History and exam

Key diagnostic factors

common

ill-defined ache

A patient may note the insidious onset of an ill-defined ache localized to the anterior knee behind the patella. Occasionally, the pain may be centered along the medial or lateral patellofemoral joint and retinaculum.

pain aggravated by compressive force

Pain can be aggravated by activities that increase patellofemoral compressive force, which include ascending and descending hills or stairs, squatting, and prolonged sitting with the knee in a flexed position.[5]

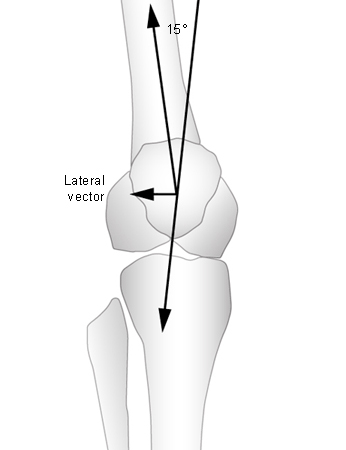

Q angle

The Q angle is formed by the line connecting the anterosuperior iliac spine to the center of the patella and the line connecting the center of the patella to the middle of the anterior tibial tuberosity.[26][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Q angleCreated at BMJ Evidence Centre [Citation ends].

It is a measure of patellar tendency to move laterally when the quadriceps muscles are contracted. The Q angle should be measured to determine whether this value falls within the normal range.

The patient should be in a supine position with the knees extended and the legs relaxed.

Most practitioners accept 10° to 15° as a normal range for the Q angle when the knee is extended or slightly flexed.[33] The greater the Q angle, the greater the patellar tendency to move laterally.

The difference in Q angles between men and women may be due to differences in average height, so height may be used as a correction factor.[45][46][47] Lower Q angles are associated with taller patients.

pain on palpation of patellar retinaculum

If pain results from gentle palpation, this test is considered positive.

patellar tilt test

Lateral patellar tilt suggests tight lateral structures contributing to patellofemoral pain syndrome. One way to evaluate the patellar tilt is by comparing the height of the medial and lateral border of the patella. With the patient lying supine with knee extended and the quadriceps relaxed, the examiner places the thumb and index fingers on the medial and lateral border of the patella. If the finger close to the medial border is more anterior than the lateral border, then the patella is tilted laterally.[33]

mediolateral glide test

A 5 mm lateral displacement of the patella causes a 50% decrease in vastus medialis oblique tension.[36]

patellar mobility test

Lateral patellar mobility of 3 quadrants suggests an incompetent medial restraint.

Medial mobility of only 1 quadrant is consistent with a tight lateral restraint.

Medial mobility of 3 or more quadrants suggests a hypermobile patella.

Hypermobility with lateral patellar glide is correlated with laxity of the medial patellofemoral ligament or the patellomeniscal ligament and is often noted in association with patellar subluxation.[13][14]

patellar apprehension test

Lateral movement of the patella results in the patient becoming apprehensive at the point of maximum passive displacement.

patellar maltracking test

decreased muscle flexibility

muscle weakness

Quadriceps muscle or hip abduction and external rotation muscle weakness is often seen in patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome.[16][21][50]

In athletes, manual muscle testing does not consistently detect muscle strength deficits or clearly demonstrate the effect of such deficits on the knee, so functional performance testing may be preferred.

Functional performance tests simulate the demands of weight-bearing sport participation on the knee and the entire lower limb kinetic chain.

Risk factors

strong

bony and structural abnormalities

iliotibial band tightness

Tightness of the iliotibial band (ITB) can affect normal patella excursion. The distal ITB fibers blend with the superficial and deep fibers of the lateral retinaculum, and tightness in the ITB can contribute to lateral patellar tilt and excessive pressure on the lateral patella.[5]

abnormal patellar mobility

There is an association between patellar hypomobility and a tight iliotibial band. Hypermobility with increased lateral patellar glide is correlated with laxity of the medial patellofemoral ligament or the patellomeniscal ligament and is often noted in association with patellar subluxation or dislocation.[13][14][15]

quadriceps muscle weakness

Quadriceps muscle weakness is often seen in patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome.[16][17] However, the mechanism by which strengthening improves patellofemoral pain symptoms is not entirely clear. Improved quadriceps strength may improve patellar tracking or lead to more subtle changes in patellar contact and pressure distribution. Quadriceps muscle activation imbalance due to delayed activation of the vastus medialis has also been reported as a contributing factor of patellofemoral pain, particularly in those with documented maltracking.[8][18]

subtalar joint pronation

Hyperpronation of the foot is a causative factor for this condition.[19] In theory, increased pronation causes the tibia to internally rotate during the weight acceptance phase of gait, preventing the tibia from fully externally rotating during midstance and so preventing the knee from fully locking via the screw-home mechanism. To compensate, the femur internally rotates to allow the knee to fully lock. Femoral internal rotation during quadriceps contraction may cause a greater lateral force on the patella as it is compressed against the lateral trochlear groove.

hip internal rotation

Increased femoral internal rotation leads to increased contact pressure between the patella and the lateral trochlear groove, which can increase subchondral bone stress and patellofemoral pain syndrome symptoms.[20] Hip muscle weakness in abduction and external rotation can cause increased femoral internal rotation in patients with patellofemoral pain.[21]

gait deviations

Deviations in gait can give rise to patellofemoral pain, especially in runners. Hyperextension of the knee and decreased knee flexion on weight acceptance, which reduce shock absorption, can often lead to patellofemoral pain.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer