Recommendations

Key Recommendations

Recognise that episodic right upper quadrant (RUQ) or epigastric pain is the most common symptom of cholelithiasis and results from either obstruction of the cystic duct or obstruction and/or passage of a gallstone through the common bile duct. Biliary pain:[1]

Radiates to the right back or shoulder

Responds to analgesia

Typically occurs approximately 1 hour after consumption of food, often in the evening

May wake the patient from sleep

May be accompanied by nausea

Becomes increasingly intense and then stabilises

Typically lasts for at least 15 to 30 minutes and up to several hours.

Note that the presence of these symptoms together with fever and abdominal tenderness indicates that acute cholecystitis has developed. See Acute cholecystitis.

Offer liver function tests and ultrasound to any patient who has suspected gallstone disease.[1][10]

Ensure accurate diagnostic imaging because the most common complications of cholelithiasis and choledocholithiasis may be life-threatening, and their clinical features may overlap. Such complications include:

Acute cholecystitis

Acute cholangitis

Acute pancreatitis

Sepsis

Obstructive jaundice.

If there is a high clinical suspicion of choledocholithiasis but ultrasound fails to detect common bile duct stones, request either magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) or endoscopic ultrasound according to availability and the individual patient’s characteristics.[73]

Be aware that a combination of the following features suggests that a stone may have migrated into the common bile duct (choledocholithiasis):

Biliary pain

Known gallstones

Abnormal liver biochemistry (particularly an elevated bilirubin >68 micromoles/L [>4 mg/dL])[1]

Pancreatic enzyme elevation

Jaundice (if the gallstone causes complete obstruction of the duct).

Be mindful that the clinical features of some of the complications of cholelithiasis and choledocholithiasis may overlap. Serious and sometimes life-threatening complications include:[76]

Acute cholecystitis. For detailed coverage, see Acute cholecystitis.

Typical presenting features include:[1]

Biliary colic >5 hours

Fever or rigors

Murphy’s sign (tenderness in the right upper quadrant below the costal margin on deep inspiration)

Inflammatory signs.

Acute cholangitis. For detailed coverage, see Acute cholangitis.

Charcot's triad is diagnostic:[8]

Fever - usually with rigors

Jaundice

Right upper quadrant pain.

Acute pancreatitis. For detailed coverage, see Acute pancreatitis.

Sepsis. For detailed coverage, see Sepsis in adults.

Think 'Could this be sepsis?' based on acute deterioration in an adult patient in whom there is clinical evidence or strong suspicion of infection.[77][78][79]

Use a systematic approach, alongside your clinical judgement, for assessment; urgently consult a senior clinical decision-maker (e.g., ST4 level doctor in the UK) if you suspect sepsis.[78][79][80][81]

Refer to local guidelines for the recommended approach at your institution for assessment and management of the patient with suspected sepsis.

Obstructive jaundice. For detailed coverage, see Assessment of jaundice.

Typical presenting features include:[8]

Jaundice

Dark urine

Pale stools.

Practical tip

Pain of short duration (<15-30 minutes) is unlikely to be biliary colic, while pain >8 hours suggests acute cholecystitis or another major complication.[8] See our topics Acute cholecystitis, Acute cholangitis, and Acute Pancreatitis.

Recognise that pain may be biliary in origin if it has some or all of the following features:[1]

Arises in the RUQ or epigastric area

Is episodic

Radiates through to the right back or shoulder

Responds to analgesia

Is constant, beginning abruptly or becoming increasingly intense before stabilising

Typically lasts for at least 15 to 30 minutes and up to several hours (>8 hours suggests acute cholecystitis)[8]

May occur approximately 1 hour after eating, often in the evening

May wake the patient from sleep

May be accompanied by nausea and/or vomiting.

Note that the presence of these symptoms together with fever and abdominal tenderness indicates that acute cholecystitis has developed.

Acute cholecystitis requires different management to uncomplicated symptomatic cholelithiasis. See Acute cholecystitis.

Dyspepsia, heartburn, flatulence, and bloating might also be present but note that these symptoms are very non-specific for gallstone disease.[1][2]

Identify risk factors for gallstones such as:[1][2][3][4][5][6][19][22][53][55][56]

Increasing age

Female sex

Obesity, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome

Family history

Gene mutations

Pregnancy/exogenous oestrogen

Non-alcoholic liver disease (cirrhosis)

Prolonged fasting/weight loss

Total parenteral nutrition

Medications (e.g., octreotide, glucagon-like peptide-1 analogues, ceftriaxone)

Terminal ileum disease or resection

Haemolytic anaemia (sickle cell anaemia or thalassaemia)

Hispanic and Native-American ethnicity.

When examining the patient, note:

Tenderness to palpation in the RUQ or epigastric area; this is the most common feature in patients with symptomatic cholelithiasis.

Suspect acute cholecystitis if the following are present:

Fever

Murphy’s sign (inspiratory arrest when palpating the gallbladder fossa)

High sensitivity (97%) for acute cholecystitis, but poor specificity (48%).[82]

Suspect acute cholangitis or pancreatitis if the patient is jaundiced, although it can also be present in choledocholithiasis. For detailed coverage, see our topics Acute cholangitis and Acute pancreatitis.

Consider the possibility of gallbladder cancer if a patient has an upper abdominal mass consistent with an enlarged gallbladder.

Follow local protocols for investigation of suspected gallbladder cancer. In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends considering an urgent direct access ultrasound scan, to be performed within 2 weeks.[83]

Laboratory testing

Request liver function tests for any patient with suspected gallstone disease (and for anyone who has abdominal or gastrointestinal symptoms that have been unresponsive to previous management).[10]

Liver biochemistry is usually normal with an episode of simple biliary pain.

Brief biliary obstruction with subsequent stone passage causes an early, transient elevation in alanine aminotransferase before the alkaline phosphatase rises.

Obstructive choledocholithiasis is commonly associated with alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin elevations.

In addition, take blood to identify serious complications.

Full blood count:

The white blood cell (WBC) count is usually normal in an episode of simple biliary pain.

An elevated WBC suggests acute cholecystitis, cholangitis, or pancreatitis (but bear in mind that a normal WBC does not necessarily exclude these).[1]

Serum lipase levels (or amylase if lipase test is unavailable) to exclude pancreatitis if the patient’s pain is located primarily in the epigastric area (with or without radiation to the back):

Serum lipase and amylase have similar sensitivity and specificity for pancreatitis but lipase levels remain elevated for longer (up to 14 days after symptom onset vs. 5 days for amylase), providing a higher likelihood of picking up pancreatitis in patients with a delayed presentation.[84][85][86]

Elevated (>3 times upper limit of normal) in acute pancreatitis.[1]

Abdominal ultrasound

Request ultrasound for any patient with suspected gallstone disease (and for anyone who has abdominal or gastrointestinal symptoms that have been unresponsive to previous management).[1][10] Use the results of ultrasound to guide whether additional imaging is required.[87][88] Targeted point of care ultrasound (POCUS), performed at the bedside, can provide a swift diagnosis and expedite subsequent clinical decision making, enhancing patient care.[87][89]

Abdominal ultrasound has low sensitivity for choledocholithiasis, but accuracy is better for any accompanying bile duct dilation.[90][91]

One Cochrane review of five studies of poor methodological quality and covering 523 patients found that many patients with common bile duct stones will have negative ultrasound and liver function tests. The summary sensitivity for ultrasound was 0.73 (95% CI 0.44 to 0.90).[92]

Further investigation is therefore important if you suspect common bile duct stones clinically.

For acute calculous cholecystitis, abdominal ultrasound has high sensitivity for stones plus distension of the gallbladder lumen, gallbladder wall thickening, pericholecystic fluid, and a positive radiological Murphy sign.[90]

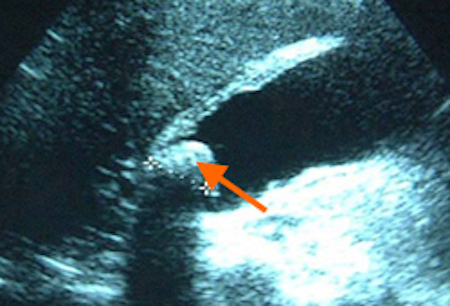

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Ultrasound of acute cholecystitis and presence of gallstones: the arrow points to a gallstone in the fundus of the gallbladder with its echogenic shadow belowCourtesy of Charles Bellows and W. Scott Helton; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Gallbladder ultrasound demonstrating cholelithiasis with characteristic shadowingCourtesy of Kuojen Tsao; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Gallbladder ultrasound demonstrating cholelithiasis with characteristic shadowingCourtesy of Kuojen Tsao; used with permission [Citation ends].

Subsequent imaging

Consider requesting magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) if ultrasound has not detected common bile duct stones but you suspect choledocholithiasis because:[10]

The bile duct is dilated, and/or

Liver function test results are abnormal.

MRCP has a sensitivity of 90% and specificity of 95% for the detection of bile duct stones; however, it has a reduced sensitivity (65%) to detect small (<5 mm) biliary stones.[93][94]

Consider requesting endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) if you suspect choledocholithiasis but MRCP does not identify stones in the bile duct (or after negative ultrasound if MRCP is contraindicated).[10]

Depending on local expertise, some evidence suggests that EUS may provide better diagnostic accuracy for the detection of choledocholithiasis than MRCP.[95][96][97] However, both options are considered to have high diagnostic accuracy and the choice of which to use can be informed by availability and any contraindications.[73]

In experienced hands, EUS more accurately detects those with low to moderate risk (negative ultrasound or MRCP, but positive symptoms and/or blood tests) of having bile duct stones, and who would benefit from a subsequent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).[95][98][99][100][101][102]

EUS-directed ERCP has been proposed as a cost-effective option for patients with a high suspicion of bile duct stones. It offers diagnosis and stone removal in the same session.[97]

EUS is not suitable for patients who have had gastrointestinal bypass procedures.[27]

If you suspect conditions other than gallstone disease, refer the patient for further investigations as necessary.[10]

Consider requesting an abdominal CT scan if the patient has biliary pain and an unremarkable abdominal ultrasound. This may identify potential complications of acute cholecystitis (e.g., emphysema of the gallbladder wall, abscess formation, perforation).[1] See our topic Acute cholecystitis.

CT scan may be normal, or show stones in the gallbladder, and possibly in the bile or pancreatic ducts.

Acute cholangitis will show bile duct dilation with choledocholithiasis.

Acute pancreatitis will be indicated by diffuse or segmental enlargement of the pancreas.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer