History and exam

Key diagnostic factors

common

presence of risk factors

Risk factors strongly associated with inherited haemophilia include: family history of haemophilia (family history from the maternal side usually positive), and male sex.

history of recurrent or severe bleeding

Spontaneous or trauma-induced bleeding in joints and muscles; excessive bleeding after surgery, dental procedures, or trauma (onset may be delayed by several days); recurrent nasal/oral mucosa bleeding; easy bruising; gastrointestinal bleeding; haematuria.

bleeding into muscles

Musculoskeletal bleeding is the hallmark of haemophilia.

Presents with pain and swelling of the involved area, commonly extremities, with decreased range of motion, erythema, and increased local warmth.

May occur in any muscle, including, but not limited to, the quadriceps, hamstrings, iliopsoas, biceps, and triceps.

Bleeding into the iliopsoas may present as severe lower abdominal, upper thigh, and/or lower back pain. Patients have pain on extension, but not on rotation, of the hip joint and typically have a characteristic gait (flexed hip, inward rotation). There may be paraesthesia in the medial thigh and signs of femoral nerve compression (e.g., loss of the patellar tendon reflex, quadriceps weakness). Urgent treatment is required.

Large bleeding into the deep flexor muscle group within a closed space in the extremities may result in compartment syndrome with neurovascular compromise. This is a musculoskeletal emergency.

prolonged bleeding following heel prick or circumcision

Typical presentation in neonates with severe haemophilia.

Bleeding occurs in about 50% of newborns with haemophilia who undergo circumcision.[26]

mucocutaneous bleeding

Minor mucocutaneous bleeding, such as epistaxis, bleeding from gums following minor dental procedures, and easy bruising, is common.

Severe bleeding following trauma, surgery, or dental procedures is also commonly described.

haemarthrosis

Musculoskeletal bleeding is the hallmark of haemophilia.

Presents with swelling of the joints (commonly knees, elbow, and ankles) with associated pain, decreased range of motion, and increased warmth. Haemarthrosis may not be associated with these classical physical signs if it presents soon after onset.

Bleeding typically occurs in a single joint, but occasionally multiple joints may be involved.

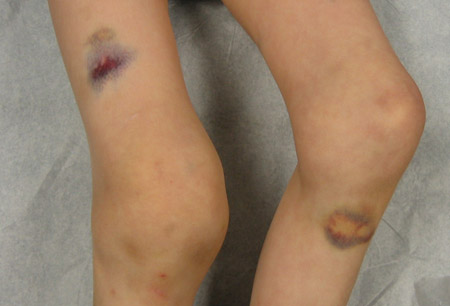

Recurrent haemarthrosis causes chronic joint damage with associated joint contractures and deformities.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Acute haemarthrosis of the right knee with ecchymosisPediatric Hematology Department, University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bilateral acute haemarthroses of the kneesPediatric Hematology Department, University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bilateral acute haemarthroses of the kneesPediatric Hematology Department, University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Massive swelling due to acute haemarthrosis of the right kneePediatric Hematology Department, University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Massive swelling due to acute haemarthrosis of the right kneePediatric Hematology Department, University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston; used with permission [Citation ends].

uncommon

pseudotumour

A potentially limb- and life-threatening condition. The 'tumour' grows as a chronic, encapsulated cystic mass subsequent to inadequate management of recurrent bleeds in soft tissue/muscles or bones.[60] Often occurs in muscle adjacent to bone, which can be secondarily involved.

The pseudotumour can become massive, causing pressure on adjacent vital organ(s) and neurovascular structures and may cause pathological fractures. Management should be coordinated between haemophilia specialists and the orthopaedic surgeons.

intracranial bleeding

About 3% to 5% of newborn boys with severe haemophilia present with intracranial haemorrhage.[27][28][29][30]

Symptoms and signs are not specific, but include hypoactivity, decreased oral intake, irritability, bulging/tense fontanelle, seizures, and pallor.

Signs and symptoms in older children include hypoactivity, irritability, headache, vomiting, seizures, and focal neurological deficits.

In adulthood, other medical conditions may increase the risk of intracranial bleeding (e.g., uncontrolled hypertension).

Other diagnostic factors

common

excessive bruising/haematoma

Skin involvement consistent with bruises or haematomas.

Common sites are the lower extremities.

fatigue

Symptom of iron deficiency anaemia; common only if significant bleeding has occurred.

menorrhagia and bleeding following surgical procedures or childbirth (female carriers)

Most common presentation in women and girls who are carriers of congenital haemophilia, particularly those with clotting factor levels in the haemophilia range.[25]

extensive cutaneous purpura (acquired haemophilia)

Main manifestation in patients with acquired haemophilia. Unlike in the congenital form, bleeding into the joints is not a prominent feature in these patients.

uncommon

gastrointestinal bleeding and haematuria

May occur spontaneously or following trauma.

May occur in any age group and with any severity, although it is more common in older patients.

When present in children, it is commonly associated with trauma to the abdomen or lower back.

distended and painful abdomen

Caused by intra-abdominal bleeding and may occur at any age.

When present in children, it is commonly associated with trauma to the abdomen or lower back, although spontaneous presentations are seen.

pallor, tachycardia, tachypnoea, or hypotension

Signs of anaemia; common only if significant bleeding has occurred.

Risk factors

strong

family history of haemophilia (congenital haemophilia)

Specific genetic mutations are causal in congenital haemophilia.[11][12][19][20][21]

Two-thirds of patients have a family history of haemophilia. For those patients without a family history, the carrier status of the mother should be ascertained by molecular testing to facilitate counselling.

Spontaneous mutations may account for a lack of positive family history for haemophilia.

Patients within a given family carry the same genetic mutation.[22][23][24]

About 50% of severe haemophilia A cases are due to intrachromosomal inversions involving intron 1 or 22 of the factor VIII gene.[13]

The remaining cases are due to other genetic alterations such as deletions, insertions, missense or nonsense point mutations, or abnormal splicing.

Most cases of haemophilia B are due to point mutations and deletions.

male sex (congenital haemophilia)

Congenital haemophilia has an X-linked recessive pattern of inheritance.[9]

Boys and men are almost exclusively affected, due to X-linked pattern of inheritance.

Female carriers may have clotting factor levels in the haemophilia range and require appropriate haemophilia management.

There are rare cases of girls and women with severe haemophilia.

age >60 years (acquired haemophilia)

Although haemophilia is usually an inherited disorder, a much rarer acquired form may occur. Acquired haemophilia typically occurs in older people and should be suspected and investigated in older adults who present with a prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time and/or new bleeding symptoms.[3]

autoimmune disorders, inflammatory bowel disease, diabetes, hepatitis, pregnancy and postnatal period, malignancy, monoclonal gammopathies, use of certain drugs (acquired haemophilia)

Occasional occurrence in pregnancy and the postnatal period may account for small peak in incidence in the 20- to 30-year-old age group.[3]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer