Approach

A comprehensive history and thorough physical examination are essential. Laboratory tests and imaging are used to support clinical assessment.

History and clinical evaluation

Key components of the history include:

a detailed evaluation of the pain (site, onset, character, radiation, referral, associated symptoms and signs, time course, exacerbating and relieving factors, and severity)

type and time of last meal or other oral intake (information required if surgery is indicated)

past medical and surgical history, medication use, and family history.

Site of pain

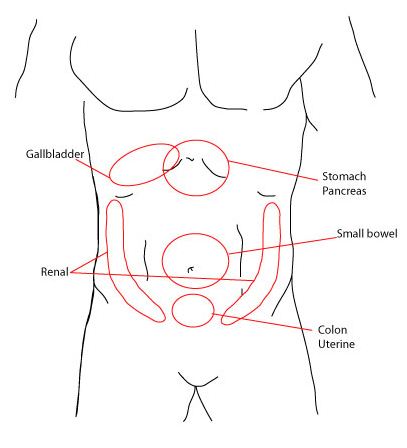

Location of pain can identify the organ involved.[28][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Common locations of visceral painCreated by the BMJ Evidence Centre [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Areas of pain that present suddenly and severe in onsetCreated by the BMJ Evidence Centre [Citation ends].

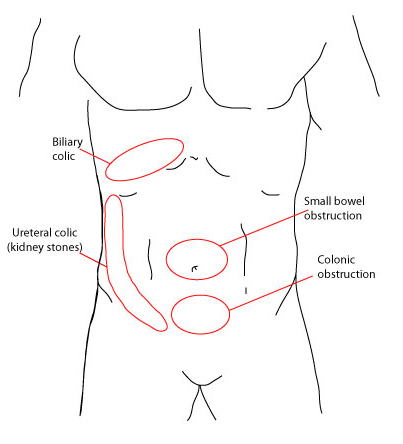

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Areas of pain that present suddenly and severe in onsetCreated by the BMJ Evidence Centre [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Areas of pain that present more colicky, crampy, and intermittent in natureCreated by the BMJ Evidence Centre [Citation ends].

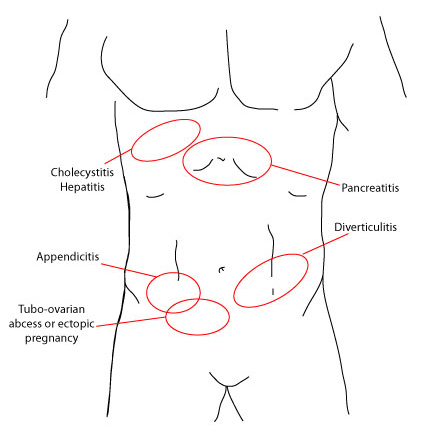

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Areas of pain that present more colicky, crampy, and intermittent in natureCreated by the BMJ Evidence Centre [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Areas of pain that present gradually or more progressivelyCreated by the BMJ Evidence Centre [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Areas of pain that present gradually or more progressivelyCreated by the BMJ Evidence Centre [Citation ends].

Epigastric pain may relate to gastric ulcer/perforation, pancreatitis, perforated oesophagus, or Mallory-Weiss tear. Cholelithiasis and myocardial infarction should also be considered.

Left upper quadrant pain may indicate splenic infarct or ruptured splenic artery aneurysm, pyelonephritis, kidney stones, or perforation or malignancy of the colon.

Right upper quadrant pain can indicate cholelithiasis, cholecystitis, hepatitis, hepatic abscess, Fitz-Hugh Curtis syndrome, perforation or malignancy of the colon, pyelonephritis, or kidney stones. It may also occur with acute appendicitis in a pregnant woman due to displacement by the enlarging uterus.

Left lower quadrant pain can indicate sigmoid volvulus (typically older patients), diverticulitis, Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis, kidney stones, gastrointestinal malignancy, psoas abscess, an incarcerated/strangulated hernia, or gynaecological concerns, including ovarian torsion or cyst rupture, ectopic pregnancy, or pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). Although uncommon, situs inversus and midgut malrotation should be considered for patients with left-sided abdominal pain.[29]

Right lower quadrant pain can indicate appendicitis, kidney stones, gastrointestinal malignancy, psoas abscess, an incarcerated/strangulated hernia, or gynaecological concerns, including ovarian torsion or cyst rupture, ectopic pregnancy, or PID.

Periumbilical pain can indicate appendicitis (may radiate to the right lower quadrant) or acute mesenteric ischaemia. Other causes of central abdominal pain include leaking or ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm and small bowel obstruction.

Persistent lateralised pain is more likely to indicate a condition associated with ascending or descending colon, kidney, gallbladder or ovary.

Perforated viscus may cause generalised pain.

Onset and time course of pain

Elicit the time of onset, whether the pain was sudden or gradual, and how it is changing over time. Sudden onset pain is typical of perforated ulcer, oesophageal tear or rupture, nephrolithiasis, biliary colic, acute cholecystitis, pancreatitis, and appendicitis. Bowel obstruction is often preceded by intermittent pain. Diverticulitis usually causes persistent pain. Previous instances of similar pain suggest a recurrent condition, such as cholecystitis, pancreatitis, or diverticulitis, with increasing frequency and severity indicating disease progression.

Character of pain

Elicit whether pain is intermittent, sharp, dull, achy, or piercing. Sharp, localised pain usually indicates that the parietal peritoneum is irritated. Dull, poorly localised pain felt in the midline is characteristic of visceral pain.

The pain of kidney/ureteric stones as they pass down the ureter is characteristically severe, with the patient unable to find a comfortable position. The pain from adhesions and incarcerated/strangulated hernias can be described as intermittent and colicky. With abdominal aortic dissection the pain can be described as severe, sharp, or tearing in the thorax or abdomen.

Radiation and referral of pain

The presence and pattern of radiation can suggest potential aetiology.[28] For example, the pain of renal colic frequently radiates from the flanks downwards into the groin.

Pain with radiation to the back can indicate pancreatitis, abdominal aortic dissection, or ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm.

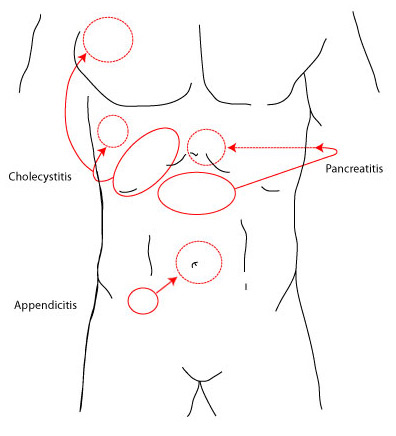

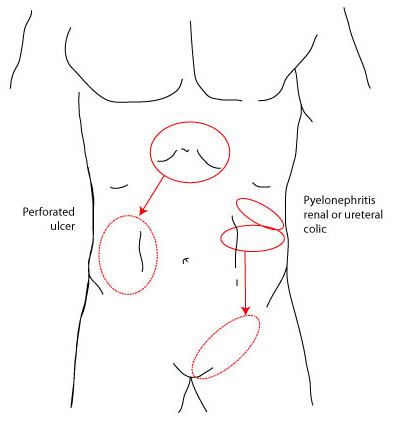

Classic locations for referred pain and its cause are as follows:[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Solid circles represent the primary sites of pain and dotted circles represent the areas of referred painCreated by BMJ Knowledge Centre [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Solid circles represent the primary sites of pain and the dotted circles represent the areas of referred painCreated by the BMJ Evidence Centre [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Solid circles represent the primary sites of pain and the dotted circles represent the areas of referred painCreated by the BMJ Evidence Centre [Citation ends].

Right scapula pain: gallbladder disease, liver disease, or irritation of right hemidiaphragm (e.g., right lower lobe pneumonia)

Left scapula pain: cardiac disease, gastric disease, pancreatic disease, splenic disease, or irritation of left hemidiaphragm

Scrotal or testicular pain (usually pain is radiating from either costophrenic angle to the groin): kidney stones or ureteral disease.

Associated gastrointestinal or systemic symptoms

Anorexia is associated with appendicitis but may also be associated with other causes of acute abdomen, including obstructive processes, diverticulitis, hepatic abscess, radiation enteritis, and infectious colitis.

Fever, chills, nausea, and vomiting are associated more commonly with cholecystitis, a ruptured duodenal ulcer, gastric ulcer, appendicitis, acute mesenteric ischaemia, PID, acute diverticulitis, hepatic abscess, hepatitis, abdominal wall haematoma, or spider bites.

Patients with an obstructive process may not have had a recent bowel movement or be able to pass flatus, although bowel motility may continue distal to the obstructed site. Enquire as to the nature of recent stool: diarrhoea, hard stool, acholic (pale) stool, or presence and appearance of blood and/or mucus.

Presence and nature of exacerbating or relieving factors

Check whether the patient has taken any medications or made any other attempts to alleviate symptoms.

The pain associated with cholecystitis and cholelithiasis can be exacerbated by eating, especially eating fatty food.

Pain caused by appendicitis can be exacerbated by movement.

Pain made worse by food suggests a gastric ulcer.

Pain relieved by eating that worsens after a few hours suggests duodenal ulcer.

Medical and surgical history

Prior surgery increases the likelihood of an obstruction secondary to adhesions.

Consider whether the patient may be immunocompromised.

History of inflammatory bowel disease: this may help to differentiate the likely cause of pain; for example, colitis due to inflammatory bowel disease.

Explore whether there has been any history of trauma in recent days or weeks. This may include obvious instances, such as from a motor vehicle accident or assault, to more innocuous falls.

For women, the date of their last menstrual period, contraception used, and current pregnancy status should be determined:

patients with a known or suspected early pregnancy are at risk for an ectopic pregnancy, particularly if they have not had an ultrasound confirming the location of the pregnancy.

Cardiovascular disease can predispose to aortic aneurysm.

Atrial fibrillation can predispose to mesenteric ischaemia.

Medication history

Any analgesia or other non-prescription medication taken for symptoms, and its effect.

Any immunosuppressive medication, radiation exposure, or chemotherapy.

Any regular opioid use or dependence (withdrawal can cause acute abdominal pain).

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs increase the risk of gastric ulceration.

Drugs that can trigger pancreatitis, e.g., corticosteroids, oestrogen, sulfonamides, tetracycline.

Social history

Excessive alcohol consumption is a risk factor for pancreatitis.

Travel history: ask about visits to areas endemic for amoebiasis (hepatic abscess), or areas that have insanitary conditions (gastroenteritis and infectious colitis).

Environmental or occupational history consistent with heavy metal exposure.

Family history

In patients with suspected gastroenteritis, check whether other family members have similar symptoms.

A positive family history may raise suspicion for nephrolithiasis, inflammatory bowel disease, hereditary Mediterranean fever, or acute intermittent porphyria.

Physical examination

Measure vital signs: blood pressure, temperature, and pulse rate.

The physical examination should be performed in the order:

Inspection

Auscultation

Percussion

Palpation

Other important examinations: rectal, pelvic, scrotal.

Inspection

Make a general assessment of how ill the patient appears.

A patient in pain and moving around unable to find a comfortable position is characteristic of renal colic; a patient who is still and reluctant to move is more typical of peritonitis; the presence of abdominal scars may give clues to previous and current pathology and the likelihood of adhesions.

The contour of the abdomen may indicate generalised distension or local bulges that may accompany bowel obstruction, hernia, or mass.

Skin changes, particularly over hernia sites, can signify strangulation with blanching erythema, discoloration, or even ulceration in late stages. Periumbilical discoloration (Cullen's sign) or bruising of the flanks (Grey-Turner's sign) indicates haemorrhagic pancreatitis.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cullen sign (periumbilical discoloration) in a 36-year-old man who presented with a 4-day history of severe epigastric pain following an alcoholic bingeCourtesy of Herbert L. Fred MD and Hendrik A van Dijk [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Grey-Turner sign (bruising of the flanks) in a 40-year-old woman with worsening epigastric pain of 5 days’ durationCourtesy of Herbert L. Fred MD and Hendrik A. van Dijk [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Grey-Turner sign (bruising of the flanks) in a 40-year-old woman with worsening epigastric pain of 5 days’ durationCourtesy of Herbert L. Fred MD and Hendrik A. van Dijk [Citation ends].

Auscultation of chest and abdomen

Small or large bowel obstruction: if examined early in the course of obstruction, there may be hyperactive 'tinkling' bowel sounds; if the patient presents later in the course of obstruction there may be reduced or absent bowel sounds, often in combination with a markedly distended abdomen.

Bowel sounds may be absent in a patient with a perforated viscus, haemoperitoneum, or other conditions with peritoneal inflammation.

Chest auscultation may reveal increased vocal resonance and reduced breath sounds consistent with pneumonia, or reduced heart sounds and/or a pericardial rub associated with pericarditis, that may be giving rise to the symptoms of an acute abdomen.

Palpation

A rigid abdomen is a hallmark sign for an acute abdomen and implies severe peritoneal irritation with reflex involuntary guarding. It is generally only encountered with perforated peptic ulcer (with generalised release of gastric acid).

Rebound tenderness (or more generally examination evidence of peritoneal irritation) is present not only with appendicitis and diverticulitis but also with any condition where there is irritation of the parietal peritoneum. It can also be seen in advanced obstruction and volvulus.

Occasionally, patients report abdominal pain to try to obtain opioid analgesia. If this is suspected, subtle distraction of the patient during examination can be useful in helping to determine the validity and severity of abdominal signs.

Murphy's sign (right upper quadrant tenderness with arrest of inhalation during palpation) may be present with cholecystitis.

A palpable and irreducible hernia may be detected in patients with incarcerated hernia. The groin should be examined in all patients with symptoms or signs of bowel obstruction.[30] Palpable masses may also be detected in patients with cholecystitis, appendix mass, intussusception, or aortic aneurysm (pulsatile).

Psoas sign, Rovsing's sign, pain on coughing, or pain on hopping are highly specific, but not sensitive, for paediatric appendicitis.[31]

Percussion

If percussion induces pain, peritoneal inflammation may be present. Also used to detect the presence of shifting dullness.

Rectal examination

Blood may be present in a range of conditions responsible for acute abdomen: acute diverticulitis; volvulus; intussusception (often mixed with mucus, often described as 'currant jelly'). It may also be detected in other conditions that may not present as an acute abdomen such as haemorrhoids, upper gastrointestinal bleeding, or lower gastrointestinal tumours.

May also reveal faecal impaction, tumour, prostate, or pelvic abscess.

Pelvic examination

Indicated for most women if the pain is in the lower abdomen.

May assist in the diagnosis of ovarian torsion, an ectopic pregnancy, or PID, or may exclude these conditions.

In PID, cervical motion tenderness and adnexal tenderness will be present, and bimanual examination may reveal a tubo-ovarian abscess.

With ectopic pregnancy, there is often a palpable adnexal mass with or without tenderness, and vaginal bleeding on speculum examination.

Ovarian torsion can cause severe, unilateral adnexal tenderness and an adnexal mass that is often palpable.

Scrotal/testicular examination

Inspect and palpate the scrotum and testicles. Tenderness can signify epididymitis or testicular torsion. Early urology consult is important as the longer the testicle is torsed the less likely that it can be salvaged.

Inguinal hernia examination is important, as some inguinal hernias can track down into the scrotum through a patent processus vaginalis. Both inguinal canals should be examined even though a hernia may present on only one side.

Diagnostic accuracy may be improved by using algorithms or decision tools, although further prospective studies are required to fully evaluate their clinical use. The Appendicitis Inflammatory Response (AIR) score and the Pediatric Appendicitis Risk Calculator (pARC) have been shown to help stratify risk of appendicitis in patients presenting with acute abdominal pain.[32][33]

Laboratory tests

Laboratory tests are often non-specific and are used to support clinical findings and medical expertise.

Initial tests to order for all patients:

Full blood count: leukocytosis is often (but not invariably) present in conditions such as appendicitis, cholecystitis, PID, duodenal and gastric ulcer, acute mesenteric ischaemia, intussusception, hepatic abscess, pyelonephritis, strangulated hernia, pancreatitis, diverticulitis, and infectious colitis.

Serum electrolytes panel that includes sodium, potassium, chloride, bicarbonate, urea, creatinine, and glucose: hypochloraemia and hypokalaemia may occur in the latter stages of intestinal obstruction; glucose may be elevated in pancreatitis if insulin secretion is compromised; serum urea may be elevated in patients with abdominal aortic dissection or aneurysm if the renal arteries are compromised.

Urinalysis: useful to identify possible urinary infection (pyelonephritis) and rule out renal or urinary source of pain (e.g., kidney stone). Also likely to have abnormal results in uraemia.

Pregnancy test for all women of reproductive age. Important in ruling out ectopic pregnancy and if considering treatments.[25]

If diagnosis is not definitive from the physical examination and/or laboratory analysis, the following tests may be helpful:

Comprehensive metabolic panel: with liver function tests (aminotransferases, bilirubin, and alkaline phosphatase).

C-reactive protein: non-specific marker of inflammation.

Coagulation studies: carried out in patients with suspected vascular causes of abdominal pain (including aortic dissection, ruptured aortic aneurysm, or acute mesenteric ischaemia), and in unstable patients, especially if surgery is indicated.

Serum lipase and amylase levels: significantly elevated levels are the hallmark of acute pancreatitis (threshold is more than 3 times normal); use serum lipase testing in preference to serum amylase.[34][35] Serum lipase levels remain elevated for longer (up to 14 days after symptom onset vs. 5 days for amylase).[36] About one quarter of people with acute pancreatitis fail to be diagnosed as having acute pancreatitis with serum amylase and serum lipase tests. It is, therefore, important to have a low threshold for admitting and treating patients whose symptoms are suggestive of acute pancreatitis, even if these tests are normal.[36][37] About 1 in 10 patients without acute pancreatitis may be wrongly diagnosed as having acute pancreatitis with these tests.[36] [

]

It is important to consider other conditions that may require urgent surgery even if these tests are abnormal.[36] Serum amylase levels may also be modestly elevated in other conditions such as ectopic pregnancy, intestinal obstruction, and perforated duodenal ulcer, although amylase levels are not used to diagnose or monitor these conditions.

]

It is important to consider other conditions that may require urgent surgery even if these tests are abnormal.[36] Serum amylase levels may also be modestly elevated in other conditions such as ectopic pregnancy, intestinal obstruction, and perforated duodenal ulcer, although amylase levels are not used to diagnose or monitor these conditions.Serum lactic acid levels: elevated in acute mesenteric ischaemia. The exact level depends on the severity of ischaemia, and the laboratory used. Serial measurement may help as a guide for resuscitation.

Assessment for colorectal cancer: the US and UK guidelines report risk thresholds for testing symptomatic patients.[38][39][40] The US guidelines recommend adults aged <50 years with colorectal bleeding symptoms undergo colonoscopy or evaluation sufficient to determine a bleeding cause.[38] The UK guidelines recommend certain quantitative faecal immunochemical tests (FITs) to guide referral for suspected colorectal cancer in adults:[39][40]

aged 40 years and over with unexplained weight loss and abdominal pain

aged under 50 years with rectal bleeding and unexplained abdominal pain

aged 50 years and over with unexplained abdominal pain.

Refer to guidelines for an exhaustive list of signs and/or symptoms that may prompt assessment for colorectal cancer.[38][39][40]

Imaging

Imaging tests are guided by findings from the history and physical examination. Radiographic examination can include:

Plain abdominal x-ray:

Often performed but rarely changes management. May be the initial imaging test in suspected bowel obstruction or constipation; a positive result may make subsequent imaging unnecessary.[41]

May reveal radiopaque gallstones, renal stones, or pancreatic stones.

Abdominal wall calcification may indicate the presence of an abdominal aortic aneurysm. Loss of the psoas shadow may be noted in the presence of aortic aneurysm rupture.

Erect chest x-ray if perforation is suspected:

Primarily performed to rule out the presence of free air under the diaphragm secondary to a ruptured viscus.

If free air is visible, this may preclude the need for additional studies - urgent surgical consultation is recommended.

May also be a useful preoperative test for anaesthetists and is often performed in conjunction with plain abdominal x-rays.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Abdominal free gas pockets, x-rayScience Photo Library; used with permission [Citation ends].

Computed tomography (CT) of abdomen:

Useful for the evaluation of almost all causes of abdominal pain, including obstruction, diverticulitis, pancreatitis, acute appendicitis, intestinal ischaemia, and abdominal aortic aneurysm.[41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50] [

]

]

Intravenous contrast is usually given, because it increases the range of detectable pathologies.[41] The patient's renal function and risk of contrast-induced acute kidney injury should be considered before intravenous contrast is administered.[51]

CT angiography is recommended for suspected cases of mesenteric ischaemia.[41]

Non-contrast CT is performed if renal stones are suspected. One retrospective study found that non-contrast CT is accurate for the clinical triage of patients older than 75 years who attend the emergency department with acute abdominal pain.[52]

May have a role in pregnancy if ultrasound findings are non-diagnostic/equivocal and magnetic resonance imaging is unavailable.[41]

Ultrasound:

Useful for helping diagnose a number of acute abdomen pathologies.[44][49][50][53][54][55]

Usually the first-line imaging test in pregnant women because it does not involve ionising radiation and is not associated with any fetal adverse effects.[56]

Ultrasound of the right upper quadrant in patients with suspected cholecystitis can reveal features such as gallstones, a thickened gallbladder wall (>4 mm), and pericholecystic fluid.[50] However, the diagnosis of chronic cholecystitis is difficult on anatomical imaging. The gallbladder may appear contracted or distended, and pericholecystic fluid is usually absent.[57]

Pelvic ultrasound in women with an ectopic pregnancy can reveal blood or a pseudogestational sac in utero, or complex mass in adnexa.[58]

Doppler ultrasound may reveal reduced or absent blood flow into a torsed ovary.

Ultrasound can also indicate presence and size of an abdominal aortic aneurysm and the presence of fluid or blood within the peritoneum; this bedside test can be helpful in assessing unstable patients where transfer for CT might be hazardous.

The focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) is a limited ultrasound examination directed solely at identifying the presence of free intraperitoneal or pericardial fluid and is used principally in trauma situations.[59]

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI):

Has a comparatively limited role in the evaluation of acute abdominal pain. It may be diagnostic for an aortic dissection and can be helpful in the assessment of pancreatitis, Crohn's disease, endometriosis, and psoas abscess.

MRI is highly sensitive and specific for the diagnosis of appendicitis in children.[49][60] Paediatric MRI may, however, require anaesthesia.

Useful second-line imaging test in pregnant women, particularly those with suspected appendicitis. Gadolinium contrast crosses the placenta and should not be used in pregnancy.[56]

Fluoroscopy:

Contrast enema using air or water is used as a diagnostic and therapeutic procedure for suspected intussusception. It can also diagnose volvulus.

Endoscopy:

Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, and colonoscopy permit direct visualisation of the gastrointestinal tract mucosa and acquisition of histological specimens.

Colonoscopy (and/or FIT) is indicated for a patient with suspected colorectal cancer. Refer to guidelines for an exhaustive list of signs/symptoms suggestive of colorectal cancer.[38][39][40]

Endoscopy is particularly useful in the investigation of suspected gastric and duodenal ulcers, inflammatory bowel disease, and malignancy.

Laparoscopy

May be considered in patients with the following characteristics:[4][5][6]

Clinically stable

No indication for therapeutic surgical intervention

No apparent cause for their abdominal pain after non-invasive procedures

No relative or absolute contraindication to surgery.

Laparoscopy may also be considered for premenopausal women or women of childbearing age with non-specific abdominal pain and suspected appendicitis. In these patients laparoscopy is associated with a higher rate of specific diagnoses being made, a lower rate of removal of normal appendices compared with open appendicectomy only, and shorter hospital stays.[61]

Laparoscopy can be both diagnostic and therapeutic (e.g., acute cholecystitis, perforated duodenal or gastric ulcer, appendicitis, lysis of adhesions).

There are data to suggest that early laparoscopy is better than active observation in establishing a final diagnosis of non-specific abdominal pain after accident and emergency admission, but the lack of uniform information does not allow it to be recommended for use in routine clinical practice.[62]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer