Aetiology

Arterial compromise

Embolism

Embolic arterial obstruction accounts for 40% to 50% of acute mesenteric ischaemia; most commonly affecting the superior mesenteric artery.[14] The embolus usually originates from a left-sided heart thrombus, or from spontaneous or iatrogenic rupture and embolisation from an aortic atherosclerotic plaque or aneurysm.[15][16][17] Interventional radiological procedures are the most common cause of iatrogenic plaque rupture.

Thrombosis

About 15% to 20% of acute mesenteric ischaemia results from thrombus occurring as a progression of atherosclerosis at the origin of the superior mesenteric artery.[15][18] Mesenteric atherosclerotic plaques may rupture with associated acute thrombosis of the vessel. Subacute or chronic ischaemia may result from partial occlusion of the vessel.

Vasculitis

Rheumatoid arthritis, polyarteritis nodosa, systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, Takayasu arteritis, and thrombo-angiitis obliterans can all result in ischaemia of the bowel. The exact clinical picture varies depending upon factors such as the size of the mesenteric vessel involved.

External compression

Rarely, extrinsic compression of the coeliac axis can lead to mesenteric ischaemia, usually due to the median arcuate ligament of the diaphragm and surrounding nerve plexus impinging onto the coeliac axis. It occurs more often in women than in men.[19]

Tumours and other masses within the abdomen can also surround and ultimately compress blood vessels supplying the bowel, causing ischaemic damage.

Venous compromise

Venous thrombosis

Accounts for 5% to 15% of cases of acute mesenteric ischaemia.[1][14] Frequently involves the superior mesenteric vein.

Usually associated with cirrhosis or portal hypertension; other potential associations include inheritable hypercoagulable states (e.g., factor V Leiden, protein C deficiency, prothrombin G20210A mutation), pancreatitis, malignancy, oral contraceptive use, and recent surgery. Approximately half of patients presenting with venous thrombosis have had a prior history of deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolus.[14][19]

Hypoperfusion (i.e., non-occlusive ischaemia)

Accounts for as much as 20% of cases of acute mesenteric ischaemia.[20]

Shock, or hypotension, or relative mesenteric hypotension (from any aetiology). Prominent causes include:

Heart failure

Dialysis

Drug-related

Such as digoxin, oestrogen, contraceptives, vasopressin, vasopressors, danazol, flutamide, glycerin enema, alosetron, immunosuppressives, psychotropics, imipramine, adrenaline (epinephrine), sumatriptan, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, ergot, diconal, laxatives, pegylated interferon, methamphetamines, and cocaine.[21][22]

Recent surgery or trauma

Such as aortic aneurysm repair, aorto-iliac bypass, colectomy, colonoscopy.

Increased risk with enteral nutrition in post-surgical or trauma patients in intensive care (incidence reported between 0.3% and 8.5%).[20]

Infection

Such as cytomegalovirus, hepatitis B, Escherichia coli O157:H7.

Other

Such as pancreatitis, polycythaemia vera, phaeochromocytoma, carcinoid syndrome.

Pathophysiology

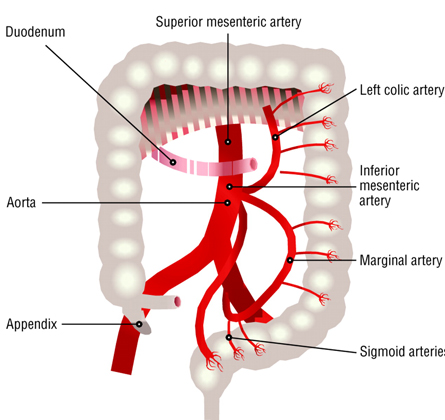

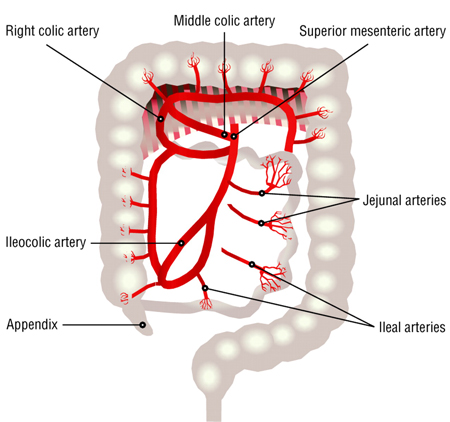

The small intestine receives blood via the coeliac artery and the superior mesenteric artery (SMA). The colon receives blood via the SMA and the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA). The rectum also receives blood via branches of the internal iliac artery. Several collateral arteries exist between the SMA and the IMA, including the marginal artery of Drummond and the arc of Riolan. The splenic flexure and the recto-sigmoid junction are two watershed areas where collateralisation of blood flow may be limited.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Distribution of blood flow to the colon originating from the inferior mesenteric artery, branches of which include the left colic, marginal, and sigmoid arteries and supply the left colon and superior portion of the rectumBMJ 2003; 326 doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7403.1372 [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Distribution of blood supply to the small intestine and colon from the superior mesenteric artery, branches of which include the middle, right, and ileocolic arteries as well as jejunal and ileal arteries and arteriolesBMJ 2003; 326 doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7403.1372 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Distribution of blood supply to the small intestine and colon from the superior mesenteric artery, branches of which include the middle, right, and ileocolic arteries as well as jejunal and ileal arteries and arteriolesBMJ 2003; 326 doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7403.1372 [Citation ends].

Ischaemia occurs secondary to hypoperfusion of an intestinal segment. When hypoperfusion is insidious in onset, collateral blood flow may develop, precluding or minimising ischaemia; however, the regions of the intestine with a solitary arterial supply, and the watershed areas, are both at increased risk of developing ischaemia. The degree of intestinal injury is dependent on the duration and severity of ischaemia. Acute or subacute mucosal sloughing and ulcerations occur as a result of ischaemia. The loss of the mucosal barrier allows for bacterial translocation and toxin or cytokine absorption. Reperfusion injury can also occur if blood supply is re-established after a prolonged interruption. Segments of ischaemic bowel that do not suffer acute necrosis or perforation can heal with stenosis or stricture as the long-term sequelae of bowel ischaemia.

Thromboembolic events that lead to mesenteric ischaemia usually involve the SMA instead of the other mesenteric arteries (IMA and coeliac artery). This is because of the anatomical position of the SMA; the SMA is positioned vertically in relation to the aorta while the other vessels form more oblique angles with the aorta.

Classification

Intestinal ischaemia can be classified into three broadly defined types:[1]

Acute mesenteric ischaemia

Superior mesenteric artery embolus

Superior mesenteric artery thrombosis

Non-occlusive mesenteric ischaemia

Superior mesenteric vein thrombosis

Focal segmental ischaemia.

Chronic mesenteric ischaemia

Colonic ischaemia

Reversible ischaemic colonopathy

Transient ulcerating ischaemic colitis

Chronic ulcerating ischaemic colitis

Colonic stricture

Colonic gangrene

Fulminant universal ischaemic colitis.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer