Aetiology

Virology

Infection is caused by the novel betacoronavirus MERS-CoV, an enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus with a genomic size of approximately 30,000 nucleotides.[34]

The virus is a member of the Coronoviridae family (order: Nidovirales; subfamily: Coronavirinae; genus Betacoronavirus) and is part of the lineage C group.[1][2] It is phylogenetically distinct from all previously known betacoronavirus species, which include human coronaviruses HKU1 and OC43, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus, and bat coronaviruses HKU4, HKU5, and HKU9.[3]

MERS-CoV genomes are classified into two clades: clade A (the earliest clusters of infection, i.e., EMC/2012 and Jordan N3/2012) and clade B (new clusters which are genetically distinct from clade A).[35]

Animal hosts

It is thought that dromedary camels are the primary animal host for MERS-CoV.[36][37]

Antibodies to the virus have been found in the serum of these camels in the Arabian Peninsula and its surrounding countries in multiple studies, some dating back to the 1990s.[37]

MERS-CoV RNA, as well as viable virus, has also been isolated from nasal and faecal samples from these camels.[38][39][40][41] The camels may show no sign of infection, but still excrete the virus in their nasal fluids, faeces, milk, or urine.

Experimental MERS-CoV infection in camels resulted in mild upper respiratory infection and mild fever.[42]

Bats are also thought to be an earlier reservoir of MERS-CoV; however, this is yet to be proven.[43]

Animal-to-human transmission

The exact mode of transmission is unknown, but it is thought to occur from direct or indirect contact with dromedary camels (e.g., camel milking, contact with camel nasal secretions, urine, or faeces) or camel products (e.g., unpasteurised camel milk, raw or undercooked camel meat).

Near-identical strains of the virus were isolated from epidemiologically linked dromedary camels and human cases in Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates.[31][44][45] The strongest evidence for camel-to-human transmission comes from one study in Saudi Arabia where the virus was isolated from a patient and one of his camels and the genome was found to be almost identical.[46][47] However, there are inconsistencies when it comes to camel-to-human transmission, and more data are required to gain a better understanding of how transmission occurs.[37][48]

A case-control study identified contact with camels to be a risk factor for MERS-CoV infection.[49]

Human-to-human transmission

The majority of confirmed cases are a result of human-to-human transmission (rather than camel-to-human transmission), with peaks of confirmed cases occurring during nosocomial outbreaks.[6][7][28] Despite this, human-to-human transmission is generally considered to be inefficient.

Transmission is via respiratory droplets (e.g., coughing, sneezing) from an infected patient, or close contact with an infected patient. However, airborne or fomite transmission cannot be ruled out.[50] The incubation period is 2 to 14 days and transmission is thought to occur during either the symptomatic or incubation stages.[8][51]

Transmission has been well documented in family clusters.[18][29][30] However, it has been reported more commonly in nosocomial outbreaks (e.g., haemodialysis units, intensive care units, medical wards).[6][7][29][30][31][32] This is likely to be due to factors which include late recognition of the infection, overcrowding of patients in hospitals, and inadequate infection control precautions.[6][10][30][52] Outbreaks are facilitated by extensive environmental contamination of the patients’ surroundings and the ability of the virus to survive for long periods on plastic and steel surfaces.[53][54]

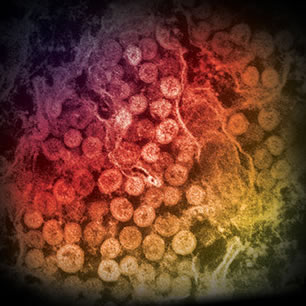

With an effective reproductive number of less than one, the epidemic potential of the infection is considered low at present unless the virus mutates.[55][56][57] Outbreaks are more restricted compared with SARS. Super-spreader events have not been reported; however, future adaptations of the virus may potentially increase human-to-human transmission or virus virulence.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Electron micrograph of a thin section of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) showing the spherical particles within the cytoplasm of an infected cellCenters for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [Citation ends].

Pathophysiology

The pathogenesis is not completely understood. The virus is transmitted primarily via respiratory droplets from an infected person which enter the human body via the respiratory tract mucosa.[58] The virus binds to the functional receptor dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP4; also called CD26) on the surface of host cells (e.g., type I and II alveolar cells, ciliated and non-ciliated bronchial epithelium, endothelium, alveolar macrophages, leukocytes). Binding is mediated by a receptor binding domain on the S1 subunit of the virus’ surface spike (S) proteins.[59][60] Membrane fusion and cell entry is facilitated by the S2 unit through the actions of 2 heptad repeat domains (HR1 and HR2) and a fusion protein.[61][62] The virus can also bind to DPP4 receptors in several species (e.g., camels, rabbits, sheep, goats, non-human primates).

DPP4 is expressed on the epithelial and endothelial cells of most human organs (e.g., kidney, liver, intestines). This may explain the multisystem clinical spectrum of the infection which includes severe (and sometimes fatal) pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and multi-organ failure.[63][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Negative stain electron microscopy showing Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) particles with characteristic club-like projections from the viral membraneCenters for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [Citation ends].

Classification

Virus taxonomy

MERS-CoV is a member of the Coronoviridae family (order: Nidovirales; subfamily: Coronavirinae; genus Betacoronavirus) and is part of the lineage C group.[1][2] It is phylogenetically distinct from all previously known betacoronavirus species, which include human coronaviruses HKU1 and OC43, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus, and bat coronaviruses HKU4, HKU5, and HKU9.[3]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer