Approach

Diagnosis is based on clinical suspicion, careful history taking and physical examination, and exclusion of other aetiologies, with a definitive diagnosis confirmed by appropriate microbiological testing if available.

Primary stage of LGV

The primary stage is characterised by painless penile or vulvar inflammation and ulceration at the site of inoculation, which spontaneously heals within a few days. This is often not noticed by the patient and they rarely present at this stage.[1]

History:

Age, sex, history of STIs, HIV status, history of unprotected sexual intercourse (either anal or vaginal), risky sexual behaviour, and history of sexual contact with a resident of an endemic area are key components of the history.

Physical examination:

Inflammation and ulceration may be seen on the genitals or anus; however, as the ulcers heal within a few days, patients rarely present at this stage. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Penile ulceration, a primary manifestation of lymphogranuloma venereumCourtesy of Ronald Ballard; reproduced with permission from The Diagnosis and Management of Sexually Transmitted Infections in South Africa, 3rd ed., Johannesburg, South African Institute for Medical Research, 2000 [Citation ends].

Secondary stage of LGV

Secondary stage typically occurs weeks after development of the primary lesion and presents as painful, unilateral, inguinal or femoral lymphadenopathy, possibly with buboes (often referred to as 'inguinal syndrome'). This is the most common presentation.[1] Patients may also present with symptoms of proctocolitis or bacteraemic spread.

History:

Age, sex, history of STIs, HIV status, history of unprotected sexual intercourse (either anal or vaginal), risky sexual behaviour, and history of sexual contact with a resident of an endemic area are key components of the history.

Patients may commonly complain of fever, malaise, arthralgias, or lower abdominal or back pain.

Patients with proctocolitis may complain of anorectal pain, rectal bleeding, mucopurulent discharge, diarrhoea or constipation, abdominal cramping or tenesmus.

Patients with bacteraemic spread may complain of symptoms associated with the organ system affected (e.g., arthralgia, respiratory compromise, or hepatic pain and/or jaundice).

Physical examination:[7][8][24]

Patients with the classic presentation will present with pain and swelling in the groin. Less commonly a 'groove sign of Greenblatt' (the characteristic sausage-shaped swellings of the inguinal lymph node above the inguinal ligament and the femoral lymph node below the inguinal ligament, where the inguinal ligament forms a groove in between the swellings) may be seen. Erythema nodosum is also occasionally associated.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Inguinal and femoral lymphadenopathy, a secondary manifestation of lymphogranuloma venereumCourtesy of Ronald Ballard, reproduced with permission from The Diagnosis and Management of Sexually Transmitted Infections in South Africa, 3rd ed., Johannesburg, South African Institute for Medical Research, 2000 [Citation ends].

When acquired through the rectal mucosa, proctocolitis is another presentation. Digital rectal examination may be difficult due to tenderness, but will often reveal peri-anal ulcerations, rectal bleeding, mucopurulent discharge, and a reduced anorectal aperture.

Disseminated disease occurs as a result of bacteraemic spread producing conditions including arthritis, hepatitis, pericarditis, pneumonia, or meningoencephalitis.

In women, a pelvic examination can be performed to visualise the cervix and to obtain swabs for testing.

Tertiary stage of LGV

Tertiary stage is characterised by chronic and progressive oedema, which results in enlargement, scarring and ultimately destructive ulceration of the genitalia. This is the most common presentation in women due to a lack of symptoms in primary and secondary stages in women.[1]

Sequelae of chronic infection may result in fibrosis, and formation of sinus tracts and strictures of the anogenital tract as abscesses rupture. In women, this may progress to esthiomene (fibrotic genital elephantiasis), or fistulae involving the urethra, vagina, uterus, or rectum. In men, a physical finding known as saxophone penis or penoscrotal elephantiasis has also been described.[2]

Late complications are rare and have been observed more frequently following proctocolitis. While women are more prone to develop late symptoms and complications, men tend to develop symptoms acutely. Furthermore, the cervix may remain infected indefinitely in females; males are not likely to be infectious after the primary lesion has resolved.[22]

History:

Age, sex, history of STIs, HIV status, history of unprotected sexual intercourse (either anal or vaginal), risky sexual behaviour, and history of sexual contact with a resident of an endemic area are key components of the history.

Physical examination:

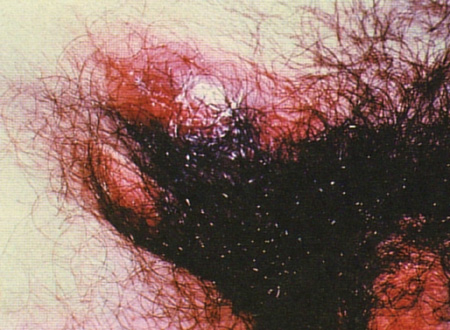

In the tertiary stages of presentation, clinical characteristics are marked by chronic and progressive oedema, which result in enlargement, scarring, and ultimately destructive ulceration of the genitalia. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chronic inflammation from inguinal buboes leading to scarring and fibrosis, a tertiary manifestation of lymphogranuloma venereumCourtesy of Ronald Ballard, reproduced with permission from The Diagnosis and Management of Sexually Transmitted Infections in South Africa, 3rd ed., Johannesburg, South African Institute for Medical Research, 2000 [Citation ends].

Less common findings include anogenital strictures, fistulae or sinus tracts; genital elephantiasis; saxophone penis or esthiomene. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Lymphoedema of the genitals with abscess and fistula formationCourtesy of Ronald Ballard, reproduced with permission from The Diagnosis and Management of Sexually Transmitted Infections in South Africa, 3rd ed., Johannesburg, South African Institute for Medical Research, 2000 [Citation ends].

Laboratory evaluation

Diagnosis must be confirmed by appropriate microbiological testing, regardless of the stage of disease. Identification of LGV serotypes of Chlamydia trachomatis is the definitive diagnosis. C trachomatis can be distinguished from other species of Chlamydiae by 16S ribosomal ribonucleic acid sequence analysis.[25] On the basis of antigenic specificity confirmed by monoclonal antibodies and molecular sequencing of the major outer-membrane protein, 18 sub-species of C trachomatis have been identified, designated by the letters A through to L.[26] LGV is caused by genovars/serovars L1, L2, and L3. L2 is the most common of the genovars/serovars that cause LGV.

Swabs are taken from genital ulcers, the cervix, and if symptoms of proctocolitis are present, the rectum. If a patient presents with classic symptoms (inguinal lymphadenopathy) or is otherwise asymptomatic, then urethral swabs or urine specimens are collected.

Molecular techniques have a greater sensitivity compared with culturing and so are preferred first; culturing is not necessary if molecular techniques are available. Nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) for C trachomatisdetects all genovars, including LGV genovar-specific C trachomatis,but cannot distinguish between them In the US, although NAAT is not cleared by the US Food and Drug Administration for analysis of rectal or oropharyngeal specimens, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends testing by NAAT for patients presenting with proctitis or extragenital infections.[27]

A definitive diagnosis can only be made with LGV-specific testing, such as PCR-based genotyping. Specimens that are NAAT-positive may be sent for confirmation of a LGV-specific genovar by real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR); however, results may take several weeks to return. A presumptive diagnosis of LGV can be made with a positive NAAT from a patient with proctocolitis or clinical suspicion while awaiting LGV-specific testing.

Radiological imaging may have a role in the evaluation of deep pelvic anatomy during the later stages of presentation.

Those with signs and symptoms of proctocolitis may be referred for anoscopy or proctosigmoidoscopy. A high white blood cell count on Gram stain from anoscopy/proctosigmoidoscopy in high-risk patients with proctocolitis may support a diagnosis of LGV.[21] Colonoscopy may be considered if inflammatory bowel disease is suspected. LGV is generally confined to the distal sigmoid colon and rectum, whereas Crohn's disease may present anywhere in the gastrointestinal tract.[24] Histologically, however, no pathognomonic features of LGV have been described, and findings with LGV may overlap with findings of inflammatory bowel disease, such as crypt abscess and focal granuloma formation.[28]

Serological testing with either complement fixation or microimmunofluorescence may be useful if direct detection has not been successful or if molecular testing is not available. Isolation of C trachomatis from culture of fluid aspirate or swabs of genital or rectal ulcers is the most specific study; however, techniques vary with laboratory and are not widely available as they are more labour intensive and less sensitive than other molecular techniques.

Genovar typing is an emerging test that may be used with reference testing for epidemiological purposes.

The Frei test, derived from chlamydial antigens, is now obsolete. A positive test does not differentiate past from present chlamydial infection or infection with other chlamydial species.

STI testing

Patients who are being tested for LGV should also be tested for other STIs (e.g., syphilis, HIV, gonorrhoea, herpes, and hepatitis). Patients whose HIV tests are negative may be offered HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).[29][30]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer