Approach

Because signs and symptoms mimic those of other urinary disorders, and because no definitive tests exist to identify the disease, physicians must exclude other conditions before considering a diagnosis.[1][20]

Diagnosis depends on the existence of a complex of symptoms, including frequency, urgency, and bladder pain, without any other definitive cause.[11] Physicians must carefully consider all patients with chronic pelvic pain as potential interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) candidates.

Cystoscopy is the most important diagnostic test for assessing a patient with co-existing haematuria, as urothelial carcinoma can present with similar symptomatology. Urinalysis with culture and microscopy, vaginal wet prep, and thorough pelvic examination assessing the pelvic floor are useful in ruling out other diagnoses. Newer tests are emerging but are currently in the research phase.

History

The most common age range for presentation is 20 to 60 years.[11] However, cases in younger and older patients, as well as rarely in children, have been reported.[16] The diagnosis is 5 times more likely in women than in men.[11] Some studies suggest IC/BPS is more common among white people.[10][13] While not traditionally considered an inherited condition, there may be a genetic association.[17] Recent studies demonstrate that up to 68% of patients may have experienced sexual abuse. Also, 49% may experience domestic violence, and 78% may encounter physical abuse in their home and family.[18][19] Any treatments should include referral to psychological and social support services. Chronic pain and catastrophising are associated with poorer quality of life and poor response to treatment.

Patients typically present with urinary frequency, urgency, nocturia, dysuria, and pelvic pain associated with bladder filling and/or emptying. The resulting discomfort may range from abdominal suprapubic tenderness to intense pain of the pelvic floor. Urgency may lead to incontinence in some patients. Many women complain of pain/discomfort during intercourse, and some women experience a worsening of symptoms before menses. Studies have shown higher rates of vulvodynia, coccydynia, and urethral pain in these patients, which may overlap with their bladder symptoms.[21] Male patients may complain of scrotal and/or anal pain, and urethral itching. The condition is typified by exacerbations, remissions, and varying degrees of symptom severity.

A bladder diary compiled by the patient is helpful for correlating symptoms with food, and emotional or physical stress, because these factors may exacerbate symptoms.[22] A basic voiding diary should catalogue timing and volume of voids, as well as incontinence episodes and urgency/pain sensations. A patient with a maximum voided volume appropriate for age is less likely to have chronic, ulcerative IC. Some patients may present only with daytime symptoms. Patient support and advocacy groups publish diet recommendations, and patients should be questioned about any relationships between diet and symptoms. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK): your daily bladder diary Opens in new window Pain symptoms should be measured subjectively or objectively with a visual analogue scale or validated symptom scale. Interstitial Cystitis Symptom Index and Problem Index (ICSI-PI) Opens in new window

Comorbidities are common and include fibromyalgia, vulvar vestibulitis, vulvodynia, systemic lupus erythematosus, migraine, rheumatoid arthritis, allergies, and chronic fatigue syndrome.[7][23][24][25][26][27][28] Patients may also have concomitant symptomatic or asymptomatic pelvic organ prolapse, bladder malignancy, or urinary tract infection. It is imperative that the clinician be vigilant for other contributing diagnoses to avoid treatment delay for other conditions.

Physical examination

A bi-manual pelvic examination should be performed.[1] Key signs for diagnosis include pain to the anterior vaginal wall overlying the urethra and bladder neck; severe pubic pain when the body of the bladder is examined; and pain on palpation of the vaginal pelvic side walls onto the muscles of the pelvic diaphragm, including the pubococcygeus and iliococcygeus, located at the 5 and 7 o'clock positions, superficially and deep inside the vagina. This examination should serve to divide patients into those with and without pelvic floor dysfunction. Severe unrelenting pain may be noted with the placement of a Foley's catheter. Pelvic examination may not be able to be carried out in some patients due to the severe pain. In other patients, the pelvic examination is unremarkable, leading the clinician to doubt his or her diagnosis. However, lack of pelvic floor dysfunction should not lead to symptom dismissal, as ulcerative IC with underlying mucosal damage may not involve the pelvic musculature. Any concurrent prolapse or structural deficiency should also be noted. Generally prolapse does not lead to severe BPS symptoms; the examiner should be aware of associated incontinence, incomplete voiding, defaecatory dysfunction, or sexual interference from moderate/severe prolapse.

Laboratory investigations

Urinalysis, urine cultures, and vaginal wet preps are the first laboratory tests ordered when considering diagnosis. Vaginitis, yeast infection, and sexually transmitted infections may mimic these bladder and pelvic floor symptoms and should not be missed. Any haematuria should be investigated according to standard guidelines, including cross-sectional abdominal and pelvic imaging and cystoscopy. No findings from urine cytology specifically suggest a diagnosis and should be reserved for those with a high suspicion for urothelial carcinoma.

Urinalysis with microscopy and culture is not in itself diagnostic, but is one of the most commonly used differentiating tests.[1][3] The result is usually normal in these patients. A positive culture points toward an infectious aetiology. If pyuria or microscopic haematuria is present, further evaluation is warranted for fastidious organisms (Ureaplasma, Mycoplasma, acid-fast bacilli).

Cystoscopy

For patients with small maximum voided volumes, haematuria, or lack of pelvic examination findings, cystoscopy serves as a valuable diagnostic test. Confirmation of other pathology would change management, as would confirmation of ulcerative IC. While some studies did not demonstrate different symptomatology based on presence of ulcers, treatment decisions addressing ulcers can result in lasting relief for patients.[29][30]

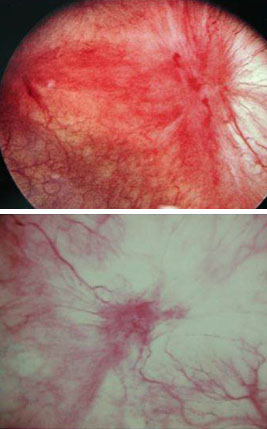

Cystoscopy is usually done with hydro-distension under regional or general anaesthesia. The bladder is filled to 80 cm with water for 2 minutes and gentle pressure held on the urethra to prevent leakage. The characteristic features of the ulcerative form are a diffusely erythematous bladder epithelium and 1 or more ulcerative patches (Hunner's ulcers) surrounded by mucosal congestion on the dome/lateral walls of the bladder. Gross inflammatory disease (i.e., Hunner's ulcers) may be detected, described as circumscriptive, reddened mucosal areas with small vessels radiating toward a central scar, with fibrin deposits or coagulum attached.[31][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Hunner's ulcers: larger mucosal haemorrhages seen after diagnostic cystoscopic hydro-distensionFrom the personal collection of Serge P. Marinkovic, MD [Citation ends]. Maximum bladder capacity under anaesthesia may be severely limited (<300 mL) and indicates an end-stage fibrotic bladder.

Maximum bladder capacity under anaesthesia may be severely limited (<300 mL) and indicates an end-stage fibrotic bladder.

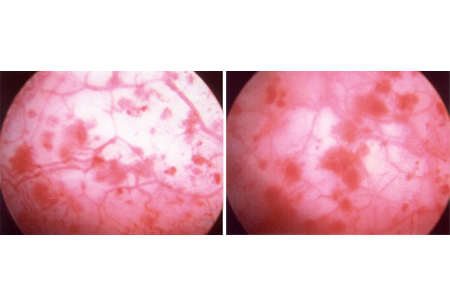

The non-ulcerative form of IC is epitomised by the same clinical symptoms as the classic form, but the cystoscopic findings present in the classic form are absent. However, after over-distension, many of these patients demonstrate glomerulations (discrete, tiny, raspberry-like lesions appearing as minuscule mucosal tears and haemorrhages).[32][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Glomerulations: haemorrhages seen after diagnostic cystoscopic hydro-distensionFrom the personal collection of Serge P. Marinkovic, MD [Citation ends].

The absence of glomerulations does not rule out the diagnosis, and many patients without symptoms may be found to have haemorrhages after hydro-distension. It should be noted that a negative cystoscopic examination does not rule out the diagnosis. Because symptoms and pathophysiology include pelvic floor dysfunction and afferent pain fibre up-regulation, the patient's voiding habits should serve as the guide to treatment and treatment response, not the presence of glomerulations.

Bladder biopsy

This is not a compulsory procedure, unless gross abnormalities of the bladder wall are found on cystoscopy. It is mainly used to exclude other diagnoses in the event of ulcerative IC. Grossly, these are indistinguishable from carcinoma in situ.

Potassium sensitivity test

Earlier work on phenotyping patients with IC/BPS included the response to noxious stimuli replicating the patient's pain. The instillation of potassium chloride is highly irritative and researchers theorised that the instillation of a rescue solution containing heparin would be predictive of treatment response. The test has been shown to be non-specific and should not be used in practice.

Experimental investigations

Assays for stress protein genes (e.g., mast cell tryptase, glycosaminoglycans, and Tamm-Horsfall protein autoantibodies) are used primarily in research studies and do not play a role in the diagnosis. They are not recommended unless as part of experimental protocols.

Some studies have revealed the presence of anti-proliferative factor (APF) in the urine of patients with IC/BPS.[33] APF inhibits bladder epithelial growth, and contributes to significantly decreased levels of heparin-binding epidermal growth factor (HB-EGF) and increased levels of EGF. Patients had APF activity, decreased HB-EGF levels, and increased EGF levels.[33] While the results may be promising, these assays are experimental and thus not yet commercially available.

Nerve growth factor (NGF) has recently become a favoured target of research. It has been shown to have been up-regulated in overactive bladder syndrome (OAB) and ulcerative interstitial cystitis. Treatment for OAB and IC/BPS has resulted in decreased level of NGF; however, the non-specific nature and poor specificity of this marker has prevented more widespread usage for phenotyping or treatment response.[34]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer