Recommendations

Urgent

Arrange immediate bedside echocardiography (requires specialist expertise) and ECG for any patient who is haemodynamically unstable (low blood pressure or shock) or in respiratory failure with suspected acute heart failure as part of looking for life-threatening causes. Life-threatening causes include:[1][4]

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS)[4]

Hypertensive emergency

Rapid arrhythmias or severe bradycardia/conduction disturbance

An acute mechanical cause (e.g., myocardial rupture as a complication of ACS, chest trauma)

Acute pulmonary embolism

Infection (including myocarditis)

Tamponade.

Request urgent critical care/cardiology support for any patient with: [1]

Respiratory distress/failure[22]

Reduced consciousness

Heart rate <40 or >130 bpm[22]

Systolic blood pressure persistently <90 mmHg[22]

Unless known to be usually hypotensive (based on the opinion of our expert adviser)

Signs or symptoms of hypoperfusion - see Shock

Haemodynamic instability

Acute heart failure due to ACS[4]

Persistent life-threatening arrhythmia.

Request serum brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) measurement in the first set of blood tests for all patients with acute breathlessness who may have new acute heart failure.[4][23]

The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends use of N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP).[24]

BNP measurement is useful in differentiating acute heart failure from non-cardiac causes of acute dyspnoea.[1]

Organise rapid transfer to hospital (preferably to a site with a cardiology department and/or a coronary care/intensive care unit) for any patient in the community with suspected acute heart failure.[1]

Acute heart failure is potentially life-threatening and requires urgent evaluation and treatment.

Key Recommendations

Assess for common symptoms and signs of acute heart failure. These include:[1]

Dyspnoea

Orthopnoea

Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea

Ankle swelling

Reduced exercise tolerance

Fatigue

Elevated jugular venous pressure

Third heart sound (gallop rhythm)

Pulmonary crepitations.

Ask about risk factors for heart failure. Established heart failure is unusual in a patient with no relevant medical history.[1]

Establish the patient’s haemodynamic status as this will determine further management. Most patients present with either normal (90-140 mmHg) or hypertensive (>140 mmHg) systolic blood pressure (SBP).

Hypotension (SBP <90 mmHg) is associated with poor prognosis, particularly when hypoperfusion is present.

Always order the following investigations for a patient with new suspected acute heart failure to establish the presence or absence of cardiac abnormalities:[1][23]

ECG

Chest x-ray

N-terminal-proB-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) or BNP and other standard blood tests

Echocardiography.[6]

Once stabilised, use the patient’s left ventricular ejection fraction to guide disease-modifying treatment. Address causative aetiology and relevant comorbidities.[1]

Suspect acute heart failure in any patient with:

Breathlessness[1]

This may be acute but also includes orthopnoea and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea[25]

Ankle swelling[1]

This often reduces when the patient’s legs have been elevated for a sustained period of time (e.g., in bed overnight)

Reduced exercise tolerance[1]

Fatigue, tiredness, increased time to recover after exercise[1]

Less common symptoms, including: wheezing, dizziness, confusion (especially in older patients), loss of appetite, nocturnal ischaemic pain, nocturnal cough (frothy sputum suggests that it is alveolar in origin and not bronchial).[1][25]

Urgently assess for any signs or symptoms related to the underlying cause of acute heart failure.[1][25]

It is important to screen for an underlying cause of heart failure as this may be treatable.[1]

Underlying precipitants/causes of acute heart failure that must be managed immediately to prevent further rapid deterioration (while recognising that any acute heart failure is potentially life-threatening) include:[1]

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS).[4] See Unstable angina, Non-ST elevation myocardial infarction, and ST-elevation myocardial infarction

Hypertensive emergency. See Hypertensive emergencies

Rapid arrhythmias or severe bradycardia/conduction disturbance. See Assessment of tachycardia and Bradycardia

An acute mechanical cause (e.g., myocardial rupture as a complication of ACS [such as free wall rupture], ventricular septal defect or acute mitral regurgitation, chest trauma)

Acute pulmonary embolism. See Pulmonary embolism

Valve disease

Myocarditis. See Myocarditis

Tamponade.

Request urgent critical care/cardiology support for any patient with:[1]

Respiratory distress/failure[22]

Reduced consciousness

Heart rate <40 or >130 bpm[22]

Systolic blood pressure persistently <90 mmHg[22]

Unless known to be usually hypotensive (based on the opinion of our expert adviser)

Signs or symptoms of hypoperfusion.[1] See Assessment of shock

Haemodynamic instability[1]

Acute heart failure due to ACS[4]

Persistent life-threatening arrhythmia.

Check whether the patient has previously been diagnosed and treated for heart failure. If so, ask about:

Current treatment for heart failure and the patient's adherence.

Ask about risk factors for heart failure if the patient has not previously been diagnosed, including:

Previous cardiovascular disease; coronary heart disease is the most common cause of heart failure[10]

Older age[1]

Prevalence of heart failure is ≥10% in people >70 years of age[1]

Diabetes[10]

Family history of ischaemic heart disease or cardiomyopathy[10]

Excessive alcohol intake or smoking[10]

Cardiac arrhythmias including tachyarrhythmia or bradyarrhythmia

History of systemic conditions associated with heart failure (e.g., sarcoidosis and haemochromatosis)

Previous chemotherapy.

Ask about recent drug history. Drugs that may exacerbate heart failure include non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, steroids, diltiazem, and verapamil.[10]

Practical tip

Heart failure is unusual in patients with no relevant medical history.[1]

Assess the degree of dyspnoea, including:

Look for signs of poor perfusion such as:

Cold extremities[1]

Narrow pulse pressure[1]

Confusion (especially in the elderly)[1]

Oliguria[1]

Dizziness[1]

Central cyanosis

Delayed capillary refill time.

Check for signs of congestion such as:

Leg oedema is usually bilateral and pitting

Pulmonary crepitations

Dullness to percussion and decreased air entry in lung bases

Wheezing[26]

Elevated jugular venous pressure

Measure the patient’s blood pressure; haemodynamic status will determine further management.

Most patients present with either normal (90-140 mmHg) or hypertensive (>140 mmHg) systolic blood pressure (SBP).[1]

Hypotension (SBP <90 mmHg) is not always associated with hypoperfusion, as BP may be preserved by compensatory vasoconstriction.[1] See Shock.

Listen to the patient’s heart sounds. Signs of acute heart failure include:

Also listen for potential valvular causes such as aortic stenosis or mitral regurgitation.

Practical tip

The sound of the crackles heard on chest auscultation in heart failure is described as ‘wet’ and sounding like Velcro. Crackles in heart failure are usually fine and quiet rather than the coarse sounds that are more commonly heard in lung disease. They can be mistaken for the bilateral crackles of lung fibrosis, but patients with fibrotic lungs are more likely to be hypoxic with exertional desaturation.

Always check above the level of the patient’s earlobes for a raised jugular venous pressure because this is easily missed. However, a raised jugular venous pressure can be difficult to spot, even for a heart failure specialist.

Always order

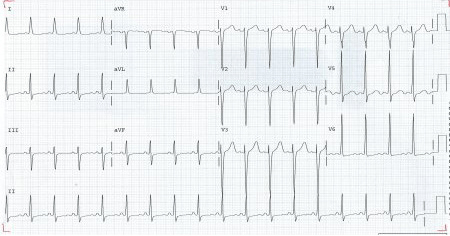

ECG

Record and interpret a 12-lead ECG for all patients with suspected heart failure; monitor this continuously.[1]

Arrange this immediately if the patient is haemodynamically unstable or in respiratory failure to look for any life-threatening cause of acute heart failure (e.g., acute coronary syndrome, particularly ST-elevation myocardial infarction). See ST-elevation myocardial infarction.[1]

Check heart rhythm, heart rate, QRS morphology, and QRS duration, as well as looking for specific abnormalities such as arrhythmias, atrioventricular block, evidence of a previous myocardial infarction (e.g., Q waves), and evidence of left ventricular hypertrophy.[1]

The ECG is usually abnormal in acute heart failure.[1]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: ECG showing left ventricular hypertrophy with sinus tachycardiaFrom the private collections of Syed W. Yusuf, MBBS, MRCPI, and Daniel Lenihan, MD [Citation ends].

Chest x-ray

The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends a chest x-ray for all patients with suspected heart failure.[23] Look for:[27]

Pulmonary congestion

Pleural effusion

Interstitial or alveolar fluid in horizontal fissure

Cardiomegaly.

Practical tip

Be aware that significant left ventricular dysfunction may be present without cardiomegaly on chest x-ray.[27]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest x-ray showing acute pulmonary oedema with increased alveolar markings, fluid in the horizontal fissure, and blunting of the costophrenic anglesFrom the private collections of Syed W. Yusuf, MBBS, MRCPI, and Daniel Lenihan, MD [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest x-ray showing acute pulmonary oedema with increased alveolar markings and bilateral pleural effusionsFrom the private collections of Syed W. Yusuf, MBBS, MRCPI, and Daniel Lenihan, MD [Citation ends].

Blood tests

Natriuretic peptides

Order N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) if available. Brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) or mid-regional pro-atrial natriuretic peptide (MR-proANP) (in some countries) are alternatives.[1][4][23]

Normal levels make the diagnosis of acute heart failure unlikely (normal levels: NT-proBNP <300 ng/L (<300 picograms [pg]/mL); BNP <100 ng/L (<100 pg/mL); MR-proANP <120 ng/L (<120 pg/mL).[1][23] However, elevated levels of natriuretic peptides do not automatically confirm the diagnosis of acute heart failure as they may be associated with a wide variety of cardiac and non-cardiac causes. Low levels of natriuretic peptides can occur in end-stage heart failure, flash pulmonary oedema, or right-sided acute heart failure.[1]

Most older patients presenting to hospital with acute breathlessness have an elevated NT-proBNP so separate ‘rule in’ diagnostic cut-offs are useful in this setting.

If NT-proBNP is significantly elevated (>1800 ng/L [>1800 pg/mL] in patients >75 years; see table below) acute heart failure is likely and should be confirmed by inpatient echocardiography. If the NT-proBNP is intermediate (>300 ng/L [>300 pg/mL] but <1800 ng/L [<1800 pg/mL]), consider other possible causes of breathlessness, but if these are excluded and diagnostic suspicion of heart failure remains, request an echocardiogram.[23]

Age (years) | <50 | 50-75 | >75 |

NT-proBNP level (ng/L or pg/mL) above which acute heart failure is likely[4] | >450 | >900 | >1800 |

Practical tip

Be aware that natriuretic peptides may be raised due to other causes (e.g., acute coronary syndrome, myocarditis, pulmonary embolism, older age, and renal or liver impairment), hence the need for practical ‘rule in’ cut-offs.[1]

Troponin

Measure troponin in all patients with suspected acute heart failure.[22]

Most patients with acute heart failure have an elevated troponin level. As well as diagnosis, troponin may be useful for prognosis; elevated levels are associated with poorer outcomes.[22]

Be aware that interpretation is not straightforward; type 2 myocardial infarction and myocardial injury are common.

Full blood count

Identify anaemia, which can worsen heart failure and also suggest an alternative cause of symptoms, and check iron status (transferrin, ferritin) before discharge.[1]

Electrolytes, urea, and creatinine

Order as a baseline test to inform decisions on drug treatment that may affect renal function (e.g., diuretics, ACE inhibitors), and to exclude concurrent or causative renal failure.

Glucose

Measure blood glucose in all patients with suspected acute heart failure to screen for diabetes.[22]

In practice, also request HbA1c (based on the opinion of our expert).

Liver function tests

Order these for any patient with suspected acute heart failure.

Liver function tests are often elevated due to reduced cardiac output and increased venous congestion. Abnormal liver function tests are associated with a worse prognosis.[1]

Thyroid function tests

Order thyroid-stimulating hormone in any patient with newly diagnosed acute heart failure. Both hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism can cause acute heart failure.[1] See Overview of thyroid dysfunction.

C-reactive protein

Consider ordering C-reactive protein (based on the opinion of our expert).

Inflammation is associated with progression of chronic heart failure.

Levels of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein are raised in patients with acute heart failure.[28]

D-dimer

Indicated in patients with suspicion of acute pulmonary embolism.[22] See Pulmonary embolism.

Echocardiography

Arrange immediate bedside echocardiography for any patient with suspected acute heart failure who is haemodynamically unstable or in respiratory failure.[4] Specialist expertise is required.

If a patient is haemodynamically stable, arrange echocardiography within 48 hours.[6][23]

Echocardiography is used to assess myocardial systolic and diastolic function of both left and right ventricles, assess valvular function, detect intracardiac shunts, and measure left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).[23]

Evaluating the patient’s LVEF has a key role in assessing the severity of any decrease in systolic function and is essential in determining your patient’s long-term management.[1]

Practical tip

The diagnosis of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) requires an LVEF ≤40%. Patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) have clinical signs of heart failure with normal or near-normal LVEF, and evidence of structural and/or functional cardiac abnormalities (including raised natriuretic peptides) in the absence of significant valvular disease. There is an emerging group of patients with heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction (41% to 49%) (HFmrEF) and encouraging data with some therapies recommended for HFrEF. However, current guidelines do not offer strong recommendations regarding HFrEF therapies for these patients.[1]

Consider ordering

Venous or arterial blood gas

Perform an arterial blood gas (ABG) if an accurate measurement of arterial partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) and arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2) is needed.[1]

Consider measurement of blood pH and PaCO2 even if the patient does not have cardiogenic shock, especially if respiratory failure is suspected.[1]

Do not routinely perform an ABG. Venous blood gas may acceptably indicate pH and PaCO2.

A blood gas may show:

Hypoxaemia

PaO2 <10.67 kPa (<80 mmHg) on arterial blood gas)

Metabolic acidosis with raised lactate in a patient with hypoperfusion

pH <7.35, lactate >2 mmol/L (>18 mg/dL)

Type I or type II respiratory failure

Type I respiratory failure: PaO2 <8 kPa (<60 mmHg)

Type II respiratory failure: PaCO2 >6.65 kPa (>50 mmHg).

Blood tests screening for myocarditis

Consider blood tests screening for acute myocarditis if you suspect myocarditis as a cause of acute heart failure. These include screening for viruses that cause acute myocarditis, including coxsackievirus group B, HIV, cytomegalovirus, Ebstein-Barr virus, hepatitis, echovirus, adenovirus, enterovirus, human herpes virus 6, parvovirus B19, and influenza viruses. See Myocarditis.

Bedside thoracic ultrasound

Bedside thoracic ultrasound is useful in countries with no access to BNP/NT-proBNP testing for detecting signs of interstitial oedema and pleural effusion in heart failure if specialist expertise is available.[1][4]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer