Approach

In a patient presenting with lymphadenopathy, the history should focus on the extent of lymphadenopathy (localized versus generalized), recent infectious exposures, the presence or absence of constitutional symptoms, travel, high-risk behaviors (intravenous drug use, unprotected sexual intercourse), and potential associated medications.

If lymphadenopathy is localized, examine the regions drained by the nodes for evidence of infection, skin lesions, or neoplasms. Approximately 75% of lymphadenopathies are reported to be localized, with the remaining 25% generalized (secondary to systemic disease).[27][28][29]

When the history and physical signs are diagnostic for a specific disorder, such as a localized skin infection or pharyngitis, no further testing is indicated and appropriate treatment should be initiated.

History

The key aspects of the patient's history that aid in the diagnostic workup, and in the differential diagnosis, are:

Age of the patient: a malignant etiology is more likely in older patients.[2] Cancers are identified in approximately 14% of patients who present with unexplained lymphadenopathy.[3] Among patients aged >65 years who present with enlarged lymph nodes, the risk of cancer is 28% within 1 year, rising to 42% within 10 years.[2]

Symptoms of infection: these include pharyngitis, conjunctivitis, skin ulceration, localized tenderness, genital sores or discharge, fever, and night sweats

Symptoms of metastatic cancer: constitutional symptoms of malignancy such as unintentional weight loss may be associated with localized symptoms such as difficulty swallowing, hoarseness and pain (in head and neck cancer), cough, and hemoptysis (in lung cancer)

Constitutional or "B symptoms": fever (>100.4ºF [>38°C]), night sweats, and/or unexplained weight loss greater than 10% of bodyweight over 6 months are concerning for malignancy, specifically a lymphoma; arthralgias, rash, and myalgias suggest the presence of an autoimmune disorder[30]

Epidemiologic clues: exposure to pets, occupational exposures, recent travel, or high-risk behaviors (intravenous drug use, unprotected sexual intercourse) may suggest specific disorders

Medication history: drug hypersensitivity (e.g., to phenytoin) is a common cause of lymphadenopathy

Duration of lymphadenopathy: persistent lymphadenopathy (more than 4 weeks) is indicative of chronic infection, collagen vascular disease, or underlying malignancy, whereas localized lymphadenopathy of brief duration often accompanies some infections (e.g., infectious mononucleosis or bacterial pharyngitis).

Physical exam

The most important physical exam findings are lymph node size, consistency, mobility, and distribution. Examining symmetry of lymph nodes from left and right sides of the patient can be helpful in distinguishing enlarged nodes.

Size: the significance of enlarged lymph nodes must be viewed in the context of their location, duration, associated symptoms, and patient age. Abnormal lymph nodes are generally larger than 1 cm in diameter (however, inguinal lymph nodes may be as large as 2 cm in healthy individuals). Lymph nodes greater than 2 cm that are persistent for more than 4 weeks should be evaluated. If there are no signs of systemic disease, lymph nodes measuring less than 1 cm can generally be observed.[1]

Consistency: assessment of lymph node consistency is not a reliable measure to distinguish between malignant and benign etiologies. In general, firm nodes are more commonly seen in malignancy. Tender nodes suggest an inflammatory etiology.[1]

Mobility: normal lymph nodes are freely moveable in the subcutaneous space. Abnormal nodes can become fixed or matted to adjacent tissues, or to other nodes by invasive cancers. Evaluation of the mobility of supraclavicular nodes is enhanced by having the patient perform a Valsalva maneuver during the examination.

Distribution: lymphadenopathy may be localized (enlarged lymph nodes in one region) or generalized (enlarged lymph nodes in 2 or more noncontiguous regions).[31] Generalized lymphadenopathy is usually a manifestation of systemic disease.

Location: palpable supraclavicular, popliteal, and iliac nodes are abnormal, as are epitrochlear nodes greater than 5 mm in diameter, and are more suggestive of malignancy. Inguinal lymph nodes may occasionally be enlarged in healthy individuals. Left supraclavicular adenopathy (“Virchow node”) suggests a gastrointestinal or thoracic cancer.[32]

Cervical lymphadenopathy

The cervical lymph nodes drain the scalp, skin, oral cavity, larynx, and neck. The most common causes of cervical lymphadenopathy are infection and malignancy. Common infectious causes are:

Bacterial pharyngitis

Dental abscess

Infectious mononucleosis

Tuberculosis

Tinea capitis (in children).

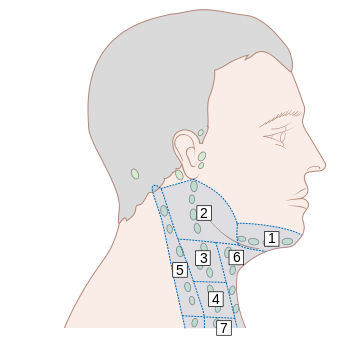

Common malignancies include head and neck cancers (especially in older patients with a history of smoking), and thyroid cancers. Ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy has an accuracy of 91% for distinguishing benign and malignant cervical lymph nodes.[33][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Lymph node groups in the head and neck; the numbers refer to the anatomic levels of the lymph nodesCancer Research UK [Citation ends].

Supraclavicular lymphadenopathy

This group of lymph nodes drains the gastrointestinal tract, genitourinary tract, and lungs. Enlarged supraclavicular nodes raise a strong suspicion for malignancy.[5] The prevalence of malignancy in the presence of supraclavicular lymphadenopathy is reported to be in the range of 54% to 85%.[34][35][36] Virchow node (pathologic enlargement of left supraclavicular lymph node) is associated with the presence of an abdominal or thoracic neoplasm.[32] Other common causes of supraclavicular lymphadenopathy include:

Hodgkin lymphoma

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

Bronchogenic carcinoma

Breast carcinoma.

Axillary lymphadenopathy

This group of lymph nodes drains the upper extremities, breast, and thorax. Causes of axillary lymphadenopathy include:

Cat scratch disease[37]

Streptococcal or staphylococcal skin infection including infected eczema

Metastatic breast carcinoma

Metastatic melanoma

Silicone breast implants.

Epitrochlear lymphadenopathy

This group of lymph nodes drains the ulna, forearm, and hand. Epitrochlear lymphadenopathy is a rare finding in healthy people.[38] Causes of epitrochlear lymphadenopathy include:

Lymphoma

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia

Infectious mononucleosis

Local upper extremity infections

Sarcoidosis

Secondary syphilis

HIV.

Inguinal lymphadenopathy

This group of lymph nodes drains the lower abdomen, external genitalia (skin), anal canal, lower third of the vagina, and lower extremities. Enlargement of inguinal lymph nodes up to 1 to 2 cm in size can be found in healthy adults.[1] In a diagnostic workup, biopsy of inguinal lymph nodes has been shown to offer the lowest diagnostic yield.[35] However, unilateral leg swelling (after deep vein thrombosis has been excluded) may require pelvic CT to rule out regional lymphadenopathy causing extrinsic compression by a tumor. Causes of inguinal lymphadenopathy include:

Cellulitis

Sexually transmitted infections

Hodgkin lymphoma

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

Metastatic melanoma

Squamous cell carcinoma (metastatic from the penile or vulvar regions)

Mpox infection; lymphadenopathy may be generalized; inguinal lymphadenopathy has been commonly reported.[39]

Mediastinal lymphadenopathy

The differential is extensive. Unilateral mediastinal lymphadenopathy can be secondary to infectious or malignant etiologies. Bilateral mediastinal lymphadenopathy may be caused by sarcoidosis or other chronic granulomatous diseases, as well as by malignant conditions. Calcified mediastinal lymph nodes may be due to tuberculosis, histoplasmosis, or silicosis.

Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle biopsy is increasingly used as a less invasive, alternative approach to mediastinoscopy for evaluation of mediastinal (and hilar) lymphadenopathy.[40] Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided biopsy can also be used to sample mediastinal lymph nodes, if no superficial lymphadenopathy is easily accessible.[26]

Abdominal lymphadenopathy

Lymphadenopathy limited to the mesenteric or retroperitoneal space is highly suspicious for underlying malignant disease. Periumbilical enlarged lymph nodes (which also include metastatic tumor deposits) are known as Sister Mary Joseph nodes, and are a classic sign of gastric adenocarcinoma. EUS-guided biopsy of abdominal lymphadenopathy is feasible.[26]

Splenomegaly

May be associated with lymphadenopathy in the following conditions:

Infectious mononucleosis

Acute leukemia

Non-Hodgkin and Hodgkin Lymphoma

Tuberculosis

HIV

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Investigations

If the history and physical exam are not diagnostic for a specific disorder, further testing is required. Initial investigations potentially include:

Complete blood count with white blood cell differential

Throat culture

Monospot test

HIV test

Hepatitis serologies

Purified protein derivative placement

Chest x-ray.

If the estimated risk for malignancy is low, patients with localized lymphadenopathy and nondiagnostic initial studies are observed for 3 to 4 weeks.

Biopsy

When malignancy is suspected, the optimal diagnostic test is a lymph node excisional biopsy. An excisional biopsy allows for histologic examination of intact tissue and is the best way to diagnose Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Indications for excisional biopsy and histologic examination include:

Patients with generalized lymphadenopathy in whom the initial studies are nondiagnostic

Patients with localized persistent lymphadenopathy, nondiagnostic initial studies, and a high risk for malignancy such as lymphoma

Patients presenting solely with cervical lymphadenopathy (or neck mass) who are at increased risk for malignancy. These patients should be considered for otolaryngology referral for evaluation of the larynx, base of tongue, and pharynx.[41]

If an excisional biopsy is not technically feasible, a core biopsy may be an alternative option. A core biopsy removes tissue from an enlarged lymph node and may allow the pathologist to assess nodal architecture if an adequate sample is provided.

Fine-needle aspiration is most useful to obtain cells for cytologic examination. There is a high false-negative rate due to sampling error, and lack of information regarding tissue architecture is a specific issue if lymphoma is in the differential diagnosis.[5][35]

Important considerations for histologic diagnosis:

Core biopsies have a better diagnostic yield than fine needle aspiration, and provide additional architectural information, but the procedure is more invasive.[42]

Fine needle aspiration of a lymph node is occasionally useful for the diagnosis of underlying carcinomas or recurrent malignancy.

Biopsy should be obtained from the most FDG-avid or largest lymph node. Whole-body positron emission tomography (PET) scan or integrated PET/computed tomography (CT) scan may be performed to help localize lymph nodes for biopsy for suspected malignancy, and have a higher diagnostic yield over standard CT scans in many tumor types.[43]

Avoid inguinal node biopsy, as the diagnostic yield at this site is often low.[31]

Avoid empiric therapy with corticosteroids or antibiotics in patients with nondiagnostic workups. Their lympholytic effect may confound the results of a lymph node biopsy.

Biopsies that are interpreted by the pathologist as atypical lymphoid hyperplasia should be considered nondiagnostic, rather than negative, for malignancy. These patients should be carefully followed and an additional lymph node biopsy strongly considered.

If suspicion for an underlying malignancy is high in patients, an unrevealing lymph node biopsy should be considered nondiagnostic, rather than negative, for malignancy. These patients will require further investigation.

Imaging

Imaging may be able to distinguish between benign and malignant lymphadenopathy without the need for more invasive tests. It can also be used to select a lymph node with features suspicious for malignancy for biopsy. Imaging can not replace biopsy when clinically indicated.

Ultrasonography

Malignant lymph nodes appear more "rounded" than a benign lymph node on ultrasound. The hilum of a malignant lymph node is not usually visible. Malignant nodes may demonstrate intranodal necrosis, reticulation (seen in lymphoma), calcification, and matting (fusion into a single ill-defined mass). Malignant nodes show peripheral or mixed peripheral and hilar blood flow with Doppler ultrasound, whereas benign lymph nodes have hilar blood flow.[44] Ultrasound elastography (a qualitative method of evaluating tissue stiffness), is increasingly used in endoscopic and endobronchial ultrasound to discriminate between benign and malignant lymph nodes.[45][46]

Computed tomography (CT)

Can provide quantitative information about the water, iodine (contrast), fat, and calcium content of lymph nodes, which can help distinguish benign from malignant lymph nodes. This may help to stage head and neck cancers, and to plan surgical intervention.[47]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer