Gene-editing therapy, exagamglogene autotemcel, available through managed access agreement in National Health Service (NHS) England

Exagamglogene autotemcel, a gene-editing therapy, has been approved by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for use in the NHS in England for patients with severe sickle cell anaemia.

Patients aged 12 years and older with βS/βS, βS/β+ or βS/β0 genotype will be eligible for exagamglogene autotemcel, if they:

have recurrent vaso-occlusive crises (at least 2 during the previous 2 years), and

are suitable for haematopoietic stem cell transplant, but a human leukocyte antigen-matched donor is not available.

Exagamglogene autotemcel is a one-time gene therapy that uses CRISPR gene editing technology to alter the patient's own haematopoietic stem cells to produce higher levels of fetal haemoglobin in red blood cells.

The decision to approve exagamglogene autotemcel is based on clinical data from a multiphase, single-arm, open-label trial. In phase 3 of the trial, 29 of 30 patients (97%) who received exagamglogene autotemcel (and had sufficient follow-up to be evaluated) were free from vaso-occlusive crises for at least 12 consecutive months (mean duration of freedom from vaso-occlusive crises: 22.4 months).[102]

Final draft guidance and the managed access agreement are available from the UK NICE.[103]

The managed access agreement is a time-limited agreement that sets out the conditions under which people will be able to have NHS-funded treatment.[104]

Further data will be collected to address the uncertainties in the clinical or cost-effectiveness data.

Voxelotor withdrawn globally due to safety concerns

Voxelotor, indicated for the treatment of sickle cell disease, has been voluntarily withdrawn from the worldwide market by the manufacturer due to serious safety concerns.[93] This includes discontinuing all ongoing clinical trials, as well as compassionate use and expanded access programmes.

Healthcare professionals are advised to:

stop prescribing voxelotor for new patients with sickle cell disease

contact patients already taking voxelotor to advise on stopping treatment and discuss alternative options; patients must talk to their doctor before stopping voxelotor

monitor patients for adverse events after treatment with voxelotor is stopped, and ensure patients are followed-up appropriately

report adverse events to the relevant regulatory body.

The decision to withdraw voxelotor is based on clinical data that indicates the overall benefit of voxelotor no longer outweighs the risk in patients with sickle cell disease.

Higher rates of vaso-occlusive crises and deaths have been reported in patients taking voxelotor compared with placebo in clinical trials. Real-world registry studies also recorded higher rates of vaso-occlusive crisis in patients with sickle cell disease taking voxelotor.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) are currently conducting safety reviews of all the available data.[76][77]

Summary

Definition

History and exam

Key diagnostic factors

- parent(s) diagnosed with sickle cell anaemia, other sickle cell disease, or sickle cell trait

- persistent pain in skeleton, chest, and/or abdomen

- dactylitis

Other diagnostic factors

- high temperature

- pneumonia-like syndrome

- bone pain

- visual floaters

- tachypnoea

- failure to thrive

- pallor

- jaundice

- tachycardia

- lethargy

- maxillary hypertrophy with overbite

- protuberant abdomen, often with umbilical hernia

- cardiac systolic flow murmur

- shock

Diagnostic investigations

1st investigations to order

- DNA-based assays

- haemoglobin isoelectric focusing (Hb IEF)

- cellulose acetate electrophoresis

- high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)

- haemoglobin solubility testing

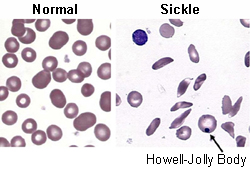

- peripheral blood smear

- FBC and reticulocyte count

- iron studies

Investigations to consider

- pulse oximetry

- plain x-rays of long bones

- bacterial cultures

- chest x-ray

Treatment algorithm

Contributors

Authors

Sophie Lanzkron, MD, MHS

Director

Sickle Cell Center for Adults

Associate Professor of Medicine and Oncology

Johns Hopkins Medicine

Baltimore

MD

Disclosures

SL declares consultancy (Bluebird bio, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Novartis, Magenta); honoraria (Novartis); research funding (Imara, Novartis, GBT, Takeda, CSL-Behring, HRSA, PCORI, MD CHRC); stocks (Pfizer, Teva). SL is on the executive board of the National Alliance for Sickle Cell Centers (uncompensated).

Acknowledgements

Dr Sophie Lanzkron would like to gratefully acknowledge Dr Channing Paller, a previous contributor to this topic.

Disclosures

CP declares that she has no competing interests.

Peer reviewers

James Bradner, MD

Instructor in Medicine

Division of Hematologic Neoplasia

Dana-Farber Cancer Institute

Boston

MA

Disclosures

JB declares that he has no competing interests.

Adrian Stephens, MB BS, MD, FRCPath

Consultant Haematologist

University College London Hospitals

London

UK

Disclosures

AS declares that he has no competing interests.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer