History and exam

Key diagnostic factors

common

copious watery diarrhoea

Copious watery, bloodless 'rice-water' diarrhoea is specific for cholera in the proper clinical setting. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cup of typical 'rice-water' stool from a cholera patient shows flecks of mucus that have settled to the bottomCDC/Dr William A. Clark [Citation ends].

Diarrhoea >1 litre/hour is almost pathognomonic of cholera if sustained (>20 mL/kg during a 4-hour observation period).[74]

evidence of volume depletion

Patients with severe volume depletion in the context of a diarrhoeal illness are 5.5 times more likely to have cholera than other diarrhoeal illnesses.[88]

In mild-to-moderate volume depletion, patients may present with irritability, sunken eyes, dry mouth, evidence of a significant (>20 mmHg) postural drop in blood pressure (BP), mildly decreased skin turgor, and thirst but be able to take significant amounts of oral fluid.[3][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Due to severe volume depletion, cholera manifests itself in decreased skin turgor, which produces the so-called 'washer woman's hand' signCDC/Dr William A. Clark [Citation ends].

In severe volume depletion, patients will be lethargic or comatose with circulatory collapse (thready pulse, low BP with a systolic BP <80 mmHg), as well as sunken eyes, absent tears, dry mucous membranes, poor (>2 seconds) capillary return, and poor skin turgor.[3]

Other diagnostic factors

common

age <5 years

In endemic areas, adults often have pre-existing immunity to circulating strains of Vibrio cholerae. Therefore, new outbreaks often affect the youngest first. Because diarrhoea due to other agents is common in young children, the occurrence of severe diarrhoea in this age group is not specific for cholera.

During outbreaks, cholera can affect all ages. Even though rates are higher in children, more adults become ill because, population-wise, there are more adults at risk. Among returning travellers, adults may be affected with an incubation period of up to 5 days.

Breastfeeding has been shown to protect babies from the occurrence of cholera, probably due to the reduced likelihood of direct exposure.[36] Breastfed infants are also less likely to be hospitalised due to cholera.[42]

ingestion of shellfish

Shellfish are a common source of contamination with cholera.

family history of recent, severe, cholera-like illness

Cholera often occurs in family clusters, due either to secondary cases or to a common source outbreak.[89]

vomiting

Can be an early sign of cholera and is extremely common among children, but is non-specific.[73]

uncommon

fever

Although fever was seen in volunteer studies (38% of volunteers during the prodrome of artificial cholera infection), it is not seen in naturally acquired cholera.[51]

abdominal pain

Reported in one third of children studied.[73]

lethargy or coma

May indicate severe volume depletion with imminent cardiovascular collapse.

Risk factors

strong

ingestion of contaminated water

Vibrio cholerae freely replicates in fresh and low-salt-containing water, such as is found in river estuaries.

Contaminated water sources have been shown to be responsible for outbreaks of cholera.[26]

Evidence from South America shows that drinking untreated water and ice is a risk for cholera.[27]

Contaminated weaning products are an important risk factor for cholera in young children.[28]

Simple measures to improve the quality of water storage and treatment have been shown to be effective interventions.[29][30]

ingestion of contaminated food

Infected water can contaminate food sources. Contaminated shellfish and its products, or food handlers, can spread bacteria as food is prepared.[22]

Shellfish, clams, oysters, and crabs sustain viable Vibrio cholerae because they usually contain few competing bacteria and have a neutral or slightly alkaline pH. Rice, vegetables, and unsanitary street vendor food have also been responsible for outbreaks.[27][31]

inadequate sanitation

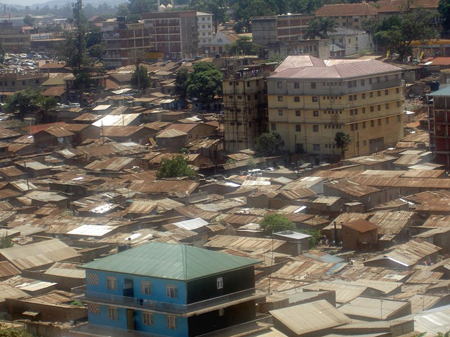

Outbreaks of cholera generally occur in low-resource settings and in areas of poverty, such as in urban slums, refugee camps, conflict zones, following natural disasters, and prisons with no or limited access to safe water and where sanitation facilities (e.g., flushing lavatories, and sewer systems). Where municipal sanitation does occur, lapses in chlorination can lead to outbreaks.[27][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Typical shanty town in Kampala, Uganda; cholera outbreaks are commonplace in low-income countriesDr Philip Gothard, Consultant Infectious Diseases Physician, Hospital for Infectious Diseases, University College London Hospital, UK [Citation ends].

People living in areas with recent flooding or in areas with poor sanitation and overcrowding are also at risk of similar circumstances, which could lead to an epidemic.

Exposure to a known cholera case, usually a family member, can also lead to secondary cases.[21][32]

Urban background, low socioeconomic status, poor personal hygiene, unsafe sanitation, and unsafe drinking water supply primarily contribute to the occurrence of epidemics.

recent heavy rains and flooding

Accounted for 25% of all outbreaks of cholera reported in the 10-year period up to 2005.[16] During periods of flooding, rates of cholera rise almost sixfold.[33]

Those most affected after flooding tend to be people using tube wells that become contaminated with faecal contents from poor-quality sanitation.

decreased gastric acid secretion

blood group O

Many infectious diseases show a relationship between blood group and disease susceptibility.[37] There is a higher risk of symptomatic cholera among individuals with blood group O.[36][38]

However, although blood group O leads to more severe disease, it may actually be protective against initial infection or colonisation.[36][39] Blood group O is much less strongly represented in areas of cholera endemicity such as South Asia, suggesting a protective effect of the blood group.[32]

malnutrition

Duration, but not volume, of diarrhoea is prolonged in 30% to 70% of those adults and children with evidence of malnutrition, as measured by height and weight.[40]

weak

HIV infection

There is some evidence that HIV infection may predispose to cholera. In a case-control study from sub-Saharan Africa, there was a trend towards HIV-positive patients having a recent history of suspected cholera.[36][41] The mechanism is likely due to the depletion of secretory immunoglobulin A, the most important antibody for mucosal immunity, due to its ability both to neutralise cholera toxin and block binding receptors used by the bacteria as they attach to the epithelium.

There is some evidence that people living with HIV might shed viable bacteria in the stool for much greater periods of time than people with normal immunity.

Other types of immunocompromise are a theoretical consideration in the context of disease, but there is no published literature.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer