Details

This topic on the recognition and management of frailty in older people is a practical guide aimed at all members of the healthcare team including doctors, pharmacists, advanced nurse practitioners, physician associates, and paramedics.

Frailty is an issue that affects all specialties within medicine and surgery. Health professionals from multiple disciplines need to be involved to ensure it is managed well.[1] By having an awareness and understanding of frailty, healthcare professionals can provide person-centred care to individuals with frailty, and support to their families with the goal to improve outcomes.

What is frailty?

Frailty is a distinctive health state, that is related to the ageing process, in which multiple body systems gradually lose their in-built reserves.[2] It is characterised by a decline in functional state across multiple physiological systems.[3] This decline means more vulnerability to stressor events. Even a 'minor' change such as a new medication, or something more major like an infection or surgery, can result in a disproportionate change in state of health, taking a person from being independent to dependent.[3]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Vulnerability of frail older people to a sudden change in health status following a minor illness. The green line represents a fit older person who, following a minor stress such as an infection, experiences a relatively small deterioration in function and then returns to homeostasis. The red line represents a frail older person who, following a similar stress, experiences a larger deterioration which may manifest as functional dependency and who does not return to baseline homeostasisClegg A et al. Lancet 2013 Mar 2;381(9868):752-62; used with permission [Citation ends].

Living with frailty increases the risk of multiple adverse outcomes including falls, admission to hospital, and death.[4]

Frailty is not an inevitable consequence of ageing. Many people can reach an advanced age without developing frailty.[3] Terms like multimorbidity, disability and frailty are sometimes used interchangeably but are distinct, albeit related, terms. Data from one large cohort study in community dwelling adults over the age of 65 looked at the overlap between disability, multimorbidity and frailty.[5] It looked at a total of 5317 subjects aged 65-101 who had comorbidity and/or disability and/or frailty. It found that there is overlap, but not concordance, in the co-occurrence of frailty, comorbidity, and disability. The study concluded that comorbidity is an aetiological risk factor for frailty and that disability is an outcome of frailty.[5] This pattern of data has been subsequently echoed in studies across Europe.[6][7] The following image represents the findings of one of these studies in 4414 participants from the population-based Age Gene/Environment Susceptibility Reykjavik study.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Venn diagram displaying the overlap in prevalence (%) between frailty, multimorbidity and disabilityAdapted from Aarts S et al. J Frailty Aging 2015;4(3):131-8; used with permission [Citation ends].

This supports the hypothesis that frailty may cause disability, independent of clinical diseases. Indeed, frailty can be thought of as a state of pre-disability. This is important as frailty is therefore an independent predictor of adverse outcomes.[5]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Stages of living with frailtyCreated by BMJ Knowledge Centre [Citation ends].

Frailty is a result of changes to multiple physiological systems, particularly neuromuscular, neuroendocrine and immunological changes.[8] These changes are cumulative, and result in a decline in an individual's physiological reserve or intrinsic capacity. When a cumulative threshold is reached, the ability of an individual to resist even minor stresses is compromised.[8]

There is a complex interplay between physiological systems including:

Muscle mass

Energy levels

Nutrition

Disease

Mobility

The way these processes interact has been described as the frailty cycle or spiral where any increase in frailty increases the risk of further decline to disability and even greater frailty.[8]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: The frailty cycle; VO2 = volume of oxygen utilisationAdapted from Fried L et al. Frailty and failure to thrive. Principles of geriatric medicine and gerontology 2003 5th edn. New York: McGraw-Hill; used with permission [Citation ends].

Age, although not synonymous with frailty, is the biggest independent risk factor for developing frailty.[9] A large cohort study in people aged over 75 years, or aged 65-75 years with at least one morbidity, found that the following were also factors associated with higher risk of developing frailty:[9]

Cognitive impairment

Depressive symptoms

Diabetes

Various other risk factors for developing frailty have also been identified, such as:[10][11][12]

Physical inactivity

High cardiovascular disease risk score

High inflammatory-related disease count

Frailty is also related to nutrition (both an excess and a deficit), although research suggests a stronger relationship with malnutrition due to undernutrition rather than being overweight or obese.[13] Similarly, alcohol use has a complex relationship with frailty.[14] High alcohol consumption in midlife is associated with frailty in later life.[14] Moderate alcohol consumption in midlife has been associated with lower risk of developing frailty, specifically moderate alcohol consumption taken with meals in a Mediterranean drinking pattern is associated with a lower risk of developing frailty.[15] Zero consumption in old age is also associated with frailty, although this is possibly due to confounding, with consumption patterns being affected by ill health and indeed health problems related to previous alcohol use, thereby a reverse causality.[14]

As well as physical and lifestyle risk factors, there may also be more complex mechanisms at play. A 26-year follow-up study of initially healthy men found that self-reported poor health in clinically healthy midlife was associated with frailty status in older age (independently of baseline cardiovascular risk and later comorbidity), raising the possibility of complex psychosocial mechanisms being involved.[16]

The term 'frailty' can mean different things to different people; indeed older people living with frailty don’t necessarily identify as being 'frail'.[17] So why label it at all? To answer this, we need to consider its prevalence and impact at an individual, societal and population level, together with the potential for prevention and for improving outcomes once recognised.

Epidemiology

Reported prevalence of frailty varies widely, from 4% to 59% in people aged over 65. This wide variation is probably due to the use of different methods for operationalising frailty in research.[18] One validation study of the electronic frailty index, which uses the cumulative deficit frailty model (see Models of frailty), in UK primary care patients aged 65-95 years described the following prevalence estimates:[19]

3% with severe frailty

12% with moderate frailty

35% with mild frailty

Although frailty is not defined by age, older adults are at greater risk of becoming frail and the ageing population will lead to increasing prevalence. In 2020, the global population aged 60 years and over was just over 1 billion people, which represents 13.5% of the 7.8 billion world population. This is predicted to reach nearly 2.1 billion by 2050.[20] In the UK, the proportion of people aged ≥85 years is predicted to almost double from the year 2020 (1.7 million people) to 2045 (3.1 million people). ONS: national population projections: 2020-based interim Opens in new window

Frailty affects all aspects of life. From an individual perspective, it is associated with lower mental and physical quality of life scores, and increased risk of adverse health outcomes such as falls, hospitalisation and death.[21][22][23][24][25]

One Danish retrospective study of over 900 inpatients aged >75 years assessed the need for further physiotherapy following discharge and found higher mortality (age- and gender-adjusted) at 1 year in those with frailty versus those without. Hospital admissions were also significantly higher.[25]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Kaplan-Meier plot showing differences in mortality. The figure shows mortality (age and gender adjusted) in frail and non-frail individuals. Mean time at risk was 262.3 days, median 238 daysHoffmann S et al. BMJ Open 2020 Oct 28;10(10):e038768; used with permission [Citation ends].

People with frailty account for the most bed-days used in hospital. One retrospective observational study in a large university hospital in the UK found that frailty (assessed using Clinical Frailty Scale [CFS]) is an independent predictor of mortality, and approximately 20% of patients in the over 75 age group accounted for 80% of events (including deaths) and bed-day use.[26][27] The study found that CFS scores of 7-8 were independent predictors of survival time compared to CFS scores 1-4.[27] In addition, people with frailty are more likely to come to harm from prolonged hospital stays and deconditioning while in hospital.[28][29]

From a public health perspective, studies show a clear pattern of increased healthcare use and cost associated with frailty. This has implications for healthcare resourcing on a local, national and global scale.[4]

Frailty can be considered as a state of pre-disability. There is a cascade of functional decline in older adults from a state of independence to pre-frailty to frailty and then disability in the absence of any intervention. It is important to be aware that this is a dynamic, sometimes even reversible, transition.[30] Targeted intervention may slow or indeed reverse this cascade, especially in its early stages.[31][32] Early identification of frailty in hospital improves healthcare planning and patient outcomes.[24]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cascade of functional decline from independence through frailty to disabilityDent, E et al. J Nutr Health Aging 23, 771–87 (2019) [based on concepts and findings from other studies]; used with permission [Citation ends].

Data from a national report on geriatric medicine by the UK organisation 'Getting it Right First Time' found up to 10% of emergency department attendances and 30% of acute medical unit stays were in people living with frailty.[33][34] Evidence suggests that changing our approach to managing frailty can improve outcomes, for example:

One systematic review looking at the impact of acute geriatric units compared with conventional care for adults over 65 years admitted to hospital showed that not only do they produce a functional benefit but also increase the likelihood of living at home upon hospital discharge.[35]

A subsequent Cochrane Review of 29 trials found that older patients who had comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) on admission were more likely to be alive and living in their own homes at follow-up.[36] See Assessing frailty for more information on the CGA.

Although many hospital trusts in the UK have set up dedicated frailty units, the Society for Acute Medicine's benchmarking audit 2019 identified significant room for improvement. The audit looked at the use of frailty screening and the presence of acute frailty units across UK hospitals and found that the provision of acute frailty services was variable.[37]

The Acute Frailty Network (AFN) is a national quality improvement collaborative in the UK, which was set up with the aim to support acute hospitals to adopt a set of principles to improve the urgent care pathway for people living with frailty. It worked across a number of hospital trusts in the UK to help integrate the CGA for people living with frailty attending urgent care settings. NHS Acute Frailty Network Opens in new window Despite good evidence for the effectiveness of CGA, a staggered difference-in-difference panel event study failed to demonstrate a significant effect of AFN membership on the main outcome measures. The study authors recommend that future research should focus on implementation strategies.[38]

The British Geriatrics Society has provided resources on how to set up a frailty service along with other recommendations across different settings.[39] BGS: frailty hub: setting up and developing frailty services Opens in new window

There is also increasing evidence for the benefit of multidisciplinary assessment and tailored interventions.[36] BGS: comprehensive geriatric assessment toolkit for primary care practitioners Opens in new window Suggested interventions include:

Exercise

Adequate nutrition

Structured medication reviews in people living with frailty in the community

See Living with frailty/ageing well for more details.

Resources

There are two internationally recognised models to characterise frailty:[40]

The phenotype model

The cumulative deficit model

Phenotype mode

The phenotype model identifies frailty on five variables:[5]

Unintentional weight loss

Self-reported exhaustion

Low energy expenditure

Slow gait

Weak grip

Presence of 3 out of 5 is considered ‘frail’, 1 or 2 is ‘pre-frail’, and none is ‘robust’. This model has been validated in several studies.The time needed to test each variable may be a barrier to implementation outside of a research setting and it may overestimate frailty in people with acute illness.[40]

Cumulative deficit model

The cumulative deficit model is based on the concept that frailty is the accumulation over a lifetime of ‘deficit’ variables.[41] These can be signs or symptoms, diseases, disabilities or abnormal laboratory results. Frailty is the accumulation of these deficits; the more the person has wrong with them, the more likely they are to be living with frailty.This model allows for identification of different degrees of frailty.

These models have been developed primarily for use in research. As the concept of frailty has gained momentum, screening tools to quickly identify and assess the risk of frailty are increasingly being used in both primary and secondary care. However, there is no international agreement on a standard instrument.[4] More details are provided below on screening and diagnostic tools that can be used to assess frailty in different acute and community clinical settings.

Key points

Use a recognised tool, such as Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS), to identify frailty early.

If frailty is identified, conduct or refer for a comprehensive geriatric assessment.

Ensure communication aids are available (hearing aids, visual aids).

Obtain a collateral history.

Conduct a pain assessment using a recognised pain scale.

Frailty in the acute setting has its own specific challenges. Clinical presentations are often more acute and more severe, with large numbers of patients and significant time pressures. For this reason, management and considerations around frailty in acute settings are addressed separately to community settings.

Identifying frailty

People with frailty have worse health outcomes, so early identification of patients with frailty allows for a more holistic approach, which can improve outcomes.[42]

Tools to identify frailty in the community, such as the gait speed test, may not be appropriate in the acute clinical context (e.g., for patients with delirium or hip fracture). Use a tool that has been validated in a hospital setting (e.g., the CFS).

Clinical Frailty Scale

The UK Royal College of Physicians (RCP) recommends that a system should be in place to ensure use of an appropriate screening tool, such as the CFS, to identify older people with frailty within 30 minutes of arrival in the emergency department (ED).[1] Dalhousie University: clinical frailty scale Opens in new window The CFS is useful not just to identify frailty but for prognostication and to help guide appropriate management. One retrospective cohort study found that frailty assessment at triage in the emergency department led to appropriate identification of those at risk of higher mortality rates.[24] Readmissions over 2 years increased with an increasing CFS score up to a score of 6, and then plateaued.[24] Higher CFS scores have been associated with reduced survival rates in intensive care units.[43] There is also evidence that CFS has utility in haematology/oncology inpatient settings to guide decisions as to prognosis, potential utility of anticancer therapy or escalation of care.[44] Recognising the implications of frailty can help healthcare professionals discuss the risks and benefits of potential treatments with people living with frailty and their families.

Assess a person’s capability two weeks prior and not how they appear on presentation. Dalhousie University: clinical frailty scale Opens in new window

Be aware that the CFS is not validated for use in people younger than 65 years or in people with a learning disability. It is not suitable for use in people with stable long-term disabilities such as cerebral palsy. Dalhousie University: clinical frailty scale Opens in new window

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Clinical Frailty ScaleAdapted from Dalhousie University. Clinical Frailty Scale version 2.0. 2020; used with permission [Citation ends].

In the UK, the Clinical Frailty Scale App is a free downloadable tool published on behalf of NHS Elect, which presents the CFS as a series of nine questions with a ‘yes/no’ answer. The response to the questions identifies the level of frailty and provides a recommendation about how to approach the patient's care. It can be used in the community and in the acute setting, but in the acute setting it should be based on the patient's capabilities two weeks prior to the hospital attendance/admission.[45]

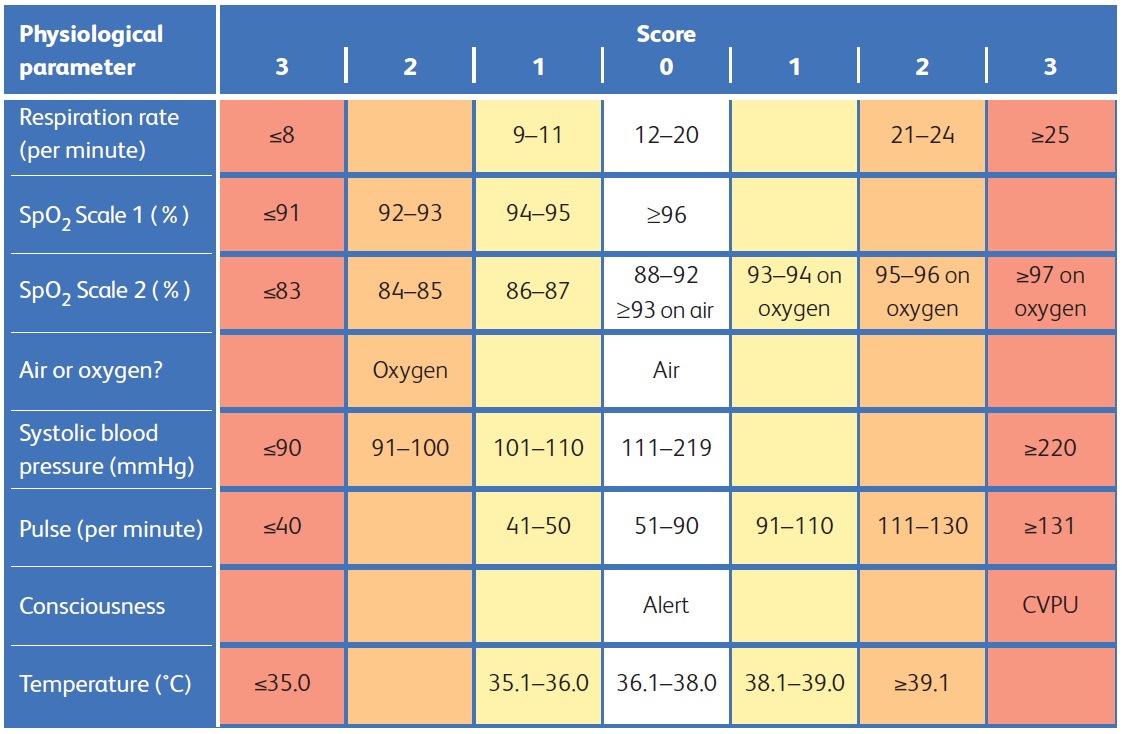

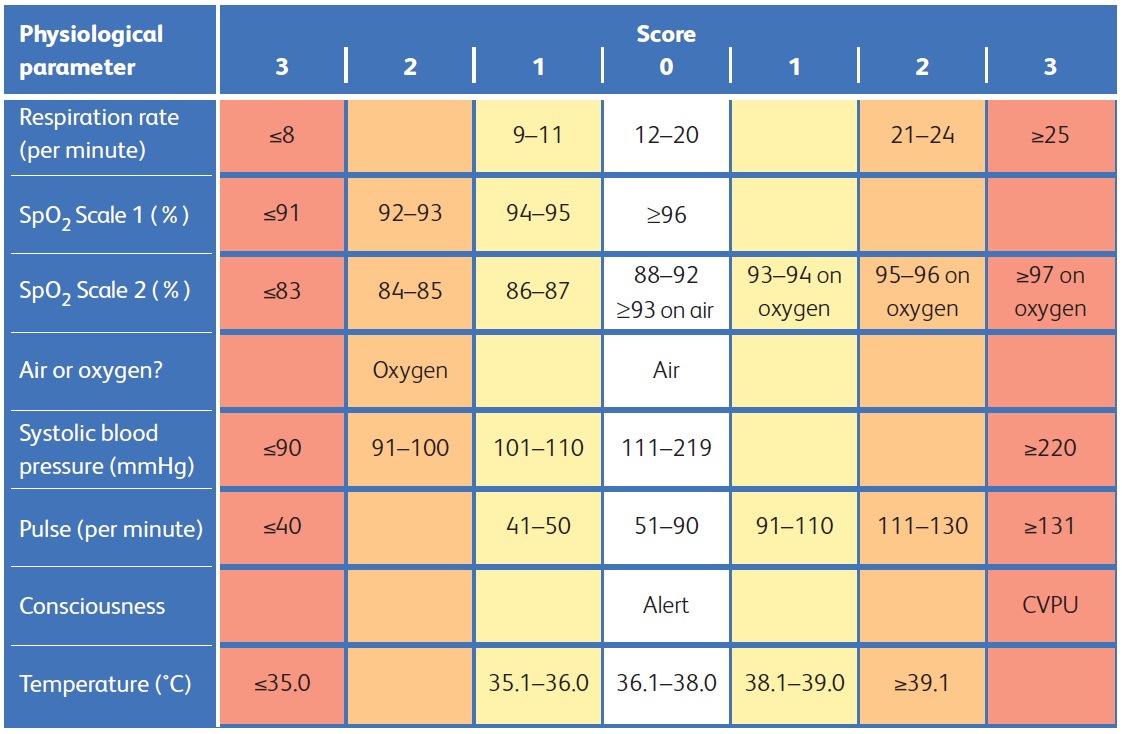

The UK organisation 'Getting it Right First Time' advocates a triple assessment on initial presentation to hospital including CFS, delirium and dementia screen (e.g., 4AT), and a National Early Warning Score (NEWS2).[33] The NEWS2 score was developed by the RCP and has been widely adopted across the NHS in the UK. It uses a simple scoring of physiological parameters to aid early warning signs of patient deterioration and has been evaluated and validated in acute care settings.[46][47] Parameters measured include:

Respiration rate

Oxygen saturation

Systolic blood pressure

Pulse rate

Level of consciousness or new confusion

Temperature

A score of 0-3 is allocated to each parameter, with the magnitude of the score reflecting how extreme the parameter varies from normal. There are two different scales for oxygen saturation levels based on a patient’s physiological target (with scale 2 being used for patients at risk of hypercapnic respiratory failure). The score is then added together and uplifted by 2 extra points if the person is requiring supplemental oxygen to maintain their oxygen saturation. The higher the NEWS2 score the more high risk the patient and a NEWS2 score of 5 or more being the threshold for an urgent response by a clinical team trained in assessment of acutely ill patients.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: National Early Warning Score 2 (NEWS2) is an early warning score produced by the Royal College of Physicians in the UK. It is based on the assessment of six individual parameters, which are assigned a score of between 0 and 3: respiratory rate, oxygen saturations, temperature, blood pressure, heart rate, and level of consciousness. There are different scales for oxygen saturation levels based on a patient’s physiological target (with scale 2 being used for patients at risk of hypercapnic respiratory failure). The score is then aggregated to give a final total score; the higher the score, the higher the risk of clinical deteriorationReproduced from: Royal College of Physicians. National Early Warning Score (NEWS) 2: Standardising the assessment of acute-illness severity in the NHS. Updated report of a working party. London: RCP, 2017. [Citation ends].

In the UK, the patient’s electronic frailty index (eFI) score (used widely in UK general practices) may be available in the ED to check as an additional measure providing a risk score at the point of presentation to hospital to help identify those at risk of frailty. NHS England: electronic frailty index Opens in new window See Community setting: identifying frailty for more information on the eFI.

Medical history

Taking a good history is the cornerstone of diagnosis but especially important for people with frailty as they may have significant multimorbidity and polypharmacy which can be pertinent to aid diagnosis and management. This short video outlines the importance of finding out about:

Past medical history

Current medications

The social situation, for example if any package of care is in place

Video showing an example of taking a medical history.

Patients presenting to the ED may have a ‘do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation’ (DNACPR), or advance care plan (such as Recommended Summary Plan for Emergency Care and Treatment [ReSPECT] or Deciding Right) in the community and it is important to establish if a patient has one to help plan care and make sure any advance decisions are honoured. Resuscitation Council UK: ReSPECT for healthcare professionals Opens in new window Northern Cancer Alliance: advance care plan discussions Opens in new window Even in the absence of any type of advance care plan, or similar, it is important to take a shared decision approach about care and indeed the decision to admit to hospital or not.[40]

Collateral history

In many cases, a person with frailty presenting to the ED might be unable to provide a detailed history. In these situations it is best practice to get a collateral history. This is important not only to aid diagnosis but to involve family and carers in shared decision making and help direct ongoing management.[48] The RCP recommends a call to a relative or carer if the patient arrives at hospital alone. RCP: acute care toolkit 3: acute care for older people living with frailty Opens in new window

Pain assessment

Another barrier to communication can be if a person is in pain. Pain can be difficult to assess, especially in people with dementia or delirium. The RCP recommends an appropriate pain scale should be used.[1][40]

For patients who are cognitively intact, use the numeric rating scale from 1-10 or the Faces Pain Scale:[49][50]

Numeric rating scale from 1-10

The Faces Pain Scale IASP: faces pain scale - revised Opens in new window

For patients with cognitive impairment, validated tools include:[51][52][53][54]

Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia Scale (PAINAD)

Pain Assessment Checklist for Seniors with Limited Ability to Communicate (PACSLAC-II) GeriatricPain.org: pain assessment checklist for seniors with limited ability to communicate-II (PACSLAC-II). Opens in new window

Abbey Pain Scale Australian Pain Society: pain in residential aged care facilities - management strategies Opens in new window

Both an initial pain assessment, and also frequent reassessment of pain control, are crucial to optimal pain management.[40]

Often the decision on the most appropriate setting to continue care hinges on whether the patient with frailty is ‘safe’ to go home.

Some older people may prefer to live with risk rather than have their independence threatened. Clear communication with a person about their wishes and their understanding of risk is key. Often it is assumed that hospital is the perceived ‘safer’ option, but admission to hospital itself is not without risk.[40] Based on local availability of community resources, the decision may be made not to admit if there are safe alternatives.[55] Increasingly in some areas in the UK, initiatives like virtual ward rounds or hospital at home are available to offer added specialist input for patients living with frailty via community-based acute health and care delivery.[56] One Cochrane review found that hospital at home may improve patient satisfaction, probably achieves similar health outcomes and probably reduces the likelihood of relocating to residential care.[57]

If the decision is made to admit, consider where would be the best place to assess the individual. People with frailty have medical complexity and evidence suggests a Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) improves outcomes.[36] Therefore, people living with frailty presenting in an acute hospital setting should be managed in a hospital area where resources (nurses, therapists and social workers) are adequate to conduct a CGA, and managed accordingly.[40]

Resources

People with frailty can present to the emergency department with a wide range of conditions; here we address some of the most common frailty syndromes generally encountered. It should be noted that frailty syndromes often present together, for example consider delirium in a patient presenting with falls, so always consider checking for other syndromes in a patient presenting with apparently a single issue (e.g., a fall). Further information on specific topics often associated with frailty can be found in:

Key points

Diagnose and treat any sustained trauma.

Establish and manage the cause of predisposing factors to fall.

Conduct a structured medication review.

Prevent complications of fall.

Prevent future falls.

Arrange for multi-disciplinary team assessment prior to hospital discharge.

Impact of falls

Falls account for a large proportion of presentations to the emergency department and fall-related injuries are a leading cause of morbidity and mortality.[40] Older people are more likely to fall and also more likely to sustain more significant injury from a fall.[58] Frailty is a risk factor for falls and may be more predictive of worse outcomes than age.[59][60] Data from the UK Trauma Audit and Research Network indicate that major trauma patients are increasingly older people with frailty, suffering trauma from falls.[61] Be aware that even low level falls can cause significant injury.[60] In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends whole body-CT imaging in cases of major trauma but local guidelines and practice across different hospitals vary in use of CT for falls in older people.[62][63]

Cause of falls

In a person with frailty, falls are often multifactorial in origin, and their investigation and management needs to reflect this complexity. The UK Royal College of Physicians and British Geriatrics Society (BGS) both recommend that older people presenting with a fall (with or without a resulting fracture) should be assessed for reversible causes of the fall, and referred for a falls and bone health assessment.[1][40]

When investigating for cause of fall consider the following:

Is there a history of previous falls?

Is the history suggestive of a syncopal fall?

Is there any evidence of acute infection?

Have they sustained a traumatic injury?

Is there a postural drop in blood pressure?

Is there any evidence of cognitive impairment?

Are there medications that may increase the risk of falling?

Is there any sensory impairment?

Are there any problems with incontinence?

Assessment of falls

Due to the multi-faceted nature of falls in people with frailty, it may not be practical to address all aspects on initial presentation to the emergency department. The BGS acknowledges that falls can be managed along an appropriate more practical timeline over 24-48 hours and proposes the following:[40]

Initial assessment:

Exclude medical illness associated with fall

Consider ECG, lying and standing blood pressure, septic screen, and assess fluid balance

Exclude acute injury (e.g., hip fracture)

Consider x-ray and/or CT

Within 3-4 hours:

Assess for cognitive impairment and delirium

Consider 4 As test (4AT) or brief confusion assessment method (bCAM). See Acute hospital setting: delirium for more details

Assess gait and balance

Feet and footwear assessment, current mobility, and need for aids

Stratify risk for safe discharge

Safety in the home and escalation plans if falls again

Within 24-48 hours - multidisciplinary assessment:

Bladder and bowel assessment for incontinence

Assessment for malnutrition

Assessment for functional decline and frailty

Activities of daily living assessment

Home environment modifications

Occupational therapy review

Depression screen

Depression and anxiety screening tools

Hearing and vision assessment

Medication review

Structured medication review

Resources

Key points

Delirium is a common presentation in people with frailty.

Early recognition and diagnosis is crucial.

Assess using a validated screening tool within 24 hours of hospital admission.

Quickly identify and manage potential causes.

If difficult to distinguish between delirium, dementia or delirium on top of dementia, manage the delirium first.

Provide a multicomponent intervention tailored to the patient’s needs.

Risk factors for delirium

Delirium is defined as 'a disturbance in attention and awareness that is accompanied by an acute loss in cognition and cannot be better accounted for by a pre-existing or evolving dementia'.[64] It is a common presentation in people with frailty.[65] One large meta-analysis found that people with frailty have an approximately 3-fold risk of delirium compared to people without frailty, indicating the value of early screening for frailty and prompt interventions to help reduce rates of delirium.[66]

Risk factors for delirium include:[67]

Physical frailty

Age >65 years

Dementia

Acute illness

Hip fracture.

Delirium carries a high risk; mortality in people presenting with delirium is twice as high as in those with similar conditions without delirium.[68] Unfortunately delirium is still often a missed diagnosis.[69]

Presentation of delirium

Typical presentations of delirium include increased confusion, reduced mobility or hallucinations. Different clinical subtypes of delirium have been identified.[40][70][71][72] These include:

Hyperactive delirium - may have heightened arousal with restlessness, agitation, hallucinations, or inappropriate behaviour.

Hypoactive delirium - may display lethargy, reduced motor activity, incoherent speech, or a lack of interest.

Mixed delirium - a combination of both hyper and hypoactive signs or symptoms.

Delirium may be an initial presenting feature in people with frailty or it may develop during a hospital admission. For this reason, in the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends screening people at risk for delirium within 24 hours of hospital admission and then observing them at least daily for fluctuations indicative of delirium.[73]

Validated screening tools for assessing patients in the acute setting include:

In ICU settings or in recovery after surgery, NICE recommends using:[73]

The Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU) or

The Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist (ICDSC)

See more on preventing delirium in the sections: 'Acute hospital setting: deconditioning' and 'Acute hospital setting: preventing delirium'.

Investigation and management of delirium

Once delirium is identified it is important to rapidly establish and manage potential causes. Acute, life threatening causes should be excluded as a priority such as:[75]

Hypoxia

Low blood glucose

Hypotension

Drug intoxication or withdrawal, including alcohol withdrawal

Other investigations include:

Full blood count, electrolytes, renal function, thyroid function tests, liver function tests, calcium, glucose, CRP, folate, and vitamin B12

Blood cultures (if bacteraemia is suspected)

Urine culture

Bladder scan for urinary retention

Chest x-ray

More advanced non-routine investigations such as CT head may be needed, depending on specific clinical findings.[75]

Check for and treat any reversible causes of delirium, for example:[73]

Pain

Infection

Poor nutrition

Constipation

Dehydration

Medications

Ask about recently prescribed medications, especially opioid analgesics, anxiolytics, sedatives, antipsychotics, or medications with strong anticholinergic properties.

Consider deprescribing and calculating a total anticholinergic burden score.

Immobility

Poor sleep

Sensory impairment (e.g., ear wax or loss of glasses).

The mnemonic PINCH ME may be helpful in determining the underlying causes of delirium:[76]

P - pain

I - infection

N - nutrition

C - constipation

H - hydration

M - medication

E - environment

It is common for multiple contributing causes to be found.

Initially manage patients with delirium with non-pharmacological treatment when possible:[73]

Reduce disorientation by providing a well-lit room, with a clock and calendar visible (e.g., on the wall).

Encourage and facilitate family, friends, and carers to visit the patient.

Use verbal and non-verbal techniques to de-escalate conflict and distress.

If non-pharmacological treatments prove ineffective, and the patient is distressed or considered a risk to themselves or others, short-term (often only 1-2 days is required) antipsychotic or sedative drugs may be considered, but only as a last resort. Any new antipsychotic prescribed for this purpose must be regularly reviewed, and discontinued as soon as practical.

NICE recommends short-term use of haloperidol (usually for less than a week), but it is not suitable in all patients and must never be used in patients with Parkinson’s disease or in patients with Lewy body dementia.[73] Check for all contraindications.

Take particular care to monitor and regularly review older people with frailty when prescribing haloperidol for acute delirium. They are particularly at risk of neurological and cardiac adverse effects.[77]

A baseline ECG and correction of electrolyte abnormalities is recommended before starting haloperidol.

Prescribe at the lowest dose for the shortest length of time possible.

During treatment, cardiac and electrolyte monitoring is recommended, and monitoring for extrapyramidal adverse effects.

The evidence on the efficacy of antipsychotics for delirium is inconclusive, and hospital protocols may vary.[75] Follow your local hospital protocol for choice of medication.

Always start at the lowest dose for antipsychotic drugs and titrate carefully according to symptoms.[73] Only ever use oral or intramuscular medication (never intravenous) for this purpose.

Delirium can be distressing for families to witness, so information on delirium can be helpful. The Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) has some useful patient information leaflets that can help keep families informed so they understand what is happening and how they can work together with the clinical team to help the patient get back to their usual self. SIGN: Delirium Opens in new window

If underlying possible causes have been managed effectively but delirium persists, repeat the screening for potential reversible causes. If, despite this, delirium is still present then the patient should be assessed for potential dementia.[73]

Practically this might be better followed up in the community after discharge, in this case it should be communicated to the GP in the discharge summary to consider referral for formal memory assessment services as an outpatient.

Resources

Key points

People with frailty:

Have better outcomes if they have a Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) during admission.

Are at significant risk of deconditioning in hospital.

Are at significant risk of developing delirium in hospital.

Are at significant risk of malnutrition and its complications.

Keep patients with frailty moving, hydrated and adequately nourished.

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment

Whether an acute unplanned admission or an elective admission, people with frailty are at higher risk of adverse health outcomes even after a short stay (<72 hours).[78]

One Cochrane review found that older patients are more likely to be alive and living in their own homes after discharge if they received a CGA on admission to hospital.[36] In the UK, the accepted standard for assessing people with frailty is the CGA developed by British geriatricians and endorsed by the NHS. BGS: comprehensive geriatric assessment toolkit for primary care practitioners Opens in new window

The CGA is an evidence-based multidimensional holistic assessment tool that leads to formulation of a plan to address areas of concern to the individual, and arrange interventions in support of that plan. The term 'assessment' can be misleading as it is a form of integrated care and an example of a complex intervention. It is sometimes referred to as a geriatric evaluation, management and treatment (GEMT) intervention. BGS: comprehensive geriatric assessment toolkit for primary care practitioners Opens in new window The assessment covers a number of domains including:

Physical

Functional, social and environmental

Psychological components

Medication review

While in hospital, deconditioning and delirium are significant risks to people with frailty and risks that can be mitigated. Older adults living with frailty experience adverse health outcomes from hospital admission, these can be attenuated using CGA.[40] Many hospitals now have dedicated frailty units, elderly care wards and orthogeriatric teams, regardless of the admitting specialty, once frailty is identified a holistic approach incorporating a patients priorities in the context of the acute medical problem are essential for geriatric emergency care.[40]

Prolonged bed rest can rapidly lead to substantial loss of muscle strength, power and aerobic capacity, even in healthy adults and resultant deconditioning.[79]

Deconditioning has been defined as a complex process of physiological change following a period of inactivity, bedrest or sedentary lifestyle, resulting in functional losses.[80] These losses can include decline in mental status, degree of continence and a person's ability to accomplish usual activities of daily living.[80]

Deconditioning is a major risk for older people with frailty admitted to hospital.[28]

A third will experience a functional decline during their admission.[33]

A number of initiatives have looked into strategies to help prevent deconditioning.

In the UK, EndPJparalysis is one example of such a campaign, encouraging healthcare professionals to ensure those who are able get up, get dressed and mobilise each day. #EndPJparalysis Opens in new window

‘Sit up, get dressed and keep moving’ is another initiative, supported by the BGS, aimed at preventing deconditioning. BGS: ‘sit up, get dressed and keep moving! Opens in new window

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Sit up, get dressed, Keep movingBritish Geriatrics Society. ‘Sit Up, Get Dressed and Keep Moving!’. Jul 2020 [internet publication] [https://www.bgs.org.uk]; used with permission [Citation ends].

People with frailty who are admitted to hospital are at increased risk of developing delirium during their stay, even if it was absent on initial presentation.[73] NICE guidance recommends that a multicomponent intervention, tailored to an individual patient's needs, should be implemented to prevent delirium.[73] This includes:[73]

Addressing cognitive impairment

Ensuring hydration

Managing constipation

Monitoring oxygen and addressing any hypoxia

Monitoring for infection

Avoiding unnecessary catheterisation

Encouraging mobilisation

Addressing pain

Reviewing medication

Addressing nutrition

Addressing any sensory problems

Encouraging good sleep hygiene

Around 1 in 3 patients admitted to an acute care hospital will be malnourished or at risk of malnutrition.[81] Malnutrition is associated with increased mortality and morbidity including:[82]

Loss of muscle

Higher rates of infection

Impaired wound healing

Longer hospital stay

In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends that all hospital inpatients should be screened for malnutrition on admission.[83] Repeat weekly throughout the hospital stay.

The Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST) is a validated screening tool from the Malnutrition Advisory Group, a standing committee of the British Association for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (BAPEN) that can be used to identify at-risk adults. It uses the following to calculate an overall risk of malnutrition and help guide management: BAPEN: the 'MUST' toolkit Opens in new window

BMI

Percentage weight loss

Current acute illness

NICE guidance recommends that in the hospital setting, a patient’s nutritional requirements should be decided by healthcare professionals trained in nutritional support.[83]

Oral nutritional supplements (ONS) are:

Indicated in people who are malnourished (have lost more than 10% of their weight within the last 3-6 months or their BMI is less than 18.5 kg/m²) or for people who have very poor oral intake due to an acute illness.[83]

Cost effective when used in hospital.[84]

Resources

Ever greater numbers of older people are being considered suitable to undergo elective and emergency surgery.[40] It is important to consider the possibility of an impact of reduced physiological reserve, multimorbidity and geriatric syndromes at all stages of the surgical pathway.[40]

There is increasing evidence that Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) in the perioperative setting improves outcomes.[85][86][87]

There is also emerging evidence around ‘prehabilitation’ to optimise physical function and psychological state prior to elective surgery.[88] The UK Centre for Perioperative Care has developed guidance in conjunction with the British Geriatric Society for the care of people with frailty undergoing elective or emergency surgery.[89]

Resources

Centre for Perioperative Care: Perioperative care of people living with frailty Opens in new window

This guideline includes a diagram for a frailty pathway.

ERAS® Society: guidelines for perioperative care in elective colorectal surgery Opens in new window

BGS: Proactive care of older people undergoing surgery (POPS service) Opens in new window

Key points

Polypharmacy is a risk for people living with frailty.

Use a validated tool for medicines optimisation, ideally a structured medication review (SMR).

Polypharmacy

Polypharmacy itself is a defined risk factor for developing frailty.[90] The definition of polypharmacy varies across different sources, but is commonly defined as the routine use of five or more medications.[91][92] An alternative descriptive definition is the use of medications not clinically indicated.[93] Appropriate polypharmacy is present when all medications are:[92][94]

Prescribed for the purpose of achieving specific objectives agreed with the patient

Achieving therapeutic objectives, or likely to in the future

Optimised to minimise the risk of adverse drug reactions

Taken as intended

Inappropriate polypharmacy occurs when one or more medications are no longer needed, either because:[92][94]

There is no evidence based indication

The dose is unnecessarily high

The therapeutic objectives are not met

One, or the combination is causing or putting the patient at high risk of adverse drug reactions

The patient is not willing or able to take them as intended

Older people with frailty have an inherent risk of polypharmacy due to the need to manage multimorbidity. In turn, they are more likely to have reduced kidney function and reduced physiological reserve, putting them at higher risk of adverse drug reactions.[95] An estimated one-third of emergency department presentations among older people involve adverse drug reactions.[96] There is also a risk of developing polypharmacy during an acute admission, as medications are added to treat the current clinical situation causing an iatrogenic cascade.[97]

Structured medication review

Despite increasing research, it is unclear whether any interventions to improve appropriate polypharmacy result in clinically significant improved outcomes.[98][99] However, one Cochrane Review concluded that medication reviews in adults in hospital are likely to reduce hospital readmissions and may reduce emergency department contacts.[100] NHS England recommends that all patients identified as having severe frailty and those with polypharmacy (>10 medications) should have an SMR. Key components of an SMR include:[101][102]

Shared decision-making underpinning the conversation

Personalised approach – tailored to the patient

Safety – balance of benefit and risk of current treatment and starting new medications

Effectiveness – all medication must be effective

Anticholinergic burden

Drugs with anticholinergic properties are known to cause adverse effects such as a dry mouth, blurred vision, constipation and urinary retention. In older people with frailty, drugs with anticholinergic effects may also contribute to cognitive decline, loss of functional capacity, an increased risk of dementia, and mortality.[103][104] Many drugs that are not in the class of anticholinergics also have anticholinergic effects including commonly prescribed medications such as antidepressants, antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, antihistamines, and drugs used for Parkinson’s disease.[103][105]

Anticholinergic burden (ACB) refers to the cumulative effect of taking one or more medications with anticholinergic activity on an individual.[103]

Many tools are available to calculate an ACB score, which can be useful when assessing pharmacological risk at medication review.[103]

An ACB score of 3 or more may increase the risks of cognitive impairment, functional impairment, falls and mortality in older adults.[104][106]

Tools such as an ACB calculator can help facilitate decisions to deprescribe or switch medications with anticholinergic side effects where possible. One Cochrane review found insufficient evidence to conclude on anticholinergic burden reduction interventions and their effect on cognitive outcomes in older adults with or without cognitive impairment.[103][107]

Consider tapering when stopping anticholinergic medications to avoid withdrawal side effects such as nausea and sweating.[108]

Consider whether a non-pharmacological approach may be a helpful alternative.[108]

Deprescribing

Frailty can mark the point at which the evidence base for secondary prevention often ceases. As part of a pragmatic approach to deprescribing in older people living with moderate to severe frailty, and as part of the CGA, it is common to balance the benefits and risks of stopping medications aimed at secondary prevention in partnership with the patient and their carer or family.[109] There is little evidence for efficacy of medications like statins especially in the severe frailty cohort.[110] A structured medication review should be done to systematically review all medications. Medication prescription aids can be used to help reduce unnecessary use of prescription medications, these include:[111]

STOPP/START criteria: The Screening Tool of Older People's Prescriptions (STOPP) and the Screening Tool to Alert Right Treatment (START) aims to avoid omissions and inappropriateness in prescribing and has been validated by a European expert panel using the Delphi consensus process.[112]

The AGS Beers Criteria® is produced and regularly reviewed by the American Geriatrics Society (AGS) and updates the original version first published in 1991.[113][114] It lists potentially inappropriate medication for older adults across various settings. The AGS states that although the AGS Beers Criteria® may be used internationally, they have been specifically designed for use in the United States.[113]

Some commonly used medications are potentially inappropriate for use in people with frailty. Consider the appropriateness of the medications outlined in the table below.[112]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Medications that may need to be stopped (adapted from BMJ Learning module on frailty)Created by BMJ Learning; used with permission [Citation ends].

In addition to the medication considerations in the table above, take care if initiating antihypertensives in older people with frailty. There is an increased risk of postural hypotension, so this may increase the risk of falls and fracture, particularly in the first few weeks after starting the medication.[115] In practice, check a lying and standing blood pressure before starting antihypertensive medication in older people with frailty and consider rechecking 2 weeks after starting the medication (based on expert opinion). The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends to consider antihypertensive drug treatment in addition to lifestyle advice for people aged over 80 years with stage 1 hypertension if their clinic blood pressure is over 150/90 mmHg, and to use clinical judgement for people with frailty or multi-morbidity.[116]

Resources

Key points

Establish if a 'Do Not Attempt Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation' (DNACPR) decision and/or advance care plan/directive is already in place. If not, consider discussion if appropriate.

Establish a clear escalation plan, including ceiling of intervention (sometimes called 'ceiling of care').

Effective communication with patients and family is essential to achieve shared-decision making.

People living with frailty or multi-morbidity may have previously had discussions in primary care or during prior hospital admissions regarding future care planning. On admission to hospital with an acute condition, it is important to establish if a person already has in place one or more of a DNACPR decision; an advance care plan, such as a Recommended Summary Plan for Emergency Care and Treatment (ReSPECT) form; or an advance care directive. If not, consider whether the hospital admission represents a change in a person's state of frailty that might represent an opportunity to discuss future care plans. Any resuscitation or advance care directives should be taken into account when determining the ceiling of intervention. A senior clinician along with the medical team determines the highest level of intervention deemed appropriate in alignment with patient and family wishes. This typically results in one of three pathways:[117]

Full escalation

Limited escalation

Maintenance of current care with option of palliative care initiation

Do Not Attempt Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (DNACPR)

The likelihood of recovery from CPR is very varied depending on a patient's condition and the circumstances surrounding the clinical situation, but the overall proportion of people surviving CPR is relatively low.[118] Resuscitation Council UK: Epidemiology of cardiac arrest guidelines Opens in new window In addition, attempting CPR has potential for adverse effects including rib and sternal fractures.[119]

The British Medical Association (BMA), Resuscitation Council UK, and the Royal College of Nursing (RCN) provide guidance regarding anticipatory decisions about whether or not to attempt resuscitation. Resuscitation Council UK: decisions relating to cardiopulmonary resuscitation Opens in new window

Conversations about dying and CPR are very sensitive and potentially distressing for patients and their relatives. The guidance helps healthcare professionals approach these discussions.

The guidance covers legal and ethical principles that inform CPR decisions.

CPR decisions are not legally binding, unlike advance decisions to refuse treatment (ADRT) which may include decisions around CPR.

Although the core principles are the same for all people, individual and clinical circumstances vary so it is essential that CPR discussions and decisions are made on an individual basis. RCGP: Joint statement on advance care planning Opens in new window

It should be noted that CPR decisions are guided by law which differs between countries, including between England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. Follow the appropriate legislation in your region.

Triggers for a discussion or a review of a CPR decision include any request from the person themselves, or those close to them, and also any substantial change in the patient’s clinical condition. It is always better to have conversations about future planning when not in crisis, but an admission to hospital often represents a change in a person's condition so is often a time to initiate or review discussions around resuscitation status.

Effective communication is essential.

Effective communication with patients and family is essential to achieve shared-decision making.[48]

Information on risk should be communicated clearly taking into account patient and family wishes.

It is important that the decisions are clear and understood by the patient if they have capacity and by all other parties involved.

Include relatives or those close to the patient, unless the patient has requested confidentiality.

Provide information and check they have understood what has been explained.

Broader discussions regarding goals of care can be useful to put decisions around CPR in context. Following an advance care plan framework such as ReSPECT can help frame these sensitive discussions.

Any documentation around DNACPR should be shared with the relevant local ambulance service.

Advance care plans

Advance care planning is a voluntary process. The process should be a person-centred discussion between a person and their healthcare provider about the individual's preferences and priorities for future care. NHS England: universal principles for advance care planning (ACP) Opens in new window Conversations can be over a period of time and revisited with whoever the person wishes to involve. When done well, people feel they have had the opportunity to plan for their future care with a focus on what matters most to them. NHS England: universal principles for advance care planning (ACP) Opens in new window

The legal framework around advance care planning varies in different countries. In the UK, outputs of discussions around advance care planning may include: NHS England: universal principles for advance care planning (ACP) Opens in new window

An advance statement – wishes, preferences and priorities. May include nomination of a named spokesperson

An advance decision (or directive) to refuse treatment (ADRT)

Nomination of a lasting power of attorney (LPA) for health and welfare

Context-specific treatment recommendations - could include emergency care and treatment plans, treatment escalation plans or cardiopulmonary resuscitation decisions

An advance statement is not legally binding in the UK but can be used by the LPA and healthcare professionals to help guide decision making if the person subsequently loses capacity. ADRTs and LPAs are legally binding provided they are valid and applicable.

Tools to frame and support such conversations include:

Treatment escalation plans (TEPs)

Anticipatory clinical management plans

Recommended summary plans for emergency care and treatment (ReSPECT)

Deciding right

Other local tools

Use a tool that is recognised in your local area.

ReSPECT, developed by the Resuscitation Council UK, has been adopted in a number of NHS Trusts across England. Resuscitation Council UK: ReSPECT for healthcare professionals Opens in new window Going through the ReSPECT process creates a summary of personalised recommendations for an individual's clinical care, producing documentation which can be helpful in cases where they are unable to express their wishes or do not have capacity. It covers emergencies such as cardiac events and attempts at CPR but is not limited to this. The process of completing a ReSPECT form is designed to capture a patient's preferences informed by advice from the healthcare professional based on their clinical judgement. A conversation to discuss a ReSPECT form should be done by a healthcare professional who is trained to do so. The Resuscitation Council UK recommends to: Resuscitation Council UK: ReSPECT for healthcare professionals Opens in new window

Discuss and reach a shared understanding of the person’s current state of health and how it may change in the foreseeable future.

Identify what is important to the person in relation to goals of care and care in the event of a future emergency.

Use the ReSPECT form to record an agreed focus of care (either towards life-sustaining treatments or towards prioritising comfort over efforts to sustain life).

Make and record shared recommendations about specific types of care and realistic treatment that should/shouldn’t be given, and explain sensitively recommendations about treatments that would clearly not work in their situation.

Make and record a shared recommendation about whether or not CPR is recommended.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Example of a ReSPECT formResuscitation Council UK: ReSPECT for healthcare professionals; used with permission [Citation ends].

Advance directives

An advance directive (sometimes known as advance decision to refuse treatment (ADRT) or living will) is a decision a person can make to refuse a specific treatment in the future. In order for it to be valid in UK law, it needs to be:

written down

signed by the person; and

witnessed.

In the UK, it is a legally binding document that can take precedence over a ‘best interests decision’ if it:

complies with the Mental Capacity Act 2005

is valid; and

is applicable to the clinical situation.

Some things cannot be included in an advance directive, for example a person cannot: Age UK: advance decisions, advance statements and living wills Opens in new window

Choose to refuse essential care for example nursing care, pain relief, or keeping warm.

Choose to refuse the offer of food or drink by mouth.

Ask for anything unlawful (e.g., euthanasia or help to end your life).

Demand specific treatment. Healthcare professionals do not have to give treatment considered clinically unnecessary, futile, or inappropriate.

Refuse treatment for a mental health disorder if you meet relevant criteria to be detained under the Mental Health Act 1983.

If you practice outside the UK, ensure you check the legal status under local law.

An ADRT is legally binding, so if a patient has stated they do not want CPR but they require an operation, the surgeon and/or anaesthetist should have a discussion with the patient about temporarily suspending the ADRT as elements of CPR may be needed during or after the operation.[120]

Escalation plans

Once a person is admitted to hospital, it is important to have a clear escalation plan which takes the shared decisions into account. This allows all healthcare professionals involved in an individual’s care to have a clear understanding of management options should the person deteriorate.

An escalation plan should include:[121]

Resuscitation status (i.e., DNACPR decision).

Any advance care plans made, such as ReSEPCT forms, or legally binding advance decisions.

Ceiling of intervention (often called ceiling of care), such as suitability for intubation or intensive care admission.

Take account of any advance care plans, including legally binding advance directives. Be guided by your conversations with the patient about their individual wishes in order to help them reach an informed decision about the likely benefit-risk of higher intensity interventions.[121]

Mental capacity

In some situations, for example a patient with learning difficulties, dementia or delirium or during acute illness, a patient may lack the mental capacity to make decisions about escalation plans. In these cases it is important to:

Assess and document mental capacity (the ability to make a specific decision at the time that the decision needs to be made).[122]

Follow the appropriate legislation in your region.

In England and Wales, health professionals must comply with the 2005 Mental Capacity Act.[123] Assessments should follow the principles in the Act.[123]

If a patient is assessed as lacking mental capacity, consult with their next of kin to make ‘best interests’ decisions, bearing in mind what is known about the patient’s own previously expressed preferences.[123]

According to the 2005 Mental Capacity Act in England and Wales, if a patient is ‘unbefriended’ (i.e., has nobody to represent their best interests who is not paid to provide care) and a decision is not time-critical, an independent mental capacity advocate (IMCA) should be sought to perform this role.[124]

Resources

Tools to help frame and document discussions around ACP:

Resuscitation Council UK: ReSPECT for healthcare professionals Opens in new window

The Gold Standards Framework: thinking ahead Opens in new window

Advance directives:

NHS: advance decision to refuse treatment (living will) Opens in new window

Compassion in dying: living will (advance decision) Opens in new window

DNACPR:

Mental capacity:

Office of the Public Guardian: Mental capacity act code of practice Opens in new window

Scottish Government: adults with incapacity: guide to assessing capacity Opens in new window

NICE guidance: decision-making and mental capacity Opens in new window

NICE quality standard: decision making and mental capacity Opens in new window

SCIE: Independent Mental Capacity Advocate (IMCA) Opens in new window

Key points

Frailty is associated with worse health outcomes and ‘system’ outcomes such as avoidable hospital admission.

Poor health and system outcomes may be reversible or preventable.

Screen all adults over 65 for frailty on an opportunistic basis.

Use a validated tool like the electronic frailty index (eFI) for risk stratification.

Use clinical judgement and the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) to confirm the level of frailty.

Where frailty is identified, offer evidence based intervention such as comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA).

Early identification of frailty

People with frailty have worse health outcomes; early identification of a patient living with frailty allows for a more holistic approach, with targeted interventions such as CGA that can improve outcomes (see Community setting: Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) for more detail).[125][126]

Video on the importance of identifying people living with frailty in the community.

Many frailty screening tools are available and are established as predictors of adverse outcomes such as functional decline, hospital stays and mortality.[127][128][129] GPs, district nurses, paramedics, pharmacists and other healthcare professionals working in the community are in an ideal position to help identify frailty early and opportunistically at routine healthcare appointments as well proactively through population health management and risk stratification.[130]

The task force of the International Conference of Frailty and Sarcopenia Research strongly recommends that all adults over the age of 65 should be offered screening for frailty using a validated rapid frailty instrument suitable to the specific setting or context.[31]

Any healthcare encounter offers an opportunity to screen for frailty.

The task force emphasises the importance of training health practitioners in frailty screening.

The British Geriatrics Society recommendations for the community setting include to assess older people for the presence of frailty during all encounters with health and social care professionals.[55] NHS Rightcare frailty toolkit recommends the identification of frailty and stratification of the population living with frailty by needs rather than age.[131]

In the UK, the eFI has been embedded into the vast majority of general practices to help screen for frailty. NHS England: electronic frailty index Opens in new window

The eFI is calculated using existing Read Codes within a patient's health record. It uses a ‘cumulative deficit’ model to measure frailty based on these.

It has been widely embedded into GP practices across the UK to help with identification of patients with frailty.

Although the generated score highlights if a patient is at risk of mild, moderate or severe frailty based on their existing diagnoses and medications, it is a mathematical model, still very much reliant on clinical confirmation, that acts as a prompt for the healthcare professional to further assess for frailty.

Tools to assess frailty

Whenever frailty is suspected (e.g., based on a high eFI score), a clinical assessment should be done using a validated tool to confirm and stratify the level of frailty.

Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS)

The British Geriatrics Society recommends a tool such as the CFS to identify the level of frailty in older people at risk. British Geriatric Society: Silver book II: geriatric syndromes Opens in new window Be aware that the CFS is not validated for use in people younger than 65 years or in people with a learning disability. It is not suitable for use in people with stable long-term disabilities such as cerebral palsy. Dalhousie University: clinical frailty scale Opens in new window

Video outlining how to identify and assess people living with frailty

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Clinical Frailty ScaleAdapted from Dalhousie University. Clinical Frailty Scale version 2.0. 2020; used with permission [Citation ends].

The Clinical Frailty Scale App is a free downloadable tool published on behalf of NHS Elect, which presents the CFS as a series of nine questions with a ‘yes/no’ answer. The response to the questions identifies the level of frailty and provides a recommendation about how to approach the patient's care. It can be used in the community and in the acute setting, but in the acute setting it should be based on the patients capabilities two weeks prior to the hospital attendance/admission.[45]

Other tools to screen for frailty in the community include the gait speed test, PRISMA-7 and the timed get up and go test.

Gait speed test

The gait speed test has been used as a functional assessment in older people. Taking more than 5 seconds to walk 4 metres indicates frailty.[132][133]

PRISMA-7

The Program of Research to Integrate Services for the Maintenance of Autonomy (PRISMA)-7 was developed in Canada as a questionnaire screening tool to detect individuals with frailty in the community.[134]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: PRISMA-7. Yes-answers are given one point each; No-answers are given zero points. A score of three or above indicates frailtyHoffmann S et al. BMJ Open 2020;10:e038768; used with permission [Citation ends].

Timed get up and go test

A functional mobility evaluation where the assessor measures the time taken for an individual to:[135][136]

rise from seated,

walk 3 metres,

turn around,

walk back to the chair, and

sit back down.

This is relatively quick to perform with minimal equipment so is useful in the community, and has occasionally been used to screen for frailty.[137] Most healthy older adults can complete the test in 10 seconds or less. People who complete the test in 13.5 seconds or longer may be at greater risk of falls.[138]

Strategies following assessment

Identifying frailty allows the healthcare team to stratify older patients living with frailty according to their risk of adverse health outcomes and aid prognosis. Although not a rigid guide without further clinical assessment and discussion, the Clinical Frailty Scale helps assess which paradigm a person living with frailty is in and which types of intervention (curative or palliative) may be the priority.

Mild to moderate frailty - there is some evidence that certain lifestyle/behavioural interventions delay the onset of frailty, and slow its progression (see Community setting: living with frailty/ageing well).[139][140] Target these interventions, aiming to improve or reverse frailty status.[31]

Moderate to severe frailty - consider interventions to reduce unplanned hospital admissions for individuals with moderate to severe frailty, such as:[125]

Comprehensive geriatric assessments (see Community setting: comprehensive geriatric assessment)

Structured medication reviews (see Community setting: medication optimisation)

Falls prevention strategies (see Community setting: falls)

Severe to very severe frailty - consider discussions around what matters most to a person with severe frailty and have discussions around advanced care planning (see Community setting: advance care planning).

Resources

Key points

Be aware that it may be possible to slow down or even reverse the progression of frailty severity, particularly when an individual is at an early stage of frailty.

Screen for malnutrition.

Provide nutrition education specifically for people at risk of, or living with, frailty.

UK health departments recommend vitamin D supplements for people >65 years.

Consider advice on resistance and/or aerobic exercise, as this has been shown to improve muscle function.

Support strategies to encourage social inclusion to promote wellbeing (e.g., social prescribing and sign posting to community and voluntary services).

Preventing frailty

Frailty is not inevitable. In recent years, in the context of an ever-ageing population, there has been increased research into ‘ageing well’ or ‘healthy ageing’, which relates closely to preventing frailty. Healthy ageing is the process of developing and maintaining the functional ability that enables wellbeing in older age.[20] This has resulted in an increasing body of evidence for interventions to delay the onset of frailty, and slow its progression.[139][140]

Frailty can be viewed as a dynamic state that a person can transition both into, and out of.[30] An acute hospital admission can rapidly result in a transition from a ‘robust’ to a ‘frail’ state.[31] Conversely, keeping physically active can improve or reverse frailty status.[31]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cascade of functional decline from independence through frailty to disabilityDent, E et al. J Nutr Health Aging 23, 771–87 (2019) [based on concepts and findings from other studies]; used with permission [Citation ends].

Healthcare professionals (e.g., GPs, nurses, pharmacists, paramedics) can take advantage of regular interactions to offer an individual with, or at risk of, frailty advice on diet, exercise and lifestyle, which may delay or prevent increasing frailty severity.

Integrated/proactive care

The United Nations (UN) General Assembly declared 2021–2030 the UN Decade of Healthy Ageing, and asked World Health Organization (WHO) to lead the implementation.

WHO has identified four areas of action to foster healthy ageing:[20]

Age-friendly environments

Action to combat ageism

Integrated care

Long-term care

Many of the issues identified for an ageing population relate to frailty, and so these initiatives are relevant to both ageing and frailty. Strategies can be at a population, national, local and individual level. Part of the WHO initiative includes guidelines on integrated care for older people (ICOPE), which include GRADE evidence tables on nutrition, mobility and maintaining sensory capacity.[141] The focus is on reversing the declining trajectory of intrinsic capacity (frailty) and providing holistic, person-centred care. This diagram illustrates the concept that by taking a proactive or preventative approach to promote healthy ageing, you can improve intrinsic capacity/frailty.[142]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Integration of care services over a life course (FA: functional ability, IC: intrinsic capacity)Cesari M et al. BMJ Global Health 2022;7:e007778; used with permission [Citation ends].

In the UK, the NHS recognises the importance of ageing well and supporting people living with frailty; indeed supporting people to age well is part of the NHS long term plan.[143]

Diet

Undernutrition is associated with frailty, sarcopenia and poor health outcomes.[3] There is increasing interest in the potential of interventions to improve nutrition and weight loss associated with frailty, but evidence is scarce.[144]

The NHS RightCare initiative (informed by National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance, Getting it Right First Time (GIRFT) and AGE UK) recommends to:[131]

Routinely screen for risk of malnutrition across health and social services in people at risk of developing frailty.

Provide nutrition education specifically for people at risk of, or living with, frailty.

Different tools are available to help screen for malnutrition. In the UK, NICE and BAPEN recommend the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST) to identify people at risk of malnutrition. NICE: Nutrition support in adults Opens in new window BAPEN: the 'MUST' toolkit Opens in new window

The World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines on integrated care for older people (ICOPE) focus primarily on identifying and managing malnutrition. WHO recommends oral supplemental nutrition (ONS) with dietary advice for older people affected by undernutrition.[141][Evidence B]

People with reduced appetite:

People who have a reduced appetite are at risk of malnutrition, and it is important that the food and drinks they consume contain as much energy and protein as possible. BAPEN: the 'MUST' toolkit Opens in new window

Advice on food enrichment is available from the British Association for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. BAPEN: the 'MUST' toolkit Opens in new window

People with medium risk of malnutrition:

Ask people at medium risk of malnutrition to document their dietary intake for three days, and assess if this is adequate.[145]

This can be repeated at least every two to three months for people who live in their own homes, and monthly for those living in care homes.

Closer monitoring is recommended for people with inadequate oral intake or for whom there is clinical concern.

Give advice on a fortified diet plan:

For older people at risk of malnutrition, interventions based on fortification of their food can increase their protein and calorie intake.[146]

People identified as high risk of malnutrition:[83]

Refer older people at high risk of malnutrition to a dietician or other nutritional support team in the community

They can set goals regarding their nutrition, establish a care plan, and review the person on a monthly basis.

Likewise, current UK guidance focuses on treating malnutrition to provide oral or artificial nutrition support.[83] Oral nutritional supplements (ONS) are initiated by dieticians and should be considered for people who can swallow safely and are malnourished or at risk of malnutrition.[83]

In the community, ONS are generally used for longer periods of time than in hospital settings, often in patients with chronic conditions. In practice, dietary education in the form of written information leaflets for the older person or their carer, or referral to a dietitian when deemed appropriate may be offered with or without ONS. However, there is little evidence on whether ONS (with or without other nutritional support) are effective in reducing malnutrition specifically for older people with frailty.[147]

Regarding vitamin supplementation, the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) advises that all people >65 should take a daily supplement containing 400 international units (10 micrograms) of vitamin D throughout the year.[148][149] Follow your current national recommendations on indications for treatment doses of vitamin D.[150]

Research into specific diets is emerging but has not reached a threshold to be incorporated into guidance yet. Evidence suggests older adults consuming a Mediterranean diet (high in fruits, vegetables, fish, nuts, and olive oil) are less likely to develop sarcopenia.[151] Sarcopenia (loss of muscle mass, strength, and function) is closely associated with frailty, and interventions to target sarcopenia can help reduce frailty.[31]

Exercise

Frailty is associated with the accumulation of multiple health problems and physical activity is linked to improvements in several areas including mental health, cardiovascular and bone health.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Health benefits of physical activityNHS RightCare. Falls and Fragility Fractures Pathway. Nov 2017 [internet publication] [https://www.england.nhs.uk/rightcare]; used with permission [Citation ends].

Higher levels of physical activity in mid life can reduce the risk of frailty in later life.[10] In the UK, NHS guidance suggests that people with no health conditions that limit mobility should do a mixture of aerobic and strengthening exercises as highlighted in the table below.[152][153]