Recommendations

Key Recommendations

Acute mesenteric ischaemia is a life-threatening emergency.

Maintain a high index of suspicion for bowel ischaemia, because the signs and symptoms are relatively non-specific yet the condition has significant morbidity and mortality, particularly if diagnosis is delayed.[29] Time is of the essence to improve outcomes; early recognition, appropriate diagnostic studies, and aggressive treatment should be instigated emergently and expeditiously.

The classic presentation of acute mesenteric ischaemia is abdominal pain out of proportion to examination.

Use imaging to make a diagnosis in the absence of highly specific or definitive signs and symptoms. An urgent computed tomography scan is the first-line investigation of choice.

A history and physical examination alone are generally not sufficient to make the diagnosis.

Where clinically indicated, resuscitate in parallel with the diagnostic work-up in order to minimise the risk of ischaemia progressing. Administer supplemental oxygen and adequate fluid replacement, and correct acute heart failure or arrhythmias.

When fulminant ischaemic bowel disease is present, don’t allow extensive diagnostic testing to delay appropriate surgical intervention.

Be aware that bowel ischaemia encompasses a wide spectrum of disorders. Presenting features and history vary considerably. Alternative diagnoses must be excluded.[30]

Acute mesenteric ischaemia is a life-threatening emergency.

Maintain a high index of suspicion for bowel ischaemia, because the signs and symptoms tend to be non-specific yet the condition has significant morbidity and mortality, particularly if diagnosis is delayed.[29] Time is of the essence to improve outcomes; early recognition, appropriate diagnostic studies, and aggressive treatment should be instigated emergently and expeditiously.

Practical tip

A hallmark of salvageable acute intestinal ischaemia is very severe abdominal pain with a lack of physiological disturbance or physical signs.

Aim to differentiate mesenteric ischaemia from ischaemic colitis. Suggestive findings for each of the possible types of ischaemic bowel disease are as follows.

Acute mesenteric ischaemia

Most patients present with sudden abdominal pain, often peri-umbilical. The classic presentation is pain disproportionate to the physical examination findings.[8][20] It will generally persist and worsen. As ischaemia progresses to infarction, the pain may become more diffuse.[20] Nausea and vomiting may also be present.

The patient may be severely ill in a delayed presentation, where the bowel ischaemia is extensive or has progressed to infarction.

Patients with arterial embolus may describe sudden, severe abdominal pain with rapid, forceful bowel evacuation, possibly containing blood. Arterial embolus is the most common cause of acute mesenteric ischaemia.[31] Acute mesenteric ischaemia due to arterial embolus should be suspected in patients who describe sudden, severe abdominal pain with:[31]

Rapid, forceful bowel evacuation, possibly containing blood, and/or

High risk of thromboembolism.

Patients with mesenteric venous thrombosis have more variable presentations than patients with arterial aetiology.

Pain is often tolerated initially.

Typically, these patients describe colicky abdominal pain for a mean of 5 to 14 days before presentation; 25% of patients have had episodes of pain for >30 days before presentation.

About 60% to 70% of these patients have associated nausea and vomiting, and 30% have diarrhoea or constipation.[32]

A longer duration of symptoms before presentation in venous ischaemia may be associated with improved outcomes.[20]

Older patients with long-standing congestive heart failure, cardiac arrhythmias, recent myocardial infarction, hypotension, or peripheral vascular disease are at higher risk for acute mesenteric ischaemia than younger patients.

Younger patients may have a history of collagen vascular disease, vasculitis, hypercoagulable state, or vasoactive medication or cocaine use.

Consider intestinal ischaemia if the clinical picture does not suggest another abdominal pathology.[32]

Chronic mesenteric ischaemia

Insidious onset with repeated mild transient episodes over many months, becoming progressively more severe over time. Pain is poorly localised. It may worsen after exercise and often occurs after meals, gradually resolving over a few hours.[30]

Patients may avoid food or become fearful of eating (sitophobia).[30]

There may be significant weight loss, giving the patient a cachectic appearance.[30]

Patients may have associated nausea, and diarrhoea with or without blood.[30]

The ‘classic triad’ of chronic mesenteric ischaemia is postprandial pain, weight loss, and an abdominal bruit; however, this is found in only a minority (around 20%) of patients.[30]

Infarction of bowel is uncommon, as insidious onset allows some collateral circulation to develop.

Chronic mesenteric ischaemia usually occurs in older people. Women are affected more than men (ratio 3:1).

Patients frequently give a history of heavy smoking and other symptoms associated with atherosclerosis.

Coeliac compression syndrome is a type of chronic mesenteric ischaemia that occurs due to the median arcuate ligament compressing the coeliac axis.[31]

Consider this diagnosis particularly in younger patients (especially women) with unexplained abdominal pain and normal upper endoscopy as well as normal liver, pancreatic, and gastric laboratory studies, particularly in those patients who have an abdominal bruit (from partially obstructed flow in the coeliac axis).

Colonic ischaemia

Soon after the onset of ischaemia, there is usually pain with frequent bloody, loose stools, reflecting mucosal or submucosal damage. However, blood transfusion is rarely needed. Passage of maroon or red blood from the rectum is particularly characteristic of colonic ischaemia.

Patients typically describe mild to moderate pain that is usually felt peripherally, in contrast to the pain of acute mesenteric ischaemia, which is often described as peri-umbilical. The ischaemia is commonly in the ‘watershed’ areas of the colon (the areas of the colon between two major supplying arteries; see Pathophysiology), hence the pain is typically left-sided. Tenderness to palpation over the affected bowel occurs from early in the course of ischaemia, in contrast to acute mesenteric ischaemia, where tenderness is a relatively late sign.

Patients do not generally appear severely ill, unless fulminant ischaemia is present.

If colonic ischaemia progresses, pain becomes more continuous and diffuse. The abdomen becomes more distended and tender and there are no bowel sounds.

If ischaemia progresses further still and necrosis approaches, there is a significant leakage of fluid, electrolytes, and protein through the damaged mucosa, with shock and metabolic acidosis.

Important risk factors for colonic ischaemia are:[23]

Age >60 years

Around 90% of people with colonic ischaemia are over 60 years old

Haemodialysis

Hypertension

Hypoalbuminaemia

Diabetes mellitus

Constipation-inducing medications.

Colonic ischaemia is increasingly identified in younger people, associated with strenuous and prolonged physical exertion (e.g., long-distance running), various medications (e.g., oral contraceptives), cocaine use, and coagulopathies (e.g., protein C and S deficiencies, antithrombin III deficiency, activated protein C resistance).[4]

Colonic ischaemia may also occur:

Following aortic or cardiac bypass surgery

In association with vasculitides such as systemic lupus erythematosus or polyarteritis nodosa, infections (e.g., cytomegalovirus, Escherichia coli O157:H7), coagulopathies

After any major cardiovascular episode accompanied by hypotension

With obstructing or potentially obstructing lesions of the colon (e.g., carcinoma, diverticulitis).

Diagnosis is by colonoscopy or contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) imaging or flexible sigmoidoscopy/colonoscopy.[4] More than 80% resolve spontaneously or with conservative measures, but surgery may be required in acute, subacute, or chronic cases.

Predictors of poor outcomes include a lack of rectal bleeding and right-sided ischaemia.[33]

Non-occlusive ischaemia (mesenteric or colonic)

Typically seen in patients with underlying hypotension and volume deficits, usually inadequate cardiac output causing splanchnic hypoperfusion. This may be related to congestive heart failure, hypovolaemia, sepsis, and cardiac arrhythmias, haemodialysis, or even related to medications.[31][32]

Risk factors for non-occlusive ischaemia include older age, cardiac comorbidities, and medications such as digoxin and diuretics.[34][35] Diagnosis is by CT and CT angiography.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Comparison of symptoms/signs and investigations for the three types of ischaemic bowel diseaseDesigned by BMJ Knowledge Centre, with input from Dr Amir Bastawrous [Citation ends].

Take a thorough history to confidently exclude other potential diagnoses. Use a tool such as the SOCRATES mnemonic to explore the key characteristics of the abdominal pain:

Site

Onset

Character

Radiation

Associations – nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea

Timing, duration, frequency

Exacerbating and relieving factors

Severity.

Other important elements to elicit include smoking history, cardiovascular risk factors, comorbidities, and past medical history.

Assess vital signs as a priority to determine whether immediate resuscitation measures are required. Then perform a thorough examination of all systems, particularly focusing on the abdomen and cardiovascular system. When bowel ischaemia is associated with vasculitis or specific disease entities, characteristic dermatological, musculoskeletal, or further findings specific to the disease may be present.

Abdominal examination

Early in the course of acute mesenteric ischaemia the abdomen may initially be soft and non- or minimally tender to palpation. Typically, patients with acute mesenteric ischaemia initially report levels of abdominal pain greater than would be expected by the physical findings.

Patients with colonic ischaemia may have mild to moderate tenderness at an earlier stage in the course of ischaemia. This is felt more laterally over the affected parts of the colon compared with the pain and tenderness of acute mesenteric ischaemia, which is generally more peri-umbilical.

As ischaemia progresses towards infarction, patients develop signs of peritonitis, with a rigid, distended abdomen; guarding and rebound; percussion tenderness; and loss of bowel sounds.

It is imperative to consider and either diagnose or exclude acute mesenteric ischaemia in patients who present with severe abdominal pain and a paucity of significant abdominal findings. The dangers of a delay in diagnosis outweigh the risk of early invasive studies.[32]

Auscultation of the abdomen reveals an epigastric bruit (indicative of turbulent flow through an area of vascular narrowing) in 48% to 63% of patients.[19]

Rectal examination may demonstrate gross blood per rectum or microscopic blood upon testing for occult haemorrhage.

Peritonitis indicates a need for urgent surgical intervention.

Cardiovascular examination

Perform a cardiovascular examination, including an ECG. ECG may demonstrate arrhythmias that predispose to cardioembolic complications, such as atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter, or acute infarction that may be the aetiology of intestinal ischaemia.

Examination may reveal bruits on carotid auscultation, along with skin changes, absent hair, and absent distal pulses on the limbs, consistent with advanced atherosclerotic disease.

Laboratory tests

Initial blood work should include tests to direct initial resuscitation, help assess the severity of any ischaemia, and provide clues to alternative diagnoses.[36]

Full blood count

More than 90% of patients with acute mesenteric ischaemia will have an abnormally elevated leukocyte count.[8]

May reveal anaemia (often as a result of repeated episodes of melaena) that exacerbates ischaemia.

Urea and electrolytes[36]

Helps assess renal dysfunction and dehydration, frequently present in patients with ischaemic bowel disease.

Liver function tests[36]

May be elevated, as a consequence of septic shock or concomitant with bowel ischaemia.

Arterial blood gases and serum lactate

Coagulation studies, group and save, and crossmatch[36]

Aids in the diagnosis of any underlying coagulopathy as a risk factor for further thrombosis. Allows correction of any clotting dyscrasia as part of treatment.

Group and save in preparation for the possibility of transfusion.

Serum amylase

Elevated serum amylase is found in approximately half of patients with acute mesenteric ischaemia.[8]

D-dimer

May be elevated in intestinal ischaemia, but its use is limited because D-dimer is a very non-specific test.[8]

In suspected ischaemic colitis, also include:[36][37]

C-reactive protein

Faecal culture

Clostridium difficile toxin assay

Studies for ova, cysts, and parasites.

Prioritise an urgent computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen to diagnose ischaemia, and to exclude other potential diagnoses.[8][20][30]

If no alternative diagnosis is made following the CT scan, consider selective angiography in discussion with radiology. Based on the angiographic findings, treat the patient according to the specific cause of the ischaemia.

If you suspect chronic mesenteric ischaemia, discuss the imaging findings and the overall clinical picture with a multidisciplinary team (including at least a gastroenterologist, an interventional radiologist, and a vascular surgeon).[30]

If you suspect acute ischaemia and CT imaging or angiography is not immediately available, discuss the patient with a consultant surgeon, as prompt exploratory laparoscopy and possible laparotomy may be indicated in patients with suspected ischaemic bowel. Laparotomy without prior imaging may be indicated in unstable patients with peritoneal signs. Bear in mind, however, that CT imaging is widely available in developed countries such as the UK.

CT scanning

A CT scan is the first-line investigation of choice in the diagnosis of acute or chronic mesenteric ischaemia.[8][20][30][38] Obtain the scan early; prompt diagnosis (and intervention) is essential to improve the clinical outcome. Use multidetector CT scanning with intravenous contrast for suspected acute mesenteric ischaemia.[20] Consider a CT scan even in the presence of renal impairment in order to save life and prevent worsening renal injury.[8][9][20]

CT provides evidence for the extent of bowel compromise from ischaemia; it is useful for diagnosing acute mesenteric ischaemia, but findings can be non-specific in early ischaemia.[39][40] Early signs include bowel wall thickening and luminal dilation. Late signs include pneumatosis (gas in the bowel wall) and mesenteric or portal venous gas, which typically indicate necrotic bowel.[32][41] Other late signs include oedematous bowel, and variable enhancement of the bowel surrounded by free fluid.[31] May show thickening of the bowel wall with thumbprinting sign suggestive of submucosal oedema or haemorrhage, which suggests a worse prognosis.

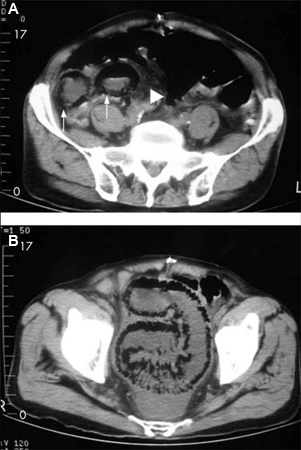

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan: colonic thickening with pneumatosis intestinalisFrom the collection of Dr Jennifer Holder-Murray; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: 84-year-old man presenting with symptoms suggestive of ischaemic bowel disease: (A) Abdominal CT revealing a massive circumferential and band-like air formation as intestinal pneumatosis (arrows) and pronounced oedema of mesenteric fat (arrowhead) around necrotic bowel loops; (B) Another slice of abdominal CT showing long segmental pneumatosis of the small bowelLin I, Chang W, Shih S, et al. Bedside echogram in ischaemic bowel. BMJ Case Reports 2009:bcr.2007.053462 [Citation ends].

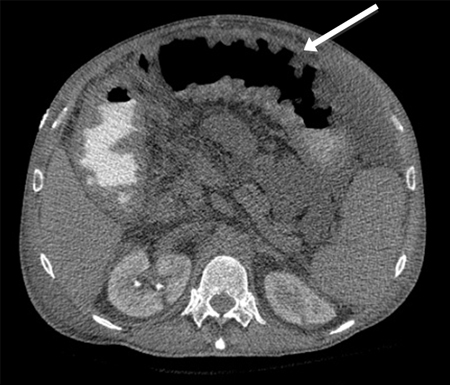

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: 84-year-old man presenting with symptoms suggestive of ischaemic bowel disease: (A) Abdominal CT revealing a massive circumferential and band-like air formation as intestinal pneumatosis (arrows) and pronounced oedema of mesenteric fat (arrowhead) around necrotic bowel loops; (B) Another slice of abdominal CT showing long segmental pneumatosis of the small bowelLin I, Chang W, Shih S, et al. Bedside echogram in ischaemic bowel. BMJ Case Reports 2009:bcr.2007.053462 [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan: circumferential wall thickening of the transverse colon; white arrow shows thumbprintingFrom the collection of Dr Amir Bastawrous; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan: circumferential wall thickening of the transverse colon; white arrow shows thumbprintingFrom the collection of Dr Amir Bastawrous; used with permission [Citation ends].

It also enables stratification of patients to differentiate those who would benefit from mesenteric angiography from those who require primary surgery; CT can also inform pathological staging; the degree of involvement of each layer of the gastrointestinal tract (mucosa, submucosa, muscularis, and serosa) can be used to estimate the probability of reversibility of the ischaemia, therefore helping to guide treatment.[42]

For diagnosing acute mesenteric vein thrombosis (MVT), contrast-enhanced CT is the procedure of choice, enabling diagnosis in >90% of patients. A central lucency in the mesenteric veins after injection of contrast is suggestive of a thrombosis. Other suggestive findings include enlargement of the superior mesenteric vein, thickening of the bowel wall, or dilated collaterals in a thickened mesentery. If MVT is diagnosed on CT scan, angiography may not be necessary, although it does provide better delineation of thrombosed veins and facility for intra-arterial vasodilators.[32]

Consider early CT angiography in a patient with abdominal pain and lactic acidosis.[8] CT angiography has replaced conventional angiography as standard practice for evaluation of the mesenteric vasculature and diagnosis of acute mesenteric ischaemia.[30] It can be used in the diagnosis of non-occlusive mesenteric ischaemia (NOMI).[43] CT angiography can also provide information to help decide on treatment modality, such as endovascular repair.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT angiogram: Acute superior mesenteric artery thrombusFrom the collection of Dr Jennifer Holder-Murray; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT angiography: 3-dimensional reconstruction with superior mesenteric artery stenosis from severe atherosclerotic plaque in a patient on follow-up imaging for endovascular aneurysm repairFrom the collection of Dr Jennifer Holder-Murray; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT angiography: 3-dimensional reconstruction with superior mesenteric artery stenosis from severe atherosclerotic plaque in a patient on follow-up imaging for endovascular aneurysm repairFrom the collection of Dr Jennifer Holder-Murray; used with permission [Citation ends].

In ischaemic colitis, features of colitis, such as bowel wall thickening and pericolic fat stranding, may be seen on CT.[36][44] Right-sided involvement seen on CT may indicate severe disease needing surgical intervention.[36][44]

Magnetic resonance angiography

Magnetic resonance angiography may have a role in diagnosing chronic mesenteric ischaemia.[30] However, CT angiography is a better examination than magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) for the diagnosis of chronic mesenteric ischaemia because of its capacity for higher resolution in combination with faster scans.

The time required to perform MRA examinations, and the possible need for bowel stimulation with a meal, limit the usefulness of MRA in the diagnosis of acute mesenteric ischaemia.

Mesenteric angiography

Historically, mesenteric angiography has been the definitive test for diagnosing mesenteric ischaemia. In current practice it is usually preceded by positive CT angiography in the acute setting. Sensitivity is 74% to 100%, and specificity is 100%.[32]

Mesenteric angiography can diagnose NOMI before infarction occurs; look for:

Narrowing of the origins of the superior mesenteric artery branches

Irregularities in these branches

Spasm of the mesenteric arcades

Impaired filling of the intramural vessels.

Mesenteric angiography is often performed with the intention of proceeding to intervention. It enables treatment by infusion of vasodilators or thrombolytic agents (which have been shown to improve outcomes).

For the diagnosis of chronic mesenteric ischaemia, angiography needs to demonstrate severe occlusion of at least 2 of the 3 splanchnic vessels, although in the absence of symptoms an abnormal angiography result alone is not sufficient for diagnosis.[45]

Sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy

Sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy can be used to establish the diagnosis of colonic ischaemia, establish severity, and exclude alternative causes of colonic inflammation. However, if urgent surgical intervention is required due to the condition of the patient, surgery should not be delayed to carry out sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy.

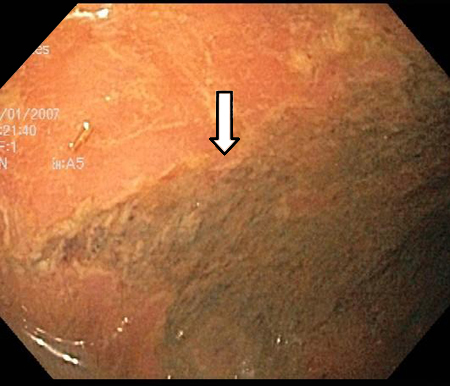

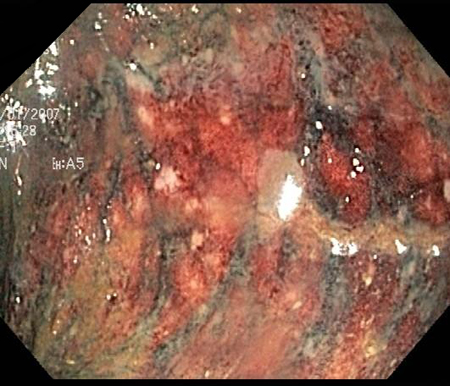

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Colonoscopy: demarcation between ischaemic and normal colonFrom the collection of Dr Jennifer Holder-Murray; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Colonoscopy: denudation of colonic mucosaFrom the collection of Dr Jennifer Holder-Murray; used with permission [Citation ends].

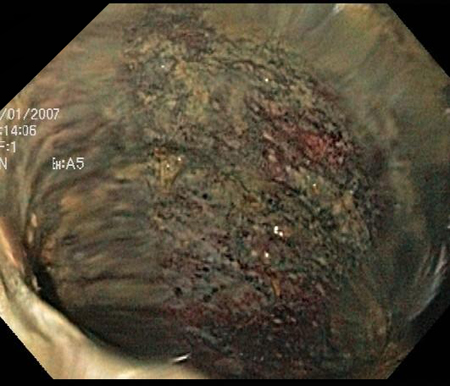

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Colonoscopy: denudation of colonic mucosaFrom the collection of Dr Jennifer Holder-Murray; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Colonoscopy: mucosal sloughing and likely to be non-viable colonFrom the collection of Dr Jennifer Holder-Murray; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Colonoscopy: mucosal sloughing and likely to be non-viable colonFrom the collection of Dr Jennifer Holder-Murray; used with permission [Citation ends].

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy

Perform upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in patients with suspected chronic mesenteric ischaemia, in order to rule out alternative diagnoses involving the upper gastrointestinal tract.[30]

Mesenteric duplex ultrasound

Mesenteric duplex ultrasound is particularly useful if obstruction is proximal in the mesenteric vessels but ultrasound cannot assess distal mesenteric blood vessel flow and non-occlusive aetiology of ischaemia.[9] This is mostly used in vascular units where it is the first-line investigation of choice for the assessment of chronic mesenteric ischaemia.[46]

Ultrasound of the bowel can be used to diagnose ischaemic colitis (providing the user has adequate expertise) and differentiate between left- and right-sided disease.[37] It is an alternative for patients unable to tolerate contrast media.[36] However, it is not considered a routine investigation and should only be performed by a radiologist with sufficient ultrasound expertise.

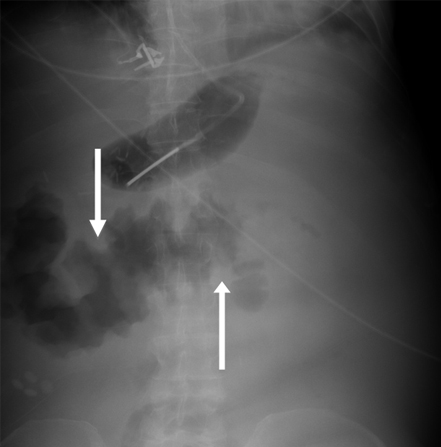

Abdominal x-ray

Abdominal x-ray has a limited role in the diagnosis and evaluation of acute mesenteric ischaemia.[8][20] A negative radiograph does not exclude the diagnosis.[8] Plain x-rays are often normal early in the course of ischaemia or when ischaemia is mild. X-rays are not a frequently used investigation for ischaemic bowel disease.

With worsening ischaemia, plain x-rays may show formless loops of bowel, ileus, or thickening of the bowel wall with thumbprinting sign suggestive of submucosal oedema or haemorrhage.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Plain abdominal x-ray: shows marked wall thickening of the transverse colon compatible with the finding of thumbprinting (white arrows)From the collection of Dr Amir Bastawrous; used with permission [Citation ends].

Erect chest x-ray

Chest X-ray may show sub-diaphragmatic air, indicative of perforation of the bowel requiring prompt surgical intervention. X-rays are not a frequently used investigation for ischaemic bowel disease.

How to record an ECG. Demonstrates placement of chest and limb electrodes.

How to take a venous blood sample from the antecubital fossa using a vacuum needle.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer