Approach

The evaluation of pericardial effusion entails:

Diagnosing pericardial effusion with clinical history and examination; confirmed by imaging

Assessing the haemodynamic significance of the effusion

Determining aetiology by clinical assessment, imaging, and laboratory investigations.

Clinical assessment

The following signs and symptoms should prompt further evaluation for pericardial effusion:

Otherwise unexplained chest discomfort, pleuritic pain, and dyspnoea.[16] Acute pericarditis typically causes sharp, pleuritic chest pain, which is improved by sitting up and leaning forwards and exacerbated by coughing and lying supine.[6] The pain may radiate to the trapezius ridge which, like the pericardium, is innervated by the phrenic nerve.[58]

Patients who have any systemic disorder known to involve the pericardium and a raised jugular venous pressure.[5]

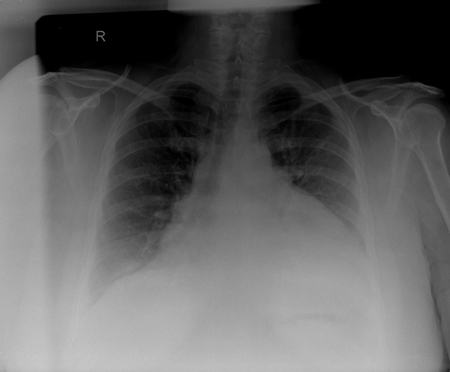

Unexplained cardiomegaly without pulmonary congestion on chest x-ray.[5]

Chest pain and/or haemodynamic instability after recent blunt trauma to the chest, cardiac surgery, or cardiac intervention.

Cardiac arrest with pulseless electrical activity or asystole.

Timing

Onset of symptoms is typically subacute. Symptoms may develop acutely if effusion is related to trauma, free wall rupture, iatrogenic causes, or aortic dissection.

Associated symptoms

Patients with viral pericarditis often have an abrupt onset of symptoms and other features of a viral illness, such as cough and sore throat. A low-grade fever is common, but a fever >38°C (>100°F) is not typical and should prompt consideration of bacterial pericarditis.

Symptoms suggesting tuberculosis include fever, night sweats, weight loss, fatigue, cough, and haemoptysis.

Fatigue, arthralgia, photosensitive rash, alopecia, and oral ulcers suggest systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).[59]

Cold intolerance, fatigue, constipation, decreased memory, dry skin, weight gain, depression, oligomenorrhoea or amenorrhoea, and reduced scalp and body hair may occur in hypothyroidism.

Past medical history

Previous myocardial infarction (MI). Pericardial effusion following MI (post-myocardial infarction syndrome or Dressler's phenomenon) is a rare complication that can occur in the weeks or months following an MI.

Recent cardiac surgery or intervention. Post-cardiac surgery effusion occurs in up to 85% of patients.[60] These patients are also at higher risk of bacterial pericarditis.

Chronic heart failure. There may be a history of hypertension, coronary artery disease, valvular disease, or cardiomyopathy. Symptoms include dyspnoea, decreased exercise tolerance, orthopnoea, and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea.

Chronic renal failure, particularly if the patient is dependent on dialysis. These patients are also at higher risk of bacterial pericarditis. Symptoms of uraemia include nausea, vomiting, and mental status changes.

History of malignancy, particularly lung cancer, breast cancer, haematological malignancies, and mesothelioma. Metastatic infiltration of the pericardium and radiotherapy can cause pericardial effusion.

Secondary amyloidosis can develop in patients with chronic inflammatory conditions, such as bronchiectasis, osteomyelitis, and rheumatoid arthritis.

Pericardial effusions may occur in severe hypothyroidism.

Immunosuppression increases susceptibility to bacterial, fungal, and tuberculous pericarditis.

Drug history

Hydralazine, procainamide, and isoniazid are the most common drugs identified as a cause of drug-induced lupus erythematosus.[56]

Chemotherapy drugs such as anthracyclines, cyclophosphamide, cytarabine, all-trans retinoic acid, and immune checkpoint inhibitors are all associated with pericardial effusion.[14]

Pericardial effusion may occur in patients with ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome following administration of injectable gonadotrophins.[54]

Examination

Physical examination may be normal if the patient does not have haemodynamic compromise.

Examination findings suggestive of pericardial effusion include:

Pericardial friction rub: a high-pitched scratching sound best heard over the left sternal border with the patient leaning forwards at end-expiration.[6] Rubs may be 1, 2, or 3 parts, corresponding to the periods of greatest heart movement in the cardiac cycle. The pericardial friction rub may also be transient, and thus it is useful to examine patients suspected of pericarditis on multiple occasions.

Distant heart sounds with a quiet precordium is a common finding in pericardial effusion.

Pulsus paradoxus: a decrease in systolic blood pressure during inspiration of >12 mmHg has a sensitivity of 98% and a specificity of 83% for the detection of tamponade.[61]

In cardiac tamponade, the accumulating pericardial effusion has a restrictive effect on the filling of the heart, which results in a more pronounced and interdependent respiratory variation in the right and left ventricular filling and an inspiratory drop of the systolic arterial pressure of 10 mmHg or more.

To measure pulsus paradoxus, the blood pressure cuff is inflated above systolic blood pressure. The cuff is deflated slowly, listening for the first Korotkoff sound, which will be intermittent and heard during quiet expiration. The difference (in mmHg) between this first Korotkoff sound and the pressure at which a Korotkoff sound is heard with each beat is the pulsus paradoxus.

Pericardial constriction may produce similar examination findings to tamponade with pulsus paradoxus and elevated jugular venous pressure. A pericardial knock may be evident during palpation and/or auscultation, and constriction is also often associated with gross liver enlargement and ascites.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Auscultation of the pericardium: to elicit pericardial rubs the patient is invited to lean forward (A) or rest on elbows and knees (B). Both physical manoeuvres aim to increase the contact of visceral and parietal pericardium.Imazio M. Pericardial involvement in systemic inflammatory diseases. Heart 2011;97:1882-92. [Citation ends].

Electrocardiography

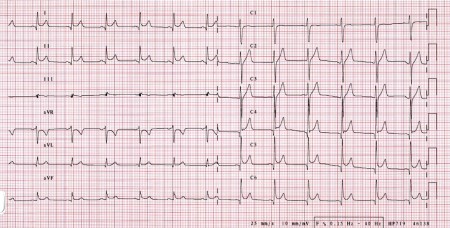

Patients with suspected pericardial effusion should have an electrocardiogram. ECG changes include:

Sinus tachycardia.

Low QRS voltage.

Electrical alternans. This occurs when the heart's swinging motion in the pericardial fluid results in beat-to-beat variation of the ventricular, and occasionally the atrial, axis on the ECG.

When inflammation involves the epicardium, such as in acute pericarditis, the ECG may show diffuse ST-segment elevation and PR depression signalling generalised epicardial injury. Up to 60% of patients with acute pericarditis have typical ECG findings.[62][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: ECG in acute pericarditis. Nearly ubiquitous ST segment elevation corresponding to ST depression in aVR (lead augmented vector right). Height of ST elevation is about 25% of height of T waves peak in V5–V6. Most PR segments are slightly depressed with respect to the T-P baseline (atrial current of injury).Imazio M. Pericardial involvement in systemic inflammatory diseases. Heart 2011;97:1882-92. [Citation ends].

Imaging

Echocardiography

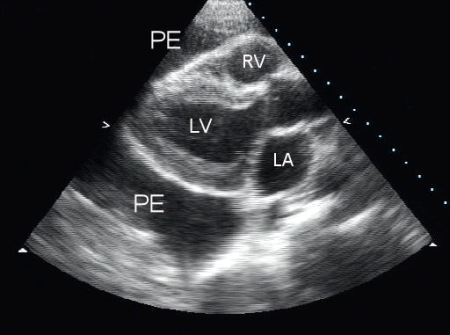

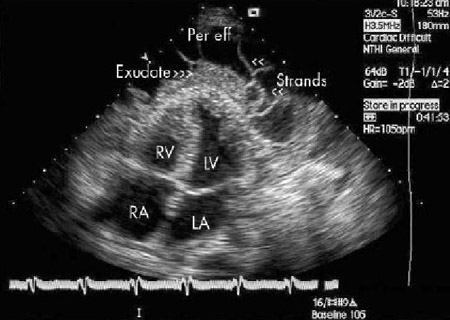

Transthoracic echocardiography is the investigation of choice for a suspected pericardial effusion. It is a non-invasive and effective diagnostic modality. As well as confirming the diagnosis, echocardiography allows the operator to evaluate the size and haemodynamic effects of the effusion.[7]

An echo-free space between the two layers of the pericardium indicates the presence of an effusion.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Parasternal long-axis view of a pericardial effusion (PE); LA = left atrium, LV = left ventricle, RV = right ventricleFrom the collection of Dr Rajdeep Khattar [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Apical 4-chamber view of a 2-dimensional echocardiogram of a patient with tuberculous pericardial effusion; LA = left atrium, LV = left ventricle, Per eff = pericardial effusion; RA = right atrium, RV = right ventricleFrom: George S, Salama AL, Uthaman B, et al. Heart. 2004; 90:1338-1339 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Apical 4-chamber view of a 2-dimensional echocardiogram of a patient with tuberculous pericardial effusion; LA = left atrium, LV = left ventricle, Per eff = pericardial effusion; RA = right atrium, RV = right ventricleFrom: George S, Salama AL, Uthaman B, et al. Heart. 2004; 90:1338-1339 [Citation ends].

General echocardiographic assessment of pericardial effusion includes:

Size

The maximum end-diastolic effusion thickness (distance between epicardial and parietal layers of the pericardium) is measured and the effusion size is graded as:

Trivial (seen only in systole)

Small (<10 mm)

Moderate (10-20 mm)

Large (>20 mm)

Very large (>25 mm)

Location

Circumferential

Loculated

Consistency

Clear

Partly organised (with strands spanning the two layers of the pericardium)

Fully organised.

Trans-oesophageal echocardiography can be helpful to diagnose loculated and complex effusions and in cases where transthoracic echocardiography is inconclusive.

Chest radiography

A chest x-ray may show a water-bottle-shaped cardiac silhouette with a distinct pericardial fat stripe, suggesting a large pericardial effusion. Pleural effusions may also be present. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CXR in a patient with a pericardial effusion showing typical findings of a water-bottle-shaped cardiac silhouette with a distinct, fat, pericardial fat stripeFrom the collection of Dr Rajdeep Khattar [Citation ends].

Computed tomography

Transthoracic echocardiography has limited spatial resolution and cannot reliably visualise the pericardium, unless there is pronounced thickness (>5 mm; normal thickness of 0.5 to 1.0 mm). Cardiac computed tomography (CT) has higher spatial resolution and is therefore more reliable in detecting an abnormally thickened pericardium (defined as >2 mm). It can provide quantitative and qualitative information on pericardial effusion and is the most sensitive imaging modality to detect pericardial calcification.

Owing to its high spatial resolution, cardiac CT is most helpful in providing anatomical information and for the planning of pericardiotomy or surgical drainage of loculated or complex effusions. High attenuation fluid suggests haemopericardium, particularly in cases of trauma, post-surgical effusion, or aortic dissection. Nodularity of the pericardium may indicate malignancy.[63] CT angiography is the preferred test to diagnose aortic dissection in haemodynamically stable patients.

Magnetic resonance imaging

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the most comprehensive modality to assess the pericardium.[6][64][65][66] It allows qualitative and quantitative assessment of pericardial effusion.

Transudative pericardial effusions appear dark on T1-weighted sequences; exudative effusions are of low to medium intensity on T1 and medium to bright on T2-weighted sequences.[66][67][68] Haemorrhagic effusions are bright on T1- and T2-weighted sequences, but they can evolve to a chronic haematoma (>15 days) with low signal intensity.[66][67] Proteinaceous effusions are bright on T1-weighted sequences.[66][67]

Cardiac MRI can detect abnormally thickened pericardium on T1-weighted black-blood sequences (<4 mm is considered normal), and constrictive physiology (e.g., respirophasic septal shift).[6][65][66][67] Delayed gadolinium enhancement can provide important information on the presence and grade of ongoing pericardial inflammation and therefore guide anti-inflammatory therapies.[65][66][67]

Note that cardiac MRI sequences are susceptible to cardiac motion artifacts that can obscure or be misinterpreted as pathology.[69]

Laboratory evaluation

In 60% of cases, a pericardial effusion is due to a known underlying disease or condition.[70] Thus, all patients require a thorough history and physical examination.

If an underlying cause is not identified, initial testing includes inflammatory markers. Raised inflammatory markers support a diagnosis of acute idiopathic pericarditis, severe effusions without inflammatory signs are associated with chronic idiopathic pericarditis, and tamponade without inflammatory signs is associated with malignancy.[70]

Initial tests

Full blood count: leukocyte count is typically mildly elevated in acute idiopathic pericarditis; a substantially elevated leukocyte count may suggest bacterial pericarditis.[58]

Serum C-reactive protein: is elevated in most cases of acute pericarditis and so may not be helpful in determining the underlying aetiology. However, it is useful for monitoring the response to treatment and is recommended for all patients with suspected acute pericarditis.[6]

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate: is often elevated in acute pericarditis.

Urea, electrolytes, and creatinine: may demonstrate uraemia in chronic kidney disease, or acute kidney injury if there is an acute infection, trauma, or lupus nephritis.

Troponin: performed to detect concomitant myocarditis. The magnitude of elevation correlates with the extent of ST-segment elevation. Levels may be in the range considered diagnostic of an acute MI in some patients. Levels return to normal within 1 to 2 weeks of diagnosis. Elevated levels do not appear to confer prognostic significance in acute pericarditis.

Coagulation studies.

Further blood tests may be indicated depending on the suspected aetiology of the effusion.

Thyroid-stimulating hormone: elevated in hypothyroidism.

Antinuclear antibody (ANA), anti-double-stranded DNA antibody, and anti-Smith antibody: suspected SLE.

Antihistone antibodies: suspected drug-induced lupus.

Serum and urine immunoglobulins: suspected amyloidosis.

Blood cultures: essential when bacterial pericarditis is suspected, to identify causative organisms. Viral cultures for cytomegalovirus may be ordered in selected immunocompromised patients. In other circumstances there is little clinical utility in ordering them, as most cases of viral pericarditis are benign and self-limiting, and a positive test would not change management.[71]

HIV: order when evidence of immunosuppression is present on examination, or the patient has risk factors for HIV infection.

Thick blood smear for microscopy: if Chagas disease is suspected.

Pericardiocentesis

Pericardial fluid sampling can include Gram and acid-fast bacilli stains and cultures, polymerase chain reaction, tuberculosis-specific testing (e.g., adenosine deaminase, lysozyme, and gamma-interferon), tumour markers, and cytology, and may be useful in the following scenarios:

Suspected purulent or tuberculous pericarditis

Suspected malignant pericardial effusion

Moderate to large pericardial effusion in patients with HIV and/or immune suppression

Moderate to large or progressive pericardial effusion in patients not responding to initial therapy and when diagnostic work-up is inconclusive.[72]

Cytological evaluation is the gold standard for diagnosis of neoplastic pericardial effusion, with a sensitivity of 71% to 92% and a specificity approaching 100%.[13]

Contrary to common practice, and unlike pleural effusion evaluation, differentiating between an exudate and transudate based on cell count, lactate dehydrogenase, and protein and glucose levels is not generally helpful for the differential diagnosis and management of patients with pericardial effusion.[73]

Pericardial biopsy

Pericardial biopsy may be considered in the course of surgical drainage, when large effusions recur without a previous diagnosis, and when tuberculous or malignant aetiologies are suspected.[6] Although the diagnostic yield is historically low and complicated by a high degree of false-negative results, recent advances in pericardioscopy, which allows direct visualisation of the pericardium, have improved the yield (40% diagnostic yield) and reduced the incidence of false-negative findings (6.7% false-negatives).[74]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer