Aetiology

The most common cause of a skull fracture is a fall from a height (28% to 35%). Other causes include a road traffic accident (20% to 25%) and an assault resulting in head trauma in adults (30%).[2][4][5][8][11] However, there is some variability according to age; the most common causes in infants are falls and abuse; in older children, falls and road traffic accidents; in adults, falls, followed by road traffic accidents, followed by assaults.[2][4][7][10][11] Linear fractures are usually the result of minor to moderate force over a large surface and hence are common after falls. Comminuted fractures and depressed fractures result from more significant force over a smaller surface area and are more common following assaults with blunt or sharp objects, or with penetrating trauma, especially gunshot wounds.

Skull fractures most often affect young, active people, and the vast majority of patients are male, who, in general, are at higher risk of traumatic injury, possibly because of high-risk behaviours and more common involvement in crime and violent activities.[3]

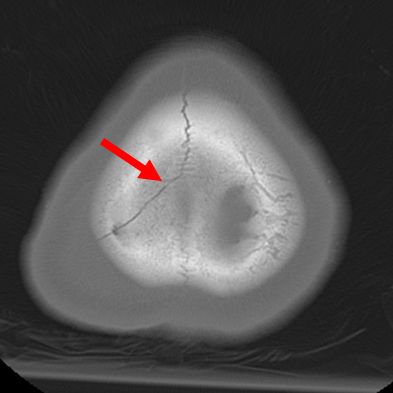

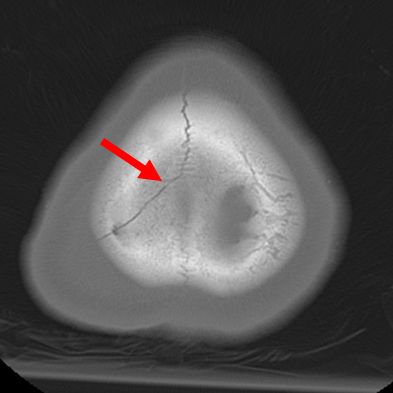

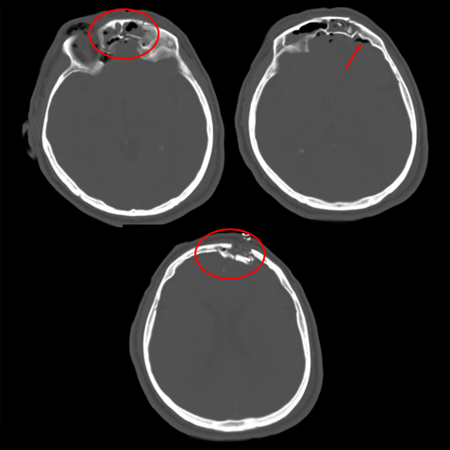

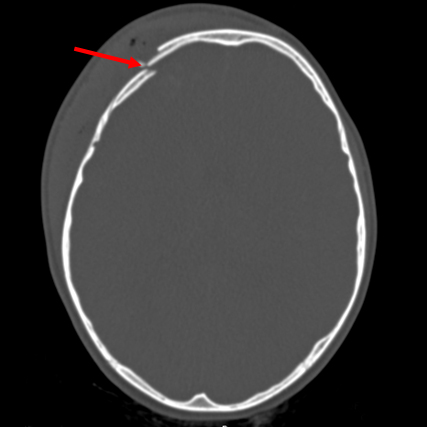

Skull fracture may be a presenting sign of child abuse, and this should be suspected if the social circumstances of injury are uncertain or of a suspicious nature. However, skull fractures are more prevalent in non-abuse, than abuse, in children younger than 2 years old. The most common type of fracture in both situations is a linear parietal fracture. Other signs of abuse that may be present include retinal haemorrhages, coexisting apnoea or another form of acute respiratory compromise, coexisting bruising to the head, neck or torso, or rib or long-bone fractures.[12][13][14] See Child abuse.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Linear parietal fracture without depression [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Comminuted non-depressed fracture [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Comminuted non-depressed fracture [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Depressed skull fracture: level of depression equal to thickness of cortex [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Depressed skull fracture: level of depression equal to thickness of cortex [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Transcranial gunshot wound [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Transcranial gunshot wound [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Gunshot wound with comminuted elevated fracture and pneumocephalus [Citation ends].

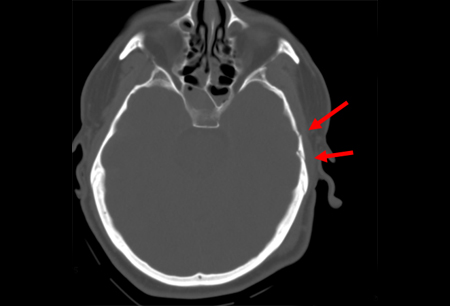

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Gunshot wound with comminuted elevated fracture and pneumocephalus [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Gunshot wound with perpendicular blowout fracture [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Gunshot wound with perpendicular blowout fracture [Citation ends].

Pathophysiology

Blunt force trauma results in direct transfer of energy to the skull, which can fracture in response to the force. Specifically vulnerable anatomical sites include the thin squamous temporal and parietal bone over the temples, and the sphenoid wings. Gunshots can cause fractures directly by punching out lesions in their path, or can fracture the skull in response to pressure release from the shockwave of high-velocity bullets. The latter are generally stellate in nature and perpendicular to the path of the bullet at the point of maximal energy dispersal within the brain parenchyma. Larger, slower missiles can cause wedge-shaped fractures that often cantilever, resulting in depression of the fracture fragments if the trajectory with the skull is tangential.[15]

Classification

Types of skull fracture

Skull fractures may be secondary to a blunt force (assault, fall) or penetrating trauma (gunshot, explosive device).

They may be simple linear fractures or more complicated comminuted fractures.

The fracture may be closed or open (with communication to the overlying skin or mucous membranes; e.g., frontal sinus).

The fracture may be depressed if one bone fragment or edge is depressed below the other.

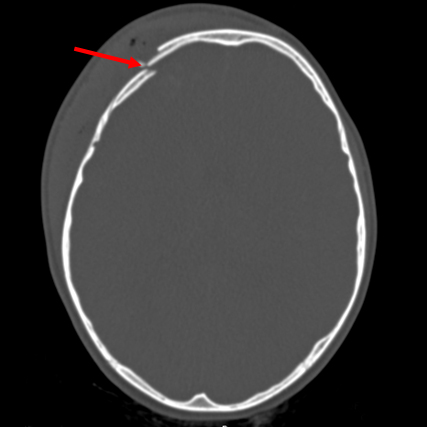

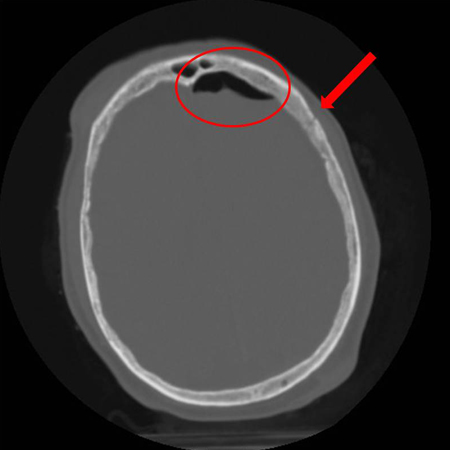

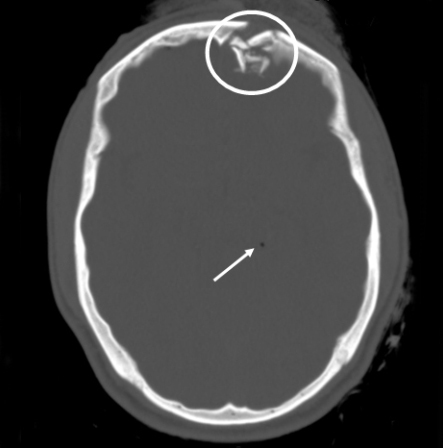

Fractures are also categorised according to location in the parietal and frontal portions of the cranium or in the temporal or occipital areas of the skull base. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Linear parietal fracture without depression [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Axial CT scan demonstrating an open non-depressed linear skull fracture (arrow) associated with pneumocephalus (circle) [Citation ends].

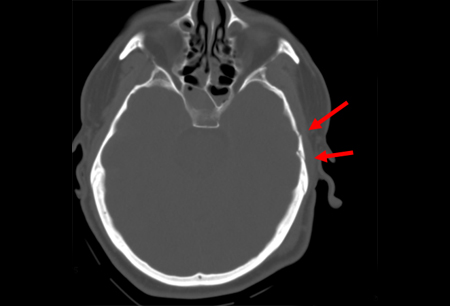

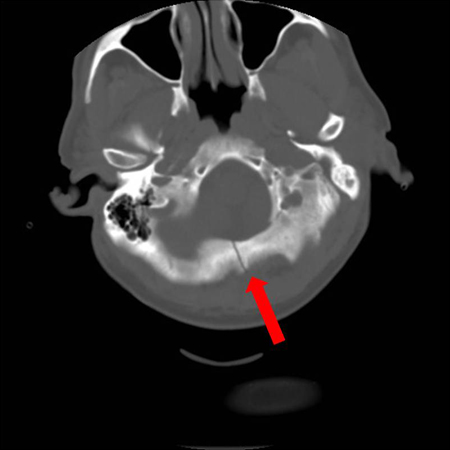

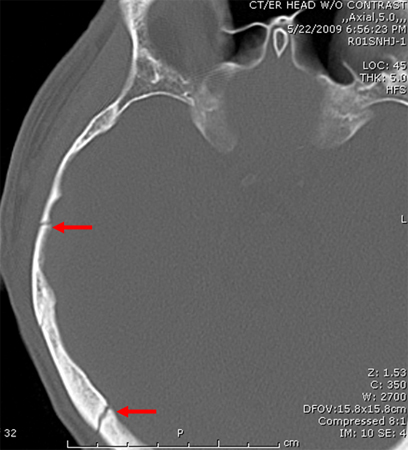

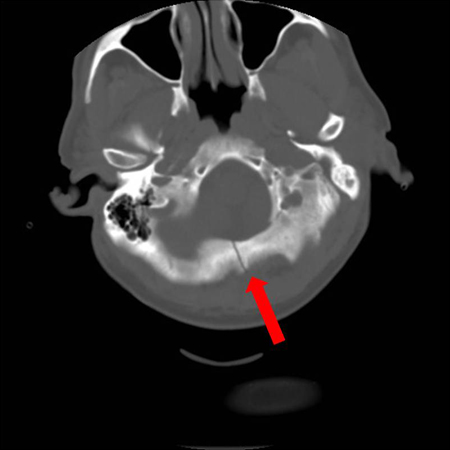

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Axial CT scan demonstrating an open non-depressed linear skull fracture (arrow) associated with pneumocephalus (circle) [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Axial CT scan showing non-depressed linear skull fracture (arrow) of the skull base involving the foramen magnum. This injury pattern is concerning for associated spinal fracture, cord injury, and blunt cerebrovascular injury [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Axial CT scan showing non-depressed linear skull fracture (arrow) of the skull base involving the foramen magnum. This injury pattern is concerning for associated spinal fracture, cord injury, and blunt cerebrovascular injury [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Comminuted non-depressed fracture [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Comminuted non-depressed fracture [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Comminuted depressed skull fracture with pneumocephalus [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Comminuted depressed skull fracture with pneumocephalus [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Comminuted depressed fracture of the frontal sinus with air, fluid, and bone fragments in frontal sinus and pneumocephalus; level of depression greater than width of cortex [Citation ends].

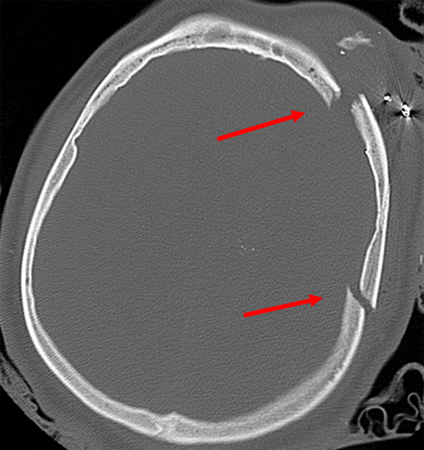

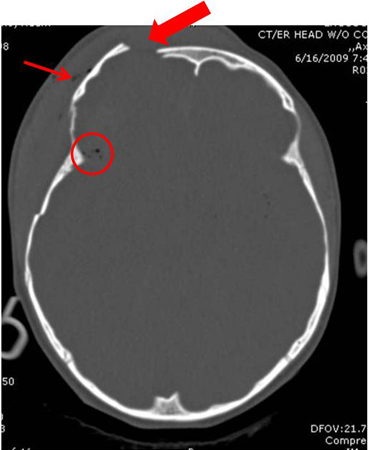

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Comminuted depressed fracture of the frontal sinus with air, fluid, and bone fragments in frontal sinus and pneumocephalus; level of depression greater than width of cortex [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Axial CT scan demonstrating open elevated linear skull fracture (large arrow). Note the air in the soft tissues (small arrow), the small amount of pneumocephalus associated with the fracture (circle), and that the level of elevation of the bone fragment is significantly more than the thickness of the bony tableFrom the teaching collection of Demetrios Demetriades; used with permission [Citation ends].

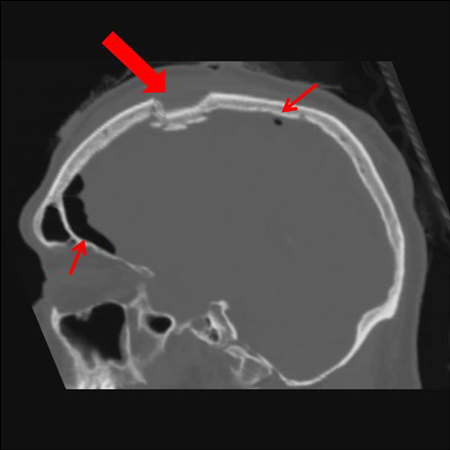

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Axial CT scan demonstrating open elevated linear skull fracture (large arrow). Note the air in the soft tissues (small arrow), the small amount of pneumocephalus associated with the fracture (circle), and that the level of elevation of the bone fragment is significantly more than the thickness of the bony tableFrom the teaching collection of Demetrios Demetriades; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Sagittal CT images of an open, comminuted, depressed skull fracture. Note the associated pneumocephalus (small arrows). The level of depression is greater than the bony table and there are a number of bone fragments impacted below the inner cortex of the opposing bone (large arrow). Despite lack of underlying associated brain injury, this fracture required operative debridement and elevation of the bone fragments. See also the corresponding coronal CT image [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Sagittal CT images of an open, comminuted, depressed skull fracture. Note the associated pneumocephalus (small arrows). The level of depression is greater than the bony table and there are a number of bone fragments impacted below the inner cortex of the opposing bone (large arrow). Despite lack of underlying associated brain injury, this fracture required operative debridement and elevation of the bone fragments. See also the corresponding coronal CT image [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Coronal CT of an open, comminuted, depressed skull fracture. The level of depression is greater than the bony table and there are a number of bone fragments impacted below the inner cortex of the opposing bone (large arrow). Despite lack of underlying associated brain injury this fracture required operative debridement and elevation of the bone fragments. See also the corresponding sagittal CT image [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Coronal CT of an open, comminuted, depressed skull fracture. The level of depression is greater than the bony table and there are a number of bone fragments impacted below the inner cortex of the opposing bone (large arrow). Despite lack of underlying associated brain injury this fracture required operative debridement and elevation of the bone fragments. See also the corresponding sagittal CT image [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Depressed skull fracture: level of depression equal to thickness of cortex [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Depressed skull fracture: level of depression equal to thickness of cortex [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Fracture of temporal bone [Citation ends].

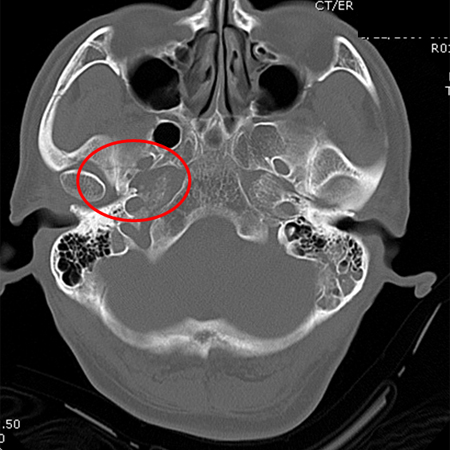

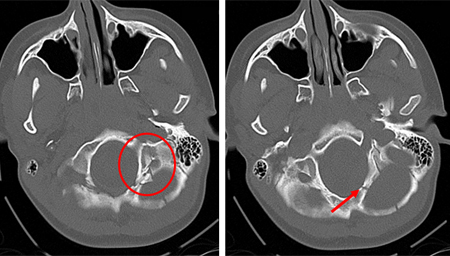

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Fracture of temporal bone [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Fracture of temporal bone extending into foramen ovale [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Fracture of temporal bone extending into foramen ovale [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Occipital fracture extending to foramen magnum: risk of brainstem compression by haematoma [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Occipital fracture extending to foramen magnum: risk of brainstem compression by haematoma [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Axial CT scan showing non-depressed linear skull fracture (arrow) of the skull base involving the foramen magnum. This injury pattern is concerning for associated spinal fracture, cord injury, and blunt cerebrovascular injury [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Axial CT scan showing non-depressed linear skull fracture (arrow) of the skull base involving the foramen magnum. This injury pattern is concerning for associated spinal fracture, cord injury, and blunt cerebrovascular injury [Citation ends].

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer