Otitis media with effusion (OME) is the presence of middle ear effusion with no signs and symptoms of acute infection (fever, ear pain, discharge from the ear, tympanic membrane bulging, and erythema).[2]Rosenfeld RM, Shin JJ, Schwartz SR, et al. Clinical practice guideline: otitis media with effusion (update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016 Feb;154(1 suppl):S1-41.

https://aao-hnsfjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1177/0194599815623467

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26832942?tool=bestpractice.com

It is predominantly a clinical diagnosis, consisting of symptoms and physical exam findings consistent with the presence of middle ear effusion (e.g., otoscopy/pneumatic otoscopy), and/or tympanometry.

OME may follow or precede acute otitis media (AOM) and the risk factors and presenting symptoms of both will overlap. However, it is important to differentiate OME from AOM because OME is not due to an acute infection and therefore should not be treated as such.[50]Lieberthal AS, Carroll AE, Chonmaitree T, et al. The diagnosis and management of acute otitis media. Pediatrics. 2013 Feb 25;131(3):e964-99.

https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/131/3/e964.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23439909?tool=bestpractice.com

While middle ear effusion is present in both conditions (and is a hallmark of both), symptoms and signs of acute inflammation are not present in OME. See Acute otitis media.

History

The signs and symptoms that support a diagnosis of OME vary with the age of the patient. Both children and adults may even be asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic.[2]Rosenfeld RM, Shin JJ, Schwartz SR, et al. Clinical practice guideline: otitis media with effusion (update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016 Feb;154(1 suppl):S1-41.

https://aao-hnsfjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1177/0194599815623467

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26832942?tool=bestpractice.com

Older children and adults

In older children and in adults, symptoms typically consist of hearing loss, aural fullness or pressure, and a feeling of ear blockage.[51]Schilder AG, Bhutta MF, Butler CC, et al. Eustachian tube dysfunction: consensus statement on definition, types, clinical presentation and diagnosis. Clin Otolaryngol. 2015 Oct;40(5):407-11.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmid/26347263

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26347263?tool=bestpractice.com

Young children

In young children, symptoms may be more subtle, depending on the age and language development of the child, including poor balance, poor school performance, and behavioural problems.[2]Rosenfeld RM, Shin JJ, Schwartz SR, et al. Clinical practice guideline: otitis media with effusion (update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016 Feb;154(1 suppl):S1-41.

https://aao-hnsfjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1177/0194599815623467

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26832942?tool=bestpractice.com

Ask if the symptoms have had an impact on the child’s home life or at school.[52]Farboud A, Skinner R, Pratap R. Otitis media with effusion ("glue ear"). BMJ. 2011;343:d3770.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21727164?tool=bestpractice.com

Parents may notice signs of poor hearing, such as the child not responding when being called. Ask about indistinct speech, delayed language development or inattention. A parent or carer may also describe behavioural problems or slow progress within an education setting.[52]Farboud A, Skinner R, Pratap R. Otitis media with effusion ("glue ear"). BMJ. 2011;343:d3770.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21727164?tool=bestpractice.com

Pre-lingual children

Pre-lingual children may exhibit signs of aural discomfort such as tugging or scratching the pinna. They may also present with imbalance and impaired gross motor skills, as OME can affect the peripheral vestibular system.[3]Waldron MN, Matthews JN, Johnson IJ. The effect of otitis media with effusions on balance in children. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2004 Aug;29(4):318-20.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15270815?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Cohen H, Friedman EM, Lai D, et al. Balance in children with otitis media with effusion. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1997 Dec 10;42(2):107-15.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9692620?tool=bestpractice.com

In infants, ask about the results of the newborn hearing screening. Infants and children may present after a failed hearing screen or during the work up of speech delay.

Chronic OME

Ask about the duration of symptoms. Chronic OME is effusion that is persistent for ≥3 months, either from the date of onset, if known, or from the date of first diagnosis of middle ear effusion.[53]Rosenfeld RM, Tunkel DE, Schwartz SR, et al. Clinical practice guideline: tympanostomy tubes in children (update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022 Feb;166(1_suppl):S1-55.

https://aao-hnsfjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1177/01945998211065662

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35138954?tool=bestpractice.com

[1]Simon F, Haggard M, Rosenfeld RM, et al. International consensus (ICON) on management of otitis media with effusion in children. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2018 Feb;135(1s):S33-9.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S187972961830005X

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29398506?tool=bestpractice.com

Risk factors

Patient and environmental factors can increase a child’s risk of OME. Risk factors for OME include:

Young age (i.e., 6 months to 4 years)[2]Rosenfeld RM, Shin JJ, Schwartz SR, et al. Clinical practice guideline: otitis media with effusion (update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016 Feb;154(1 suppl):S1-41.

https://aao-hnsfjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1177/0194599815623467

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26832942?tool=bestpractice.com

Recent or current upper respiratory tract infection[2]Rosenfeld RM, Shin JJ, Schwartz SR, et al. Clinical practice guideline: otitis media with effusion (update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016 Feb;154(1 suppl):S1-41.

https://aao-hnsfjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1177/0194599815623467

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26832942?tool=bestpractice.com

History of acute otitis media[2]Rosenfeld RM, Shin JJ, Schwartz SR, et al. Clinical practice guideline: otitis media with effusion (update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016 Feb;154(1 suppl):S1-41.

https://aao-hnsfjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1177/0194599815623467

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26832942?tool=bestpractice.com

Craniofacial anomalies[2]Rosenfeld RM, Shin JJ, Schwartz SR, et al. Clinical practice guideline: otitis media with effusion (update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016 Feb;154(1 suppl):S1-41.

https://aao-hnsfjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1177/0194599815623467

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26832942?tool=bestpractice.com

Eustachian tube dysfunction[41]Matsune S, Sando I, Takahashi H. Insertion of the tensor veli palatini muscle into the eustachian tube cartilage in cleft palate cases. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1991 Jun;100(6):439-46.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2058982?tool=bestpractice.com

Genetic predisposition[2]Rosenfeld RM, Shin JJ, Schwartz SR, et al. Clinical practice guideline: otitis media with effusion (update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016 Feb;154(1 suppl):S1-41.

https://aao-hnsfjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1177/0194599815623467

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26832942?tool=bestpractice.com

[18]Casselbrant ML, Mandel EM, Fall PA, et al. The heritability of otitis media: a twin and triplet study. JAMA. 1999 Dec 8;282(22):2125-30.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/192180

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10591333?tool=bestpractice.com

[1]Simon F, Haggard M, Rosenfeld RM, et al. International consensus (ICON) on management of otitis media with effusion in children. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2018 Feb;135(1s):S33-9.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S187972961830005X

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29398506?tool=bestpractice.com

Group childcare attendance[2]Rosenfeld RM, Shin JJ, Schwartz SR, et al. Clinical practice guideline: otitis media with effusion (update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016 Feb;154(1 suppl):S1-41.

https://aao-hnsfjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1177/0194599815623467

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26832942?tool=bestpractice.com

[27]Nguyen LH, Manoukian JJ, Yoskovitch A, et al. Adenoidectomy: selection criteria for surgical cases of otitis media. Laryngoscope. 2004 May;114(5):863-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15126745?tool=bestpractice.com

Allergy[1]Simon F, Haggard M, Rosenfeld RM, et al. International consensus (ICON) on management of otitis media with effusion in children. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2018 Feb;135(1s):S33-9.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S187972961830005X

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29398506?tool=bestpractice.com

Environmental tobacco smoke[2]Rosenfeld RM, Shin JJ, Schwartz SR, et al. Clinical practice guideline: otitis media with effusion (update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016 Feb;154(1 suppl):S1-41.

https://aao-hnsfjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1177/0194599815623467

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26832942?tool=bestpractice.com

History of sinonasal disease

Nasopharyngeal malignancy or other mass

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease[1]Simon F, Haggard M, Rosenfeld RM, et al. International consensus (ICON) on management of otitis media with effusion in children. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2018 Feb;135(1s):S33-9.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S187972961830005X

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29398506?tool=bestpractice.com

Low socioeconomic status.[10]Zhang Y, Xu M, Zhang J, et al. Risk factors for chronic and recurrent otitis media-a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e86397.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3900534

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24466073?tool=bestpractice.com

Physical examination

Examine the patient’s upper respiratory tract and ears. Note any aural discharge. Persistent discharge, along with atypical otoscopy, may indicate a cholesteatoma, which requires urgent referral for specialist assessment of the ear, nose, and throat.[52]Farboud A, Skinner R, Pratap R. Otitis media with effusion ("glue ear"). BMJ. 2011;343:d3770.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21727164?tool=bestpractice.com

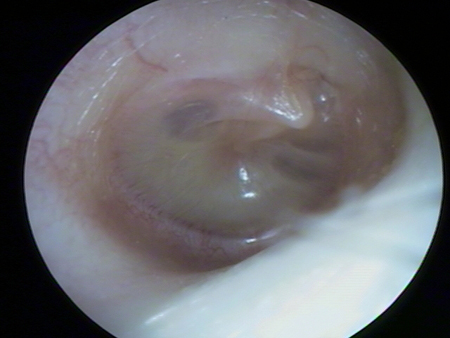

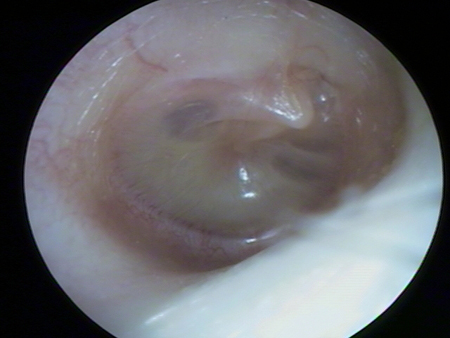

Examine both ears with an otoscope. The tympanic membrane may appear dark, with an amber, grey or blue hue. There may be bubbles or an air-fluid level.[2]Rosenfeld RM, Shin JJ, Schwartz SR, et al. Clinical practice guideline: otitis media with effusion (update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016 Feb;154(1 suppl):S1-41.

https://aao-hnsfjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1177/0194599815623467

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26832942?tool=bestpractice.com

In chronic OME (i.e. ≥3 months’ duration) the tympanic membrane may be retracted, in which case normal landmarks such as the short process of the malleus will appear more prominent.[50]Lieberthal AS, Carroll AE, Chonmaitree T, et al. The diagnosis and management of acute otitis media. Pediatrics. 2013 Feb 25;131(3):e964-99.

https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/131/3/e964.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23439909?tool=bestpractice.com

However, a normal looking tympanic membrane does not exclude OME unless pneumatic otoscopy is also normal.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Otoscopy of otitis media with effusion, showing air fluid levels or bubbles, with normal tympanic membrane landmarksFrom the personal collection of Dr Armengol [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Appearance of tympanic membrane in otitis media with effusion, showing bubbles and serous fluid in the inferior aspectFarboud A. BMJ. 2011;343:d3770 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Appearance of tympanic membrane in otitis media with effusion, showing bubbles and serous fluid in the inferior aspectFarboud A. BMJ. 2011;343:d3770 [Citation ends].

Initial investigations

OME is predominantly a clinical diagnosis. Pneumatic otoscopy should be performed, where possible, to confirm the presence of a middle ear effusion. Objective testing with tympanometry may be appropriate in certain patients for whom the diagnosis remains uncertain after the physical examination and pneumatic otoscopy. Audiological evaluation is needed to assess hearing loss in patients with chronic OME, or for OME of any duration in a child at risk of developmental sequelae (see Audiology section below).[2]Rosenfeld RM, Shin JJ, Schwartz SR, et al. Clinical practice guideline: otitis media with effusion (update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016 Feb;154(1 suppl):S1-41.

https://aao-hnsfjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1177/0194599815623467

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26832942?tool=bestpractice.com

Pneumatic otoscopy

Where possible, use pneumatic otoscopy to make the diagnosis in a patient with symptoms or signs suggestive of OME.[2]Rosenfeld RM, Shin JJ, Schwartz SR, et al. Clinical practice guideline: otitis media with effusion (update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016 Feb;154(1 suppl):S1-41.

https://aao-hnsfjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1177/0194599815623467

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26832942?tool=bestpractice.com

[1]Simon F, Haggard M, Rosenfeld RM, et al. International consensus (ICON) on management of otitis media with effusion in children. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2018 Feb;135(1s):S33-9.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S187972961830005X

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29398506?tool=bestpractice.com

The value of pneumatic otoscopy over standard otoscopy is that it can detect reduced tympanic mobility, which may be the only sign of effusion in a patient with OME.[2]Rosenfeld RM, Shin JJ, Schwartz SR, et al. Clinical practice guideline: otitis media with effusion (update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016 Feb;154(1 suppl):S1-41.

https://aao-hnsfjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1177/0194599815623467

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26832942?tool=bestpractice.com

It has a sensitivity and specificity of 94% and 80%, respectively, when compared to myringotomy.[54]Shekelle P, Takata G, Chan LS, et al. Diagnosis, natural history, and late effects of otitis media with effusion. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ). 2002 Jun;(55):1-5.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4781261

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12945555?tool=bestpractice.com

Make a diagnosis of OME based on reduced or restricted movement of the tympanic membrane; a complete absence of movement is not needed to be diagnostic.[2]Rosenfeld RM, Shin JJ, Schwartz SR, et al. Clinical practice guideline: otitis media with effusion (update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016 Feb;154(1 suppl):S1-41.

https://aao-hnsfjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1177/0194599815623467

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26832942?tool=bestpractice.com

Pneumatic otoscopy might be difficult to perform in young children, in part due to their narrow ear canals and also due to the tendency of young children to move as the investigation is being performed.[55]Venekamp RP, Schilder AGM, van den Heuvel M, et al. Acute otitis media in children. BMJ. 2020 Nov 18;371:m4238.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33208317?tool=bestpractice.com

Tympanometry

For patients who are difficult to examine and for patients in whom the diagnosis is uncertain following pneumatic otoscopy, perform tympanometry, where possible, to provide objective information on tympanic membrane mobility and middle ear compliance.[2]Rosenfeld RM, Shin JJ, Schwartz SR, et al. Clinical practice guideline: otitis media with effusion (update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016 Feb;154(1 suppl):S1-41.

https://aao-hnsfjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1177/0194599815623467

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26832942?tool=bestpractice.com

Tympanometric tracings (or curves) are classified into three main types:[2]Rosenfeld RM, Shin JJ, Schwartz SR, et al. Clinical practice guideline: otitis media with effusion (update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016 Feb;154(1 suppl):S1-41.

https://aao-hnsfjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1177/0194599815623467

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26832942?tool=bestpractice.com

[56]Onusko E. Tympanometry. Am Fam Physician. 2004 Nov 1;70(9):1713-20.

https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2004/1101/p1713.html

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15554489?tool=bestpractice.com

Type A indicates a normal ear with a low probability of effusion

Type B is the typical result to confirm OME (but a type B trace can also be seen with other conditions)

Type C suggests negative pressure, which may be related to OME. It should be correlated with other findings to confirm a diagnosis of OME.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Normal (type A) tympanogramFrom the collection of Erica R. Thaler; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Type B tympanogram; flat compliance curve demonstrates no movement of the tympanic membraneFrom the collection of Erica R. Thaler; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Type B tympanogram; flat compliance curve demonstrates no movement of the tympanic membraneFrom the collection of Erica R. Thaler; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Type C tympanogram, demonstrating a malfunctioning Eustachian tubeFrom the collection of Erica R. Thaler; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Type C tympanogram, demonstrating a malfunctioning Eustachian tubeFrom the collection of Erica R. Thaler; used with permission [Citation ends].

Audiology

In patients with chronic OME, or for OME of any duration in an at-risk child (see list below), perform an audiogram to establish baseline hearing levels and the impact of OME on the patient’s hearing. OME can cause no hearing loss through to a moderate conductive hearing loss.[2]Rosenfeld RM, Shin JJ, Schwartz SR, et al. Clinical practice guideline: otitis media with effusion (update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016 Feb;154(1 suppl):S1-41.

https://aao-hnsfjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1177/0194599815623467

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26832942?tool=bestpractice.com

Children who have the following conditions are considered to be at risk of developmental sequelae as a result of OME:[53]Rosenfeld RM, Tunkel DE, Schwartz SR, et al. Clinical practice guideline: tympanostomy tubes in children (update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022 Feb;166(1_suppl):S1-55.

https://aao-hnsfjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1177/01945998211065662

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35138954?tool=bestpractice.com

Permanent non-OME-related hearing loss

Speech and language delay or disorder

Autism-spectrum disorder

Genetic syndromes or craniofacial disorders associated with cognitive, speech, or language delays

Blindness or uncorrectable visual impairment

Cleft palate

Developmental delay

Intellectual disability, learning disorders, or attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Hearing loss can lead to speech delay, behavioural problems, and poor school performance in children, so it is important to identify. A hearing test should be performed that is appropriate for the patient’s age.[2]Rosenfeld RM, Shin JJ, Schwartz SR, et al. Clinical practice guideline: otitis media with effusion (update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016 Feb;154(1 suppl):S1-41.

https://aao-hnsfjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1177/0194599815623467

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26832942?tool=bestpractice.com

[1]Simon F, Haggard M, Rosenfeld RM, et al. International consensus (ICON) on management of otitis media with effusion in children. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2018 Feb;135(1s):S33-9.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S187972961830005X

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29398506?tool=bestpractice.com

Tests may include pure tone audiometry, speech audiometry, and bone-conduction.[1]Simon F, Haggard M, Rosenfeld RM, et al. International consensus (ICON) on management of otitis media with effusion in children. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2018 Feb;135(1s):S33-9.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S187972961830005X

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29398506?tool=bestpractice.com

The pure tone threshold average at 500, 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz may show hearing loss, typically of around 28 dB, but can be up to 50 dB in those with OME.[57]Roberts J, Hunter L, Gravel J, et al. Otitis media, hearing loss, and language learning: controversies and current research. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2004 Apr;25(2):110-22.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15083134?tool=bestpractice.com

[58]Dougherty W, Kesser BW. Management of conductive hearing loss in children. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2015 Dec;48(6):955-74.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26360369?tool=bestpractice.com

Consider any concerns from the parent or carer reporting the hearing loss. Severe hearing loss may indicate pathology other than or in addition to OME, such as congenital sensorineural hearing loss (genetic or non-genetic), inner ear malformations, and ossicular chain abnormalities, and should be appropriately investigated.

Developmental abnormalities or behavioural problems may affect the results of a routine hearing test, in which case referral to an otolaryngologist or audiologist may be required.[2]Rosenfeld RM, Shin JJ, Schwartz SR, et al. Clinical practice guideline: otitis media with effusion (update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016 Feb;154(1 suppl):S1-41.

https://aao-hnsfjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1177/0194599815623467

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26832942?tool=bestpractice.com

In infants with OME who fail a newborn hearing screen, follow-up is important to ensure that hearing is in fact normal once the OME resolves.[2]Rosenfeld RM, Shin JJ, Schwartz SR, et al. Clinical practice guideline: otitis media with effusion (update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016 Feb;154(1 suppl):S1-41.

https://aao-hnsfjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1177/0194599815623467

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26832942?tool=bestpractice.com

The results of hearing tests may influence the management plan.

Other investigations

In patients with chronic or recurrent OME, refer to otolaryngology for consideration of nasal endoscopy to assess for signs of chronic rhinosinusitis, as chronic rhinosinusitis with and without nasal polyposis has been associated with an increased risk of OME.[24]Finkelstein Y, Ophir D, Talmi YP, et al. Adult-onset otitis media with effusion. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994 May;120(5):517-27.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8172703?tool=bestpractice.com

[26]Parietti-Winkler C, Baumann C, Gallet P, et al. Otitis media with effusion as a marker of the inflammatory process associated to nasal polyposis. Rhinology. 2009 Dec;47(4):396-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19936366?tool=bestpractice.com

As a secondary investigation, nasopharyngeal endoscopy may be helpful in children for whom there is concern about concurrent nasal obstruction or prolonged unilateral OME to identify adenoid hypertrophy (providing that they are tolerant of the examination). Consider this more routinely in areas of high HIV prevalence due to the associated increased risk of nasopharyngeal anomalies, such as lymphoma.[1]Simon F, Haggard M, Rosenfeld RM, et al. International consensus (ICON) on management of otitis media with effusion in children. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2018 Feb;135(1s):S33-9.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S187972961830005X

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29398506?tool=bestpractice.com

In adults, refer to otolaryngology for consideration of nasopharyngeal endoscopy to assess the area by the torus tubarius (fossa of Rosenmueller), particularly if the effusion is unilateral.[24]Finkelstein Y, Ophir D, Talmi YP, et al. Adult-onset otitis media with effusion. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994 May;120(5):517-27.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8172703?tool=bestpractice.com

[59]Neel HB 3rd. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma: diagnosis, staging, and management. Oncology (Williston Park). 1992 Feb;6(2):87-102.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1532503?tool=bestpractice.com

Look for signs of nasopharyngeal carcinoma on nasal endoscopy as it is associated with adult-onset OME. The rate of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in adults with OME is around 5% to 6%.[28]Ho KY, Lee KW, Chai CY, et al. Early recognition of nasopharyngeal cancer in adults with only otitis media with effusion. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008 Jun;37(3):362-5.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19128640?tool=bestpractice.com

[24]Finkelstein Y, Ophir D, Talmi YP, et al. Adult-onset otitis media with effusion. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994 May;120(5):517-27.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8172703?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Appearance of tympanic membrane in otitis media with effusion, showing bubbles and serous fluid in the inferior aspectFarboud A. BMJ. 2011;343:d3770 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Appearance of tympanic membrane in otitis media with effusion, showing bubbles and serous fluid in the inferior aspectFarboud A. BMJ. 2011;343:d3770 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Type B tympanogram; flat compliance curve demonstrates no movement of the tympanic membraneFrom the collection of Erica R. Thaler; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Type B tympanogram; flat compliance curve demonstrates no movement of the tympanic membraneFrom the collection of Erica R. Thaler; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Type C tympanogram, demonstrating a malfunctioning Eustachian tubeFrom the collection of Erica R. Thaler; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Type C tympanogram, demonstrating a malfunctioning Eustachian tubeFrom the collection of Erica R. Thaler; used with permission [Citation ends].