Approach

Any form of suspected systemic vasculitis should be investigated urgently, because if left untreated these diseases cause high morbidity and mortality. Diagnosis of polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) can be challenging because individual features are not distinguishable from those of many other diseases. The combination of constitutional symptoms and ischaemic symptoms in one or more organ systems should raise the possibility of a systemic vasculitis.

Non-specific systemic symptoms such as fever, weight loss, weakness, and myalgia are found in 65% to 80% of patients at the time of diagnosis.[16][20] Organ-specific manifestations may be present at disease onset, involving just one organ or several systems, or the disease may follow a more indolent course, with organ involvement being recognised only months or years later.

Renal involvement in the systemic vasculitides carries a poor prognosis. Glomerulonephritis is not a feature of PAN, but it is common in anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) vasculitis. Making this distinction early by way of urinalysis for protein, blood, and casts is a simple first-line test that can guide further investigation and treatment.

Possible organ-specific manifestations

The following body systems may be involved at disease onset in non-HBV-related PAN:[16][20]

Nervous system (in 55% of patients)

Skin (in 44%)

Abdominal organs (in 33%)

Kidneys (in 11%)

Musculoskeletal system (in 24% to 80%).

Similar rates are found for organ involvement in hepatitis B virus (HBV)-related PAN.[20]

Nervous system involvement typically presents as mononeuritis multiplex, with sensory symptoms preceding motor deficits.[31] Central nervous system involvement is a less frequent finding and can present as encephalopathy, seizures, or stroke.[25][32]

Skin manifestations include purpura, nodules, livedo reticularis, ulcers, bullous or vesicular eruptions, and segmental skin oedema.[20][22][33][34]

In abdominal involvement, pain is an early feature of mesenteric artery disease. Progressive involvement may cause bowel, liver, or spleen infarction; bowel perforation; or bleeding from a ruptured arterial aneurysm.[35] Less common presentations include appendicitis, pancreatitis, or cholecystitis resulting from ischaemia or infarction of these organs.[36]

Vasculitis of the renal arteries is a common finding. It can present with renal impairment or renal infarcts or with rupture of renal arterial aneurysms. Glomerular ischaemia may result in mild proteinuria or haematuria, but red cell casts are absent because glomerular inflammation is not a feature. If there is evidence of glomerular inflammation such as urinary casts, then an alternative diagnosis such as microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) or granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA, formerly known as Wegener's granulomatosis), must be considered. Hypertension is a manifestation of renal ischaemia via activation of the renin-angiotensin system.[37]

Musculoskeletal involvement may manifest itself by arthritis, arthralgia, myalgia, or muscle weakness. When muscle is involved, it provides a useful site for biopsy.[20][24]

Other manifestations may involve almost any organ system. Cardiac ischaemia, cardiomyopathy, breast or uterine involvement, and ocular symptoms from either ischaemic optic neuropathy or retinopathy have been described.[20][25][38] Although testicular pain from ischaemic orchitis is a characteristic feature, it is an uncommon presentation.[20][39]

Physical examination

In patients in whom vasculitis is suspected, a thorough physical examination is necessary to identify the organ systems potentially involved. At a minimum, the examination should include:

General - look for elevated temperature and weight loss (current and previous)

Skin - look for purpura, ulcers, bullous or vesicular eruptions, areas of skin infarction, and livedo reticularis

Ocular - test for visual impairment and look for retinal haemorrhage and optic ischaemia

Neurological - test for peripheral neuropathies, stroke, and confusion

Abdominal - assess for abdominal tenderness or peritonitis, and perform a rectal examination for signs of blood loss

Cardiovascular - check peripheral pulses and blood pressure, and look for signs of congestive cardiac failure, pericarditis, or valvular pathology

Musculoskeletal - assess for synovitis, arthralgia, and muscle tenderness or weakness

Genitourinary - assess for testicular tenderness

Ear, nose and throat - look for nasal crusting and signs of sinusitis, and assess for hearing loss; the presence of these features would suggest an alternative diagnosis such as GPA rather than PAN

Respiratory - lung involvement is not seen in PAN, and abnormal respiratory findings should suggest an alternative diagnosis

Blood pressure - a diastolic blood pressure of >90 mmHg can be suggestive of PAN.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A purpuric rash is a common featureFrom the collection of Dr Loic Guillevin [Citation ends].

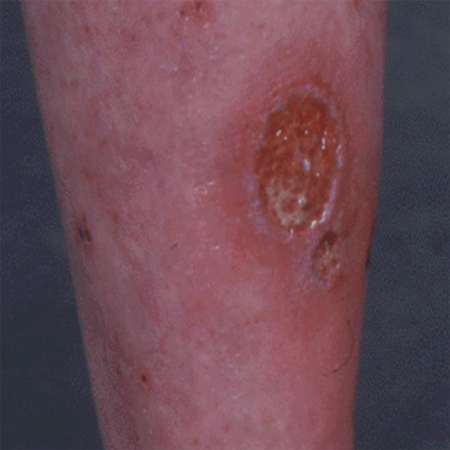

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Skin ulcers in the lower limbs are a common manifestation of PANFrom the collection of Dr Raashid Luqmani [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Skin ulcers in the lower limbs are a common manifestation of PANFrom the collection of Dr Raashid Luqmani [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Large skin ulcer from a patient with PANFrom the collection of Dr Raashid Luqmani [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Large skin ulcer from a patient with PANFrom the collection of Dr Raashid Luqmani [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Vesiculo-bullous skin rash with necrosisFrom the collection of Dr Raashid Luqmani [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Vesiculo-bullous skin rash with necrosisFrom the collection of Dr Raashid Luqmani [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Digital gangrene from medium vessel vasculitisFrom the collection of Dr Raashid Luqmani [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Digital gangrene from medium vessel vasculitisFrom the collection of Dr Raashid Luqmani [Citation ends].

Laboratory testing

There are no specific laboratory tests to diagnose PAN, but some tests can be useful to support the diagnosis, identify organs that may be affected, and rule out alternative diagnoses.

Test results that help to support the diagnosis include:

Raised CRP and/or erythrocyte sedimentation rate, which suggests systemic inflammation

Raised fibrinogen, a marker of acute inflammation; fibrinogen levels may be low in catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome

Raised serum creatinine, typically without haematuria or proteinuria on urinalysis, which may indicate renal ischaemia or infarction; however, significant proteinuria or haematuria (especially red cell casts) would suggest glomerular disease, which is not a feature of PAN

Abnormal liver function tests, which may suggest hepatitis, either from HBV or as a result of ischaemic hepatitis caused by PAN involving the hepatic arteries[20]

Positive HBV serology, which is supportive of the diagnosis[20]

FBC, which may show anaemia as a result of chronic inflammation or from gastrointestinal blood loss

Low complement levels, caused by activation of the complement cascade by immune complexes (especially in HBV-related PAN)

Creatine kinase, which is either normal or mildly elevated, regardless of any muscle involvement.

Tests that should be done to exclude other causes include:

Blood cultures, to exclude endocarditis or other infective mimics of vasculitis

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) serology and cryoglobulins; although HCV has been associated with a skin-limited manifestation of PAN, it is typically associated with a small-vessel vasculitis related to cryoglobulinaemia

ANCA, which if positive would suggest another type of vasculitis, such as GPA or MPA; a negative ANCA is useful in supporting the diagnosis of PAN in the right context[3][20]

Rheumatoid factor and antibodies to cyclic citrullinated peptides (anti-CCP antibodies), to rule out rheumatoid arthritis, especially in a patient presenting predominantly with arthritic features

Antinuclear antibodies and anti-double-stranded DNA antibodies in patients with clinical features consistent with systemic lupus erythmatosis or other connective tissue diseases

Lupus anticoagulant, antiphospholipid antibodies and B2 glycoprotein, which may be present in antiphospholipid syndrome

HIV testing

Genetic testing for lack of function mutations in the adenosine deaminase 2 (ADA2) gene (previously called the CECR1 gene) in young patients with features of PAN, especially if stroke is part of the presentation.

Imaging

Conventional angiography, MR or CT angiography, Doppler ultrasound, and chest x-ray all have their place in the diagnosis.

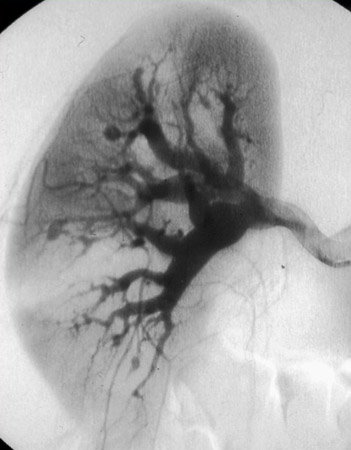

Conventional angiography is the imaging modality of choice, and should be performed if there is a clinical suspicion of PAN. The reported sensitivity is as high as 89%. The specificity is 90% when performed in patients suspected of having vasculitis.[40] Classical findings are multiple small aneurysms, vessel ectasia, and focal occlusive lesions in medium-sized vessels, most typically in the renal and mesenteric arteries.

MR or CT angiography are less invasive alternatives to conventional angiography, but they are much less sensitive in showing microaneurysms.[41] They do have the advantage of being able to show areas of renal infarction and other potential pathology. In the setting of a high suspicion of PAN and a normal CT or magnetic resonance angiography, it is still necessary to proceed to conventional angiography.

Doppler ultrasound has been noted in individual case reports as successfully identifying renal and hepatic aneurysms related to PAN.[42]

PAN does not affect the lungs, but chest x-ray may be useful in ruling out other diseases, such as other vasculitides, which may affect the lungs and in excluding infection. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Renal angiogram showing aneurysms, a classical feature of PANFrom the collection of Dr Raashid Luqmani [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Renal angiogram showing aneurysms and microaneurysmsFrom the collection of Dr Loic Guillevin [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Renal angiogram showing aneurysms and microaneurysmsFrom the collection of Dr Loic Guillevin [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Mesenteric angiogram showing small and micro aneurysmsFrom the collection of Dr Loic Guillevin [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Mesenteric angiogram showing small and micro aneurysmsFrom the collection of Dr Loic Guillevin [Citation ends].

Biopsy

Biopsy should be performed if angiography is not available or does not conclusively show a medium-vessel vasculitis. A number of organs or tissues can be sampled. The tissue chosen for sampling should be directed by evidence of clinical involvement from the history or physical examination. Muscle, peripheral nerves, kidney, testis, and rectum, when involved, provide the best targets. A positive skin biopsy does not always indicate systemic involvement.[43]

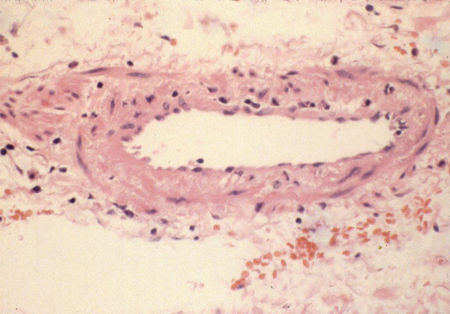

A biopsy showing a medium-sized artery with evidence of focal and segmental transmural necrotising inflammation is supportive of a diagnosis of PAN.[25][43]The presence of clinical or laboratory features indicating involvement of small vessels should be pursued[44]because it suggests an alternative form of vasculitis such as MPA.

In pathological descriptions of PAN, the involvement of vessel bifurcations is reported to be a common feature. Different stages of inflammation and scarring, as well as areas of normal vessel wall, often co-exist. Areas of acute inflammation typically have a pleomorphic cellular infiltrate of lymphocytes, neutrophils, macrophages, and eosinophils. Aneurysms can occur at the site of active lesions. Proliferative scarring in other areas may lead to vessel narrowing.[25][37][43][44][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Pathology specimen of a medium-sized muscular artery showing transmural inflammationFrom the collection of Dr Raashid Luqmani [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Biopsy specimen showing florid transmural inflammation of a small arteryFrom the collection of Dr Loic Guillevin [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Biopsy specimen showing florid transmural inflammation of a small arteryFrom the collection of Dr Loic Guillevin [Citation ends].

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer