]Eckert LO, Hawes SE, Stevens CE, et al. Vulvovaginal candidiasis: clinical manifestations, risk factors, management algorithm. Obstet Gynecol. 1998 Nov;92(5):757-65.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9794664?tool=bestpractice.com

VVC can be classified as uncomplicated or complicated.[9]Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. Jul 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/toc.htm

[38]Sherrard J, Wilson J, Donders G, et al. 2018 European (IUSTI/WHO) International Union against sexually transmitted infections (IUSTI) World Health Organisation (WHO) guideline on the management of vaginal discharge. Int J STD AIDS. 2018 Nov;29(13):1258-72.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30049258?tool=bestpractice.com

[49]Sobel JD, Faro S, Force RW, et al. Vulvovaginal candidiasis: epidemiologic, diagnostic, and therapeutic considerations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998 Feb;178(2):203-11.

https://www.ajog.org/article/S0002-9378(98)80001-X/abstract

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9500475?tool=bestpractice.com

Uncomplicated VVC:

Sporadic or infrequent VVC

Mild to moderate symptoms

Likely to be C albicans species

Presence in an immunocompetent patient

Complicated VVC:

Recurrent VVC (4 or more episodes of symptomatic VVC in <1 year, with 2 episodes confirmed by microscopy or culture when symptomatic (at least one must be culture)[50]Saxon Lead Author GDGC, Edwards A, Rautemaa-Richardson R, et al. British Association for Sexual Health and HIV national guideline for the management of vulvovaginal candidiasis (2019). Int J STD AIDS. 2020 Oct;31(12):1124-44.

Includes patients with severe VVC, non-albicans candidiasis, uncontrolled diabetes, immunodeficiency, or immunosuppressive therapy

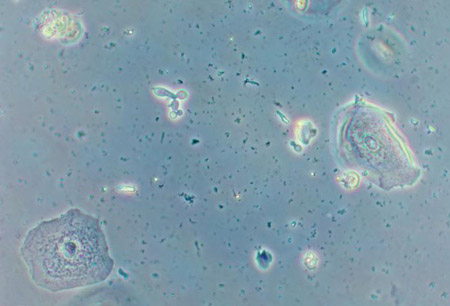

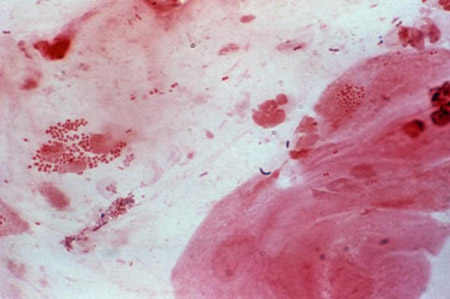

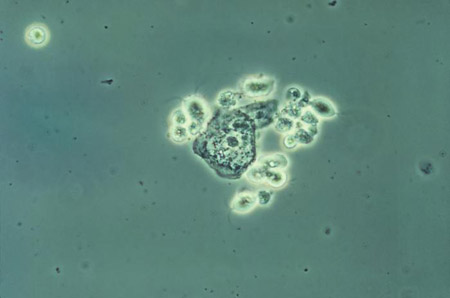

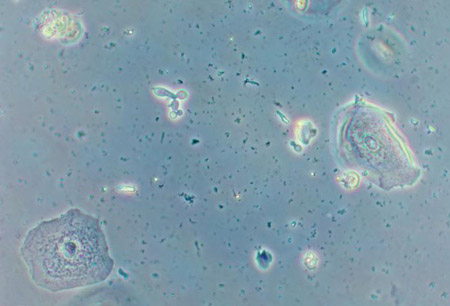

Complicated VVC is characterised by an increased incidence of candida species other than C albicans in patients with HIV and patients with recurrent candidiasis[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Vaginal smear identifying Candida albicans using a wet mount technique CDC Image Library; Dr Stuart Brown [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Vaginal smear identifying Candida albicans using Gram stain technique CDC Image Library; Dr Stuart Brown [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Vaginal smear identifying Candida albicans using Gram stain technique CDC Image Library; Dr Stuart Brown [Citation ends].

Mycoplasma genitalium

M genitalium is associated with cervicitis and pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) in women. Symptoms include vaginal discharge, dysuria, or symptoms of PID (abdominal pain and dyspareunia), but asymptomatic infection is common.[9]Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. Jul 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/toc.htm

[51]Jensen JS, Cusini M, Gomberg M, et al. 2021 European guideline on the management of Mycoplasma genitalium infections. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022 May;36(5):641-50.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35182080?tool=bestpractice.com

Transmission of M genitalium is through direct mucosal contact.

European guidelines recommend testing for M genitalium in women with:[51]Jensen JS, Cusini M, Gomberg M, et al. 2021 European guideline on the management of Mycoplasma genitalium infections. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022 May;36(5):641-50.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35182080?tool=bestpractice.com

symptoms and signs of M genitalium (mucopurulent cervicitis, intermenstrual or post-coital bleeding, dysuria with no known other aetiology, acute pelvic pain and/or PID)

on-going sexual contacts of persons being treated for M genitalium infection.

Before termination of pregnancy, testing may be considered.[51]Jensen JS, Cusini M, Gomberg M, et al. 2021 European guideline on the management of Mycoplasma genitalium infections. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022 May;36(5):641-50.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35182080?tool=bestpractice.com

US guidelines recommend that women with recurrent cervicitis should be tested for M genitalium, and that testing should be considered among women with PID.[9]Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. Jul 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/toc.htm

European and US guidelines recommend that:[9]Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. Jul 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/toc.htm

[51]Jensen JS, Cusini M, Gomberg M, et al. 2021 European guideline on the management of Mycoplasma genitalium infections. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022 May;36(5):641-50.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35182080?tool=bestpractice.com

current sex partners of M. genitalium-positive patients should be tested

all M genitalium-positive tests should be followed up with macrolide resistance testing, when available.

Less common infectious causes

Other, less common infectious causes of vaginitis include chlamydial infection, gonorrhoeal infection, herpes simplex virus, streptococcal infection, genital schistosomiasis (reported in Africa), and Entamoeba gingivalis infection (associated with intrauterine device use).[52]Sobel JD. Vaginitis. N Engl J Med. 1997 Dec 25;337(26):1896-903.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9407158?tool=bestpractice.com

[53]Verstraelen H, Verhelst R, Vaneechoutte M, et al. Group A streptococcal vaginitis: an unrecognized cause of vaginal symptoms in adult women. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011 Jul;284(1):95-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21336834?tool=bestpractice.com

[54]Yirenya-Tawiah D, Amoah C, Apea-Kubi KA, et al. A survey of female genital schistosomiasis of the lower reproductive tract in the Volta basin of Ghana. Ghana Med J. 2011 Mar;45(1):16-21.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3090093

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21572820?tool=bestpractice.com

[55]Foda AA, El-Malky MM. Prevalence of genital tract infection with Entamoeba gingivalis among copper T 380A intrauterine device users in Egypt. Contraception. 2012 Jan;85(1):108-12.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22067807?tool=bestpractice.com

[56]Bradbury RS, Roy S, Ali IK, et al. Case report: cervicovaginal co-colonization with Entamoeba gingivalis and Entamoeba polecki in association with an intrauterine device. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2019 Feb;100(2):311-3.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6367611

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30526733?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: McCoy cell monolayer micrograph revealing intracellular Chlamydia trachomatis inclusion bodies; magnified 50x CDC; Dr E. Arum, Dr N. Jacobs [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Micrograph of polymorphonuclear leukocytes and (extracellular) diplococci on a cervical smearCDC Image Library; Joe Miller [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Micrograph of polymorphonuclear leukocytes and (extracellular) diplococci on a cervical smearCDC Image Library; Joe Miller [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cervicitis and vaginal discharge due to gonorrhoeaCDC Image Library [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cervicitis and vaginal discharge due to gonorrhoeaCDC Image Library [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cervicitis due to herpes simplex virus; erosive inflammation with accompanying paracervical purulency is seenCDC; Dr Paul Wiesner [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cervicitis due to herpes simplex virus; erosive inflammation with accompanying paracervical purulency is seenCDC; Dr Paul Wiesner [Citation ends].

Non-infectious causes

Include allergy or contact dermatitis (e.g., latex, sperm, douching, dyes), chemical irritants (e.g., soaps, tampons, pads, condoms), inadequate hygiene, GSM (oestrogen deficiency), foreign body (e.g., tampons, pessary, combined hormonal rings), erosive lichen planus, postpuerperal atrophic vaginitis, desquamative inflammatory vaginitis (chronic and intractable vaginitis associated with purulent and copious discharge), pelvic irradiation, Behcet's syndrome (inflammation of the vasculature; symptoms include sores and painful swollen joints), graft versus host disease, and genital tract cancer.[52]Sobel JD. Vaginitis. N Engl J Med. 1997 Dec 25;337(26):1896-903.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9407158?tool=bestpractice.com

[57]Rodrigues AC, Teixeira R, Teixeira T, et al. Impact of pelvic radiotherapy on female sexuality. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012 Feb;285(2):505-14.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21769555?tool=bestpractice.com

[58]Bradford J, Fischer G. Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis: differential diagnosis and alternate diagnostic criteria. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2010 Oct;14(4):306-10.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20885157?tool=bestpractice.com

A complication of intravaginal slingplasty can include purulent and offensive vaginal discharge from mesh erosion.[59]Baessler K, Hewson AD, Tunn R, et al. Severe mesh complications following intravaginal slingplasty. Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Oct;106(4):713-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16199626?tool=bestpractice.com

In April 2019, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) prohibited sales and distribution of surgical mesh intended for transvaginal repair of anterior compartment prolapse (cystocele).[60]US Food and Drug Administration. Urogynecologic surgical mesh implants. Aug 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/implants-and-prosthetics/urogynecologic-surgical-mesh-implants

In October 2022, the FDA published a statement maintaining that these devices do not have a favourable benefit-risk profile.[61]US Food and Drug Administration. FDA's activities: urogynecologic surgical mesh. Oct 2022 [internet publication].

https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/urogynecologic-surgical-mesh-implants/fdas-activities-urogynecologic-surgical-mesh

In the UK, the use of surgical mesh/tape for urogynaecological prolapse, where the mesh is inserted through the vaginal wall, is currently restricted while an independent review takes place. In July 2018, NHS England advised that the use of vaginally inserted surgical mesh for pelvic organ prolapse should be postponed if it is clinically safe to do so.[62]NHS Improvement and NHS England. Vaginal mesh: high vigilance restriction period. Provider Bulletin. 11 Jul 2018 [internet publication].

https://bsug.org.uk/budcms/includes/kcfinder/upload/files/47560_embargoed-to-00-01-10-july-2018-mesh-letter-to-acute-ceos-and-mds.pdf

[63]NHS Improvement and NHS England. Extension of pause on the use of vaginal mesh. 29 Mar 2019 [internet publication].

http://www.scottishmeshsurvivors.com/pdf/MESH_letter_-_Extension_of_pause_on_the_use_of_vaginal_mesh_29_March_2019.pdf

[64]Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Pause on the use of vaginally inserted surgical mesh for stress urinary incontinence. Jul 2018 [internet publication].

https://www.gov.uk/government/news/pause-on-the-use-of-vaginally-inserted-surgical-mesh-for-stress-urinary-incontinence

[65]NHS Resolution. Vaginal mesh: what is a vaginal mesh implant? Oct 2022 [internet publication].

https://resolution.nhs.uk/vaginal-mesh/#toc-item-2

Other less common causes of vaginal discharge reported in the literature include prolapsing fibroid and vaginal fistula.[66]Sanfilippo JS, Wakim NG. Bleeding and vulvovaginitis in the pediatric age group. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1987 Sep;30(3):653-61.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3308254?tool=bestpractice.com

[67]McGreal S, Wood P. Recurrent vaginal discharge in children. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2013 Aug;26(4):205-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22264471?tool=bestpractice.com

Paediatric

Compared with the vagina of a woman of reproductive age, the vagina of a pre-pubertal patient is:

of neutral pH, without antibodies to protect it from infection

shorter and closer to the rectum

exposed to much lower oestrogen levels

For these reasons, this age group is at increased risk for vulvovaginitis (which accounts for approximately 60% to 70% of all gynaecological complaints in the paediatric population).[66]Sanfilippo JS, Wakim NG. Bleeding and vulvovaginitis in the pediatric age group. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1987 Sep;30(3):653-61.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3308254?tool=bestpractice.com

[67]McGreal S, Wood P. Recurrent vaginal discharge in children. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2013 Aug;26(4):205-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22264471?tool=bestpractice.com

[68]Gao H, Zhang Y, Pan Y, et al. Patterns of pediatric and adolescent female genital inflammation in China: an eight-year retrospective study of 49,175 patients in China. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1073886.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10506404

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37727603?tool=bestpractice.com

[69]Eyk NV, Allen L, Giesbrecht E, et al. Pediatric vulvovaginal disorders: a diagnostic approach and review of the literature. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2009 Sep;31(9):850-62.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19941710?tool=bestpractice.com

Vaginal discharge in this age group is usually not caused by infection, and almost never caused by a malignancy.[70]Jaquiery A, Stylianopoulos A, Hogg G, et al. Vulvovaginitis: clinical features, aetiology, and microbiology of the genital tract. Arch Dis Child. 1999 Jul;81(1):64-7.

https://adc.bmj.com/content/81/1/64.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10373139?tool=bestpractice.com

Causes of vaginal discharge in young girls include foreign body (45%), sexual abuse (18%), and unknown diagnosis (36%).[71]Striegel AM, Myers JB, Sorensen MD, et al. Vaginal discharge and bleeding in girls younger than 6 years. J Urol. 2006 Dec;176(6 Pt 1):2632-5.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17085178?tool=bestpractice.com

[72]Simon DA, Berry S, Brannian J, et al. Recurrent, purulent vaginal discharge associated with longstanding presence of a foreign body and vaginal stenosis. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2003 Dec;16(6):361-3.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14642957?tool=bestpractice.com

Other causes comprise non-specific vaginitis (irritation from bubble baths, perfumed soaps, tight-fitting clothes, back-to-front wiping, poor wiping after toilet training), streptococcal vaginitis (accompanies or follows a symptomatic streptococcal pharyngitis), and physiological changes (endogenous hormones 6-12 months before menarche).

Infectious causes in paediatric patients can include pinworms, transmission of infection from mother's birth canal up to a year after birth, group A beta-haemolytic streptococci, Haemophilus influenzae, and some Gram-negative bacilli. Diagnosis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae or Chlamydia trachomatis implies sexual abuse.[73]Merkley K. Vulvovaginitis and vaginal discharge in the pediatric patient. J Emerg Nurs. 2005 Aug;31(4):400-2.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16126111?tool=bestpractice.com

Blood-stained discharge requires referral for vaginoscopy.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Trichomonasvaginitis with copious purulent discharge emanating from the cervical os CDC Image Library [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Trichomonasvaginitis with copious purulent discharge emanating from the cervical os CDC Image Library [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Vaginal smear identifying Candida albicans using Gram stain technique CDC Image Library; Dr Stuart Brown [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Vaginal smear identifying Candida albicans using Gram stain technique CDC Image Library; Dr Stuart Brown [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Micrograph of polymorphonuclear leukocytes and (extracellular) diplococci on a cervical smearCDC Image Library; Joe Miller [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Micrograph of polymorphonuclear leukocytes and (extracellular) diplococci on a cervical smearCDC Image Library; Joe Miller [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cervicitis and vaginal discharge due to gonorrhoeaCDC Image Library [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cervicitis and vaginal discharge due to gonorrhoeaCDC Image Library [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cervicitis due to herpes simplex virus; erosive inflammation with accompanying paracervical purulency is seenCDC; Dr Paul Wiesner [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cervicitis due to herpes simplex virus; erosive inflammation with accompanying paracervical purulency is seenCDC; Dr Paul Wiesner [Citation ends].