Recommendations

Urgent

Subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) is an acute life-threatening condition.[38] Early diagnosis and securing the aneurysm within 48 hours are associated with a lower risk of rebleeding and lower disability rates than delayed aneurysm treatment (i.e., after 48 hours).[39][44][45]

Suspect SAH in any patient with a sudden, severe headache that peaks within 1 to 5 minutes (thunderclap headache) and lasts more than an hour.[46][47] Patients typically present with vomiting and non-focal neurological signs, which may include loss of consciousness and neck stiffness.[38]

If you suspect SAH:[38]

In the community, refer the patient immediately to emergency care

In an acute hospital setting, arrange an urgent assessment of the patient by a senior clinical decision-maker (e.g., in the UK, a consultant, staff-grade, associate-specialist, or specialty doctor).

Assess the patient's level of consciousness (use the Glasgow Coma Scale [GCS]). [ Glasgow Coma Scale Opens in new window ] [43]

In patients with GCS score ≤8 or falling, stabilise and investigate at the same time, as timely treatment can prevent complications such as rebleeding or acute hydrocephalus.

Use an ABC approach.[43]

Protect the airway with simple airway manoeuvres and adjuncts.

Monitor controlled oxygen therapy. An upper SpO2 limit of 96% is reasonable when administering supplemental oxygen to most patients with acute illness who are not at risk of hypercapnia. Evidence suggests that liberal use of supplemental oxygen (target SpO2 >96%) in acutely ill adults is associated with higher mortality than more conservative oxygen therapy.[48] A lower target SpO2 of 88% to 92% is appropriate if the patient is at risk of hypercapnic respiratory failure.[49]

Call the anaesthetist. These patients require intubation, deep sedation, and in some cases paralysis.

Use isotonic saline as fluid resuscitation to restore normovolaemia.[43]

Start with 3 L/day (isotonic/normal saline 0.9%), and adjust infusion for oral intake and supplement other electrolytes as necessary.[43]

Avoid all hypotonic fluids.

Check pupils for size, shape, and reactivity to light every 20 minutes once sedated and paralysed. Discuss any pupil changes with the neurosurgeon.

Fixed and dilated pupils in comatose patients are associated with poor prognosis, especially when present bilaterally.[50]

Order an urgent non-contrast computed tomography (CT) head scan, to be done as soon as possible for all patients with acute sudden, severe headache (thunderclap headache) or other signs and symptoms that suggest SAH.[38][39][43] Ideally, the CT scan should be within 6 hours of symptom onset.[38]

SAH is confirmed by the hyperdense appearance of blood in the subarachnoid space/basal cisterns.[43]

As soon as the diagnosis of SAH is confirmed, urgently discuss with a specialist neurosurgical centre the need for transfer of care of the patient to the specialist centre.[38]

Key Recommendations

Diagnostic confirmation

CT head scan positive: hyperdense appearance of blood in the subarachnoid space/basal cisterns confirms SAH.[39][43]

If a CT head scan performed within 6 hours of symptom onset is reported and documented by a radiologist to show no evidence of SAH, the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends:[38]

Against routinely offering a lumbar puncture (LP)

To consider alternative diagnoses and seek advice from a specialist.[38]

If a CT head scan performed more than 6 hours after symptom onset is negative or inconclusive, NICE recommends:[38][51]

To consider an LP

Waiting for at least 12 hours to pass from the onset of symptoms before performing an LP (if LP is indicated).

Diagnose a subarachnoid haemorrhage if the LP sample shows evidence of xanthochromia on spectrophotometry.[38] Consider alternative diagnoses if the LP sample shows no evidence of xanthochromia on spectrophotometry.[38]

Referral and further investigations

As soon as the diagnosis of SAH is confirmed, urgently discuss with a specialist neurosurgical centre the need for transfer of care of the patient to the specialist centre.[38]

When referring the patient to a neurosurgical unit, specify the following as these will inform management (by surgical clipping or endovascular coiling, where possible):

Time from onset of symptoms

Age

Comorbidities

Conscious level

Any neurological deficit.

Do not use a SAH severity score in isolation to determine the need for, or timing of, transfer of care to a specialist neurosurgical centre.[38][52]

Request computed tomography angiography (CTA) in patients with confirmed SAH to identify the causal pathology, define anatomy, and plan the best option to secure the aneurysm related to the haemorrhage.[38] If CTA of the head does not identify the cause of the SAH and an aneurysm is still suspected, consider digital subtraction angiography (DSA), or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) if DSA is contraindicated.[38]

SAH is an acute life-threatening condition.[38] Early diagnosis and securing the aneurysm within 48 hours are associated with a lower risk of rebleeding and lower disability rates than delayed aneurysm treatment (i.e., after 48 hours of admission).[39][43][44] Therefore, it is essential to recognise the condition quickly and be aware of the spectrum of presentation.[45]

Patients with SAH may present in different ways: from sudden severe headache without neurological signs, to collapse or seizures.[53] Other common symptoms are non-specific and include nausea, vomiting, and photophobia.

If you suspect SAH:[38]

In the community, refer the patient immediately to emergency care

In an acute hospital setting, arrange an urgent assessment by a senior clinical decision-maker (e.g., in the UK, a consultant, staff-grade, associate-specialist, or specialty doctor).

Common signs and symptoms

Sudden-onset severe headache

Severe headache that typically peaks within 1 to 5 minutes (thunderclap headache) and lasts more than an hour.[38][46][47] Headache typically presents alongside vomiting, photophobia, and non-focal neurological signs.[54]

Expert opinion is that the speed of onset is more diagnostic than the severity.[55]

Have a high index of suspicion for SAH when carrying out initial assessment of a patient with unexplained acute severe headache.[38][54]

If you suspect SAH, request an urgent non-contrast computed tomography (CT) head scan to be carried out as soon as possible.[38] This is the standard diagnostic test for SAH.[39][43]

Diagnosis is confirmed by the hyperdense appearance of blood in the subarachnoid space/basal cisterns.[43]

Practical tip

A migraine may also be described as sudden, severe headache and can also be associated with vomiting and photophobia but will usually have occurred previously. A history of migraine, however, does not preclude a non-migraine aetiology of headache, including SAH. It is often more difficult to recognise SAH in people with an explosive headache as the only complaint. SAH is the cause in 11% to 25% of patients with thunderclap headache.[56]

Depressed consciousness/loss of consciousness

Caused by blockage of the normal cerebrospinal fluid circulation by blood in the subarachnoid space.

On admission, up to two-thirds of people with SAH have a depressed level of consciousness, half of whom are in a coma.[57]

Altered consciousness is a finding that can resemble stroke (ischaemic or haemorrhagic).

Loss of consciousness is independently associated with death or poor functional outcomes at 1 year.[58]

Be aware that unconscious patients still need a neurological examination to assess reflexes, tone, and pupil changes. In patients with a Glasgow Coma Scale score ≤8 or falling: [ Glasgow Coma Scale Opens in new window ]

Check pupils for size, shape, and reactivity to light every 20 minutes

Discuss any pupil changes with neurosurgeon

Fixed and dilated pupils in comatose patients are associated with a poor prognosis, especially when present bilaterally.[50]

Practical tip

The patient's level of consciousness is the most predictive factor of outcome as it is correlated directly with the degree of neurological dysfunction at time of first presentation.[58] A poor neurological status on admission predicts cardiac abnormalities thought to be secondary to overwhelming sympathetic activation.[59][60][61][62]

Neck stiffness and muscle aches (meningismus)

A clue to diagnosis only when associated with sudden, severe headache.

The patient may have limited or painful neck flexion on examination.[38]

A finding that can resemble infective meningitis.

Photophobia

A common symptom seen in many neurological disorders, particularly in people with migraine.

In SAH, photophobia can be due to irritation of the meninges by blood in the subarachnoid space.

Nausea/vomiting

Due to irritation of the cerebral cortex caused by the haemorrhage.

Confusion

Caused by blockage of the normal cerebrospinal fluid circulation by blood in the subarachnoid space.

Other signs and symptoms

Seizures

Seizures at the onset of SAH occur in around 7% of patients.[63] About 10% of people with SAH develop seizures in the first few weeks.[64]

Associated with a large haemorrhage and subdural haematoma.[65]

Diplopia, eyelid drooping, mydriasis, orbital pain

Unilateral or bilateral sixth cranial nerve palsies can cause diplopia due to raised intracranial pressure.

Compression of the third cranial nerve by the aneurysm can cause eyelid drooping, diplopia with mydriasis, and orbital pain.

Visual loss

Intraocular haemorrhages (secondary to increased intracranial pressure) are seen in 10% to 40% of patients with SAH.[66] They cause visual loss in the affected eye, a finding that can resemble stroke (ischaemic or haemorrhagic). This is associated with worse prognosis and increased mortality.[66]

Agitation

Due to irritation of the cerebral cortex caused by the haemorrhage.

A finding that can resemble stroke (ischaemic or haemorrhagic).

Focal neurological deficits

One in every 10 patients with aneurysmal SAH presents with focal neurological deficits (e.g., unilateral loss of motor function, loss of visual field, aphasia).

Independently associated with higher in-hospital mortality rates and severe disability at discharge.[67]

These findings can resemble stroke (ischaemic or haemorrhagic).

Atypical presentations

Atypical presentations of SAH include less severe headaches, headaches accompanied by vomiting and low-grade fever, and prominent neck pain.

Suspect SAH in any patient with a history of sentinel (warning) headaches. These may represent minor hemorrhages. These headaches:[2]

Are sudden, intense, and persistent

Precede the SAH by days or weeks

Resolve by themselves

Occur in 15% to 60% of patients with spontaneous SAH.

Make sure you ask about:

The rate of onset and time to peak intensity of the headache[38]

Any features of meningeal irritation

For example, neck stiffness, photophobia, nausea, and vomiting

Any associated loss of consciousness, no matter how brief

Any family history of brain haemorrhage

Any current anticoagulant/antiplatelet agents use

Practical tip

Thorough and careful history-taking is essential. Most patients with sudden, severe headache do not have SAH. Ask if the headache is genuinely thunderclap. See SAH mimics below.

Other risk factors include the following.

Demographics

Age ≥50 years old

The median age of onset of a first SAH is 50 to 60 years.[43]

Female sex

Medical history

Hypertension

Genetic connective tissue disorders and other systemic disorders associated with aneurysm formation, or other vascular abnormalities. For example:

Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, pseudoxanthoma elasticum, neurofibromatosis type I, and polycystic kidney disease.[41]

Substance use/misuse and drug history

Smoking

Alcohol misuse

Drinking 19 units (150 g) or more of alcohol per week is associated with an increased risk of SAH (relative risk 4.7, CI 95% 2.1 to 10.5) as is sudden intake in high quantities.[34] However, the relationship of SAH to excessive alcohol use is less robust than that of hypertension or smoking.[34][40]

Cocaine use

Exposure to adrenergic or serotonergic drugs

May result in reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS), which is characterised by severe headaches, with or without other acute neurological symptoms, and diffuse segmental constriction of cerebral arteries that resolves spontaneously within 3 months. RCVS is associated with convexity subarachnoid haemorrhage, ischaemic stroke, and haemorrhagic stroke.[42]

SAH mimics

Consider other causes of thunderclap headache when history doesn’t point to SAH or investigations for SAH are negative.

Although most people with a thunderclap headache do not have SAH, this should not deter further investigation if SAH is suspected.[38]

Benign causes[75] | Non-benign causes[75] |

|

|

Perform a full neurological examination (pay special attention to pupillary reaction in unconscious patients).

Be aware that unconscious patients still need a neurological examination to assess reflexes, tone, and pupil changes. In patients with Glasgow Coma Scale score ≤8 or falling: [ Glasgow Coma Scale Opens in new window ]

Check pupils for size, shape, and reactivity to light every 20 minutes. Discuss any pupil changes with a neurosurgeon.

Fixed and dilated pupils in comatose patients are associated with poor prognosis, especially when present bilaterally.[50]

A unilateral fixed pupil with other signs of oculomotor nerve palsy in a conscious patient is more likely to represent a ruptured posterior communicating artery aneurysm than raised intracranial pressure. This does not carry the same poor prognosis as pupillary changes in unconscious patients.

Findings that resemble stroke (ischaemic or haemorrhagic) may include:

Altered consciousness

Agitation

Focal findings

Unilateral loss of motor function

Loss of visual field

Aphasia

Ocular findings

Intraocular haemorrhages resulting in visual loss

Isolated dilation of one pupil and loss of pupillary light reflex. In a patient with reduced consciousness, this may indicate brain herniation as a result of rising intracranial pressure

Oculomotor nerve impairment, which may indicate bleeding from the posterior communicating artery.

Meningismus (neck stiffness and muscle aches) can resemble infective meningitis.

Non-contrast CT head (all patients)

Order an urgent non-contrast computed tomography (CT) head scan, to be done as soon as possible, for all patients presenting with acute sudden, severe headache (thunderclap headache) or other signs and symptoms that suggest SAH.[38][39][43][51] Ideally, the CT scan should be within 6 hours of symptom onset.[38]

There is good evidence showing that non-contrast CT head scans carried out within 6 hours of symptom onset are highly accurate and can be used to rule out a diagnosis of SAH. CT head scans done more than 6 hours after symptom onset are less accurate.[38][51]

Modern, third-generation scanners detect SAH in 93% of cases if done within the first 24 hours after the bleed, and in almost 100% of cases when performed within 6 hours of onset of headache and interpreted by an experienced radiologist.[76][77][78][79] The sensitivity of CT in detecting SAH declines after the first 24 hours to 68% on day 3 and 58% on day 5 as the blood undergoes lysis.[8][9]

CT is the standard diagnostic test for SAH; the hyperdense appearance of blood in the subarachnoid space/basal cisterns confirms SAH.[43]

Practical tip

Some patients with SAH present with vomiting and/or are agitated and require anaesthesia to be scanned. Call the anaesthetist as soon as possible to avoid delaying diagnosis in these patients.

Order thin cuts (3-5 mm) to avoid missing small, thin collections of blood.

State on the CT request that SAH is being considered so that appropriately thin slices are taken and the radiologist knows what they are looking for.

Practical tip

Look for hydrocephalus on the CT. This may explain a decreased level of consciousness (low or falling Glasgow Coma Scale score).

As soon as the diagnosis of SAH is confirmed, urgently discuss with a specialist neurosurgical centre the need for transfer of care of the patient to the specialist centre.[38] See Referral below.

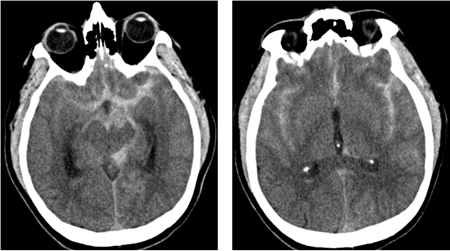

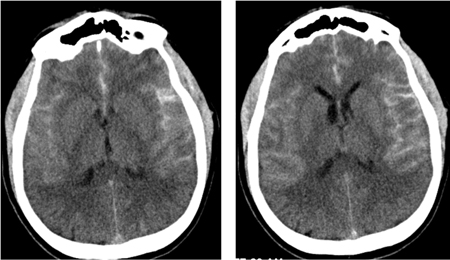

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT brain showing subarachnoid haemorrhage from a ruptured posterior cerebral artery aneurysm (1 of 2)Courtesy of Dr Salah Keyrouz; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT brain showing subarachnoid haemorrhage from a ruptured posterior cerebral artery aneurysm (2 of 2)Courtesy of Dr Salah Keyrouz; used with permission [Citation ends].

MRI head

While CT is the preferred imaging modality for confirming SAH, the European Stroke Organization states that MRI with multiple sequences is equally suitable for diagnosis within the first 24 hours.[43]

As soon as the diagnosis of SAH is confirmed, urgently discuss with a specialist neurosurgical centre the need for transfer of care of the patient to the specialist centre.[38] See Referral below.

Blood tests (all patients)

Order in all patients: full blood count (FBC), serum electrolytes, clotting profile, serum troponin I, and serum glucose.

Full blood count

Leukocytosis is often seen.

Leukocytosis following SAH is an independent risk factor for cerebral vasospasm.[80]

Serum electrolytes

Hyponatraemia is the most common electrolyte abnormality in SAH, occurring in up to 50% of patients. It is usually associated with syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH).[12] Another common cause is cerebral salt-wasting syndrome.[12]

Clotting profile

Baseline coagulation disturbances are common in SAH and need to be treated.

Coagulopathy may be present (i.e., elevated INR, prolonged PTT).

Troponin I

Elevated in 20% to 28% of patients in the first 24 hours after symptom onset, in the absence of pre-existing coronary artery disease, as a complication of acute brain injury.[59][83]

This elevation in troponin I represents an acute myocardial injury thought to be a consequence of autonomic dysregulation with sympathetic stimulation. It is an order of magnitude less than what is usually seen in the setting of myocardial infarction.[84] It is associated with an increased risk of delayed cerebral ischaemia, poor outcome, and death following SAH.[85]

Glucose

Hyperglycaemia develops in one third of SAH patients and is a feature of any acute brain injury.

It is associated with poor clinical condition on admission and independently associated with poor outcome.[43]

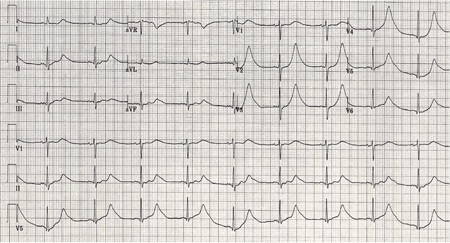

ECG (all patients)

Request an ECG in all patients. Half of patients have an abnormal ECG on admission.[86]

Consult immediately with a cardiologist about any ECG changes.

Common cardiac findings in SAH include:

Practical tip

Patients with SAH may have ECG changes that mimic acute coronary syndrome and ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Seek specialist advice when deciding whether to perform a computed tomography head scan before or after coronary angiography. Use your clinical judgement alongside specialist input to weigh up the likelihood of the patient having SAH versus acute coronary syndrome.[87]

Aneurysm rupture can lead to cardiac complications, such as left ventricular subendocardial injury and takotsubo cardiomyopathy (even in the absence of acute coronary disease) leading to treatment delays.[43] SAH can also cause cardiac arrest.[88]

Cardiac abnormalities in SAH may be due to massive catecholamine release resulting in overwhelming sympathetic activation.[59][60][61][62] As a result, transient myocardial ischaemia and failure may occur.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: ECG done on admission of a patient with subarachnoid haemorrhage; note peaked, tall T waves (1 of 2)Courtesy of Dr Salah Keyrouz; used with permission [Citation ends].

Perform continuous ECG monitoring in all patients at least until occlusion of the aneurysm.[43]

Patients with CT head scan negative/inconclusive and high suspicion for SAH

If a CT head scan performed within 6 hours of symptom onset is reported and documented by a radiologist to show no evidence of SAH, the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends:[38]

Against routinely offering an LP

To consider alternative diagnoses and seek advice from a specialist.

Note, however, that guidelines differ on this point. The European Stroke Organization recommends that lumbar puncture must be performed in any patient with clinically suspected SAH despite negative CT findings. It advises to do this 6-12 hours after symptom onset because blood degradation can take some hours.[43]

If a CT head scan performed more than 6 hours after symptom onset is negative or inconclusive, NICE recommends:[38][51]

To consider an LP

Waiting for at least 12 hours to pass from the onset of symptoms before performing an LP (if LP is indicated)

In the UK, standard practice is to perform an LP 12 hours after the onset of symptoms, or within 14 days if presentation is delayed.[39][89] This is because of the time it takes for red blood cells to lyse and for xanthochromia (elevated bilirubin) to be detected by spectrophotometric analysis of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

Collect 3 tubes of CSF labelled 1 to 3. This is standard practice in the UK.

This helps if the tap has been traumatic (i.e., bleeding from needle insertion when performing LP), as a reduction in the number of red blood cells from tube 1 to tube 3 indicates traumatic tap whereas the number of red blood cells will remain the same if the presence of blood in the CSF is due to SAH.

Practical tip

Bilirubin degrades in sunlight. Place the sample immediately in an opaque bag (brown bag). This prevents in-vitro degradation of bilirubin to deoxyhaemoglobin, which may lead to false-negative results.[89]

Exclude SAH if there is a combination of a red blood cell count less than 2000 × 106/L and no xanthochromia in a patient with traumatic lumbar puncture.[90]

Always use spectrophotometric analysis of CSF as visual inspection for xanthochromia is unreliable.[39][89]

Spectrophotometric analysis of CSF may lead to false-positive results and unnecessary investigation whereas visual inspection for xanthochromia may lead to false-negatives and missed SAH.[89] UK organisations NEQAS (National External Quality Assessment Service) and the Royal College of Physicians recommend always using spectrophotometry analysis, rather than visual inspection.[39][89] However, many countries do not use spectrometry and rely on visual inspection of CSF for reporting xanthochromia. The number of red cells in each sample can also assist in diagnosis.

Diagnose a subarachnoid haemorrhage if the LP sample shows evidence of xanthochromia on spectrophotometry.[38] Consider alternative diagnoses if the LP sample shows no evidence of xanthochromia on spectrophotometry.[38]

Once the diagnosis of SAH is confirmed, urgently discuss with a specialist neurosurgical centre the need for transfer of care of the patient to the specialist centre.[38] See Referral below.

Practical tip

Possible reasons for a false-positive (CSF looks xanthochromic) result include:[89][91]

High protein content in CSF

Contamination with iodine used for disinfection

Perimesencephalic haemorrhage

Brain or spinal arteriovenous malformations

Cerebral arterial dissection

Vasculitis

Stroke

Venous sinus thrombosis

Sickle cell disease

Pituitary apoplexy

Substance abuse.

Measure CSF opening pressure in all patients with sudden onset of severe headache. Abnormal CSF pressure may indicate an alternative diagnosis.[46]

If elevated: consider cerebral venous sinus thrombosis or idiopathic intracranial hypertension. See Idiopathic intracranial hypertension.

If reduced: consider low pressure headache.

Evidence: Lumbar puncture

A lumbar puncture only adds further diagnostic yield in a very-high-probability patient for SAH.

There is good evidence that a negative CT scan performed within 6 hours from headache onset in a person with a normal neurological examination effectively excludes SAH.[51][77][78][79]

In practice, most patients do not present to hospital within 6 hours of onset of symptoms. Therefore, in these patients, a lumbar puncture (LP) is often carried out if the CT scan is negative or inconclusive. However, LP is an invasive method with reported low specificity, low clinical impact, and low diagnostic yield.[92][93][94][95][96][97] It also requires laboratory services and experienced staff.

The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) advises against routinely offering an LP if a CT head scan done within 6 hours of symptom onset is reported and documented by a radiologist to show no evidence of SAH.[38]

Instead, NICE recommends to consider alternative diagnoses and seek advice from a specialist.

If the CT head scan is done after 6 hours and shows no evidence of a subarachnoid haemorrhage, NICE recommends to consider an LP, as the risk of a false-negative scan increases after 6 hours (sensitivity >95% within 6 hours versus 85.7% to 90% after 6 hours).

If carrying out an LP in these patients, NICE recommends waiting until at least 12 hours after symptom onset; diagnostic accuracy of earlier LP is unreliable due to the time it takes for bilirubin to appear in the CSF.[38][51]

Some guidelines state that SAH cannot be excluded based on a normal CT scan alone.[39][43]

The European Stroke Organization recommends that lumbar puncture must be performed in any patient with clinically suspected SAH despite negative CT findings. It advises to do this 6-12 hours after symptom onset because blood degradation can take some hours.[43]

A disadvantage of not performing an LP is that an alternative diagnosis may be missed; however, an LP is also associated with harms, with around 25% of people developing post-LP headache.[38][51]

How to perform a diagnostic lumbar puncture in adults. Includes a discussion of patient positioning, choice of needle, and measurement of opening and closing pressure.

Patients with negative CT and LP

Exclude SAH if both CT and LP are negative.[104] This strategy is valid for up to 2 weeks from bleed because the sensitivity of LP decreases 2 weeks after the bleed.[89]

Once a diagnosis of SAH is confirmed, urgently discuss with a specialist neurosurgical centre the need for transfer of care of the patient to the specialist centre.[38]

High-volume centres where treatment is provided by a multidisciplinary team including neurosurgeons, neurointensivists, neuroanaesthetists, and interventional neuroradiologists are associated with better outcomes such as lower inpatient mortality and increased discharge home.[45][105]

When referring the patient to a neurosurgical unit, specify the following to inform management:[106]

Time from onset of symptoms

Age

Comorbidities

Level of consciousness

Any neurological deficit.

Do not use a SAH severity score in isolation to determine the need for, or timing of, transfer of care to a specialist neurosurgical centre.[38][52]

Cerebral angiography

Cerebral angiography is the gold standard for detection and localisation of ruptured aneurysms.[43] Computed tomography angiography is the preferred method of angiography as it is quick, convenient, and non-invasive.[38][43]

Computed tomography angiography (CTA)

Request CTA in patients with confirmed SAH to identify the causal pathology, define anatomy, and plan the best option to secure the aneurysm related to the haemorrhage.[38]

Some studies have reported, on a per-aneurysm basis, sensitivities and specificities surpassing 95% and 96%, respectively.[107]

CTA is the preferred angiography method as it is quick, convenient, and non-invasive.[38][43]

If CTA shows an intracranial arterial aneurysm and the pattern of subarachnoid blood is compatible with aneurysm rupture:[38]

Diagnose an aneurysmal SAH

Seek specialist opinion without delay from an interventional neuroradiologist and a neurosurgeon.

If CTA shows an intracranial arterial aneurysm but the pattern of subarachnoid blood is not compatible with aneurysm rupture:[38]

Seek specialist advice without delay from an interventional neuroradiologist and a neurosurgeon.

If CTA of the head does not identify the cause of the SAH and an aneurysm is still suspected, consider digital subtraction angiography (DSA), or magnetic resonance angiography if DSA is contraindicated.[38]

Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA)

If CTA of the head does not identify the cause of the SAH and an aneurysm is still suspected, consider DSA, or MRA if DSA is contraindicated.[38]

MRA and DSA are more complex and time-consuming procedures that need specialist input and have a higher risk of complications compared with CTA.[38]

DSA is the gold standard investigation and is commonly carried out when CTA is negative but there is a high suspicion of aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage, whereas the complexities involved in obtaining high-quality MRA images make this procedure less beneficial.[38][108]

A meta-analysis has shown that MRA has a sensitivity of 95% and a specificity of 89%.[109]

DSA can also be useful compared with non-invasive imaging for identification and evaluation of cerebral aneurysms if surgical or endovascular treatment is being considered.[36]

If DSA or MRA shows an intracranial arterial aneurysm and the pattern of subarachnoid blood is compatible with aneurysm rupture:[38]

Diagnose an aneurysmal SAH

Seek specialist opinion without delay from an interventional neuroradiologist and a neurosurgeon.

If DSA or MRA shows an intracranial arterial aneurysm but the pattern of subarachnoid blood is not compatible with aneurysm rupture:[38]

Seek specialist advice without delay from an interventional neuroradiologist and a neurosurgeon.

Patients with negative angiography

Consider other diagnoses if angiography does not show an intracranial arterial aneurysm.[38]

A specialist might recommend a repeat angiography if suspicion of SAH remains high despite a negative angiogram. European guidelines recommend carrying out a repeat angiography, if indicated, in 4 to 14 days after the initial angiogram.[43] Up to 24% of patients with SAH and an initial negative angiography have an aneurysm found on repeat angiography.[110][111][112][113]

Practical tip

Be aware that some patients with an initial negative angiogram have blood in the cisterns around the midbrain, which reflects a perimesencephalic pattern of haemorrhage. This is called a SAH without aneurysm (perimesencephalic SAH [PMSAH]) and is defined by exclusion of an aneurysmatic bleed and typical location of blood within the perimesencephalic and prepontine cisterns (i.e., no blood in sylvian and interhemispheric fissure).[55][115] Although this topic does not cover PMSAH, it is worth bearing in mind these important considerations for suspected PMSAH:

Request DSA only if CT angiography was not considered to be sufficient to exclude aneurysmal bleeding or if there is diagnostic doubt on the perimesencephalic pattern of the SAH[43]

Do not repeat angiography in cases of a negative baseline DSA after PMSAH, because the risk of the procedure outweighs the chance of finding an aneurysm.[43]

Electroencephalogram (EEG)

Order a standard EEG if you suspect non-convulsive status epilepticus. See Status epilepticus.

Do not perform routine continuous EEG monitoring in patients with SAH.[43][116]

Non-convulsive status epilepticus can be a diagnosis of exclusion. Routine continuous EEG monitoring in SAH is not recommended as it is labour-intensive, can be misinterpreted, and lacks proof of effectiveness.[43][116]

Practical tip

Do not assume clinical deterioration is due to non-convulsive status epilepticus until other causes of deterioration have been excluded.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer