Aetiology

Pituitary masses may be classified based on their underlying aetiology: for example, pituitary adenoma, pituitary hyperplasia, non-adenomatous tumours, and vascular, inflammatory, or infective lesions.

Pituitary adenomas

Prolactinoma

Accounts for over 50% of all pituitary adenomas and are the most common clinically relevant pituitary adenoma.[1][7][8]

Adrenocorticotropic hormone-secreting (Cushing's disease)

While exogenous steroids are the most common cause of Cushing's syndrome in adults, Cushing's disease is the most common cause of endogenous Cushing's syndrome (70% to 80%).[9] Cushing's disease accounts for 4% of all functional adenomas.[1] The global prevalence is 2.2 cases per 100,000 people, with an incidence rate of 0.24 per 100,000 person-years.[10]

Growth hormone (GH)-secreting

The most common cause of acromegaly and accounts for 12% of all functional adenomas.[1] The global prevalence of acromegaly is 5.9 cases per 100,000 people, with an incidence rate of 0.38 cases per 100,000 person-years.[11]

Non-functional or gonadotrophin-secreting

Non-functional adenomas are the second most common cause of pituitary adenoma and account for up to 30% of all pituitary adenomas.[1] Most are gonadotroph cell adenomas.[12] All patients with clinically non-functional tumours should have an alpha-subunit glycoprotein determination. High-normal or elevated gonadotrophins in these patients are suspicious for an underlying gonadotroph adenoma.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Plain computed tomography scan showing a small pituitary mass encroaching on the right cavernous sinusBMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.08.2009.2193 [Citation ends].

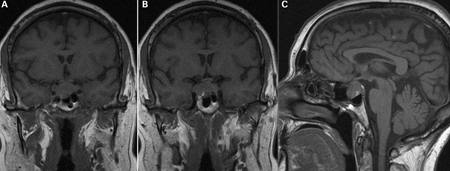

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A) Coronal T1 weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan showing a pituitary mass with expansion of the pituitary fossa. (B) Coronal T1 weighted MRI scan showing a pituitary mass extending into the cavernous sinus, particularly on the right. (C) Sagittal T1 weighted MRI scan of the pituitary tumourBMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.08.2009.2193 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A) Coronal T1 weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan showing a pituitary mass with expansion of the pituitary fossa. (B) Coronal T1 weighted MRI scan showing a pituitary mass extending into the cavernous sinus, particularly on the right. (C) Sagittal T1 weighted MRI scan of the pituitary tumourBMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.08.2009.2193 [Citation ends].

Thyrotropin (TSH) secreting

Accounts for <1% of all functional pituitary tumours.[1]

Pituitary hyperplasia

Lactotroph hyperplasia

Develops as a physiological response to pregnancy.

Thyrotroph hyperplasia

Develops in response to long-standing primary hypothyroidism.[13]

Gonadotroph hyperplasia

Develops in response to long-standing hypogonadism.

Somatotroph hyperplasia

Develops in response to ectopic secretion of GH-releasing hormone; usually associated with neuroendocrine tumours (pancreas, kidneys, adrenals, or lungs).

Corticotroph hyperplasia

A result of long-standing adrenal deficiency (e.g., untreated congenital adrenal hyperplasia) or in patients having undergone adrenalectomy for Cushing's disease.

Non-adenomatous benign tumours

Craniopharyngioma

Derived from squamous cell rests in the remnants of Rathke's pouch. Account for 1% to 3% of all adult intracranial tumours.[14]

Meningioma

Slow-growing tumours can originate from any dural surface. About 10% of meningiomas arise in the parasellar region.[15] Purely intrasellar tumours are rare.

Malignant tumours

Germ cell tumours

Rare intracranial tumours; incidence ranges from 0.3% to 0.5% of all intracranial tumours in Western countries, and higher in Asian countries.[16]

Lymphoma and chordoma

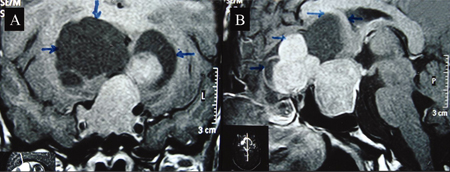

Sellar tumours that are extremely rare.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Coronal (A) and sagittal (B) post-contrast magnetic resonance image T1 weighted sections showing a large intrasellar tumour with suprasellar component. Suprasellar solid component shows a lobulated margin with peripheral non-enhancing cystic areas (margins shown by arrows), which are mildly hyperintense compared with cerebrospinal fluid in basal cisternsBMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.01.2009.1483 [Citation ends].

Metastatic disease

Metastases to the pituitary gland and sella are uncommon and account for less than 1% of sellar masses.[17] The most common primary malignancies to metastasise to the pituitary gland are breast and lung cancers.[18]

Pituitary carcinoma

Inflammatory/infective/iatrogenic

Hypophysitis

Lymphocytic hypophysitis: autoimmune disease that usually presents in women during or shortly after pregnancy; infrequent in men.

Drug therapy-induced hypophysitis: a recognised adverse effect of immunotherapy, particularly associated with anti-CTLA-4 antibodies and PD-1 inhibitors (immune checkpoint inhibitors used in the treatment of malignancy).[23] This complication is two to five times more common in males than females. Drug therapy-induced hypophysitis typically occurs in patients over the age of 60; its prevalence depends upon the medication used.[24][25][26]

Pituitary abscess

Rare and can develop following haematogenous spread of infection, extension from the sinuses, or meningeal sepsis.[27] Abscess development may arise in normal pituitary tissue or in a pre-existing sellar lesion (e.g., adenoma, craniopharyngioma, or Rathke cleft cyst), with or without a recent history of surgical treatment.[27]

Vascular

Cerebral aneurysms with intrasellar extension

Accounts for about 1-2% of all intracranial aneurysms.[28] Usually originates from the cavernous or supraclinoid portions of the internal carotid artery.

Pituitary apoplexy

Rare syndrome resulting from pituitary haemorrhage or infarction. Most commonly occurs within a pre-existing pituitary adenoma, but can occur in non-adenomatous lesions (e.g., a Rathke cleft cyst, sellar tuberculoma, hypophysitis, pituitary abscess, or craniopharyngioma).[29] Predisposing conditions include some drugs (e.g., anticoagulation therapy, dopamine agonist, gonadotrophin agonist), cardiac surgery, head trauma, and dynamic testing of pituitary function.[30]

Can also occur in normal pituitary tissue, during the peri- or postnatal period, as a consequence of hypovolaemic shock (Sheehan's syndrome).[29]

Other causes

Other lesions that may present as or mimic a pituitary mass include:

Rathke cleft cyst: an anatomical anomaly arising from craniopharyngeal duct remnants. They are common lesions, reported incidentally in up to 33% of autopsy cases.[31] They are two to three times more common in females than in males. They can be seen at any age but, when symptomatic, usually present between the ages of 40 and 60 years.

Empty sella syndrome: develops secondary to a communication between the pituitary fossa and the subarachnoid space. Cerebrospinal fluid herniates into the sella turcica, causing sella remodelling and enlargement, along with flattening of the pituitary gland. Predisposing conditions include congenital anatomical abnormalities, complications arising from a previous pituitary tumour (surgery, irradiation, or tumour infarction), and regression of the pituitary (e.g., following Sheehan's syndrome or hypophysitis).[32]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer