Recommendations

Urgent

Assess haemodynamic status immediately, looking for early signs of fluid loss.[18][48]

Early administration of crystalloid intravenous fluids is of critical importance in all patients with acute pancreatitis, however mild.

Evidence suggests early fluid resuscitation reduces the risk of organ failure and deathin acute pancreatitis.

Patients are often not given enough intravenous fluids.[18] This increases the risk of organ failure.

In particular, be aware that patients who have been given adequate analgesia might seem well but still need urgent fluid replacement.[18]

Beware systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and/or multi-organ failure- these are the biggest risk to life in the first week.[18][29][48][49]

You should assess for signs of organ dysfunction immediately on presentation, particularly cardiovascular, respiratory, or renal.

Consider intensive care unit (ICU) transfer for any patient who has SIRS or early signs of organ failure.

Key Recommendations

Presentation

Patients typically present with severe, constant upper abdominal pain, usually sudden in onset and often radiating to the back - with associated nausea/vomiting in 80% of patients.[8][18][48]

Diagnostic confirmation

You can confirm the diagnosis if at least two of these three criteria are met:[18][48]

Upper abdominal pain (epigastric or left upper quadrant)

Elevated serum lipaseor amylase (>3 times upper limit of normal)

Characteristic findings on abdominal imaging (CT, MRCP, ultrasound).

Abdominal imaging

In most patients the diagnosis is made based on clinical symptoms and laboratory testing.

Abdominal imaging is not needed to confirm a diagnosis.[18]

Only request abdominal imaging if there is diagnostic doubt (e.g., atypical presentation or equivocal lipase/amylase result).

Once a diagnosis of acute pancreatitis has been made, a right upper quadrant transabdominal ultrasound must be arranged to check for cholelithiasis.[18][29][48]

Risk stratification

Risk stratify patients into higher and lower risk groups on admission, and in the first 24 hours, using a combination of the SIRS criteria and assessment of risk factors for severe disease.[18][48]

The presence of SIRS on admission is highly sensitive (but not very specific) for predicting mortality.

Scoring tools such as APACHE II, Ranson, or Glasgow are in widespread use but add limited value.[49][50][51][52][53] Their use is not recommended by evidence-based guidelines.[18][48]

Acute pancreatitis can be life-threatening, with a mortality rate of up to 30% in severe cases. However, 80% of patients have mild disease and recover fully within 5 to 7 days.[49]

Causes

Gallstones is the cause in 40% to 70% of patients and excessive alcohol consumption in 25% to 35%.[18]

Upper abdominal pain is the most common presenting symptom of acute pancreatitis.[5][8][9][17][18]

Typically mid-epigastric or left upper quadrant.

Usually sudden onset, increasing in severity over a few hours before plateauing.

Often more acute onset in gallstone pancreatitis than in alcoholic pancreatitis.

Radiates to the back (usually the lower thoracic area but can be a band-like wraparound pattern).[49]

Usually constant and severe but can be variable (in rare cases it is painless).

May be described as “like being stabbed with a knife”.

Typically worsens with movement; some patients find it is eased by taking the fetal position.

Other common presenting symptoms:

Nausea and vomiting may occur in 70% to 80% of cases.[12]

Anorexia:[12]

Decreased appetite is common, usually secondary to nausea, pain, and general malaise.[49]

Severe acute pancreatitis may present with symptoms of organ dysfunction such as agitation and confusion.

Dyspnoea may be present - caused by diaphragmatic splinting secondary to pain or due to pleural effusion or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

Practical tip

The intensity and location of the abdominal pain do not correlate with severity. A small minority of patients present without any abdominal pain.[18]

Pain described as dull, colicky, or located in the lower abdomen is not consistent with acute pancreatitis and suggests an alternative diagnosis.

Your history should include:[1][5][17][48][49]

Alcohol use. Alcohol-related pancreatitis is seen more frequently in men, generally at a younger age than gallstone pancreatitis.

Usually manifests after 4 to 8 years of excessive alcohol intake.

Binge drinking increases the risk.[54]

Relevant medical history:

Previous episodes of acute pancreatitis.

Known gallstone disease or past biliary-colic type pain.

Hypertriglyceridaemia - an uncommon cause.

Recent abdominal trauma or invasive procedures particularly endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) - a rare cause.

Medication (e.g., azathioprine, mercaptopurine).

Recent symptoms of infection (e.g., mumps, mycoplasma, Epstein-Barr virus [a rare cause]).

A detailed family history to rule out collagen vascular diseases, cancer, or hereditary pancreatitis.

Hereditary pancreatitis is very rare and patients usually present in early childhood.

Time since symptoms started:

Most people present within 12 to 24 hours of symptom onset at the latest.[49]

Patients occasionally present after several days of symptoms, in which case their serum lipase/amylase levels may have returned to normal.

Physical findings vary according to the severity of acute pancreatitis, ranging from a generally well patient to a seriously ill patient with abnormal vital signs such as tachycardia and fever.[8]

Close examination is crucial in any patient with suspected acute pancreatitis.

Assess for signs of early fluid loss, hypovolaemic shock, and symptoms suggestive of organ dysfunction (particularly cardiovascular, respiratory or renal) that may require immediate resuscitative measures.[18][48]

Signs of hypovolaemia may include hypotension, oliguria, dry mucous membranes, and decreased skin turgor. The patient may appear tachycardic, tachypnoeic, and sweating, particularly in more severe cases.

Assess for signs of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), which is defined by at least two of the following, and is associated with a worse prognosis:[8][55]

Heart rate >90 bpm

Respiratory rate >20 breaths/minute (or PaCO2 <32 mmHg)

Temperature >38°C or <36°C

WBC count >12 x 109/L or <4 x 109/L

Abdominal examination may reveal a tender and distended abdomen with diminished bowel sounds (if an ileus has developed) and voluntary guarding on palpation of the upper abdomen.

Pulse oximetry often shows hypoxaemia and a need for supplemental oxygen.

Patients with acute pancreatitis are at high risk of hypoxaemia because of one or more of: abdominal splinting, atelectasia, pulmonary oedema, acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Signs of pleural effusion include localised reduced air entry and dullness to percussion (more common on the left). Seen in up to 50% of patients with acute pancreatitis.[6]

Jaundice may be present in severe gallstone pancreatitis.

Practical tip

Because of the anatomical location of the pancreas, any guarding on abdominal palpation may be less intense than expected for the degree of pain the patient is experiencing.

Rare signs might include:

Facial muscle spasm when facial nerve is tapped (Chvostek’s sign).

Although previously linked with hypocalcaemia, Chvostek’s sign appears to have poor sensitivity and specificity.[56]

Complicated haemorrhagic pancreatitis is very rare and may exhibit ecchymotic bruising and discolouration of several areas due to exudates from pancreatic necrosis.

These cutaneous manifestations are only seen in around 1% of cases, may not be seen until 24 to 48 hours of symptom onset, and are not specific to acute pancreatitis.[57]

The areas that may be affected include:[9][12]

The periumbilical skin (Cullen’s sign)

Both flanks (Grey-Turner’s sign)

Over the inguinal ligament (Fox’s sign).

Demonstration of Chvostek's sign: twitching of the ipsilateral facial muscles in reponse to tapping the face anteriorly to the ear and below the zygomatic bone.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Grey-Turner's sign: discoloration of flank in patient with acute pancreatitisFrom BMJ 2001;322:595; used with permission [Citation ends].

Laboratory work-up

Any patient with an acute abdomen should have a full blood count with differential and a blood chemistry including renal, liver, and pancreatic function tests.

Diagnostic confirmation

Serum lipase or amylase

An elevated level of either of these two pancreatic enzymes (>3 times upper limit of normal) confirms the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis in a patient with upper abdominal pain.[29][48]

Patients with diabetes have higher median lipase levels and may need a higher diagnostic threshold (>3-5 times upper limit of normal).[18]

The accuracy of these tests decreases with time since symptom onset. Ask for additional investigations if you still suspect acute pancreatitis, regardless of the test result.[58]

Use serum lipase testing (if available) in preference to serum amylase.[18]

Serum lipase and amylase have similar sensitivity and specificity but lipase levels remain elevated for longer (up to 14 days after symptom onset vs. 5 days for amylase), providing a higher likelihood of picking up the diagnosis in patients with a delayed presentation.[58]

Practical tip

Beware false positive and false negative results. Always take account of the full clinical picture.

Sensitivity of lipase/amylase results:

Up to one quarter of people with acute pancreatitis have lipase/amylase levels that remain within the normal range, leading to a risk of missing the diagnosis.[58] Have a low threshold for admitting patients whose symptoms are suggestive of acute pancreatitis, even if serum lipase and/or amylase tests are normal. Abdominal imaging, such as contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) is recommended for patients in whom there is diagnostic doubt.[18][48]

Serum pancreatic enzyme levels may remain in the normal range in alcohol-related acute pancreatitis (particularly in cases of acute-on-chronic pancreatitis) and in patients with hypertriglyceridaemia (a rare cause).[18]

Specificity of lipase/amylase results:

Around 1 in 10 patients with acute-onset abdominal pain due to another condition will have lipase/amylase levels above the diagnostic threshold for acute pancreatitis. Always consider other possible acute surgical emergencies.

Serum pancreatic enzyme levels can be raised in a variety of acute surgical and other conditions (e.g., impaired renal function, acute appendicitis, cholecystitis, intestinal obstruction, peptic ulcer, salivary gland disease).[18] It is therefore important to consider alternative diagnoses even if lipase/amylase level is elevated.[58]

Evidence: Sensitivity and specificity of lipase/amylase

Lipase and amylase have similar sensitivity and specificity.

A Cochrane review of 10 studies covering 5,056 patients presenting to the emergency department with acute-onset abdominal pain found:[58]

A sensitivity on admission of 72% for amylase (95% CI, 59% to 82%) and 79% for lipase (95% CI, 54% to 92%), based on the accepted diagnostic threshold (>3 times upper limit of normal).

A specificity on admission of 93% for amylase (95% CI, 66% to 99%) and 89% for lipase (95% CI, 46% to 99%), based on the accepted diagnostic threshold for acute pancreatitis (>3 times upper limit of normal).[58]

Markers of disease severity/prognosis

Full blood count

Leukocytosis with left shift (increase in ratio of immature to mature neutrophils and macrophages) is often seen in acute pancreatitis.

WBC count >12 x 109/L or <4 x 109/L is one of the four criteria for identifying SIRS (two or more must be present).[55]

Haematocrit may be elevated (as a result of dehydration/hypovolaemia) or lower than normal.

Elevated haematocrit (>44%) resulting from haemoconcentration due to third space fluid loss is an independent predictor of severity of acute pancreatitis and the risk of developing necrotising pancreatitis.[18][29][59][60]

C-reactive protein (CRP)

Sometimes used as an early indicator of severity and to monitor progression of inflammation.[61]

CRP >200 mg/L indicates a high risk of developing pancreatic necrosis.[62]

The diagnostic test accuracy of CRP for pancreatic necrosis has not been reliably determined.[62] It may take 72 hours after symptom onset to become accurate as an inflammatory marker.[18][63] CRP ≥150 mg/L on day 3 of presentation can be used as a prognostic factor for severe acute pancreatitis.[29]

Urea/creatinine

Elevated creatinine and urea suggest dehydration/hypovolaemia and increased risk for development of severe disease.[18]

Urea >7.14 mmol/L (or rising) or creatinine ≥2 mg/dL indicates renal failure.

Arterial blood gas

PaO2 <60 mmHg is a sign of organ failure.[18]

Patients may be hypoxaemic, requiring supplemental oxygen. If the patient shows signs of deterioration, consider the need for blood gas analysis (arterial or venous) to assess both oxygenation and acid-base status.[5]

Other serum tests to determine the aetiology[48]

Liver function tests (LFTs)

Elevated ALT (>3 times upper limit of normal) predicts gallstones as the cause of acute pancreatitis in over 85% of patients.[48][49]

However, the specificity for pancreatitis is low.[2] In the absence of choledocholithiasis, LFTs are usually normal, but a slight increase in alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin may be seen.

Calcium

Hypercalcaemia, a rare cause of acute pancreatitis, may be identified.

Triglycerides

Check triglyceride levels if a gallstone or alcohol-related cause is not apparent.[18]

Primary or secondary hypertriglyceridaemia is an uncommon cause of acute pancreatitis (accounting for 1% to 4% of episodes). You should only consider it as a possible aetiology in a patient with triglyceride levels above 11.3 mmol/L.[18][29]

Imaging

Do not use abdominal imaging to confirm a diagnosis of acute pancreatitis unless there is diagnostic uncertainty or a failure to respond to treatment.[18]

All patients with acute pancreatitis need transabdominal ultrasound to confirm or exclude cholelithiasis.[18][29][48]

Imaging investigations recommended for all patients

Abdominal ultrasound

Request a right upper quadrant abdominal ultrasound on admission for any patient with a diagnosis of acute pancreatitis, to look for biliary aetiology.[18][29][48]

Early detection of gallstones will ensure a plan is put in place for their definitive management, usually by cholecystectomy, to prevent further attacks of pancreatitis and potential biliary sepsis.[18]

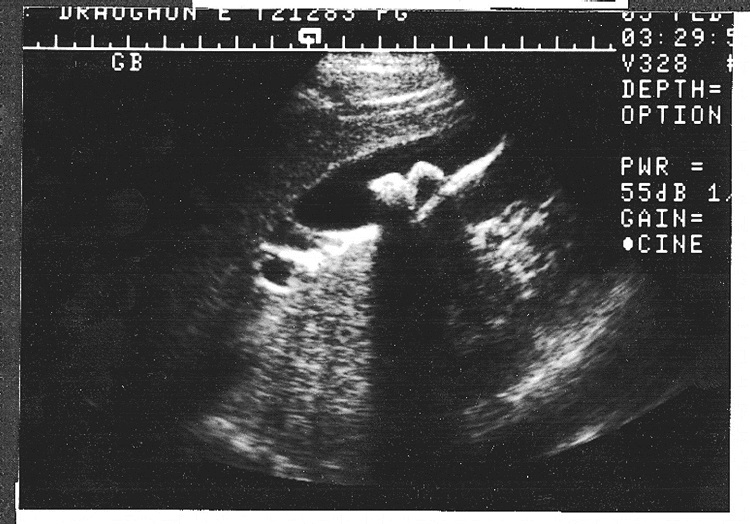

Ultrasound is inexpensive, easy to perform at the bedside, and allows examination of the gallbladder and bile duct system. Its sensitivity in detecting pancreatitis is 62% to 95%. However, it is limited by obesity and bowel gas, and is operator-dependent.[67][68] It also has poor sensitivity, with a high risk of false negatives during the acute phase.[69]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Transabdominal ultrasound revealing gallstones (with characteristic acoustic shadowing) in a patient with acute pancreatitis)From BMJ 1998;316:44; used with permission [Citation ends].

Chest plain film radiographs

Radiographic studies are not used for diagnosis of acute pancreatitis but may identify possible causative factors and/or exclude other diagnoses.

A chest x-ray may show pleural effusion and basal atelectasis and sometimes an elevated hemidiaphragm.[67]

Imaging investigations that should be reserved for specific circumstances

Abdominal CT scan (CECT) for initial diagnosis

Most patients do not need contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) as diagnosis is usually based on clinical presentation and serum lipase/amylase.[48]

CECT has a sensitivity of 87% to 90% and specificity of 90% to 92% for confirming acute pancreatitis.[52]

An early CECT is indicated where there is diagnostic doubt, for example:[18][29][48][49]

An atypical clinical presentation.

Equivocal serum lipase/amylase results (more likely in patients who present late).

To rule out bowel ischaemia or intra-abdominal perforations in a patient presenting with both acute pancreatitis and acute abdomen.

Note that an early CECT scan done for diagnosis should never be used to assess disease severity because necrosis generally takes around 5 days to develop.

Evidence: Early CECT

Routine use of early CECT may be detrimental.

There is no evidence to suggest that routine early CT improves clinical outcomes in acute pancreatitis. Conversely, there is some evidence to suggest that early (inappropriate) CT scanning has low diagnostic yield without influencing ongoing management decisions and can result in a longer hospital stay.[29][48][70][71]

Practical tip

You should consider the possibility of a pancreatic tumour in any patient aged over 40 years if another cause for acute pancreatitis cannot be found after initial laboratory tests and abdominal imaging.[18]

CECT for post-admission assessment of disease severity

CECT is also indicated to assess disease severity and detect complications in any patient with presumed acute pancreatitis who fails to improve or if there is clinical deterioration.[48]

In UK practice, in line with recommendations from the International Association of Pancreatology/American Pancreatic Association and the World Society of Emergency Surgery, CECT for the purpose of assessing disease severity is not performed until 72 to 96 hours after the onset of symptoms, by which time the complete extent of necrosis should be visible.[29][48] An earlier CECT for assessing disease severity might be appropriate if there is clinical concern. Follow your local protocols.

CECT to identify complications

CECT is also recommended in the late phase of acute pancreatitis (>1 week after symptom onset) to look for local complications, particularly in patients with signs or symptoms of systemic disturbance or organ failure.[48][49]

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)

Use EUS or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) in preference to CECT to screen for choledocholithiasis if it is highly suspected in the absence of cholangitis and/or jaundice.[18]

EUS is indicated in patients considered to have idiopathic acute pancreatitis to exclude strictures, occult biliary microlithiasis, neoplasms, and chronic pancreatitis.[48]

A patient is considered to have idiopathic acute pancreatitis after a negative routine work-up including laboratory tests (including lipid and calcium level) and imaging (transabdominal ultrasound and CECT).[48]

Evidence: EUS for diagnosis of idiopathic acute pancreatitis

EUS performs well in establishing the aetiology of idiopathic cases.

A 2018 meta-analysis comparing EUS with MRCP in idiopathic acute pancreatitis found both had a role in establishing the aetiology but EUS had higher diagnostic accuracy than MRCP (64% vs. 34%) and should be preferred for establishing possible biliary disease or chronic pancreatitis.[72]

A systematic review of five studies (416 patients) with idiopathic acute pancreatitis reported a diagnostic yield of 32% to 88% for EUS in detecting biliary sludge, common bile duct stones, or chronic pancreatitis.[73]

Guidelines differ on the role of endoscopic investigations in patients with idiopathic acute pancreatitis for which an aetiology remains unclear after initial laboratory and imaging tests. The International Association of Pancreatology/American Pancreatic Association (IAP/APA) 2013 guideline recommends EUS in this scenario.[48] However, the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) 2013 guideline recommends limiting the use of endoscopic investigations in this patient group on the basis that the balance of risks and benefits remains unclear. Where such investigations are performed, the ACG recommends they should only take place at pancreatic disease centres of excellence.[18]

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP)

Use MRCP if CECT is contraindicated (e.g., renal insufficiency, contrast allergy).

MRCP and CECT are comparable in the early assessment of acute pancreatitis.[74]

MRCP is also gaining favour over CECT in some centres, due to better imaging of biliary and pancreatic stones (down to 3 mm diameter), as well as better characterisation of solid versus cystic lesions.[75]

EUS or MRCP is preferred to CECT to screen for choledocholithiasis if it is highly suspected in the absence of cholangitis and/or jaundice.[18]

In patients with idiopathic acute pancreatitis who have had a negative routine work-up (laboratory tests, repeat abdominal ultrasound, and CECT if performed) and negative endoscopic ultrasound, secretin-stimulated MRCP is recommended to identify rare morphological abnormalities or pancreatobiliary tumour. This is usually done after the patient has recovered fully from the acute phase.[18][48]

Evidence: MRCP for diagnosis of idiopathic acute pancreatitis

Secretin-stimulated MRCP is useful in diagnosing anatomical causes.

A 2018 meta-analysis comparing EUS with MRCP in idiopathic acute pancreatitis found that although EUS had higher diagnostic accuracy than MRCP overall (64% vs. 34%), secretin-stimulated MRCP was superior to EUS and standard MRCP in diagnosing anatomical alterations in the biliopancreatic duct system (e.g., pancreatic divisum).[72]

Emerging tests

Urinary trypsinogen-2 (>50 nanograms/mL) seems to be at least as sensitive and specific as serum lipase and amylase (both at the standard threshold of 3 times the upper limit of normal) for the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis.[48][58]

It is a rapid and non-invasive bedside test but is not yet widely available for clinical use.

A meta-analysis reported a pooled sensitivity of 82% and specificity of 94% for diagnosing acute pancreatitis.[76]

Interleukin-6, interleukin-8, and interleukin-10 may be predictive serum markers for the development of severe acute pancreatitis.[77][78]

One study reported a sensitivity of 81% to 88% and specificity of 75% to 85% for IL-6, and a sensitivity of 65% to 70% and specificity of 69% to 91% for IL-8, for prediction of severe acute pancreatitis.[77]

Use of SIRS for early identification of high-risk patients

Perform risk stratification on admission and in the first 24 hours using a combination of SIRS criteria and patient risk factors.[18][48]

SIRS criteria.[55] Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) is defined by the presence of any two or more of the following four criteria:

Heart rate >90 bpm

Respiratory rate >20 breaths/minute (or PaCO2 <32 mmHg)

Temperature >38°C or <36°C

WBC count >12 x 109/L or <4 x 109/L.

Patient characteristics associated with increased risk of severe disease:[79][80][81][82][83]

Age >55 years

Obesity (BMI >30)

Altered mental status

Comorbid disease.

Early prediction of which patients with acute pancreatitis will go on to develop severe disease is very difficult. Nonetheless, risk stratification should be performed so that treatment setting and management decisions can be tailored to the level of risk.[18][48]

The most significant risk in the early phase of acute pancreatitis (<1 week) is from SIRS-related organ failure.

The reversal of early organ failure has been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality.[18][84][85] Looking for SIRS markers is therefore critical in determining disease severity.

The presence of SIRS at admission has a high sensitivity for predicting organ failure and mortality risk in acute pancreatitis (100% sensitivity for predicting mortality was seen in one study).[86]

Evidence: Specificity of SIRS for predicting severe disease

The presence of SIRS is less important than its persistence.

SIRS lacks specificity for predicting severe disease (31% in one study) and mortality because the presence of SIRS is not as important as its persistence.[86] In one study of 759 patients with acute pancreatitis, patients without SIRS had a mortality of 0.7% whereas transient SIRS (<48 hours) was associated with a mortality of 8% and persistent SIRS (>48 hour) with a mortality of 25%.[87]

The SIRS criteria are well known and easy to use so are preferred for daily clinical practice over specific scoring tools such as APACHE II or Glasgow Scores.[48]

Guidelines recommend that you should also be aware of patient characteristics that are associated with a higher risk of developing severe disease.[18][48]

Approximately 80% of patients with acute pancreatitis will have a mild episode that only requires brief admission and will recover within 3 to 7 days.[49]

Mild acute pancreatitis is defined as no organ failure and no local complications.[2]

Approximately 20% of patients will develop moderately severe or severe acute pancreatitis.

Moderately severe pancreatitis is defined as transient organ failure (<48 hours) and/or local complications.[2]

Severe acute pancreatitis is defined as persistent organ failure (>48 hours). These patients have a mortality rate of up to 30%.[8][49]

Under the revised Atlanta Criteria for acute pancreatitis, organ failure is defined as a Modified Marshall Score of ≥2 on any one of three organ systems (cardiovascular, renal, respiratory).

In everyday clinical practice, it is more practical to continue using the original Atlanta Criteria for organ failure:[18]

Shock: SBP ≤90 mmHg

Pulmonary insufficiency: PaO2 ≤60%

Renal failure: creatinine ≥2 mg/dL

Gastrointestinal bleeding: >500 mL blood loss in 24 hours.

You should immediately transfer to ICU any patient who meets the original or revised Atlanta Criteria for organ failure or who fulfils one or more of the below criteria:[48]

Heart rate <40 bpm or >150 bpm

Systolic arterial pressure <80 mmHg or mean arterial pressure <60 mmHg, or diastolic arterial pressure >120 mmHg

Respiratory rate >35 breaths/minute

Serum sodium <110 mmol/L or >170 mmol/L

Serum potassium <2 mmol/L or >7 mmol/L pH <7.1 or >7.7

Serum glucose >44.4 mmol/L

Serum calcium >3.75 mmol/L

Anuria

Coma.

Prognostic scoring systems and their limitations

Clinical scoring systems for severity/prognostication are best avoided as they provide little additional information and can delay appropriate management.[18][48][51]

Such scoring systems typically require 48 hours to pass before they are accurate, by which time severe disease will become clinically obvious regardless of the score.[18]

There are several such scoring systems in widespread use (the most common being APACHE II, Ranson, and Glasgow) so check local guidance. None of these scores has been shown to be clearly superior or inferior to SIRS for predicting severe disease.[48][49]

Scores that can be used in the emergency department or within first 24 hours

APACHE II Score[50] [ APACHE II scoring system Opens in new window ]

Can be assessed within 24 hours of admission.

A score of 8 or higher predicts severe disease and increased mortality risk.

Performs no better than a standard early warning score in predicting severe acute pancreatitis.[49]

Harmless Acute Pancreatitis Score[88] MDCalc: Harmless Acute Pancreatitis Score (HAPS) Opens in new window

Can be used for early identification of patients at low risk of progression to severe disease.

Based on three factors: creatinine level in normal range; haematocrit in normal range; no rebound abdominal tenderness or guarding.

Bedside Index of Severity in Acute Pancreatitis (BISAP) [ Bedside Index of Severity in Acute Pancreatitis (BISAP) Score Opens in new window ]

For use in the first 24 hours.

Five-factor scoring system based on urea level >25 mg/dL; impaired mental status; presence of SIRS; age >60 years; pleural effusion on chest x-ray. A score of 2 or higher is associated with a significantly higher risk of organ failure and death.[88]

Scores for use at 48 hours or later

Ranson Criteria MDCalc: Ranson's criteria for pancreatitis mortality Opens in new window

Glasgow (Imrie) Score MDCalc: Glasgow-Imrie criteria for severity of acute pancreatitis Opens in new window

See Management.

How to take a venous blood sample from the antecubital fossa using a vacuum needle.

How to obtain an arterial blood sample from the radial artery.

How to perform a femoral artery puncture to collect a sample of arterial blood.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer