Approach

The evaluation of infertility focuses on identifying specific pathophysiologies. Female aetiologies reported by women undergoing assisted reproductive technology (ART) procedures include tubal factor (10.4%), ovulatory dysfunction (14.3%), diminished ovarian reserve (26.9%), endometriosis (6.5%), and uterine factors (5.8%). Male aetiologies are reported in 27.8% of ART cycles.[10] Male evaluation with at least a semen analysis is necessary while evaluating the female partner.

History

A complete medical and social history can reveal many infertility risk factors and provide focus for the remainder of the diagnostic workup. Pointers for female infertility include: age >35 years; irregular or no menses; history of sexually transmitted disease or other inflammatory pelvic process, including previous surgery (associated with tubal dysfunction); pelvic pain, including dyspareunia (associated with endometriosis or adenomyosis); very high or low body fat (linked to ovulatory disorders); or cigarette use (which may accelerate menopause). Occupational or other chemical exposure should also be considered.[63]

It is important that the history includes a thorough review of past medical illnesses (particularly childhood illnesses) that may have had an impact on ovarian function, including auto-immune disease (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus, inflammatory bowel disease), obesity, or cancer.[48][77][78] Chemotherapy or pelvic radiotherapy for cancer can cause iatrogenic primary ovarian insufficiency.[79] Psychiatric history is also important as several dopaminergic medications used to treat psychiatric diseases can suppress hypothalamic-pituitary function and increase prolactin.[52] Women seeking fertility treatment may have a higher prevalence of current or past eating disorders, which can impact fertility and subsequent pregnancy outcomes.[53] Surgical history may reveal risk factors for tubal disease, particularly pelvic surgery or appendectomy. Social history should include past history of sexually transmitted infection, past and current substance misuse, and the frequency and timing of intercourse.

Menstrual history is the best evidence of normal ovulatory function.[80] A normal menstrual cycle ranges from 21-35 days in length and menstrual bleeding occurs for 3-7 days. In a woman younger than 35 years of age, a history of a regular menstrual cycle is highly correlated with the presence of ovulation. This association is strengthened when menses are accompanied by monthly moliminal symptoms including breast tenderness, bloating, and/or mood changes. A long cycle is often associated with anovulation. By contrast, a short cycle may be associated with anovulation, inadequate follicular phase leading to poor endometrial development, or luteal phase deficiency. Some evidence suggests that a short cycle within the normal range (21-27 days) may be a sign of ovarian ageing.[81]

Dyspareunia, due to restricted uterus movement from peri-uterine adhesions, may be a presenting symptom suggesting tubal disease, endometriosis, or other anatomical causes of infertility.

Physical examination

Presenting signs may include very high or very low body fat (as indicated by body mass index, suggesting possible ovulatory dysfunction), galactorrhoea, hirsutism, and/or acne. Pelvic examination may reveal abnormal shape and mobility of the uterus, the presence of nodularity in the cul de sac (suggesting endometriosis), and/or the presence of adnexal masses or tenderness.

Assessment of ovulation

The first step is to establish whether the woman is ovulating. A history of monthly menstrual cycles with premenstrual symptoms is indicative of ovulation. Women with regular cycles do not routinely require additional tests to confirm ovulation, but they may be considered in women with hirsutism or when menstrual history is indeterminate.[2][80]

Luteal-phase progesterone is a retrospective test of ovulation. Serum is assessed 7 days after the presumed day of ovulation (or 7 days before the presumed menstrual cycle). A progesterone value >9.5 nmol/L (>3 ng/mL) is indicative of an ovulatory cycle. The timing of this test is critical.[80] The use of peak values has low sensitivity and specificity. However, any elevation of progesterone concentration in the luteal phase is suggestive of ovulation, and thus further sampling (earlier in a shorter cycle, through to menses in a longer cycle) is often done, if the first value is indeterminate. Demonstration of an elevation in serum progesterone is considered confirmatory.

Ovulation can be detected prospectively and accurately with urinary luteinising hormone (LH) prediction kits. This test uses an enzyme-linked immunoassay against the beta sub-unit of LH. LH rises abruptly for approximately 18 hours before it peaks, and ovulation typically occurs about 36 hours after the onset of the surge. Because the hormone needs to be conjugated before it is excreted, urinary LH will predict ovulation approximately 24 hours in advance. These tests are more accurate at predicting/demonstrating ovulation than basal body temperature charting (no longer recommended in the UK by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence), calendar calculation, or observation of vaginal or cervical discharge changes.[82] Additionally, this provides a prospective assay of ovulation that also can be used to time intercourse.

Basal body temperature has been historically used as a means of determining ovulation because progesterone production from the corpus luteum raises core body temperature by approximately 0.3°C (0.6°F) providing a 'biphasic' pattern of temperature. While couples may have already undertaken such assessment at home, it is not a reliable test of ovulation and is cumbersome to undertake effectively. Since there are better assessments of ovulation, it is no longer recommended and couples can be discouraged from persisting with it.

Serial ultrasound can be used to document follicular growth and ovulation.[2] However, because serial measurements are required, this is expensive and time prohibitive as an initial diagnostic tool. It is commonly used by physicians to assess ovulation in patients who are taking infertility medications while in a treatment cycle.

Endometrial biopsy cannot discriminate between fertile and infertile women and should not be a routine part of the infertility evaluation.[2][83]

If ovulation is not confirmed, further diagnostic tests are indicated to establish the cause. These include assessment of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and LH (hyper-gonadotrophic or hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism), oestrogen levels, free testosterone (polycystic ovary syndrome or other causes of hyper-androgenism), serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (thyroid dysfunction), testing for coeliac disease, prolactin (pituitary tumour), possible karyotype in the case of elevated gonadotrophins (Turner’s syndrome) or recurrent pregnancy loss (Robertsonian translocation), and other secondary investigations to elucidate a cause.

Anatomical assessment

As an extension to physical examination, a transvaginal ultrasound scan (TVUS/S) is often undertaken in the clinic setting. A TVUS/S enables the assessment of pelvic organs, including the ovaries, for evidence of follicular development, antral follicle count, polycystic appearance or the presence of significant cysts including endometriomas. It also enables the assessment of ovarian mobility/accessibility for oocyte retrieval if ultimately indicated. A TVUS/S will also enable the assessment of the uterine structure (although this may require further clarification), including congenital abnormalities (such as uterine septum), the presence of fibroids, adenomyosis, and endometrial polyps. Sizeable hydrosalpinges, indicating tubal pathology, can also be detected. Thus, a TVUS/S informs the decision for further detailed pelvic assessment.

Assessment of the structural integrity of the reproductive tract is essential to the evaluation of fertility and necessary for all individuals. This can consist of radiological imaging or surgical evaluation.

Historically, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was the preferred method of assessment for uterine abnormalities, predominantly Müllerian duct anomalies. MRI is reported to have high diagnostic accuracy for visualising uterine abnormalities (100% specificity and 80% to 100% sensitivity for the evaluation of pelvic anomalies).[84][85] The production of images in multiple planes makes MRI an excellent preoperative assessment before reproductive gynaecological surgeries such as myomectomy or metroplasty. More recently, three-dimensional (3D) ultrasound has emerged as the imaging tool of choice for the assessment of the female pelvis. A 3D ultrasound scan enables a more detailed evaluation of the uterus, with reconstruction of anatomical planes, elusive to conventional TVUS/S.[86] Uterine assessment with 3D ultrasound is cost effective, non-invasive and highly acceptable to women. Furthermore, it also has equivalent, if not higher, diagnostic accuracy to MRI, especially if used by experienced clinicians.[87]

The assessment of tubal patency is commonly undertaken in an outpatient setting. Chlamydia antibody testing may be considered as an initial, non-invasive test to assess the risk for tubal occlusion.[2] A negative result suggests a low risk for tubal occlusion, but it does not rule out occlusion due to other infections. A positive result should be followed by further evaluation of tubal patency.[2][80] Women who are not at risk of tubal obstruction because of comorbidities such as pelvic inflammatory disease, a previous ectopic pregnancy or endometriosis can be offered hysterosalpingography (HSG); those with comorbidities should be offered laparoscopy with chromopertubation or hysteroscopy.[1][80]

HSG is performed by injecting radio-opaque dye into the uterus and following the dye with fluoroscopy. Uterine abnormalities are outlined by the dye, and tubal obstruction is noted by the absence of free-spill into the peritoneal cavity. According to one individual patient data meta-analysis, HSG has a pooled sensitivity of 53% and a pooled specificity of 87% for identification of any tubal pathology.[88]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Normal hysterosalpingography (HSG)From the collection of Dr Jared C. Robins [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Hysterosalpingography (HSG) demonstrating bilateral hydrosalpingesFrom the collection of Dr Jared C. Robins [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Hysterosalpingography (HSG) demonstrating bilateral hydrosalpingesFrom the collection of Dr Jared C. Robins [Citation ends].

Because the positive predictive value of HSG is low, results suggesting tubal obstruction might require further evaluation.[80]

A similar screening technique, hysterosalpingo-contrast sonography (HyCosY), uses TVUS in combination with a reflective medium injected transcervically to give a view of the endometrial cavity, as well as an assessment of tubal integrity.[89] HyCosY has a pooled sensitivity of 93% (95% CI 90% to 95%) and a pooled specificity of 90% (95% CI 87% to 92%) for the assessment of tubal patency.[90] Although this imaging modality is more reliant on trained technicians, it has the advantage of avoiding radiation exposure, thereby gaining preference over HSG. Use of an oil-soluble contrast media for tubal flushing in the assessment of tubal patency may increase clinical pregnancy rates, and it is recommended over water-soluble contrast media.[2][91][92] The most common complication of oil-soluble contrast HSG is intravasation.[93] Oil embolism is a rare complication, but the technique should be performed with fluorescence guidance.[2]

Saline-infusion sonography (SIS) can be used to follow up intrauterine abnormalities seen on HSG or evaluate the uterus if there is no suspicion about the fallopian tubes. Traditional ultrasonography is not sensitive enough to determine whether lesions are intracavitary, because the uterus is a potential space. Injecting saline into the uterus to provide a sonographic window within the endometrial cavity enables better visualisation. The sensitivity and specificity of SIS were both estimated to be 100% when surgery was used as a definitive test.[94][95]

Although radiological imaging provides information about the viscous portions of pelvic structures, it provides little information about peri-tubal adhesions or endometriosis. Furthermore, patients with risk factors, such as previous pelvic infections, are not suitable candidates for invasive imaging in an office setting. Laparoscopy is the gold standard investigation to further this diagnostic work-up. The decision to perform laparoscopy as an initial diagnostic modality is based on clinical suspicion. For example, in a woman with a history of cyclic pelvic pain suggestive of endometriosis, laparoscopy may be the best initial evaluation. In selected cases, hysteroscopy at the time of laparoscopy may be indicated (e.g., to clarify uterine abnormalities or assess submucous fibroids). Hysteroscopy has a pooled sensitivity and specificity of 88% and 85%, respectively, for detection of tubal obstruction.[96]

In addition to direct visualisation for diagnostic purposes, laparoscopy and hysteroscopy may also confer the benefit of surgical treatment at the same time. Some evidence suggests that hysteroscopy may improve live birth rates in women undergoing assisted reproductive technology, even when initial imaging is normal.[97][98] However, one Cochrane review noted that results were inconclusive when only considering trials at low risk of bias, and guidelines recommend against hysteroscopy when imaging is normal.[2][99]

[  ]

[Evidence C]

]

[Evidence C]

Some physicians perform a post-coital test to assess the cervix and cervical mucus. However, there is high intra-observer variation in this test, and it is no longer recommended for routine use.[2][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Normal hysterosalpingography (HSG)From the collection of Dr Jared C. Robins [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Hysterosalpingography (HSG) demonstrating bilateral hydrosalpingesFrom the collection of Dr Jared C. Robins [Citation ends].

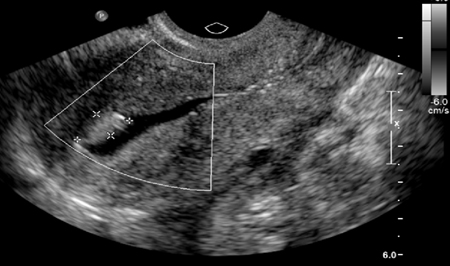

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Hysterosalpingography (HSG) demonstrating bilateral hydrosalpingesFrom the collection of Dr Jared C. Robins [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Normal saline infusion ultrasoundFrom the collection of Dr Jared C. Robins [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Normal saline infusion ultrasoundFrom the collection of Dr Jared C. Robins [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Saline infusion ultrasound with polypFrom the collection of Dr Jared C. Robins [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Saline infusion ultrasound with polypFrom the collection of Dr Jared C. Robins [Citation ends].

Ovarian reserve testing

Age is the best predictor of fertility.[12][13] Many researchers have sought to establish assays of 'ovarian ageing' to assess the quality and quantity of the remaining oocytes in an attempt to predict reproductive potential.[100] The most commonly used tests are the measurement of basal FSH on day 2-5 of the menstrual cycle (levels >10 IU/L may be considered consistent with diminished ovarian reserve and levels >8.9 IU/L may be considered predictive of a low response to future ovarian stimulation), a total antral follicle count undertaken by TVUS on day 3 of the menstrual cycle (<5-7 oocytes may be considered consistent with diminished ovarian reserve and ≤4 oocytes may be considered predictive of a low response to future ovarian stimulation), and measurement of anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), which is not cycle-day specific (<7.1 pmol/L [<1 ng/mL] may be considered consistent with diminished ovarian reserve and ≤5.4 pmol/L [≤0.76 ng/mL] may be considered predictive of a low response to future ovarian stimulation).[1][80][101]

[  ]

]

Basal FSH and oestradiol can be measured together in the early follicular phase to assess ovarian reserve; however, oestradiol (E2) should not be measured in isolation to predict the outcome of fertility treatment.[1][80] Elevated oestradiol levels may suppress FSH levels, so the value of measuring oestradiol levels is that they provide context for normal FSH levels. High oestradiol levels are, therefore, associated with reproductive ageing and diminished ovarian reserve.

Most studies suggest that abnormal basal hormonal levels are predictive of response to fertility medication, but not highly predictive of pregnancy or failure to conceive, especially in young women.[102] So-called dynamic ovarian reserve testing (e.g., clomifene challenge) confers little additional benefit.[103] Ovarian reserve testing may be useful for patients with unexplained infertility or for those at risk of ovarian failure. Examples of risks for ovarian failure include age older than 35 years, family history of primary ovarian insufficiency, history of ovarian surgery, or smoking.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer