Recommendations

Key Recommendations

If you suspect IE, evaluate the patient urgently and seek early input from a cardiologist and an infectious disease or microbiology specialist.

IE can be rapidly fatal if untreated. Therefore, early detection and prompt management are critically important.

Always suspect IE in a patient with a fever and symptoms/signs of embolism. Also suspect IE in a patient with fever alongside heart failure or risk factors for IE. However, be aware that clinical presentation of IE is highly variable according to the causative micro-organism; the presence or absence of pre-existing cardiac disease, prosthetic valves, or cardiac devices; and whether the presentation is acute or subacute.[7]

About 80% of patients present with fever, which is often associated with systemic symptoms including chills, poor appetite, and weight loss.[7]

Heart murmurs are found in up to 65% of patients but the classic new or worsening cardiac murmur is rare.[7]

Up to 25% of patients with IE have evidence of embolic phenomena at presentation.[7]

Always consider IE if the patient has Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia.[7] IE is highly prevalent in these patients and S aureus can cause devastating effects once infection is established.[7]

Think ' Could this be sepsis?' based on acute deterioration in a patient with suspected infective endocarditis.[22][23][24] See Sepsis in adults.

Use a systematic approach, alongside your clinical judgement, for assessment; urgently consult a senior clinical decision-maker (e.g., ST4 level doctor in the UK) if you suspect sepsis.[22][24][25][26]

Refer to local guidelines for the recommended approach at your institution for assessment and management of the patient with suspected sepsis.

Prioritise ordering the key initial investigations: three sets of of blood cultures taken at 30-minute intervals and echocardiography.[7]

However, do not delay empirical antibiotic therapy while waiting to take three sets of blood cultures if the patient is unwell (e.g., with sepsis).[27]

When taking blood cultures, obtain a 10 mL blood sample for each aerobic and anaerobic bottle.[28]

Once blood culture and echocardiography results are confirmed, use the European Society of Cardiology diagnostic criteria to classify the diagnosis of IE as 'definite', 'possible', or 'rejected'.[7] Further investigations may be required if there is ongoing high clinical suspicion of IE, even if the diagnosis is classified as 'possible' or 'rejected' according to the criteria.[7] See Criteria.

Always suspect IE in a patient with a fever and symptoms/signs of embolism.[7] Also suspect IE in a patient with fever alongside heart failure or risk factors for IE. IE is a diagnostic challenge owing to its highly variable clinical presentation. Contributing factors include the causative micro-organism; the presence or absence of pre-existing cardiac disease, prosthetic valves, or cardiac devices; and whether the presentation is acute or subacute.

Fever is the most consistent feature; seen in 80% of patients; often associated with systemic symptoms including chills, poor appetite, and weight loss.[7] Fever may be low-grade in subacute IE.[7]

Heart murmurs are found in up to 65% of patients with IE but the classic new or worsening cardiac murmur is rare.[7]

Older or immunocompromised patients may present atypically; fever is less common than in younger patients.[7] As the population ages, IE is becoming more frequently seen in these groups, with trends towards worsening outcomes.[29] Diagnosis in older people is often made later in the course of the disease as a result of more indolent presentations, which likely contributes to poorer outcomes.

Patients with acute IE typically develop symptoms over a period of days and for up to 6 weeks. They may present with spiking fevers, tachycardia, fatigue, and progressive damage to cardiac structures. However, patients with subacute IE usually develop symptoms over the course of 6 weeks to months, and will often describe vague constitutional symptoms.

Always consider IE if the patient has Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia.[7] IE is highly prevalent in these patients and S aureus can cause devastating effects once infection is established.[7]

If you suspect IE, evaluate the patient urgently and seek early input from a cardiologist and infectious disease or microbiology specialist.[7]

Think ' Could this be sepsis?' based on acute deterioration in a patient with suspected infective endocarditis.[22][23][24] See Sepsis in adults.

Use a systematic approach, alongside your clinical judgement, for assessment; urgently consult a senior clinical decision-maker (e.g., ST4 level doctor in the UK).[22][24][25][26]

Refer to local guidelines for the recommended approach at your institution for assessment and management of the patient with suspected sepsis.

There are multiple challenges to diagnosing IE in the intensive care unit, including an often atypical presentation that may be concealed by other pathology.

Make an assessment of risk factors for IE. These include:[30]

Acquired valvular heart disease with stenosis or regurgitation

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

Previous infective endocarditis

Structural congenital heart disease, including surgically corrected or palliated structural conditions, but excluding isolated atrial septal defect, fully repaired ventricular septal defect, fully repaired patent ductus arteriosus, and closure devices that are judged to be endothelialised

Valve replacement or implantation of a cardiac device (e.g., pacemaker, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator)[31]

Use of intravenous drugs[7]

Recent vascular access (e.g., peripheral venous cannula, central venous catheter).[32]

In addition, ask the patient about symptoms of IE, including:[7]

Features of heart failure (see Acute heart failure):

Dyspnoea on exertion

Orthopnoea

Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea

Features of emboli:

Symptoms of stroke (see Ischaemic stroke)

Symptoms of splenic embolism

Symptoms of pulmonary embolism

Non-specific constitutional symptoms (a feature of subacute IE):

Night sweats

Malaise

Fatigue

Anorexia

Weight loss

Myalgias.

Include in your assessment a cardiac, abdominal, and neurological examination to check for:

A heart murmur[7]

Heart murmurs are found in up to 65% of patients but the classic new or worsening cardiac murmur is rare

Splenomegaly[33]

Signs of stroke (see Ischaemic stroke)[7]

Meningism.[7]

Practical tip

Be aware that cardiac murmurs in right-sided IE (which is more prevalent in patients who use intravenous drugs) are soft in nature and can therefore be easily missed in the accident and emergency department.

Look for classic signs of IE (although these are uncommon), which include:

Janeway lesions (haemorrhagic, macular, painless plaques with a predilection for the palms and soles)

Osler nodes (small, painful, nodular lesions usually found on the pads of the fingers or toes)

Splinter haemorrhages (commonly noted in the nails of the upper and lower extremities)

Cutaneous infarcts.

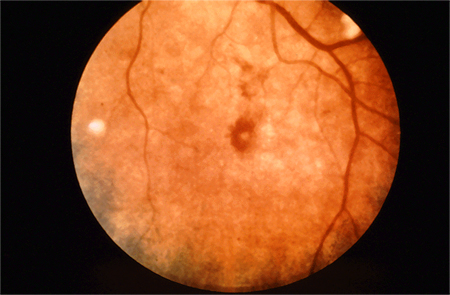

Other features include palatal petechiae, Roth spots (oval, pale, retinal lesions surrounded by haemorrhage seen on fundoscopy), and glomerulonephritis.[7]

Always perform fundoscopy, particularly if you suspect fungal IE.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Janeway lesionsFrom the collection of Sanjay Sharma, St George’s University of London, UK; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Osler nodeFrom the collection of Sanjay Sharma, St George’s University of London, UK; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Osler nodeFrom the collection of Sanjay Sharma, St George’s University of London, UK; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cutaneous infarctsFrom the collection of Sanjay Sharma, St George’s University of London, UK; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cutaneous infarctsFrom the collection of Sanjay Sharma, St George’s University of London, UK; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Roth spotsFrom the collection of Sanjay Sharma, St George’s University of London, UK; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Roth spotsFrom the collection of Sanjay Sharma, St George’s University of London, UK; used with permission [Citation ends].

Practical tip

Classic immunological features (e.g., Osler nodes, Roth spots) are uncommon in acute IE due to rapid onset of disease process.

More info: Classic signs of IE

Although classic signs may still be seen in many parts of the world in subacute forms of IE, they are increasingly rare in the developed world because patients tend to present at an earlier stage in the disease process. Vascular and immunological signs such as splinter haemorrhages, Roth spots, and glomerulonephritis remain common, regardless of geographical location.[7]

Laboratory tests

Obtain three sets of blood cultures from different venepuncture sites taken at 30-minute intervals prior to the initiation of antibiotic therapy.[7] Blood cultures are the most important laboratory test for confirming IE.

If the patient is unwell (e.g., with sepsis), do not delay empirical antibiotic therapy while waiting to take three sets of blood cultures.[27] The volume of blood sent for culture is more important than the number of sets of cultures.[34]

Use peripheral venepuncture sites and a meticulous sterile technique to minimise risk of contamination and a misleading result.[7] Take a 10 mL blood sample for each aerobic and anaerobic bottle.[28]

In practice, if the patient has a central venous catheter (CVC), take blood cultures from the CVC in addition to peripheral venepuncture sites because IE may be caused by infection of the CVC. Consider removing the CVC if the patient is bacteraemic.

When a micro-organism has been identified, repeat the blood cultures after 48 to 72 hours to check the effectiveness of treatment.[7]

Seek advice from an infectious disease or microbiology specialist if the blood cultures are negative after 48 hours but there is ongoing clinical suspicion of IE.[7] Blood culture-negative IE (no causative micro-organism grown using standard blood culture methods) requires more specialist investigation (e.g., systematic serological testing and blood polymerase chain reaction).[7]

Order blood tests including a full blood count and C-reactive protein (CRP), and obtain a urine sample for urinalysis.[7]

If the patient is febrile, laboratory signs of infection (such as elevated CRP or leukocytosis), anaemia, and microscopic haematuria support a diagnosis of IE. However, these are not specific for the diagnosis of IE.

In practice, CRP is also useful as a baseline test and to monitor response to treatment.

Consider ordering erythrocyte sedimentation rate (as a marker of infection) and complement levels (if you suspect autoimmune IE), although these are rarely used in practice.

Use urinalysis to evaluate renal involvement. In addition, order urea and electrolytes, glucose, and liver function tests to mark progress of the disease, and to assess vital organ function and systemic effects of infection.

Check your local protocols for guidance on the most appropriate immunological blood tests to use. The European Society of Cardiology recommends considering rheumatoid factor (which forms part of the Duke criteria – see Criteria) and antinuclear antibodies.[7] Some centres (e.g., in the UK) may use anti-cyclic citrullinated peptides (anti-CCP) instead of rheumatoid factor.

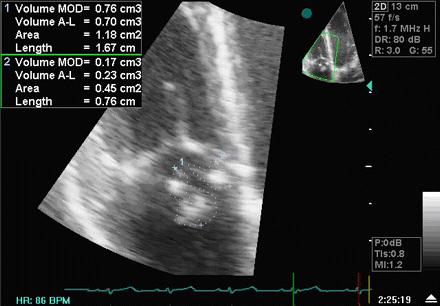

Echocardiography

Order echocardiography if you suspect IE.[7][35] Echocardiography is important not only for confirming or ruling out the diagnosis but also for evaluation of complications and prognosis. The choice between transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) and trans-oesophageal echocardiography (TOE) is often difficult and continues to be the subject of debate.[7][35][36][37] The European Society of Cardiology recommends that:[7]

Any patient suspected of having native valve IE should be screened with TTE

TOE is the preferred form of echocardiography if the patient has a prosthetic valve or intracardiac device with suspected IE.[35] TOE is also indicated, in addition to TTE, if:

TTE is positive, unless the patient has isolated right-sided native valve IE with good-quality TTE examination and unequivocal echocardiographic findings

TTE is negative or non-diagnostic but there is high clinical suspicion of IE[35]

If the patient has Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia, base the decision to use TTE or TOE on individual patient risk factors and the mode of acquisition of S aureus bacteraemia.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Image from transoesophageal echocardiogram. White arrow indicates vegetation on the patient's aortic valveTeoh LS, Hart HH, Soh MC, et al. Bartonella henselae aortic valve endocarditis mimicking systemic vasculitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2010 Oct 21;2010. pii: bcr0420102945 [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A transthoracic echo showing large mobile vegetations on the anterior and posterior leaflets of the tricuspid valveFoley JA, Augustine D, Bond R, et al. Lost without Occam's razor: Escherichia coli tricuspid valve endocarditis in a non-intravenous drug user. BMJ Case Rep. 2010 Aug 10;2010. pii: bcr0220102769 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A transthoracic echo showing large mobile vegetations on the anterior and posterior leaflets of the tricuspid valveFoley JA, Augustine D, Bond R, et al. Lost without Occam's razor: Escherichia coli tricuspid valve endocarditis in a non-intravenous drug user. BMJ Case Rep. 2010 Aug 10;2010. pii: bcr0220102769 [Citation ends].

Repeat TTE and/or TOE within 5 to 7 days (or earlier if S aureus bacteraemia is present) for any patient with negative initial echocardiography but where clinical suspicion of IE remains high.[7]

ECG

Record an ECG; progression of the infection may lead to conduction abnormalities.[38]

Conduction abnormalities secondary to IE (mainly first-, second-, and third-degree atrioventricular block) are uncommon but are associated with worse prognosis and higher mortality compared with patients without conduction abnormalities.[39]

Blood culture and echocardiography results are used to confirm or reject a diagnosis of IE, with most clinicians accepting the presence of IE if there is clinical suspicion with positive blood cultures and endocardial involvement on echocardiography. The most widely used criteria now are the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) diagnostic criteria, which were updated in 2023 and incorporate a multimodality imaging approach in addition to the existing Duke criteria for diagnosis.[7] See also Criteria.

According to the ESC 2023 algorithm for the diagnosis of IE, if the diagnosis of IE is classified as ‘possible’ or ‘rejected’ but there is still a high level of clinical suspicion:[7]

Repeat blood cultures

Repeat echocardiography within 5-7 days

Perform cardiac CT angiography (CTA) to diagnose valvular lesions

Consider other imaging modalities:

Brain or whole-body imaging (MRI, CT, PET/CT, or WBC SPECT) to detect distant lesions in suspected native valve IE

WBC SPECT and brain or whole-body imaging (MRI, CT, PET/CT, or WBC SPECT) to detect distant lesions in suspected prosthetic valve IE

PET/CT to detect pocket infection or pulmonary embolism in patients with cardiac device-related IE.

If the diagnosis of IE is confirmed ‘definite’, further imaging is still warranted:

Cardiac CTA if there are suspected paravalvular complications and trans-oesophageal echocardiography (TOE) is inconclusive

Brain and whole-body imaging (CT, 18F-FDG-PET/CTA, and/or MRI) for all patients with confirmed IE, in particular if there are symptoms suggestive of extracardiac complications.

See Further imaging below.

Computed tomography (CT)

CT imaging is used for the diagnosis of native and prosthetic valve IE and for detection of complications of IE, including abscesses, pseudoaneurysms, and fistulae. Cardiac CT has been found to compare favourably with transthoracic echocardiography in detecting valvular abnormalities in patients with IE, but it may miss small defects (e.g., small leaflet perforations [≤2 mm diameter], small vegetations <10 mm).[7][40] Cardiac CT is also used to assess the coronary arteries prior to cardiac surgery.[7]

Whole-body and brain CT can be used to look for distant lesions, systemic complications of IE, and septic emboli, as well as having a role in detecting extracardiac sources of bacteraemia and potentially alternate diagnoses in patients where IE has been excluded.[7] CT angiography is a sensitive and specific test for detecting mycotic arterial aneurysms; MRI is superior for assessment of neurological complications in terms of imaging, but is limited by accessibility and availability.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

MRI is of less diagnostic value than CT, but is the imaging modality of choice when investigating the cerebral complications of IE, with studies consistently reporting cerebral infarcts in up to 80% of patients.[7][41] MRI also reveals cerebral lesions in 50% of patients who do not demonstrate neurological symptoms.[42] MRI is also used to assess spinal involvement in IE, including spondylodiscitis and vertebral osteomyelitis.[7]

Nuclear imaging and photon emission tomography (PET)

18F-FDG-PET/CT and white blood cell (WBC) single-photon emission CT (SPECT) are used in cases of suspected prosthetic valve IE where echocardiography is not diagnostic.[7]

Whole-body imaging with 18F-FDG-PET/CT can be useful to detect distant lesions, mycotic aneurysms, and portal of entry of bacteria, and to monitor response to antibiotic treatment in patients for whom surgery is being considered.[7]

How to record an ECG. Demonstrates placement of chest and limb electrodes.

How to take a venous blood sample from the antecubital fossa using a vacuum needle.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer