Aetiology

The major causative pathogens of acute pyelonephritis are gram-negative bacteria. Escherichia coli causes approximately 60% to 80% of uncomplicated infections.[8] Attention has recently focused on uropathogenic E coli as being responsible for a significant proportion of treatment-resistant infections.[9][10][11] Other gram-negative pathogens include Proteus mirabilis (responsible for about 5% of infections) as well as Klebsiella (approximately 10%), Enterobacter, and Pseudomonas species.[12] Less commonly, gram-positive bacteria such as Enterococcus faecalis, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, and Staphylococcus aureus may be seen.

Organisms differ in complicated cases and include a broad range of pathogens, many of which are resistant to multiple antibiotic agents and are more likely to be associated with complicated disease. In older hospitalised patients, because of increased usage of catheters (portals to infection), gram-negative organisms such as P mirabilis, Klebsiella, Serratia, and Pseudomonas are more common causative agents, and only 60% of cases are due to E coli.[2][13] In people with diabetes, infections are predominantly a result of Klebsiella, Enterobacter, Clostridium, or Candida. Those with immunosuppression (e.g., HIV, malignancy, transplantation) are especially prone to silent infections as a result of non-enteric, aerobic, gram-negative rods and Candida.

Pathophysiology

Acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis most often develops as a result of an ascending urinary tract infection. In these cases, symptoms of cystitis often precede acute pyelonephritis, particularly in patients with uncomplicated infections. Alternatively, pathogenesis may involve haematogenous seeding of the kidneys in patients with bacteraemia. Typically, in women who develop acute pyelonephritis, pathogens first colonise the distal urethra and vaginal introitus and then ascend via the bladder and ureters to the kidney. Women with cystitis-like symptoms (e.g., frequency, urgency, and dysuria) commonly (30%) have asymptomatic pyelonephritis, rarely causing kidney damage.

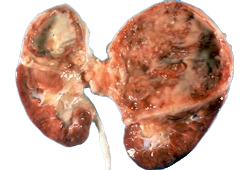

Men are more prone to prostatitis and benign prostatic hyperplasia, which cause a urethral obstruction leading to bacteriuria and consequently often pyelonephritis. Dilation and obstruction of the ureter cause inflammation of the kidney parenchyma, which is seen on histopathological examination as purulent exudates in the renal tubules.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cross-section of a kidney with acute suppurative pyelonephritis. The white streaks are purulent exudates throughout the kidney, in both the tubules and the interstitiumMcLay RN, Harrison JH, Fermin CD, et al. Tulane gross pathology tutorial. Tulane University School of Medicine; 1997 [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: External surface of the kidney with multifocal irregular, whitish, raised lesions consisting of purulent exudatesMcLay RN, Harrison JH, Fermin CD, et al. Tulane gross pathology tutorial. Tulane University School of Medicine; 1997 [Citation ends].

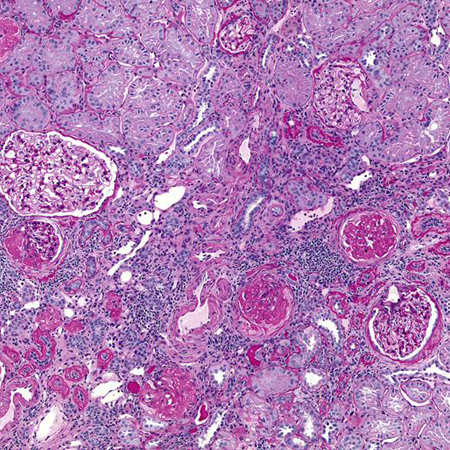

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: External surface of the kidney with multifocal irregular, whitish, raised lesions consisting of purulent exudatesMcLay RN, Harrison JH, Fermin CD, et al. Tulane gross pathology tutorial. Tulane University School of Medicine; 1997 [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Interstitial infiltrates and oedema in acute pyelonephritis. Some glomeruli also show evidence of a second kidney disease, focal glomerulosclerosisCourtesy of Dr Jean L. Olson, Department of Pathology, University of California, San Francisco, CA [Citation ends].

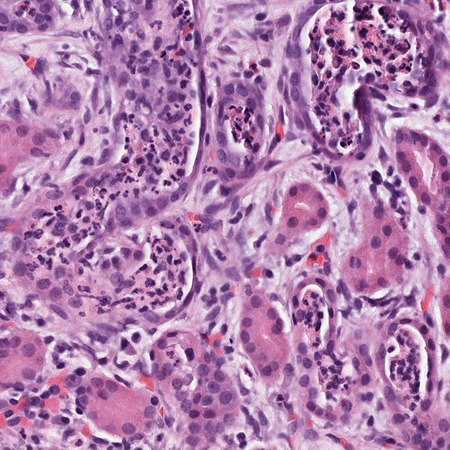

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Interstitial infiltrates and oedema in acute pyelonephritis. Some glomeruli also show evidence of a second kidney disease, focal glomerulosclerosisCourtesy of Dr Jean L. Olson, Department of Pathology, University of California, San Francisco, CA [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Higher magnification: polymorphonuclear cell infiltrates in and around the renal tubulesCourtesy of Dr Jean L. Olson, Department of Pathology, University of California, San Francisco, CA [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Higher magnification: polymorphonuclear cell infiltrates in and around the renal tubulesCourtesy of Dr Jean L. Olson, Department of Pathology, University of California, San Francisco, CA [Citation ends].

Additionally, obstruction as a result of any cause (e.g., calculi, tumour, foreign body, benign prostatic hyperplasia, or neurogenic bladder) often leads to treatment failure and eventual renal abscess, as continued blockage may lead to re-infection. Chronically ill patients and those receiving immunosuppressive therapy are at highest risk.[2] Seeding in the kidney from bone or skin may occur from metastatic staphylococcal or fungal infections as well.

Uropathogenic Escherichia coli are a common cause of infection in patients with normal urinary tract anatomy.[4] The enhanced virulence potential of uropathogenic E coli is thought to derive mainly from factors that enhance the ability of these strains to adhere to and colonise the urinary tract. These factors include flagella, which increase motility, haemolysins that break down red blood cells, and iron-scavenging molecules that pick up the iron released from red cell lysis to use for cell growth and adhesions on the bacterial fimbriae that help the organisms stick to the uroepithelial surface. The proteins required for P-fimbrial biogenesis, a mannose-resistant adhesin of uropathogenic E coli, are encoded by the pap gene cluster codons. P fimbriae appear to play some role in mediating adherence to uroepithelial cells in vivo and establishing an inflammatory response during renal colonisation, thus contributing to kidney damage during acute pyelonephritis.[14] Other properties assist the bacteria in avoiding or subverting host defences, injuring or invading host cells and tissues, and stimulating a noxious inflammatory response.[15] Virulence of uropathogenic E coli has been linked to the presence of pathogenicity islands, unstable large regions of the bacterial genome encoding for these virulence factors, which are present in approximately 80% of E coli strains identified in the blood and urine of patients with acute pyelonephritis.[16] More than 30 bacterial species carrying pathogenicity islands have been described.[17]

Classification

Acute pyelonephritis classification, Medical Clinics of North America, 1995[1]

Uncomplicated acute pyelonephritis: an infection of the upper urinary tract (kidney and renal pelvis) if caused by a typical pathogen in an immunocompetent patient with normal urinary tract anatomy and kidney function.

Complicated acute pyelonephritis: an infection of the upper urinary tract (kidney and renal pelvis) in patients with increased susceptibility or immunocompromise, such that the infection will likely be severe.

Such factors are:

Age

Infants (not covered in this topic)

Older patients (>60 years)

Anatomical abnormality

Vesicoureteric reflux

Polycystic kidney disease

Horseshoe kidney

Double ureter

Ureterocele

Foreign body

Renal stone

Urinary, ureteric, or nephrostomy catheter

Impaired renal function

Immunocompromised

Diabetes mellitus

Sickle cell disease

Transplantation

Malignancy

Chemotherapy

Radiotherapy

Alcohol dependence

HIV

Corticosteroid use

Use of immunosuppressants

Instrumentation

Cystoscopy

Male sex

Recurrent infection

Infection foci in prostate

Anatomical abnormalities

Obstruction

Benign prostatic hypertrophy

Renal stone

Foreign body

Bladder neck obstruction

Posterior ureteral valve

Neurogenic bladder

Pregnancy

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer