Recommendations

Urgent

Suspect sepsis based on acute deterioration in a patient in whom there is clinical evidence or strong suspicion of infection.[41]

Think ‘Could this be sepsis?’ whenever an acutely unwell person presents with likely infection, even if their temperature is normal.[3][41][42] Remember that sepsis represents the severe, life-threatening end of infection.[4]

Have a low threshold for suspicion.

The key to improving outcomes is early recognition and prompt treatment, as appropriate, of patients with suspected or confirmed infection who are deteriorating and at risk of organ dysfunction.[3][43]

By the time the diagnosis becomes obvious, with multiple abnormal physiological parameters, risk of mortality is very high.[41]

Your clinical judgement is crucial to how you approach the individual patient.[41]

Whenever an acutely ill patient presents with a known infection, presents with symptoms or signs of infection, or is at high risk of infection, use a systematic approach to assess the risk of deterioration due to sepsis.[42][43] NHS England: Sepsis Opens in new window

Always assess and record temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, level of consciousness, hourly fluid balance (including urine output), and oxygen saturations.[3]

Use the findings to risk stratify patients so that immediate sepsis treatment can be prioritised for those at high risk of deterioration.[3][43] Always use your clinical judgement.[3][41]

Urgent: in hospital

Consult local guidelines for the recommended approach for assessing acute deterioration. Use your clinical judgement alongside a validated scoring system such as the National Early Warning Score 2 ( NEWS2) (see Risk stratification below), which is recommended by NHS England and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).[3][41][43][44] Determine urgency of initial treatment by assessing severity of illness at presentation; in the UK, use NEWS2 scores as part of wider clinical assessment.[3][45] In a patient with a known or likely infection, a NEWS2 score of 5 or more is likely to indicate sepsis.[42]

Arrange urgent assessment by a senior clinical decision-maker (e.g., ST3 level doctor in the UK) for any patient with an aggregate NEWS2 score of 5 or more calculated on initial assessment in the accident and emergency department or on ward deterioration.[3][41][45] This review should take place:[3][45]

Within 30 minutes of initial severity assessment for any patient with an aggregate NEWS2 score of 7 or more; or with a score of 5 or 6 if there is clinical or carer concern, continuing deterioration or lack of improvement, surgically remediable sepsis, neutropenia, or blood gas/laboratory evidence of organ dysfunction (including elevated serum lactate)

A patient is also at high risk of severe illness or death from sepsis if they have a NEWS2 score below 7 and a single parameter contributes 3 points to their NEWS2 score and a medical review has confirmed that they are at high risk.

Ensure a senior clinical decision-maker (e.g., ST3 level doctor in the UK) attends in person within 1 hour of any intervention if there is no improvement in the patient’s condition. Refer to or discuss with a critical care consultant or team.[3] Inform the responsible consultant.[3]

Within 1 hour of initial severity assessment for any patient with an aggregate NEWS2 score of 5 or 6.

The higher the aggregate NEWS2 score, the higher the risk of clinical deterioration.[41][42]

Although a senior decision-maker should be involved and aware at an early stage for all patients at high risk of severe illness or death, review may be carried out by a clinician with core competencies in the care of acutely ill patients (FY2 level or above in the UK) to urgently assess the person's condition and think about alternative diagnoses to sepsis.[3]

Patients with critical illness (septic shock, sepsis associated with rapid deterioration, or NEWS2 score of 7 or more) are most likely to benefit from rapid administration of antibiotics.[45]

If sepsis is strongly suspected (i.e., new organ dysfunction related to severe infection) in an acutely unwell and rapidly deteriorating patient with a NEWS2 score of 5 or more, the team should act promptly. Establish venous access early to enable initial assessment and treatment actions according to the timeframes below:[41][43][45][46][47]

Within 1 hour of initial severity assessment for patients with a NEWS2 score of 7 or more calculated on initial assessment in the accident and emergency department or on ward deterioration (or with a score of 5 or 6 if there are additional clinical or carer concerns, continuing deterioration or lack of improvement, surgically remediable sepsis, neutropenia, or blood gas/laboratory evidence of organ dysfunction)

A patient is also at high risk of severe illness or death from sepsis if they have a NEWS2 score below 7 and a single parameter contributes 3 points to their NEWS2 score and a medical review has confirmed that they are at high risk.[3]

Within 3 hours for patients with a NEWS2 score of 5 or 6.

Carry out the following investigations:[3][41][46][47]

Blood cultures: take two sets of blood cultures

Take bloods immediately, preferably before antibiotics are started (although sampling should not delay the administration of antibiotics)[3][43][48][49]

Prioritise filling the aerobic bottle before filling the anaerobic one

If a line infection is suspected, it is good practice to remove the line and culture the tip

Lactate level: measure serum lactate, on a blood gas, to determine the severity of sepsis and monitor the patient’s response to treatment

Lactate is a marker of stress and may be a marker of a worse prognosis (as a reflection of the degree of stress)

Lactate may normalise quickly after fluid resuscitation. Patients whose lactate levels fail to normalise after adequate fluids are the group that fare worst

Lactate >4 mmol/L (>36 mg/dL) is associated with worse outcomes

Do not be falsely reassured by a normal lactate (<2 mmol/L [<18 mg/dL])

This does not rule out the patient being acutely unwell or at risk of deterioration or death due to organ dysfunction. Lactate helps to provide an overall picture of a patient's prognosis but you must take into account the full clinical picture of the individual patient in front of you including their NEWS2 score to determine when/whether to escalate treatment.[3]

Hourly urine output: assess the patient’s urine output

A low urine output may suggest intravascular volume depletion or renal failure

Consider catheterising the patient on presentation if they are shocked/confused/oliguric/critically unwell.

Start the following treatments:[3][41][46][47]

Broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics (after taking blood cultures), if there is evidence of a bacterial infection. Only give antibiotics if they have not been given before for this episode of sepsis.[3]

Intravenous fluids, if there is any sign of circulatory insufficiency

Oxygen, if needed.[50]

Beware septic shock, a subtype of sepsis with a much higher mortality.[1][42]

Characterised by profound circulatory and metabolic abnormalities.

Presents with persistent hypotension and serum lactate >2 mmol/L (>18 mg/dL) despite adequate fluid resuscitation, with a need for vasopressors to maintain mean arterial pressure at 65 mmHg or above.[1]

Patients with septic shock are likely to benefit from rapid (within 1 hour of presentation) empirical broad-spectrum antimicrobials.[45]

See Shock

Early and adequate source identification and control is critical. Undertake intensive efforts, including imaging, to attempt to identify the source of infection in all patients with sepsis.[3][43]

Consider the need for urgent source control as soon as the patient is stable.

Urgent: in the community

Use your clinical judgement supported by formal risk stratification (e.g., NEWS2), which is endorsed by NHS England and supported by the Royal College of General Practitioners in the UK, or use the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) high-risk criteria (see Risk stratification below) to identify which patients are at high risk of deterioration due to sepsis.[3][41][51]

Refer for emergency medical care in hospital (usually by blue-light ambulance in the UK) any patient who is acutely ill with a suspected infection and is:[3]

Deemed to be at high risk of deterioration due to organ dysfunction (as measured by risk stratification)

At risk of neutropenic sepsis

See Febrile neutropenia.

Communicate your concern to the ambulance service and hospital colleagues by using the words 'suspected sepsis', and offer the outcome of your physiological assessment or NEWS2 score.[51]

Key Recommendations

Sepsis is a medical emergency with reported high mortality.[3][43]

Sepsis is present in many hospitalisations that culminate in death. In 2015, 23,135 people in the UK died from sepsis, where sepsis was an underlying or contributory cause of death. NHS England: Sepsis Opens in new window The true contribution of sepsis to these deaths is unknown. Most underlying causes of death in people with sepsis are thought to relate to severe chronic comorbidities and frailty.[5][7][8]

Make all efforts to determine escalation status and appropriate potential limits of treatment; ensure any initiated treatments are appropriate for the individual patient.

Presentation

Have a high index of suspicion for sepsis as clinical presentation can be subtle.[3][21]

Your patient may present with non-specific or non-localised symptoms (e.g., acutely unwell with a normal temperature) or there may be severe signs with evidence of multi-organ dysfunction and shock.[3][21]

At-risk groups include those who:

Are aged older than 65 years (particularly patients older than 75 years or who are very frail)[3][9][21][36][52]

Have indwelling lines or catheters[3]

Have recently had surgery (in the previous 6 weeks)[3]

Are undergoing haemodialysis[36]

Have diabetes mellitus[36]

Misuse drugs intravenously[3]

Are pregnant, have given birth, or have had a termination or miscarriage in the past 6 weeks[3]

Have a breach of skin integrity (e.g., cuts, burns, blisters, skin infections).[3]

Age younger than 1 year is also a strong risk factor.[3] See Sepsis in children.

Sepsis may also be signalled by a deterioration in functional ability (e.g., a patient newly unable to stand from sitting).[3]

Be aware that any patient with known infection, with symptoms or signs of infection, or who is at high risk of infection might also have or develop sepsis, even with a NEWS2 score of less than 5.[3] In this group, continue to be aware of the risk of sepsis and specifically look for indicators that suggest the possibility of underlying sepsis:[3][41]

A single NEWS parameter of 3 or more

Non-blanching petechial or purpuric rash/mottled/ashen/cyanotic skin

Responds only to voice or pain, or unresponsive

Not passed urine in last 18 hours or urine output <0.5 mL/kg/hour

Lactate ≥2 mmol/L (≥18 mg/dL).

If a single parameter contributes 3 points to a patient’s NEWS2 score, request a high-priority review by a clinician with core competencies in the care of acutely ill patients (in the UK, FY2 or above), for a definite decision on the person's level of risk of severe illness or death from sepsis.[3] A single parameter contributing 3 points to a NEWS2 score is an important red flag suggesting an increased risk of organ dysfunction and further deterioration.[3] Clinical judgement is required to evaluate whether the patient’s condition needs to be managed as per a higher risk level than that suggested by their NEWS2 score alone. A patient’s risk level should be re-evaluated each time new observations are made or when there is deterioration or an unexpected change.[3]

Protocolised approaches

Your institution may use a guideline-based care bundle as an aide-memoire to ensure key investigations, and subsequent interventions, are carried out in a timely way as appropriate for the individual patient. Check local guidelines for the recommended approach in your area. Examples include the following.

The Sepsis Six resuscitation bundle from the UK Sepsis Trust[47]

Sepsis Six is a practical checklist of interventions that must be completed within 1 hour of identifying a patient with suspected sepsis with a NEWS2 score of 7 or more or other features of critical illness (lactate >2 mmol/L (>18 mg/dL); chemotherapy in last 6 weeks; other organ failure evident [e.g., acute kidney injury]; patient looks extremely unwell; patient is actively deteriorating).[45][47] The original paper outlining this approach, published in 2011, remains the only published evidence on Sepsis Six, and was subsequently contested.[56][57] The six interventions are:[47]

Inform a senior clinician

Give oxygen if required

Obtain intravenous access/take blood cultures

Give intravenous antibiotics

Give intravenous fluids

Monitor.

In 2022, the criteria for triggering the Sepsis Six bundle were aligned with UK Academy of Medical Royal Colleges (AOMRC) guidance and in 2024 the bundle was updated to reflect updates to NICE guidance.[3][45][47]

The 2018 hour-1 care bundle from the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC)[46]

The SSC proposes a 1-hour care bundle, based on the premise that the temporal nature of sepsis means benefit from even more rapid identification and intervention. The SSC identifies the start of the bundle as patient arrival at triage. It draws out five investigations and interventions to be initiated within the first hour:[46]

Measure lactate level and remeasure if the initial lactate level is greater than 2 mmol/L (18 mg/dL)

Obtain blood cultures before administration of antibiotics

Administer broad-spectrum antibiotics

Begin rapid administration of crystalloid at 30 mL/kg for hypotension or lactate level greater than or equal to 4 mmol/L (36 mg/dL)

Start vasopressors if the patient is hypotensive during or after fluid resuscitation to maintain mean arterial pressure level greater than or equal to 65 mmHg.

Subsequent guidance from the SSC and the UK AOMRC supports a more nuanced approach to investigating and treating patients with suspected sepsis presenting with less severe illness (e.g., without septic shock, or NEWS2 score less than 7).[43][45] Although early identification and prompt, tailored treatment are key to the successful management of sepsis, none of the published protocolised approaches is supported by evidence.[58][59] Therefore, your clinical judgement is a key part of any approach.[3][41]

Oxygen saturation in suspected sepsis

Difficulty obtaining peripheral oxygen saturations may be a red flag for shock.[3]

Peripheral oxygen saturations can be difficult to measure in a patient with sepsis if the tissues are hypoperfused.

You should have a high index of suspicion for shock if you are unable to measure oxygen saturations.

Objective evidence of new altered mental state

Determine the patient’s baseline mental state and establish whether there has been a change.[3] Use a validated scale (e.g., the Glasgow Coma Scale or AVPU ['Alert, responds to Voice, responds to Pain, Unresponsive'] scale). [ Glasgow Coma Scale Opens in new window ] [3] As well as checking response to cues, you should ask a relative or carer (if available) about the patient’s recent behaviour.[3]

Change in mental state can manifest in many ways, which makes it challenging to recognise as part of a short clinical consultation.

This is even more challenging in older patients, who may also have dementia.

Sepsis is present in many hospitalisations that culminate in death. In 2015, 23,135 people in the UK died from sepsis, where sepsis was an underlying or contributory cause of death. NHS England: Sepsis Opens in new window The true contribution of sepsis to these deaths is unknown. Most underlying causes of death in people with sepsis are thought to relate to severe chronic comorbidities and frailty.[5][7][8]

Sepsis is defined as life-threatening organ dysfunction that results from a systemic and dysregulated response to an infection.[1] The presentation can range from non-specific or non-localised symptoms (e.g., feeling unwell with a normal temperature) through to multi-organ dysfunction and septic shock.[3][21]

Septic shock is a subtype of sepsis in which the patient has persistent hypotension and a serum lactate >2 mmol/L (>18 mg/dL) despite adequate fluid resuscitation, with a need for vasopressors to maintain mean arterial pressure ≥65 mmHg.[1]

See Shock.

Early recognition of suspected sepsis is key to improving outcomes.[3][43] By the time the diagnosis becomes obvious, with multiple abnormal physiological parameters, risk of mortality is very high.[41]

Have a low threshold for suspecting sepsis: consider the possibility in any acutely unwell patient who meets both of the following criteria.

Has signs or symptoms suggesting infection. In practice, any signs of infection at presentation may be very subtle and non-specific, so easy to miss. Your initial assessment is therefore key.

Has vital observations that indicate a risk of deterioration due to organ dysfunction. Use your clinical judgement alongside a validated early warning score or a structured risk stratification process to assess this.

In hospital, use the National Early Warning Score 2 (NEWS2) or an alternative early warning score.[41][42][44] NEWS2 is endorsed by NHS England and NICE.[3][41] NEWS2 is also recommended for use in acute mental health settings and ambulances.[3]

NICE recommends to use NICE high-risk criteria for stratification of risk (rather than NEWS2) in an acute setting in patients who are or have recently been pregnant.[3]

In the community and in custodial settings, use an early warning score such as NEWS2, which is recommended by NHS England, or the NICE high-risk criteria.[3][41]

Check local guidance for your institution’s recommended approach.

See Risk stratification below.

Practical tip

Be aware that patients might not necessarily appear seriously ill at presentation, but their condition may deteriorate rapidly. The seriousness of a sepsis presentation can be easily underestimated in a busy environment, such as the emergency department.

Careful clinical assessment with a thorough history, examination, and investigations can help you identify sepsis early. You should consider the possibility of sepsis (i.e., new onset organ dysfunction) whenever an acutely ill patient presents with a suspected infection.[3]

Presentation

Always interpret signs and symptoms of sepsis in the context of the wider clinical picture as they are often non-specific and extremely variable.[21][43] Your initial assessment should focus on:

Identifying abnormalities of behaviour, circulation, or respiration: in particular, any signs suggestive of septic shock or serious organ dysfunction

and

Determining the most likely source of infection and any need for immediate source control.

Common non-specific signs and symptoms include:[21][43]

Those associated with a specific source of infection. Signs and symptoms of possible infection sources Opens in new window The most common sources are:[61]

Respiratory tract (cough/pleuritic chest pain)

Urinary tract (flank pain/dysuria)

Abdominal/upper gastrointestinaI tract (abdominal pain)

Skin/soft tissue (abscess/wound/catheter site)

Surgical site or line/drain site

Tachypnoea

High (>38°C [>100.4°F]) or low (<36°C [<96.8°F]) temperature, sometimes with rigors

Tachycardia

Acutely altered mental status

Low oxygen saturation

Hypotension

Decreased urine output

Ask the patient when they last passed urine

Poor capillary refill, mottling of the skin, or ashen appearance

Cyanosis

Malaise/lethargy

Nausea/vomiting/diarrhoea

Purpura fulminans (a very late sign but may be seen on presentation)

Ileus

Jaundice.

Practical tip

Jaundice is a rare sign of sepsis unless it is associated with a specific source of infection (biliary sepsis).

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Capillary refill time. Top image: normal skin tone; middle image: pressure applied for 5 seconds; bottom image: time to hyperaemia measuredFrom the collection of Ron Daniels, MB, ChB, FRCA; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Severe purpura fulminans; classically associated with meningococcal sepsis but can occur with pneumococcal sepsisFrom the collection of Ron Daniels, MB, ChB, FRCA; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Severe purpura fulminans; classically associated with meningococcal sepsis but can occur with pneumococcal sepsisFrom the collection of Ron Daniels, MB, ChB, FRCA; used with permission [Citation ends].

History

Take a detailed history, focusing on symptoms, recent surgery, underlying disease, history of recent antibiotic use, other medication history, and travel. Assess patients who might have sepsis with extra care if they cannot give a good history, for example people with English as a second language or people with communication difficulties (such as learning disabilities or autism).[3] Use the history to identify factors for acquiring infection and clues to infection sites to guide choice of antimicrobial therapy.[21]

Ask specific questions, including:

When was the last time you passed urine?

And how often over the past 18 hours?[3]

Do you take any medication?

Have you recently taken antibiotics?

Have you recently seen your general practitioner (GP) or been in hospital and/or had surgical procedures?

Have you travelled abroad recently?

Have you had contact with animals?

Have you had any contact with anyone infectious?

Ask about the patient’s lifestyle, including:

Drug misuse

Alcohol intake

Housing situation.

Practical tip

Check to see whether there are any microbiological samples already in the lab (e.g., urine sent by the GP) or other available test results (bloods, x-rays, etc).

Have a higher index of suspicion for sepsis when a patient presents with signs of infection and acute illness and falls into an at-risk group:

Age older than 65 years (and particularly older than 75 years)[3][9][36][52]

Immunocompromised (e.g., chemotherapy, sickle cell disease, AIDS, splenectomy, long-term steroids)[3][36][37][53][54]

Suspect neutropenic sepsis in patients who have become unwell and (a) are having or have had systemic anticancer treatment within the last 30 days or (b) are receiving or have received immunosuppressant treatment for reasons unrelated to cancer.[3]

Indwelling lines or catheters[3]

Recent surgery (in the previous 6 weeks).[3] The risk of sepsis is particularly high following oesophageal, pancreatic, or elective gastric surgery[38]

Haemodialysis[36]

Diabetes mellitus[36]

Intravenous drug misuse[3]

Pregnancy (and the 6 weeks after delivery/termination/miscarriage)[3]

Breaches of skin integrity (e.g., burns, cuts, blisters, skin infections).[3]

Age younger than 1 year is also a strong risk factor.[3] See Sepsis in children.

Practical tip

Pay particular attention to the patient’s family/carers when taking a history. They will know the patient well and might be able to offer insight into acute behavioural changes as well as changes to their respiration or circulation, compared with the norm. Consider how they may describe the result of changes in physiology that are likely to have affected the patient’s vital observations, for example:[62]

Altered mental state – ‘confused’, ‘drowsy’, ‘not themselves

Fever – ‘warm to touch’, ‘shivery’, ‘burning up

Hypotension – ‘dizzy’, ‘faint’, ‘lightheaded’

Tachypnoeic – ‘out of breath’, ‘breathless’

Tachycardic – ‘heart is racing’, ‘heart is pounding’.

Be aware of the risk of sepsis in women who are pregnant, have given birth, or have had a termination or miscarriage in the past 6 weeks. Risk factors for the development of sepsis in these groups include:[3][63]

Obesity

Gestational diabetes or diabetes mellitus

Impaired immune systems (due to illness or drugs)

Anaemia

History of pelvic infection

History of group B streptococcal infection

Amniocentesis and other invasive procedures (e.g., instrumental delivery, caesarean section, removal or retained products of conception)

Cervical cerclage

Prolonged rupture of membranes

Vaginal trauma

Wound haematoma

Close contact with people with group A streptococcal infection (e.g., scarlet fever).

Practical tip

When weighing up whether a patient who is acutely ill with symptoms or signs of possible infection can be safely managed in the community, it is important to consider whether they fall into one or more of the at-risk groups.[3]

Examination

Follow the Airway, Breathing, Circulation, Disability, Exposure (ABCDE) format to include assessment of the airway, respiratory, and circulatory sufficiency. Monitor:

Oxygen saturation

May show signs of hypoxaemia.

Respiratory rate

Heart rate

Blood pressure

Temperature

Hourly fluid balance (including urine output)

Level of consciousness (Glasgow Coma Scale or AVPU ['Alert, responds to Voice, responds to Pain, Unresponsive'] scale).

Practical tip

Difficulty obtaining peripheral oxygen saturations may be a red flag for possible shock.[3]

Peripheral oxygen saturations can be difficult to measure in a patient with sepsis if the tissues are hypoperfused.

This may occur in the later stages of the condition, as earlier in the disease process the circulation is usually hyperdynamic.

Some conditions such as meningococcal sepsis can present early with poor peripheral perfusion. These patients often have profound myocardial depression on presentation. In others, there may be a hyperdynamic central circulation concurrent with poor peripheral perfusion and a subsequent uncoupling of blood flow.

You should have a high index of suspicion for shock if you are unable to measure oxygen saturations.

See Shock.

Practical tip

Never rule out sepsis on the basis of a normal temperature reading. Fever is a common presenting sign but some patients are apyrexial or have hypothermia.[3]

Always assess the patient’s temperature in the context of their wider clinical picture.

Hypothermia at presentation is associated with a poorer prognosis than fever.[64]

People who are older (>75 years) or very frail (regardless of age) are particularly prone to a blunted febrile response and may present with a normal temperature.[3][65]

Patients with a spinal cord injury may not develop a raised temperature.[3]

Other groups that are less susceptible to temperature fluctuations and so may not develop a raised temperature with sepsis include:[3]

Infants or children

People with cancer receiving treatment

Severely ill patients.

Practical tip

Always interpret the vital signs that you take as part of the ABCDE assessment in relation to the patient’s known or likely baseline for that parameter; take account of the patient in front of you and the full clinical picture. For example:

A fall in systolic blood pressure of ≥40 mmHg from the patient’s baseline is a cause for concern, regardless of the systolic blood pressure reading itself[3]

Although tachycardia can be an indicator of potential risk of sepsis developing, when assessing heart rate you should consider:[3]

Pregnancy

In pregnant women, heart rate is usually 10 to 15 bpm faster than normal

Older people

Older people may not develop tachycardia in response to infection and are more at risk of developing new arrhythmias (e.g., atrial fibrillation)

Medications

Some drugs, such as beta-blockers or rate-limiting calcium-channel blockers, may inhibit a tachycardic response to infection

Baseline

The baseline heart rate in young people or people who are very physically fit (e.g., athletes) may be lower than the norm. The rate of change of heart rate may therefore be more important (to reflect the severity of infection) than the actual rate.

Pay particular attention to common signs and symptoms:[3][43]

Of possible organ dysfunction

Cyanosis of the skin, lips, or tongue

Jaundice

Oliguria

Mental status changes

Airway compromise, dyspnoea, hypoxaemia, fever, or hypothermia

Purpura fulminans

Fever or hypothermia

Arrhythmia

Tachypnoea

Of possible shock[66]

Hypotension

Arrhythmia

Skin changes (mottled, ashen, sweaty; cold or clammy peripheries)

Fever or hypothermia

Oliguria

Of possible circulatory insufficiency

Oliguria

Mottled, ashen appearance; sweating

Prolonged capillary refill times

Of possible hypovolaemia[67]

Reduced peripheral skin perfusion and skin temperature

Reduced skin turgor and dry mucous membranes

Postural hypotension

Thirst

Indicating potential infection/source of infection. Signs and symptoms of possible infection sources Opens in new window Most commonly:[20][61]

Respiratory tract (cough/pleuritic chest pain/tachypnoea/dyspnoea)

Urinary tract (suprapubic tenderness, loin tenderness, dysuria)

Abdominal/upper gastrointestinal tract (abdominal pain or guarding/decreased bowel sounds/diarrhoea/vomiting)

Skin/soft tissue (breakdown of abscess/wound with redness, swelling, or discharge)

Post-operative (redness/swelling/discharge/pain at surgical site or line/drain site).

Practical tip

Change in mental state is a commonly missed sign of sepsis, particularly in older patients in whom dementia may co-exist. Change in mental state is often due to non-infectious causes (e.g., electrolyte disturbances). It can manifest in many ways, which makes it challenging to recognise as part of a short clinical consultation.

The term ‘confusion’ can be unhelpful and instead you should attempt to identify any change from the patient’s normal behaviour or cognitive state.[3]

A collateral history – if friends, family members, or carers are available – is key. They might describe the patient as ‘not themselves’.

In people with dementia or learning disability, change in mental state may present as irritability or aggression, but in dementia could also present with hypoactive delirium (e.g., with lethargy, apathy).[3][60]

In addition, sepsis may be signalled by a deterioration in functional ability (e.g., a patient newly unable to stand from sitting).[3]

Ensure any patient with suspected sepsis has frequent and ongoing monitoring (e.g., using an early warning score such as the National Early Warning Score 2 [NEWS2]).[3] For advice on when to consult a senior colleague or escalate to critical care see Management recommendations.

Early identification of sepsis relies on systematic assessment of any acutely ill patient who presents with presumed infection to identify their risk of deterioration due to sepsis. By the time sepsis is at an advanced stage, with multiple abnormal physiological parameters, the risk of mortality is very high.[41]

In any patient in whom sepsis is a possibility, use a systematic process to check vital observations and assess and record the risk of deterioration.[41][42][43] Remember that no risk stratification process is 100% sensitive or 100% specific; therefore, you must use your clinical judgement.

Consult local guidelines for the recommended approach for assessing acute deterioration.

In hospital: use the National Early Warning Score 2 (NEWS2) or an alternative early warning score.[41][42][44] NEWS2 is endorsed by NHS England and NICE for use in this setting.[3][41] NEWS2 is also recommended for use in acute mental health settings and ambulances.[3]

NICE recommends to use the NICE high-risk criteria for stratification of risk (rather than NEWS2) in an acute setting in patients who are or have recently been pregnant.[3]

In the community and in custodial settings: use an early warning score such as NEWS2, which is recommended by NHS England and supported by the Royal College of General Practitioners in the UK.[41][51] An alternative in the UK is to use the NICE high-risk criteria.[3]

None is validated in primary care.[51]

NEWS2 is the most widely used early warning score in the UK National Health Service and is endorsed by NHS England and NICE).[3][41] NHS England: Sepsis Opens in new window In a patient with a known or likely infection, a NEWS2 score of 5 or more is likely to indicate sepsis.[42]

In hospital: use the NEWS2 early warning score together with your clinical judgement

Early warning scores are often used in hospitals to triage patients and to detect clinical deterioration or improvement over time.[68][69] NEWS2 is the latest version of the National Early Warning Score (NEWS), first developed by the UK Royal College of Physicians in 2012 and updated in 2017.[41][42][44]

NEWS has been tested and validated in many different healthcare settings, including emergency departments and pre-hospital care, and has performed well.[3][42]

NHS England and NICE recommend NEWS2 for risk stratification and early identification of sepsis in any acutely ill patient who has symptoms or signs of infection.[3][41]

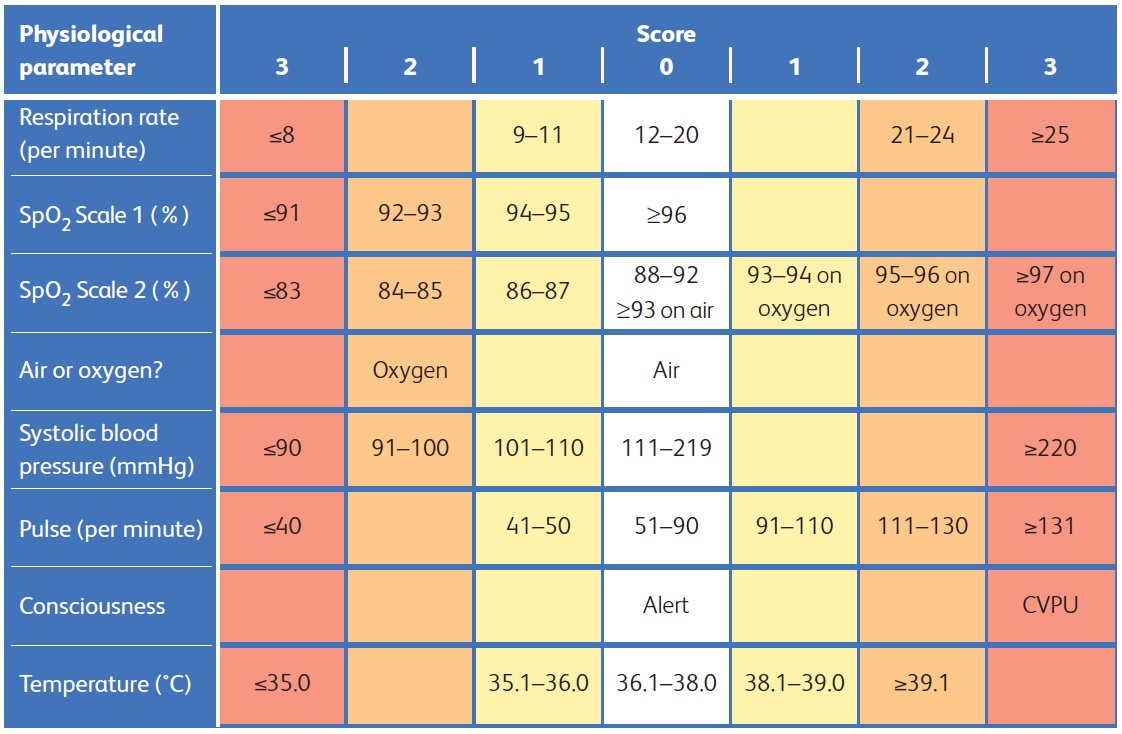

NEWS2 is based on the assessment of six individual parameters, which are each assigned a score of between 0 and 3:[41][42][44]

Respiratory rate

Oxygen saturations

There are different scales for oxygen saturation levels based on a patient’s physiological target; use scale 2 for patients at risk of hypercapnic respiratory failure

Temperature

Blood pressure

Heart rate

Level of consciousness.

Assess each parameter individually and then add up the final score.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: National Early Warning Score 2 (NEWS2) is an early warning score produced by the Royal College of Physicians in the UK. It is based on the assessment of six individual parameters, which are assigned a score of between 0 and 3: respiratory rate, oxygen saturations, temperature, blood pressure, heart rate, and level of consciousness. There are different scales for oxygen saturation levels based on a patient’s physiological target (with scale 2 being used for patients at risk of hypercapnic respiratory failure). The score is then aggregated to give a final total score; the higher the score, the higher the risk of clinical deteriorationReproduced from: Royal College of Physicians. National Early Warning Score (NEWS) 2: Standardising the assessment of acute-illness severity in the NHS. Updated report of a working party. London: RCP, 2017. [Citation ends].

In an acutely ill patient with symptoms or signs of infection, the NEWS2 score can be an indicator of the likelihood of sepsis.[3] The higher the resulting aggregate score, the higher the risk of clinical deterioration.[41][42] Use the following approach as a guide alongside your clinical judgement, based on the individual patient, their history, and their prognosis.[3]

NEWS2 aggregate score in a patient with possible, probable, or definite infection | Why? | |

≥7 |

| Very likely to be sepsis; significant risk of mortality |

≥5 |

| Likely to be sepsis |

<5 |

If a single parameter contributes 3 points to a patient’s NEWS2 score, request a high-priority review by a clinician with core competencies in the care of acutely ill patients (in the UK, FY2 or above), for a definite decision on the person's level of risk of severe illness or death from sepsis.[3] | May be sepsis |

Practical tip

Interpret the initial NEWS2 score in the context of your clinical assessment. Assess patients who might have sepsis with extra care if they cannot give a good history, for example, people with English as a second language or people with communication difficulties (such as learning disabilities or autism).[3] Upgrade the patient’s severity status and your accompanying actions to at least the next NEWS2 level if there is clinical or carer concern, continuing deterioration or lack of improvement, surgically remediable sepsis, neutropenia, or blood gas/laboratory evidence of organ dysfunction (including elevated serum lactate).[3][45] Interpretation should take into account any NEWS2 score calculated (or intervention carried out) before initial assessment in the accident and emergency department.[3] A patient’s risk level should be re-evaluated each time new observations are made or when there is deterioration or an unexpected change.[3]

Debate: Role of the qSOFA score

Although the sequential organ failure assessment score (SOFA) and quick-SOFA (qSOFA) are accepted as useful tools for prognostication, they are not recommended by UK or international guidelines as a tool for early identification of sepsis.

NHS England and NICE recommend the use of NEWS2 scores in the acute setting. NICE recommends its own risk stratification criteria in community and custodial settings, and in an acute setting in patients who are or have recently been pregnant.[3][41][70] NHS England: Sepsis Opens in new window

The Surviving Sepsis Campaign advises against using the qSOFA score compared with NEWS or the Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS) as a single screening tool for sepsis or septic shock.[43]

While the qSOFA score is not a bedside scoring tool, it can be used as an alternative to NEWS to identify any patient at high risk of an adverse outcome in healthcare systems that don’t use NEWS. qSOFA shares 3 of the 7 NEWS2 criteria; using qSOFA, an acutely ill patient with suspected or confirmed infection is considered to be at high risk of an adverse outcome (from sepsis) if at least two of the following three criteria are present:[1]

Altered mental state (Glasgow Coma Scale score <15)

Systolic blood pressure ≤100 mmHg

Respiratory rate ≥22 breaths/minute.

Evidence suggests that early warning scores such as NEWS2 have better sensitivity and specificity than the qSOFA score for predicting deterioration and mortality among patients presenting to the emergency department with suspected infection.[69]

Practical tip

It is important to be aware that no scoring system has been validated for use in pregnant women or women who have recently been pregnant (in the 24 hours following a termination of pregnancy or miscarriage for 4 weeks after giving birth); in practice, seek senior input to determine the best approach in these patients.

The UK NICE recommends use of the NICE high-risk criteria for stratification of risk (rather than NEWS2) in an acute setting in patients who are or have recently been pregnant.[3]

Examples of scores that have been developed but are yet to be universally accepted include the following.

A modified qSOFA has been proposed by the Society of Obstetric Medicine Australia and New Zealand (SOMANZ) for use in pregnant women. The SOMANZ score includes systolic blood pressure 90 mmHg, respiratory rate >25 per minute, and altered mental status.[71]

The Sepsis in Obstetrics Score uses a combination of maternal temperature, blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, peripheral oxygen saturation, white blood cell count, and lactic acid level as predictors of intensive care admission for sepsis.[72]

Ensure there is senior input, with a low threshold to escalate to a consultant, if a patient with suspected sepsis who is or has recently been pregnant and meets any high-risk criteria, does not respond within 1 hour of any intervention.[3]

In the community: use the NEWS2 early warning score or the NICE high-risk criteria, together with your clinical judgement

Primary care has a significant role to play in identifying suspected sepsis at an early stage and to promptly escalate care where appropriate.[51] A key aspect of this is the consistent use and recording of physiology as part of the assessment of infection and the deteriorating patient. The method selected for doing this in primary care is still open to challenge due to a lack of evidence in this setting; no one approach to risk stratification has been validated in primary care.[51] Therefore, using your clinical judgement in making a decision is paramount.[41]

To identify which acutely ill patients with suspected or confirmed infection are at high risk of deterioration due to sepsis in the community, use either:

NEWS2 or an alternative early warning score[41][42][51] NHS England: Sepsis Opens in new window

NEWS2 is recommended by NHS England and supported by the Royal College of General Practitioners in the UK and NICE.[3][41][51]

-or-

The NICE sepsis high-risk criteria[3]

NICE recommends to use these criteria for stratification of risk in people aged 16 or above if they are in community or custodial settings or if they are in an acute setting and are, or have recently been, pregnant.[3]

If an acutely ill patient presents with symptoms and signs of infection AND meets any one or more of these criteria, OR is deemed to be at risk of neutropenic sepsis, refer for emergency medical care in hospital (usually by blue-light ambulance in the UK):

Objective evidence of new altered mental state (e.g., new deterioration in Glasgow Coma Scale score/AVPU ['Alert, responds to Voice, responds to Pain, Unresponsive'] scale)

Respiratory rate: 25 breaths per minute or more OR new need for oxygen (40% or more fraction of inspired oxygen [FiO2]) to maintain saturation more than 92% (or more than 88% in known chronic obstructive pulmonary disease)

Heart rate: more than 130 beats per minute

Systolic blood pressure 90 mmHg or less or systolic blood pressure more than 40 mmHg below normal

Not passed urine in previous 18 hours, or for catheterised patients passed less than 0.5 mL/kg of urine per hour

Mottled or ashen appearance

Cyanosis of skin, lips, or tongue

Non-blanching petechial or purpuric rash on skin.

Historically, respiratory rate, blood pressure/perfusion, and cognition are among the least well recorded values by general practitioners in the UK when assessing patients with sepsis.[61]

Note that NICE recommends to use NEWS2 (rather than the NICE sepsis high-risk criteria) in ambulances.[3]

Practical tip

A systematic approach is key to earlier identification of patients at risk of sepsis. The Royal College of General Practitioners in the UK highlights the importance of ensuring you have the right equipment available in every consultation room, including: a thermometer (tympanic and axillary), a pulse oximeter suitable for use in all age groups, and a sphygmomanometer.[73]

Take a cautious approach when deciding whether it is safe to treat an acutely unwell patient in the community.

For more details on managing patients in the community, see Management recommendations.

Practical tip

If you need to refer a patient for emergency medical care in hospital, it is important to inform the hospital clinical team that the patient is on the way. This will enable the hospital to prepare to start appropriate management as soon as the patient arrives.

Make intensive efforts to identify the most likely anatomical source of infection as soon as possible, including sources that might need drainage or other interventions.[3][43] Consider the need for urgent source control as soon as the patient is stable.

Start with a thorough and focused clinical history and examination, as well as initial investigations including imaging.[3]

Early and adequate source control is critical, particularly for:[43]

Gastrointestinal sources (such as visceral abscesses, cholangitis, or peritonitis secondary to perforation)

Severe skin infections (e.g., necrotising fasciitis)

Infection involving an indwelling device, where a procedure or surgery is likely to be required.

Consider all lines, including Hickman and peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC), and catheters as potential sources. If you suspect a line infection, is it good practice to remove the line and culture the tip.[43]

Assume that any intravenous route is likely to either be the source of the infection, or will seed infections in the bloodstream, making eradication particularly difficult. Therefore, the priority for source control is often to remove any intravenous devices after vascular access has been obtained.[43]

Involve the relevant surgical team early on if surgical or radiological intervention is suitable for the source of infection.[3][45] The surgical team or interventional radiologist should seek senior advice about the timing of intervention and carry the intervention out as soon as possible, in line with the advice received.[3]

In practice, this may mean early transfer of the patient to a surgical centre if there are no facilities at your hospital.

Sites of infection

The respiratory tract is the most common site of infection in people with sepsis, followed by the abdomen, urinary tract, soft tissues, and joints, and – rarely – the central nervous system.[20]

Beware necrotising fasciitis and septic arthritis, which require immediate surgical intervention.

Practical tip

Necrotising fasciitis is notoriously difficult to diagnose. The initial symptoms are non-specific and the clinical course is often slower than might be expected. Typically, the first sign is pain disproportionate to the clinical findings, followed or accompanied by fever.[74]

Evidence: Infectious causes of sepsis

The Extended Prevalence of Infection in Intensive Care (EPIC II) study provides the best recent evidence on the infectious causes of sepsis in an intensive care setting.[20]

The study gathered extensive data from more than 14,000 adult patients in 1265 intensive care units from 75 countries on a single day in May 2007.

Of the 7000 patients classified as ‘infected’, the sites of infection were the:

Lungs: 64%

Abdomen: 20%

Bloodstream: 15%

Renal or genitourinary tract: 14%.

Of the 70% of infected patients with positive microbiology:

47% of isolates were gram-positive ( Staphylococcus aureus alone accounted for 20%)

62% were gram-negative (20% Pseudomonas species and 16% Escherichia coli)

19% were fungal.

Other studies tend to broadly concur on the relative frequencies of sources of infection. The graph below shows the results of the National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death (NCEPOD) report in 2015.[61]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: The relative frequencies of sources of infection in sepsisCreated by the BMJ Knowledge Centre; based on 'NCEPOD. Just say sepsis! Nov 2015' [Citation ends]. Evidence from studies in people over age 65 years shows the genitourinary tract is the biggest source of infection.[21][22]

Evidence from studies in people over age 65 years shows the genitourinary tract is the biggest source of infection.[21][22]

Start treatment promptly and before test results are available if the patient is critically ill (e.g., septic shock or NEWS2 score 7 or more).[45]

Above all else, if the patient has suspected sepsis, always:[3][46][47]

Take two sets of blood cultures

Measure serum lactate

Start monitoring hourly urine output.

Complete these investigations within 1 hour for patients with a NEWS2 score of 7 or more calculated on initial assessment in the accident and emergency department or on ward deterioration, or within 3 hours for patients with a NEWS2 score of 5 or 6.[3][45]

Take bloods immediately, before antibiotics are started (although sampling should not delay the administration of antibiotics).[3][43][48][49]

Practical tip

Take blood cultures and measure serum lactate at the same time.

Practical tip

Recommended timeframes are not intended to permit delay in treatment, but to offer time to make a safe and informed clinical decision. If actions can be completed earlier than the proposed time limit, then they should be.[45]

Blood cultures

Ideally, take peripheral blood cultures (aerobic and anaerobic) from at least two different sites.[46]

Prioritise filling the aerobic bottle before filling the anaerobic one.

To improve yield, ensure these samples are incubated as soon as possible.

If you suspect a line infection, remove the line and culture the tip.

Practical tip

Take cultures of blood and other fluids at the first opportunity as they may take up to 48 to 72 hours to yield sensitivities of causative organisms (if identified). It is usually possible to take cultures first without this causing any delay to administration of antibiotics. This is important as cultures are far less likely to be positive if delayed until after giving antimicrobials.

Lactate

Measure serum lactate, on a blood gas, to determine the severity of the sepsis and monitor response to treatment.[3][46][47]

Lactate is a marker of stress and may be a marker of a worse prognosis (as a reflection of the degree of stress). Raised serum lactate highlights the possibility of tissue hypoperfusion and may be present in many conditions.[75][76]

Lactate may normalise quickly after fluid resuscitation. Patients whose lactate levels fail to normalise after adequate fluids are the group that fare worst.

Lactate >4 mmoL/L (>36 mg/dL) is associated with worse outcomes.

One study found in-hospital mortality rates as follows:[77]

Lactate <2 mmol/L (<18 mg/dL): 15%

Lactate 2.1 to 3.9 mmol/L (19 to 35mg/dL): 25%

Lactate >4 mmol/L (>36 mg/dL): 38%.

Do not be falsely reassured by a normal lactate (<2 mmol/L [<18 mg/dL]).

This does not rule out the patient being acutely unwell or at risk of deterioration or death due to organ dysfunction. Lactate helps to provide an overall picture of a patient's prognosis but you must take into account the full clinical picture of the individual patient in front of you including their National Early Warning Score 2 (NEWS2) score to determine when/whether to escalate treatment.[3]

Practical tip

Lactate is typically measured using a blood gas analyser, although laboratory analysis can also be performed.

Traditionally, arterial blood gas has been recommended as the ideal means of measuring lactate accurately. However, in practice, in the emergency department setting it may be more practical and quicker to use venous blood gas, which is recommended by NICE although this recommendation is not supported by strong evidence.[3] Evidence suggests good agreement at lactate levels <2 mmol/L (<18 mg/dL) with small disparities at higher lactate levels.[78][79][80]

Be aware that persisting raised lactate may not be recognised until after initial resuscitation has been given. In the patient with persisting raised lactate, ensure:

Adequate source control; remove any suspected septic or necrotic focus

The patient is adequately filled (their central venous pressure 'goes up and stays up')

The patient’s cardiac output and blood pressure are adequate for their tissue needs (a low central venous oxygen saturation, ScvO 2, serves as a good indicator of impaired tissue oxygenation).

Practical tip

Persistent raised lactate should incite efforts to identify other hidden causes including thiamine deficiency, adrenaline or other drugs, and liver failure.

Urine output

Assess the patient’s urine output.[3][47]

Ask the patient or their carer about urine output over the previous 12 to 18 hours

Consider catheterising the patient on presentation if they are shocked, confused, oliguric, or critically unwell

Ensure arrangements are in place for urine output to be monitored once an hour.

A low urine output may suggest intravascular volume depletion and/or acute kidney injury and is therefore a marker of sepsis severity.[3]

A patient who has not passed urine in the previous 18 hours (or for catheterised patients passed less than 0.5 mL/kg of urine per hour) is at high risk of severe illness or death from sepsis.[3]

Care bundles

Your institution may use a guideline-based care bundle as an aide-memoire to ensure key investigations, and subsequent interventions, are carried out in a timely way as appropriate for the individual patient. Check local guidelines for the recommended approach in your area. Examples include the following.

The Sepsis Six resuscitation bundle from the UK Sepsis Trust[47]

Sepsis Six is a practical checklist of interventions that must be completed as quickly as possible, and for the sickest patients always within 1 hour of identifying suspected sepsis.[47] The original paper outlining this approach, published in 2011, remains the only published evidence on Sepsis Six, and was subsequently contested.[56][57] The six interventions are:[47]

Inform a senior clinician

Give oxygen if required

Obtain intravenous access/take blood cultures

Give intravenous antibiotics

Give intravenous fluids

Monitor.

The 2018 hour-1 bundle from the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC)[46]

The SSC proposes a 1-hour care bundle, based on the premise that the temporal nature of sepsis means benefit from even more rapid identification and intervention. The SSC identifies the start of the bundle as patient arrival at triage. It draws out five investigations and interventions to be initiated within the first hour:[46]

Measure lactate level and remeasure if the initial lactate level is greater than 2 mmol/L (18 mg/dL)

Obtain blood cultures before administration of antibiotics

Administer broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics

Begin rapid administration of crystalloid at 30 mL/kg for hypotension or lactate level greater than or equal to 4 mmol/L (36 mg/dL)

Start vasopressors if the patient is hypotensive during or after fluid resuscitation to maintain mean arterial pressure level greater than or equal to 65 mmHg.

Subsequent guidance from the SSC and the UK Academy of Medical Royal Colleges supports a more nuanced approach to investigating and treating patients with suspected sepsis presenting with less severe illness (e.g., without septic shock, or NEWS2 score less than 7).[43][45] Although early identification and prompt, tailored treatment are key to the successful management of sepsis, none of the published protocolised approaches is supported by evidence.[58][59] Therefore, your clinical judgement is a key part of any approach.

Controversy: Protocolised care bundles

Robust evidence to support the use of care bundles, such as Sepsis Six or the SSC hour-1 bundle (2018), to improve outcomes in people with sepsis is lacking.[58][59]Available data are from observational studies only, which come with methodological limitations; in particular, they cannot resolve questions of causality.[56][81][82][83][84][85][86]Some organised medical societies have declined to support 1-hour target-based approaches to the management of sepsis, while other current guidelines mandate the importance of 1-hour care bundles.[3][58][59][87][88][43]There is agreement across the board that appropriate and timely recognition and subsequent resuscitation are important for any severely ill patient presenting with sepsis.[3][43][58][59][87][88]

Sepsis Six was specifically designed to facilitate early intervention in busy hospital and pre-hospital settings.[89][90] The original paper outlining the approach, published in 2011, was a prospective observational cohort study that looked at data from 567 patients.[56] Statistical analysis of the data did not take into account the differences between the cohorts: most importantly, age and infection source. The study reported that delivery of the bundle is associated with a 55% relative risk reduction in mortality.[56] Further evidence has since emerged to contest the delivery of Sepsis Six translating to any improvement in mortality.[57] In 2022, the Sepsis Six-recommended timeframes for investigation and treatment of patients with suspected sepsis were amended in line with UK Academy of Medical Royal Colleges (AOMRC) guidance, with a 1-hour window for patients with the highest-severity illness (e.g., septic shock or NEWS2 score 7 or more) and a 3-hour window for patients with less severe illness.[45][47] There was a subsequent update in 2024 to reflect updates to NICE guidance.[3][47]

Other datasets report clinical improvements associated with earlier completion of sepsis bundles, some citing an increased mortality for every hour’s delay.[81][82][83][84][85][86]

Commentators have challenged the methodology of these studies, which were all observational cohorts that separated patients by the time to intervention and usually after a clear start signal, such as shock or an elevated lactate level – in particular, their inability to:[58][59]

Define causation, only association

Detect the granular differences that 1 hour versus 2 or 3 hours to complete makes on overall care (for patients with and without sepsis alike).

The temporal benefits identified in these trials existed in the sickest subset of patients with septic shock, suggesting that when they are applied to a general population in the emergency department, overall benefit will be diluted and net harm (from over-treatment) may occur.[83]

Owing to these gaps in robust evidence, some organised medical societies have declined to support the care-bundle-based recommendations, citing the lack of data to support current proposed targets.[58][59]

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) has withheld its endorsement of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines and the 1-hour bundle, as has the American College of Emergency Physicians.[59] IDSA notes that 40% of patients admitted to intensive care for sepsis ultimately do not have that condition, leading to adverse consequences of unnecessary antibiotics.[87]

IDSA and others encourage the gathering of more data to confirm a diagnosis of sepsis and working to a less rigid time threshold.[88]

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK recommends 1-hour targets, as does NHS England (under specific circumstances).[3][41]

Although the SSC still promotes use of a 1-hour care bundle, the SSC 2021 guideline update recommends stratification of patients with suspected sepsis according to the presence or absence of septic shock, with initial investigation and treatment to take place within 1 hour if shock is present, or within 3 hours for patients with less severe illness.[43] This change is based largely on the evidence from a 2018 prospective randomised controlled trial evaluating early antibiotic administration in an undifferentiated cohort of patients with suspected infection that found no benefit.[91] A 2022 statement from the UK’s AMORC supports this approach.[45]

Blood tests

Full blood count

Carry out a venous blood test to determine the patient’s full blood count.[3]

Thrombocytopenia of non-haemorrhagic origin may occur in patients who are severely ill with sepsis.[92]

Persistent thrombocytopenia is associated with an increased risk of mortality.[92]

Lymphocytopenia is increasingly recognised as a useful sign in a patient with sepsis.

The white blood cell (WBC) count is neither sensitive nor specific for sepsis.[93]

WBC count was one of the diagnostic criteria for sepsis under the old systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) definition but this has been superseded by the 2016 Sepsis-3 diagnostic criteria, which rely on demonstrating organ dysfunction.[1]

Practical tip

Non-infectious (e.g., crush) injury, surgery, cancer, and immunosuppressive agents can also lead to either increased or decreased WBC counts.

Urea and electrolytes (including creatinine)

Request urea and electrolyte tests;[3] use to:

Evaluate the patient for renal dysfunction

Patients with acute kidney injury due to sepsis have a worse prognosis than those with non-septic acute kidney injury[94]

Determine whether the patient would benefit from haemofiltration or intermittent haemodialysis[43]

Identify sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium, and chloride abnormalities.

Serum glucose

Measure serum glucose on a blood gas, in venous blood through venepuncture, or via capillary blood with bedside testing.[3]

Depending on the patient’s baseline glucose level, hyperglycaemia may be associated with increased morbidity and mortality in patients with sepsis.[95]

Bear in mind that studies of people with diabetes show no clear association between hyperglycaemia during intensive care unit stay and mortality and markedly lower odds ratios of death at all levels of hyperglycaemia.[96]

Glucose levels may be elevated, with or without a known history of diabetes mellitus, due to the stress response and altered glucose metabolism.[95][97] Drug therapy (e.g., with corticosteroids and catecholamines) may also lead to elevated glucose.

C- reactive protein

Carry out a venous blood test to determine the patient’s level of C-reactive protein.[3]

Reasonably sensitive, but not specific, for sepsis.[3][101][102]

Serum procalcitonin

Baseline serum procalcitonin is increasingly being used in critical care settings to guide decisions on how long to continue antibiotic therapy.[43][103][104][105]

Procalcitonin is a peptide precursor of calcitonin, which is responsible for calcium homeostasis.

The SSC suggests using procalcitonin alongside clinical evaluation to decide when to discontinue antimicrobials.[43]

Clotting screen

Include prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and fibrinogen.[3]

Use to determine whether the patient has established coagulopathy in the presence of sepsis. This is associated with a worse prognosis.[106]

Liver function tests

Use liver function tests, notably bilirubin, to evaluate for organ dysfunction.[3][107][108] Liver dysfunction may also be a cause of a coagulopathy.

Blood gas

Request blood gas tests.[3]

Use either arterial blood gas (ABG) or venous blood gas evaluation. Use ABG to optimise oxygenation and assess metabolic status (acid-base balance), particularly with regard to the arterial carbon dioxide level (PaCO 2).

In ventilated patients, this may help to determine the positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP), while minimising adverse levels of inspiratory pressure and unnecessarily high fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO 2).

Practical tip

VBG is increasingly being used in preference to ABG in the emergency department, particularly if a respiratory cause seems unlikely. VBG is less invasive and less painful than ABG and evidence shows there is good concordance between venous and arterial values for pH, bicarbonate ion concentration, base excess, and lactate.[76] ABG will be used instead of VBG if the patient is escalated to critical care as an arterial line is usually inserted for ease of access.

Be aware that venous PCO 2 may be artificially high if taken from a tourniqueted limb.

Investigations to identify source of infection

Tailor investigations to the patient’s history and examination findings.[3]

Involve the relevant surgical team early on if surgical or radiological intervention is suitable for the source of infection.[3][45] The surgical team or interventional radiologist should seek senior advice about the timing of intervention and carry the intervention out as soon as possible, in line with the advice received.[3]

Urine analysis

Consider a dipstick test in any patient who has suspected sepsis to help add weight to a suspected urinary source of infection.[3]

Always interpret urine analysis in the context of the wider clinical assessment.

Bear in mind that this does not definitively confirm a urinary source, particularly as urine analysis has a low specificity.[109]

Chest x-ray

Consider a chest x-ray (CXR) in any patient with suspected sepsis to help add weight to a suspected respiratory source (the most common source) of infection.[3]

Cultures from multiple sources

Consider taking cultures from multiple sources to determine the site and/or organism responsible for the infection, including:[43]

Urine

Sputum (if accepted by the laboratory)

Stool

Cerebrospinal fluid

Pleural fluid

Ascitic fluid

Joint fluid

Abscess aspirate

Swabs from open wounds or ulcers.

Lumbar puncture

Perform a lumbar puncture if you suspect meningitis or encephalitis, provided there is no suspicion of raised intracranial pressure (a computed tomography scan should be performed prior to lumbar puncture if you suspect raised intracranial pressure) or other risk to performing the procedure.[3]

This should never delay treatment, particularly the administration of antibiotics.

Do not perform a lumbar puncture if any of the following contraindications are present:[3][112]

Extensive or spreading purpura

Infection at the lumbar puncture site

Risk factors for an evolving space-occupying lesion

Any of these symptoms or signs, which might indicate raised intracranial pressure:

New focal neurological features (including seizures or posturing)

Abnormal pupillary reactions

A Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 9 or less, or a progressive and sustained or rapid fall in level of consciousness.

How to perform a diagnostic lumbar puncture in adults. Includes a discussion of patient positioning, choice of needle, and measurement of opening and closing pressure.

Computed tomography

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest and/or abdomen and pelvis provides cross sectional imaging of the body to attempt to identify the source of sepsis.[3] Consider early CT if you suspect gastrointestinal infection in particular as, in practice, outcomes tend to be worse with gastrointestinal sepsis compared with other sites of infection.

A CT scan can help to identify a hidden collection (e.g., an intra-peritoneal abscess or effusion) in a patient presenting with ‘acute abdomen’, which may not be readily apparent on ultrasound or chest x-ray.

CT can also be used to identify free air (perforation).

Involve the relevant surgical team early on if surgical or radiological intervention is suitable for the source of infection.[3][45] The surgical team or interventional radiologist should seek senior advice about the timing of intervention and carry the intervention out as soon as possible, in line with the advice received.[3]

Ultrasound

Consider ultrasound scanning to help locate the source of the infection, particularly if you suspect an abdominal source or where the source of infection is not clear after the initial clinical examination and tests.[3]

In particular, use ultrasound to identify:

Abscesses in the liver or skin

Free fluid (peritonitis)

Hydronephrosis (pyelonephritis).

Ultrasound has a reasonable false negative rate; absence of positive findings on ultrasound does not rule out any given infection source.

Urine antigen testing

Carry out legionella and pneumococcal urine antigen testing in all patients with suspected or confirmed community-acquired pneumonia.[119]

Viral swabs

Consider rapid respiratory viral polymerase chain reaction in people with suspected respiratory aetiology.[120]

Other investigations for all patients

ECG

Request a baseline ECG for any patient with suspected sepsis, as you would for all acutely ill presentations, to:

Rule out differential diagnoses: for example, myocardial infarction, pericarditis, or myocarditis

Detect arrhythmias (e.g., atrial fibrillation); commonly seen in older people with sepsis.[3]

Other investigations to consider for some patients

HIV screen

Consider performing a screen for HIV infection, particularly in patients presenting with recurrent infections or atypical infections and those considered to be in high-risk groups.[121]

Key risk factors for contracting HIV infection include intravenous drug use and unprotected sexual intercourse (heterosexual and homosexual).

Echocardiogram (echo)

Consider echo for a more detailed assessment of the causes of the haemodynamic issues. Use echo to assess (left and/or right) ventricular dysfunction, which may be caused by sepsis, and to detect endocarditis. Echo can also be used to assess inferior vena cava collapsibility, which is a marker of hypovolaemia, and to guide fluid resuscitation.[43]

How to perform a diagnostic lumbar puncture in adults. Includes a discussion of patient positioning, choice of needle, and measurement of opening and closing pressure.

How to insert a tracheal tube in an adult using a laryngoscope.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer