Approach

A focused history is critical to establish the diagnosis and also to differentiate between primary and secondary dysmenorrhoea. A detailed clinical examination is valuable and aids in the diagnosis of the cause of secondary dysmenorrhoea.

Many myths are associated with menstrual disorders and the doctor must take a sensitive approach and provide an explanation regarding an aetiology and its management.[38][39] Treatment is often introduced prior to investigations, particularly in young women who may also require contraception. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists: contraceptive choices for young people Opens in new window

History

Should include the following:[6][40][41][42][43]

Age of menarche.

Onset of dysmenorrhoea: especially in regard to menarche. Primary dysmenorrhoea typically occurs 6-12 months after the onset of menarche. Secondary dysmenorrhoea can occur at menarche or several years after menarche. Obstructive Mullerian duct pathologies typically manifest in the first cycles with cyclical pain.

Characteristics of pain: in primary dysmenorrhoea, the pain is crampy in the lower abdomen and radiates to the back and thighs, and is usually referred to as ‘spasmodic’ pain. Secondary dysmenorrhoea may be similar or experienced as pelvic heaviness and back pain and is described as a ‘congested’ feeling.

Timing and duration of pain: primary dysmenorrhoea commences at or a few hours prior to menstruation, and subsides completely with the end of blood flow. Secondary dysmenorrhoea usually starts before the onset of the menses, increases progressively throughout the late luteal phase, and continues during menstruation.

Associated symptoms: in primary dysmenorrhoea, fatigue (85%), irritability (72%), dizziness (28%), headache (45%), lower backache (60%), diarrhoea (60%), and nausea and vomiting (89%) may be present.

Exacerbating and alleviating factors: secondary dysmenorrhoea is more commonly refractory to simple treatments such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and the combined oral contraceptive pill (COCP).

Severity of symptoms: including how they interfere with common daily activity, and how they impact on mental health e.g., low mood and anxiety.

Menstrual history: information regarding the menstrual cycle length, regularity, duration, and amount of menstrual flow should be sought. These can direct towards a secondary cause (such as uterine fibroids, polyps, or adenomyosis) because heavy menstrual bleeding is unusual in young women with primary dysmenorrhoea.

Additional symptoms: history of post coital bleeding, intermenstrual bleeding, vaginal discharge, or deep dyspareunia should be sought, as they are associated with secondary dysmenorrhoea.

Sexual history: to identify partner status and risk factors for PID, fertility aspirations and contraceptive use. Primary dysmenorrhoea seems to be more prevalent in those with a history of sexual abuse.[42][43]

Obstetric history: plans for pregnancy and a history of primary or secondary infertility should be sought.

Medical history: various conditions can mimic pain similar to dysmenorrhoea, such as irritable bowel syndrome or lactose intolerance. Associated mental health conditions are common.

Family history: any similar history in the family should be noted. Endometriosis often affects other family members.

Drug history: information regarding medications, recreational drugs, or smoking.

Physical examination

Pelvic examination is usually unremarkable in primary dysmenorrhoea and is not usually indicated in young women who are not sexually active if the symptoms are suggestive of primary dysmenorrhoea. However, a complete pelvic examination may be appropriate for sexually active and even some non-sexually active adolescents with dysmenorrhoea who do not respond to first-line therapy with NSAIDs or hormonal therapy. In these instances, a pelvic examination identifies any areas of pain and excludes abnormal anatomy or pelvic masses. The examination should include a careful inspection of the external genitalia and a speculum examination followed by a bimanual examination.

The absence of clinical findings does not exclude pathology and should be complemented with other diagnostic methods.

Findings suggestive of an underlying pathology

Endometriosis: positive findings on clinical examination, 35% to 40% of the time with adnexal, rectovaginal, and uterine tenderness, together with cervical excitation.[44] More advanced disease may present with tender nodules over the uterosacral ligaments and rectovaginal septum, unilateral or bilateral adnexal masses tender on palpation (endometrioma), and a fixed immobile uterus.

Acute or chronic pelvic inflammatory disease: bilateral lower abdominal tenderness; uterine and cervical motion tenderness on pelvic examination and presence of adnexal tenderness with or without a mass. Speculum examination, in acute cases, may reveal a vaginal or cervical discharge and appearance of cervicitis.

Uterine leiomyoma (fibroids): suggested by an enlarged mobile uterus that may be smooth or multi-nodular.

Adenomyosis: a diffusely tender and globular enlarged uterus is frequently palpable during bimanual examination.

Investigations

When the history and clinical examination are suggestive of primary dysmenorrhoea, further investigations are rarely warranted.[45]

Further investigations may be necessary in the presence of non-specific symptoms, abnormal clinical findings, treatment failure of primary dysmenorrhoea, suspicion of secondary dysmenorrhoea, or when the diagnosis is in doubt.

Imaging studies

Fibroids, adnexal pathology, endometriomas, and intrauterine contraceptive devices are best assessed with pelvic ultrasonography. Transvaginal ultrasound is preferable as it offers better resolution and the pelvis can be examined in more detail. It may also reveal the presence of tenderness. In the presence of intrauterine lesions such as polyps or submucous fibroids, the sensitivity and specificity of transvaginal ultrasound may be improved by using saline infusion sonography.

Three-dimensional (3D) ultrasound assesses organs in the coronal plane and can be superior when assessing endometrial pathology.

MRI and CT pelvis and/or abdomen may be done when the sonographic results are equivocal.

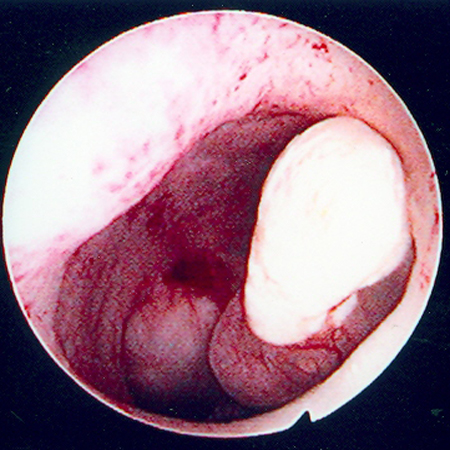

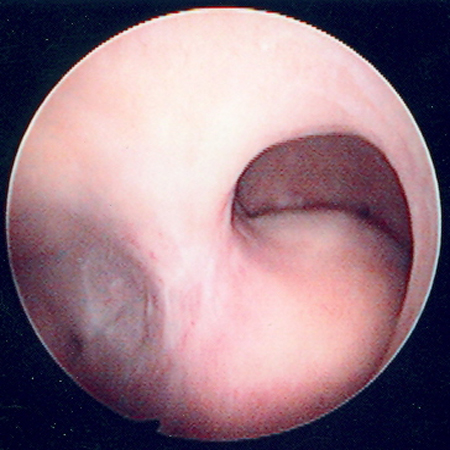

Hysteroscopy may be indicated to evaluate intrauterine pathology if the sonographic findings are unclear. In the presence of polyps or submucous fibroids, subsequent resection can be attempted.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Multiple polyps are identified on hysteroscopic examination of the uterine cavity in this patient with persistent vaginal spottingFrom the collection of Dr M.F. Mitwally and Dr R.J. Fischer; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Hysteroscopic image of a large pedunculated submucous uterine fibroidFrom the collection of Dr M.F. Mitwally and Dr R.J. Fischer; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Hysteroscopic image of a large pedunculated submucous uterine fibroidFrom the collection of Dr M.F. Mitwally and Dr R.J. Fischer; used with permission [Citation ends].

WBC, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C- reactive protein, FBC

A raised WBC count along with a high erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) can be evidence of an acute or chronic inflammatory disease. These tests are non-specific and may not always be elevated in mild disease that can be typically managed on an outpatient basis. WBC, ESR, and CRP may also be elevated in non-gynaecological conditions such as acute appendicitis.

FBC may be necessary to exclude anaemia if there is associated heavy menstrual bleeding.

Genital swabs

Chlamydia (CT), gonorrhoea (GC), and Mycoplasma genitalium(MG) may be present in the lower genital tract in women with pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), although a negative swab does not exclude the diagnosis. A combined nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) for CT/GC can be obtained from the vulvovagina (self-taken) or endocervix. Local implementation of MG testing may vary outside of specialist genitourinary medicine settings. Where direct microscopy is possible, the absence of pus cells in the vagina/endocervix has a high negative predictive value for PID (>95%).[46]

Serum or urine pregnancy test

To exclude pregnancy in all women who present with abdominal and pelvic pain and/or menstrual irregularity.

Laparoscopy

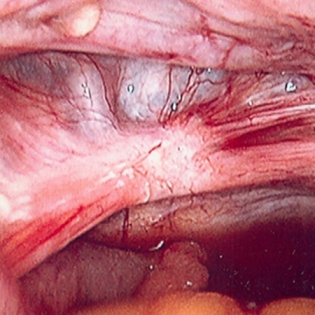

Aids in the diagnosis of endometriosis, adnexal pathology, intra-abdominal adhesions, and pelvic inflammatory disease and at the same time can offer treatment for these conditions. Nevertheless, a study has reported that 35% of laparoscopies for pelvic pain or secondary dysmenorrhoea were negative.[47][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Laparoscopic image of endometriotic noduleFrom the collection of Dr Jonathon Solnik; used with permission [Citation ends].

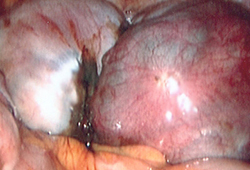

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Laparoscopic image of ovarian endometriomaFrom the collection of Dr Jonathon Solnik; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Laparoscopic image of ovarian endometriomaFrom the collection of Dr Jonathon Solnik; used with permission [Citation ends].

Tumour markers such as Ca-125

Should be checked in the presence of an ovarian mass. However, the test is non-specific and levels can be elevated in endometriosis and other conditions such as ovarian cancer.

Endometrial Pipelle biopsy

May be necessary in the presence of an abnormal bleeding pattern in women aged over 40 years.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer