Approach

Physicians and other healthcare professionals play a central role in motivating and assisting people who smoke to stop.[2] Physicians are a credible and trusted source of advice to stop, have opportunities to provide this message to most smokers, and can connect people to services offering behavioural support and pharmacotherapy. Ultimately, smoking cessation interventions may be brief or more comprehensive in nature, depending on location and individual patient circumstances.

Two commonly used smoking cessation models are:[71]

Very brief advice for smoking, based on an 'Ask, Advise, Assist' structure, which encourages clinicians to ask patients about tobacco use, advise them to stop, and assist them by signposting them to specialist smoking cessation services offering pharmacotherapy and behavioural support.

A more comprehensive intervention for smoking cessation, which can be provided using the '5 A's' structure: 1) ask about tobacco use; 2) advise to stop through clear, personalised messages; 3) assess willingness to stop; 4) assist in stopping; and 5) arrange follow-up and support.

See Management approach.

Identifying individuals at high risk of smoking-related harm

Published guidance from a number of countries advises prioritising specific groups who are at high risk of tobacco-related harm for intervention, such as people with mental health problems, those with conditions made worse by smoking, those in hospital or who have recently been hospitalised, those preparing for surgery, and pregnant women.[63][72]

All patients should also be assessed for second-hand smoke exposures, especially individuals who are at significant risk for negative outcomes (e.g., pregnant women, people with known asthma or COPD, people with known cardiac or vascular disease).

Discussing smoking cessation in the context of smoking-related medical disease specific to the individual may be beneficial.

Asking about tobacco and nicotine use

Assess smoking status and usage at every healthcare encounter.[2][71]

Healthcare professionals should ask all patients whether they smoke tobacco, and record their smoking status.[72] It is important to ask the person if they ever smoke cigarettes, in order to identify people who smoke intermittently. All healthcare practices and services should have a system for identifying all people who smoke, as well as for documenting current tobacco use.[72] Smoking status should be readily visible to the physician or healthcare professional at the point of care.[73][74]

For example, for an outpatient clinic, healthcare workers who obtain vital signs may determine the smoking status of each patient through a set of standard questions. The smoking status should then be clearly indicated on the vital sign record sheet so that it is visible to the healthcare provider. This smoking status identification system should be designed by clinic personnel to fit into the clinic's usual routine of obtaining and recording vital signs so as to minimise disruption of the clinic's workflow.[73]

In both primary and secondary care, the new patient visit and routine check-ups may be an opportunity to carry out a more detailed assessment of smoking.[72]

The evidence supporting the effectiveness of a smoking status identification system is substantial, and the use of such a system should be considered the standard of care.[2] The electronic medical record allows for prompts to be embedded within the patient questionnaire. However, responses may be limited by lack of standard terminology and granularity for data collection, shifting cultural attitudes regarding smoking, and potentially frequent changes in an individual's smoking behaviour.[75]

Ask about the type of tobacco product used and duration of use, including water pipe use and other smokeless tobacco products (snuff, ground, or chewing tobacco), as well as e-cigarette use, as use of e-cigarettes also results in nicotine addiction. It is common for people to use both cigarettes and e-cigarettes concurrently. Discuss any stopping attempts and aids to stop smoking that the person has used before, including personally purchased nicotine-containing products.[63]

Assessment of the degree of nicotine dependence predicts the difficulty that a person may have in stopping smoking, and the likely intensity of treatment required. Number of cigarettes per day and time to first cigarette after waking are useful questions to indicate which people may have more problems with nicotine dependence and to guide therapy choices in those who are ready to stop.[76]

Assessing willingness to stop

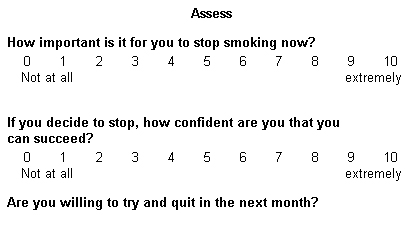

The following may be used to assess readiness to stop smoking. The person is first asked the following:

"How important is it for you to try to stop smoking now?"

"If you decide to stop, how confident are you that you can succeed?"

The person may then be asked to record the answer to the questions on a scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 10 (extremely), and this can be explored by the clinician and patient together: for example, "Why did you select 4 instead of 0?". This process may help the individual to move up the motivational and confidence scale, and provides an assessment of motivation and self-efficacy.

The person may be asked to reflect on prior attempts: "What has worked for you in the past? What hasn’t?"

The person may then be asked: "Are you willing to try to stop in the next month?"

Interventions based on the smoker's 'stage of change' (i.e., pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, or action) have been popular. However, there is little evidence that these stage-based interventions are more effective than more straightforward strategies of determining whether the person is ready to attempt to stop.[2][77]

Note that an assessment of willingness to stop is advised as part of a more comprehensive 5 A's approach to smoking cessation, but does not typically form part of a briefer approach to smoking cessation; an alternative to assessing willingness to stop is to offer a proactive offer of treatment to all smokers.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Questionnaire to assess and improve motivation and self-confidence for stoppingFrom the collection of Dr Theodore W. Marcy [Citation ends].

Additional questions

Comorbidities that may affect treatment choices should also be assessed, including depression, schizophrenia, substance use disorder, current pregnancy or breastfeeding, seizure disorder or lowered seizure threshold, hypertension, unstable cardiac disease or serious arrhythmia, asthma, temporomandibular joint disorders, or dental disorder.[63]

[  ]

]

Investigations

Smoking status is obtained by history and self-report. Commonly used assessment tools for establishing the degree of smoking/nicotine dependence may be useful, and include the Heaviness of Smoking Index (HSI) and the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND).[78][79] PhenX Toolkit: protocol - Heaviness of Smoking Index Opens in new window National Institute on Drug Abuse: instrument - Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) Opens in new window The degree of nicotine dependence predicts the difficulty that an individual will encounter in stopping smoking, and the likely intensity of treatment.

Cotinine and/or carbon monoxide (CO) testing may be useful where additional motivation or proof is required. Cotinine is the primary metabolite of nicotine and is commonly used as a biomarker to detect tobacco exposure, and different levels have been suggested to differentiate between total abstinence, passive tobacco exposure, and active tobacco exposure.[80]

In certain scenarios, it may be important to confirm the smoking status of individuals (e.g., with cotinine testing). It is known that smoking prior to total joint arthroplasty, for example, increases the risk for poor outcomes, including infections, delayed wound healing, and mortality, and there is evidence that when patients know they will be tested, it improves their stopping rates almost twofold, from 15.8% to 28.2%.[81][82] Some centres require proof of abstinence prior to organ transplant or other high-risk surgeries.

CO monitoring involves measurement of exhaled breath to give an indication of levels of CO in the blood, given that CO is a marker of recent smoking. CO monitoring is recommended in some countries (e.g., the UK) as a motivational tool to facilitate smoking cessation.[63] According to UK guidance, CO measurement is recommended at each contact during smoking cessation in order to gauge progress and help motivate people to stop smoking. Guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK states that a CO level of 10 parts per million (ppm) or less suggests that the person is a non-smoker.[63] However, note that clinical experience indicates that any value above 5 ppm usually suggests exposure to tobacco smoking, either from personal use or from second-hand exposure; further questioning may therefore be warranted for results within this range.[83] CO monitoring is recommended routinely for all pregnant women at antenatal appointments in the UK.[63] In pregnancy, a reading of 4 ppm or above is an indication to offer referral for stop-smoking support according to UK guidance.[63]

Providing feedback to smokers about the physical effects of smoking by physiological measurements (e.g., exhaled CO, lung function, genetic risk factors for cancer) may increase motivation to stop, but there is a theoretical risk that this may cause increased anxiety that may impede stopping efforts.[84] In one Cochrane review, while there was no statistically significant evidence that including risk assessments such as genetic markers for cancer, effect on lung age, and other biomedical markers affected smoking cessation, it did not suggest there was harm in this.[84] The authors of the study instead concluded that when applying a sensitivity analysis that removed those studies at high risk of bias, a benefit was detected.[84]

[  ]

]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer