Approach

Nausea and vomiting are common in children and are due to a diverse range of conditions. Despite there being many complex tests available, diagnosis primarily relies on a thorough history and physical examination.

Red-flag symptoms that should always be assessed, as they may require urgent management, include lethargy, fever, volume depletion, weight loss, bilious vomiting, haematemesis, papilloedema, abdominal tenderness, or the presence of a mass.

History

Nausea is characterised by the subjective unpleasant sensation of imminent vomiting. Often, the feeling can be localised in the stomach or throat, and is frequently accompanied by autonomic symptoms such as dizziness, pallor, and sweating. Vomiting is defined as the vigorous oral expulsion of the gastric or intestinal contents associated with contraction of the abdominal and chest muscles.

Nausea and vomiting frequently occur simultaneously in multiple conditions. Vomiting is usually preceded by nausea; the only exceptions are rumination syndrome, in which oral regurgitation is not preceded by nausea, and possibly gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD).

Nausea is not always followed by vomiting, as in conditions such as chronic functional nausea, postural nausea, and functional dyspepsia.

The following history should be elicited from the patient, parent, or carer.

Travel, food or fresh water intake, sick contacts: may indicate an infection.

Travel with passive movement: may indicate motion/travel sickness.

Previous trauma: may indicate concussion.

Ingestion of toxin(s) or use of medication(s): may indicate an environmental cause. Among the most common exposures in children aged ≤5 years are cosmetics, cleaning substances, analgesics, pesticides, cough and cold preparations, cardiovascular drugs, stimulants and street drugs, and essential oils.[68] Drug adverse effects: most commonly implicated include chemotherapy drugs, opioid analgesics, and anticholinergic drugs such as antidepressants or antispasmodics. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can cause nausea and vomiting secondary to gastrointestinal inflammation. Others include anaesthetics and antibiotics.

Family history: may indicate a chronic inflammatory condition, genetic conditions (e.g., metabolism disorders), or liver disorders.

Relation of symptoms to types of food: may indicate a food allergy.

The aetiology of the symptoms is often age-dependent and the following conditions present most commonly in each of the following age groups.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Aetiology of nausea and vomiting in children and adolescents grouped according to ageFrom the collections of Dr R.A. Gomez-Suarez and Dr J.E. Fortunato; used with permission [Citation ends].

It is important for the clinician to differentiate between acute and chronic symptoms.

The aetiology of chronic nausea is often difficult to define, and in order to better classify it, a consensus statement has been released by the Rome foundation. According to the Rome foundation, chronic nausea is defined as bothersome nausea occurring several times per week, not usually associated with vomiting, in the absence of endoscopic or metabolic disease. These criteria must be fulfilled for the last 3 months, with the symptom onset at least 6 months prior to diagnosis.[1] In the latest Rome IV consensus, a specific definition of chronic nausea for young children or adolescents was not included.[1][2]

Most cases seen in primary care are acute with symptoms that occur for less than one week. In this context, the severity of the symptoms and impact on the patient's health should be evaluated as the first priority. Specifically, the number and duration of episodes and ability to maintain hydration or adequate nutrition may need to be addressed before attempting to determine the cause.

Chronic symptoms may be associated with structural, inflammatory, malignant, or functional gastrointestinal or non-gastrointestinal disorders; therefore, a careful evaluation and referral should always be considered.

It is important for the clinician to be aware of the timing of a patient's symptoms: day or night; during sleep; or before, during, or after meals. This is particularly important with recurrent or chronic nausea and vomiting.

Frequency of the episodes can be classified as either cyclical (i.e., when asymptomatic periods occur, such as in cyclic vomiting) or continuous.

If symptoms occur during the morning and are associated with changes in posture (e.g., standing up), dysautonomia, postural nausea, and orthostatic tachycardia should be suspected.

If symptoms occur immediately after the patient eats, rumination should be suspected, particularly in the context of regurgitation without nausea. It appears to be more common in developmentally delayed children.

If symptoms occur later in the day or after meals/feeds with undigested food in the vomitus, gastroparesis should be considered. A delay in gastric emptying can be a common occurrence after a viral infection (post-viral gastroparesis).

If symptoms occur during the night and wake the patient up, or occur on waking, this may suggest more serious conditions such as intracranial hypertension, particularly when associated with severe headaches. Intracranial hypertension may be due to a brain tumour, pseudotumor cerebri (benign intracranial hypertension), hydrocephalus, infection, or ventriculoperitoneal shunt malfunction.

In the case of GORD, it is important to differentiate effortless regurgitation versus vomiting. Regurgitation generally occurs shortly after meals and can be associated with heartburn.

The characteristics of the vomitus, when present, are relevant to the diagnosis.

Vomitus may be digested food contents from the stomach, yellow in colour, bilious, or in some cases blood-tinged or frankly bloody.

Bilious vomiting is common in cases of intestinal obstruction like intestinal malrotation and small bowel atresia. It may also be present in Hirschsprung's disease.

Projectile vomiting (postprandial, non-bilious) is specific to pyloric stenosis.

Haematemesis is common in GORD, peptic ulcer disease (PUD), and bulimia nervosa.

It is not uncommon to see the vomitus evolve during multiple consecutive episodes: for example, changing from food content to bilious and then to bloody. Haematemesis under these circumstances may be due to ensuing Mallory-Weiss tears (mucosal tears at the gastro-oesophageal junction) due to retching or gastritis.

The presence of associated symptoms may help direct the clinician towards a diagnosis.

Diarrhoea (especially bloody, watery, or foul-smelling), abdominal pain, and fever are common presenting symptoms of gastroenteritis. Diarrhoea and abdominal pain may also indicate small bowel lymphoma.[31] If diarrhoea is explosive, it may indicate Hirschsprung's disease. Bloody diarrhoea may also indicate haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Haematochezia may indicate intussusception (may be described as currant jelly stool) or intestinal malrotation. Melaena may indicate peptic ulcer disease.

Fever, headache, photophobia, confusion, and nuchal rigidity may indicate meningitis. Nuchal rigidity is uncommon in children <2 years of age, but its absence does not exclude meningitis.

Fever may also indicate other infectious causes. Otalgia is characteristic of otitis media. Dysuria, urinary frequency, or flank pain may indicate a urinary tract infection or, if pain is severe, nephrolithiasis. Upper respiratory tract symptoms (e.g., cough, dyspnoea) may indicate pneumonia.

Headache, photophobia, and the absence of fever may suggest migraine as a precipitating factor. Symptoms may be preceded by an aura.

A baby being very hungry immediately after feeding (seems to be 'starving to death') is characteristic of pyloric stenosis.

Acute onset of severe testicular/scrotal or sharp abdominal pain may indicate testicular or ovarian torsion, respectively. Mid-epigastric pain that radiates through to the back may indicate acute pancreatitis.

Polyuria, polydipsia, and polyphagia can indicate diabetic ketoacidosis.

Dysphagia including choking, food impaction, as well as odynophagia may indicate eosinophilic oesophagitis; 50% to 60% of patients also have rhinitis or asthma.[46]

Failure to pass meconium within 48 hours of birthShou: may indicate Hirschsprung's disease or small bowel atresia.

Location of nausea can be very helpful in defining potential causes.

Nausea in the epigastric region can be linked to dyspepsia.

Patients who point to their neck/throat may have symptomatic GORD.

Physical examination

A complete physical examination is always warranted; however, patients often have no specific findings on examination. Every body system should be examined carefully.

Volume depletion: a decrease of more than 5% of the previous weight should raise concern about the possibility of volume depletion. The presence of tachycardia and hypotension with weight loss >10% to 15% is associated with a more pronounced hypovolaemia and the need for appropriate fluid resuscitation. Other signs of volume depletion include the presence of a sunken anterior fontanelle (in infants) or eyes, dry mucosal membranes, sticky saliva, loss of skin turgor, and slow capillary refill. Volume depletion may be associated with infections, an obstruction, or metabolic disorders.

Fever, pallor, and lethargy: typical signs of infection.

Wheezing or rales: may be revealed on chest examination and may indicate pneumonia.

Skin changes: jaundice, petechiae, or a purpuric rash may suggest an infectious process. Jaundice may also be seen in infants with pyloric stenosis, hepatitis A, or metabolism disorders. Hyperpigmentation of mucosa suggests Addison's disease. Loss of skin turgor suggests volume depletion, and pallor suggests anaemia.

Neurological signs: seizures, confusion/altered mental status, behavioural changes, nuchal rigidity, papilloedema, abnormal gait, vision dysfunction, cranial nerve paralysis, or retinal haemorrhages may be suggestive of trauma or intracranial hypertension. A bulging fontanelle in infants may also suggest intracranial hypertension. Amnesia may follow traumatic brain injury.

Acetone breath: specific for diabetic ketoacidosis. Other signs include tachycardia, hypotension, hyperventilation, and altered mental status.

Failure to thrive: a non-specific sign that can occur in metabolic disorders, obstruction, food allergies, and functional gastrointestinal disorders.

Unexplained symptoms may indicate factitious disorder. Symptoms that do not respond to medical management also support a diagnosis of the latter, or possibly cannabis hyperemesis syndrome.

The abdominal examination often gives multiple clues for the diagnosis.

Absence of bowel sounds and presence of abdominal distension: may suggest gastrointestinal obstruction.

Tenderness or pain on palpation: should alert the examiner to a possible acute abdominal inflammatory process such as enteritis or appendicitis.

Epigastric mass or visible peristalsis: can suggest pyloric stenosis in infants. A palpable mass may also indicate some other type of obstruction, or possibly gonadal torsion or nephrolithiasis, depending on the location of the mass.

Hepatomegaly: often seen in the context of metabolic conditions such as fructose intolerance or hepatitis A.

Right upper quadrant tenderness: suggests viral hepatitis or a toxic insult to the liver.

Costovertebral tenderness: present in teenagers with urinary tract infections, or patients with nephrolithiasis.

Bloating or distension may indicate gastroenteritis or an obstruction.

Rectal examination may be considered in difficult or atypical cases, but there is limited evidence to support its use in the diagnosis of functional constipation.[73][74] Rectal examination should only be undertaken by healthcare professionals competent to interpret features of anatomical abnormalities or Hirschsprung's disease.[75]

Otoscopy should be performed if otitis media is suspected (e.g., older children with otalgia or younger children who are seen to be pulling their ears). A bulging tympanic membrane and myringitis are diagnostic for otitis media.

Initial laboratory investigations

A complete medical history and physical examination guides which diagnostic tests should follow. Most cases do not require an extensive evaluation. Diagnostic testing should be directed by the clinical picture.[4]

A full blood count, renal function tests, liver function tests (LFTs), pancreatic enzymes, blood glucose level, serum ketones, arterial blood gas, urine culture, and urinalysis should be considered in all patients initially, particularly if the patient appears ill. Serum electrolytes should be ordered in patients with volume depletion in whom intravenous fluids may be needed. Lumbar puncture should be performed if meningitis or pseudotumor cerebri is suspected. Hepatitis A antibodies should be ordered if viral hepatitis is suspected. A positive faecal occult blood test raises concerns for gastrointestinal inflammatory conditions. Stool studies are useful if the patient has diarrhoea. Blood (or sputum) cultures may be ordered to confirm the presence of an infection. Drug urine/serum screens should be ordered if a toxic ingestion is suspected.

The presence of acidosis, ketosis, and hyperglycaemia suggests diabetic ketoacidosis. Haemolytic uraemic syndrome is characterised by the presence of microangiopathic anaemia, thrombocytopenia, and renal insufficiency. Anaemia can also occur in severe gastroenteritis, peptic ulcer disease, and eating disorders. Derangement of serum electrolytes can occur in many conditions including metabolic or endocrine disorders, eating disorders, toxin/medication ingestions, and any condition associated with volume depletion. White blood cell (WBC) count is usually elevated in infections, and peripheral eosinophilia indicates eosinophilic disease. Elevated LFTs may indicate hepatitis A, especially in the context of a positive test for hepatitis A virus immunoglobulins.

Initial imaging investigations

Frequently, no imaging is necessary, especially if the clinical presentation can be explained by the history and physical examination.

Relevant imaging studies include the following.

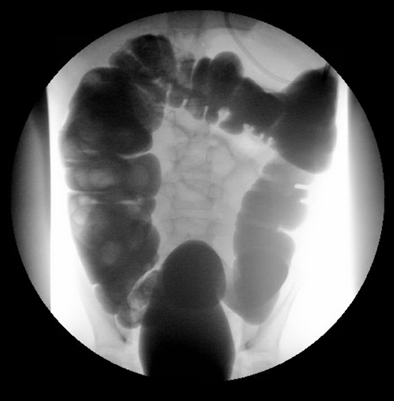

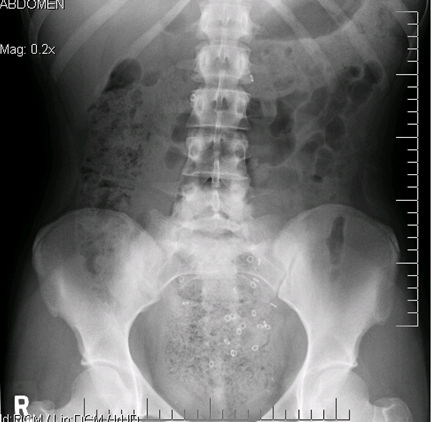

Plain abdominal x-rays (including an upright or cross-table lateral view): should be obtained if a bowel obstruction is suspected.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Abdominal x-ray showing faecal impaction in a patient with constipationFrom the collections of Dr R.A. Gomez-Suarez and Dr J.E. Fortunato; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Abdominal x-ray showing filled right colon and empty left colon and rectum in a patient with intussusceptionFrom the collections of Dr R.A. Gomez-Suarez and Dr J.E. Fortunato; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Abdominal x-ray showing filled right colon and empty left colon and rectum in a patient with intussusceptionFrom the collections of Dr R.A. Gomez-Suarez and Dr J.E. Fortunato; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Abdominal x-ray showing intestinal malrotation; note the small bowel is located to the right side of the midlineFrom the collections of Dr R.A. Gomez-Suarez and Dr J.E. Fortunato; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Abdominal x-ray showing intestinal malrotation; note the small bowel is located to the right side of the midlineFrom the collections of Dr R.A. Gomez-Suarez and Dr J.E. Fortunato; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Abdominal x-ray showing small bowel volvulus, a common cause of bilious vomitingFrom the collections of Dr R.A. Gomez-Suarez and Dr J.E. Fortunato; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Abdominal x-ray showing small bowel volvulus, a common cause of bilious vomitingFrom the collections of Dr R.A. Gomez-Suarez and Dr J.E. Fortunato; used with permission [Citation ends].

Ultrasound: in many centres, ultrasound is considered the test of choice in children before CT in order to avoid radiation exposure. Should be performed by an operator with experience in performing ultrasound in children. Useful in diagnosing hydrocephalus, pyloric stenosis, intussusception, appendicitis, nephrolithiasis, and gonadal torsion.

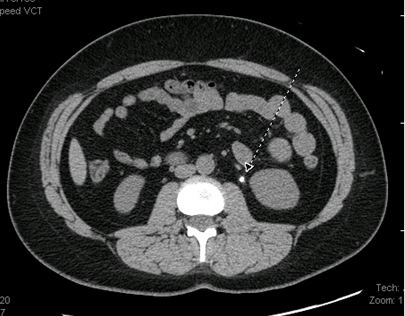

Computed tomography (CT) abdomen: may be obtained if an abdominal inflammatory condition is suspected (e.g., appendicitis, pancreatitis), particularly when supported by laboratory testing such as an elevated WBC count or elevated pancreatic enzymes.[80] It may also be ordered if obstruction, ovarian torsion, malignancy, or nephrolithiasis is suspected. In cases of suspected nephrolithiasis, intravenous contrast should not be used.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT abdomen showing small calcification in area of the left ureteral space, which corresponds to the presence of a kidney stoneFrom the collections of Dr R.A. Gomez-Suarez and Dr J.E. Fortunato; used with permission [Citation ends].

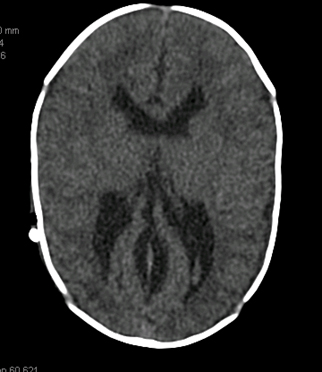

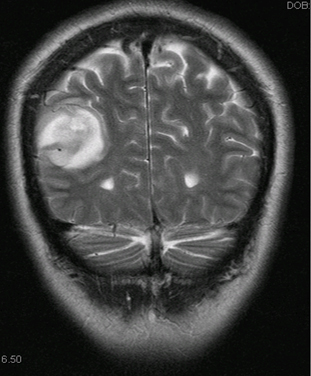

CT/magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) head: must be obtained if there is suspicion for intracranial hypertension, particularly if severe headaches accompany the symptoms. Ultrasound is preferred in newborns and small infants.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT showing increased volume of lateral ventricles secondary to non-communicating hydrocephalusFrom the collections of Dr R.A. Gomez-Suarez and Dr J.E. Fortunato; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT head showing right parietotemporal brain tumourFrom the collections of Dr R.A. Gomez-Suarez and Dr J.E. Fortunato; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT head showing right parietotemporal brain tumourFrom the collections of Dr R.A. Gomez-Suarez and Dr J.E. Fortunato; used with permission [Citation ends].

Chest x-ray: if pneumonia is suspected.

Subsequent investigations

The laboratory and imaging studies above are usually sufficient to address several common diagnoses; however, further testing may be required and may include the following.

Upper gastrointestinal series or abdominal CT or MRI enterography (useful for anatomical problems including intermittent or partial bowel obstruction: for example, intestinal malrotation, pyloric stenosis, superior mesenteric artery syndrome).

Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy or colonoscopy: useful to visualise bowel mucosa and obtain tissue samples for pathological analysis when inflammatory conditions are suspected.

Gastric emptying scintigraphy, electrogastrograms, or manometry: may be useful for conditions such as refractory gastroparesis or chronic unexplained nausea.

Enema: a barium enema is useful in diagnosing small bowel atresia or Hirschsprung's disease; a diagnostic enema may be used to aid diagnosis of intussusception and also act as a therapeutic intervention.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Barium enema showing transition zones in patients with Hirschsprung's diseaseFrom the collections of Dr R.A. Gomez-Suarez and Dr J.E. Fortunato; used with permission [Citation ends].

Sitz marker test: useful for refractory or chronic cases of constipation.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Sitz marker test showing retention of ingested markers in the rectosigmoid region in a patient with constipationFrom the collections of Dr R.A. Gomez-Suarez and Dr J.E. Fortunato; used with permission [Citation ends].

Small bowel biopsy: recommended in patients with chronic symptoms associated with vomiting (e.g., diarrhoea, abdominal pain). Can lead to the diagnosis of small bowel inflammation or infectious causes including giardiasis. May also be useful for diagnosing lactose intolerance.

Autonomic testing (including tilt table): useful when symptoms suggest dysautonomia as a primary mechanism for symptoms.

Food allergy tests (e.g., skin prick test) are indicated when a food allergy is suspected.

ECG or echocardiogram: useful in eating disorders for detection of arrhythmias.

For cyclic vomiting syndrome, additional diagnostic testing is contingent on a patient's presentation and obtained for the purposes of ruling out other conditions.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer