Recommendations

Key Recommendations

Acute mesenteric ischemia is a life-threatening emergency. Clinicians must maintain a high index of suspicion for bowel ischemia, because the signs and symptoms are relatively nonspecific yet the condition has significant morbidity and mortality, particularly if diagnosis is delayed.[30] Time is of the essence to improve outcomes; early recognition, appropriate diagnostic studies, and aggressive treatment should be instigated emergently and expeditiously.

In the absence of highly specific or definitive signs and symptoms, a history and physical exam alone are generally not sufficient to make the diagnosis; imaging is typically required. However, when fulminant ischemic bowel disease is present, it may not be appropriate for extensive diagnostic testing to delay appropriate surgical intervention.

Where clinically indicated, resuscitation should be administered in parallel with the diagnostic workup in order to minimize the risk of ischemia progressing. Resuscitation should include administration of supplemental oxygen, adequate fluid replacement, and correction of acute heart failure or arrhythmias.

Clinical presentation and history

Presenting features and history may vary widely because bowel ischemia encompasses a wide spectrum of disorders.

History taking should be thorough in order to be able to confidently exclude other potential diagnoses. The history should explore the key characteristics of the abdominal pain, using the mnemonic SOCRATES:

Site

Onset

Character

Radiation

Associations - nausea, vomiting, diarrhea

Timing, duration, frequency

Exacerbating and relieving factors

Severity

Patients with acute ischemia typically present with severe abdominal pain that is out of proportion to findings on physical exam.[17] The pain may also be diffuse and have a sudden onset.[17] Chronic symptoms of vague, diffuse abdominal pain may be indicative of chronic mesenteric ischemia.[31] Patients may also report long-standing postprandial abdominal pain and fear of eating.[17][31] In contrast, colonic ischemia may cause focal or diffuse abdominal pain and often has a more insidious onset, over several hours or days.

Other important elements to elicit include smoking history, cardiovascular risk factors, comorbidities, and past medical history. Suggestive findings for each of the possible types of ischemic bowel disease are as follows.

Acute mesenteric ischemia

Most patients present with sudden abdominal pain, often periumbilical. The classic presentation is pain disproportionate to the physical exam findings.[11][24] The pain generally persists and worsens. As ischemia progresses to infarction, the pain may become more diffuse.[24] Nausea and vomiting may also be present.

The patient may be severely sick in a delayed presentation, where the bowel ischemia is extensive or has progressed to infarction.

Patients with arterial embolus may describe sudden, severe abdominal pain with rapid, forceful bowel evacuation, possibly containing blood. Arterial embolus is the most common cause of acute mesenteric ischemia.[17] Acute mesenteric ischemia due to arterial embolus should be suspected in patients who describe sudden, severe abdominal pain with:[17]

Rapid, forceful bowel evacuation, possibly containing blood, and/or

High risk of thromboembolism.

Patients with mesenteric venous thrombosis have more variable presentations than patients with arterial etiology.

Pain is often tolerated initially.

Typically, these patients describe colicky abdominal pain for a mean of 5 to 14 days before presentation; 25% of patients have had episodes of pain for >30 days before presentation.

About 60% to 70% of these patients have associated nausea and vomiting, and 30% have diarrhea or constipation.[32]

A longer duration of symptoms before presentation in venous ischemia may be associated with improved outcomes.[24]

Older patients with longstanding congestive heart failure, cardiac arrhythmias, recent myocardial infarction, hypotension, or peripheral vascular disease are at higher risk for acute mesenteric ischemia than younger patients.

Younger patients may have a history of collagen vascular disease, vasculitis, hypercoagulable state, vasoactive medication, or cocaine use.

Intestinal mesenteric ischemia should be considered if the clinical picture does not suggest another abdominal pathology.[33]

Chronic mesenteric ischemia

Typically of insidious onset with repeated, mild, transient, episodes over many months, becoming progressively more severe over time. The pain is poorly localized. Pain often occurs after meals, gradually resolving over a few hours.

Patients may report long-standing postprandial pain and may develop fear of eating (sitophobia).[17][31]

There may be significant weight loss, giving the patient a cachectic appearance.[31]

Patients may have associated nausea, and diarrhea with or without blood.[31]

The "classic triad" of chronic mesenteric ischemia is postprandial pain, weight loss, and an abdominal bruit; however, this is found in only a minority (around 20%) of patients.[31]

Infarction of bowel is uncommon, as insidious onset allows some collateral circulation to develop.

Chronic mesenteric ischemia usually occurs in older people. Women are affected more than men (ratio 3:1).

Patients frequently give a history of heavy smoking and other symptoms associated with atherosclerosis.

Celiac compression syndrome is a type of chronic mesenteric ischemia that occurs due to the median arcuate ligament compressing the celiac axis.[17]

Consider this diagnosis particularly in younger patients (especially women) with unexplained abdominal pain and normal upper endoscopy as well as normal liver, pancreatic, and gastric laboratory studies, particularly in those patients who have an abdominal bruit (from a partially obstructed flow in the celiac axis).

Patients may describe having become fearful of eating (sitophobia).

Colonic ischemia

Soon after the onset of ischemia, there is usually pain with frequent bloody, loose stools, reflecting mucosal or submucosal damage. However, blood transfusion is rarely needed. Passage of maroon or red blood from the rectum is particularly characteristic of colonic ischemia.

Patients typically describe mild to moderate pain that is usually felt peripherally, in contrast to the pain of acute mesenteric ischemia, which is often described as periumbilical. The ischemia is commonly in the "watershed" areas of the colon (the areas of the colon between two major supplying arteries; see Pathophysiology), hence the pain is typically left-sided. Tenderness to palpation over the affected bowel occurs from early in the course of ischemia, in contrast to acute mesenteric ischemia, where tenderness is a relatively late sign.

Patients do not generally appear severely sick, unless fulminant ischemia is present.

If colonic ischemia progresses, pain becomes more continuous and diffuse. The abdomen becomes more distended and tender and there are no bowel sounds.

If ischemia progresses further still and necrosis approaches, there is a significant leakage of fluid, electrolytes and protein through the damaged mucosa, with shock and metabolic acidosis.

Important risk factors for colonic ischemia are:[27]

Age >60 years

About 90% of cases occur in patients >60 years

Hemodialysis

Hypertension

Hypoalbuminaemia

Diabetes mellitus

Constipation-inducing medications

Colonic ischemia is increasingly identified in younger people, associated with strenuous and prolonged physical exertion (e.g., long-distance running), various medications (e.g., oral contraceptives), cocaine use, and coagulopathies (e.g., protein C and S deficiencies, antithrombin III deficiency, activated protein C resistance).[7]

Colonic ischemia may also occur:

Following aortic or cardiac bypass surgery

In association with vasculitides such as systemic lupus erythematosus or polyarteritis nodosa, infections (e.g., cytomegalovirus, Escherichia coli O157:H7), coagulopathies

After any major cardiovascular episode accompanied by hypotension

With obstructing or potentially obstructing lesions of the colon (e.g., carcinoma, diverticulitis).

Diagnosis is by colonoscopy or contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) imaging.[7] More than 80% of cases resolve spontaneously or with conservative measures, but surgery may be required in acute, subacute, or chronic cases. Predictors of poor outcomes include a lack of rectal bleeding and right-sided ischemia.[34]

Nonocclusive ischemia (mesenteric or colonic)

Typically seen in patients with underlying hypotension and volume deficits, which may be related to congestive heart failure, hypovolemia, sepsis, and cardiac arrhythmias, or hemodialysis.[17][32] Systemic hypotension leads to mesenteric vasoconstriction and nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia. In 95% of cases, colonic ischemia occurs due to sudden but transient reduction in colonic blood flow due to nonocclusive causes.[7] This happens most of the time due to small vessel disease (type I disease) and rarely due to systemic hypotension (type II disease).

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Comparison of symptoms/signs and investigations for the three types of ischemic bowel diseaseDesigned by BMJ Knowledge Centre, with input from Dr Amir Bastawrous [Citation ends].

Physical exam

Examination should begin with an assessment of vital signs to determine if immediate resuscitation measures are required. This should be followed by a thorough exam of all systems, particularly focusing on the abdomen and cardiovascular system, for clues that may help secure the diagnosis. When bowel ischemia is associated with vasculitis or specific disease entities, characteristic dermatologic, musculoskeletal, or further findings specific to the disease may be present.

Abdominal exam

Early in the course of acute mesenteric ischemia the abdomen may initially be soft and non- or minimally tender to palpation. Typically, patients with acute mesenteric ischemia initially report levels of abdominal pain greater than would be expected by the physical findings.[17]

Patients with colonic ischemia may have mild-to-moderate tenderness at an earlier stage in the course of ischemia, which is felt more laterally over the affected parts of the colon compared with the pain and tenderness of acute mesenteric ischemia which is generally more periumbilical.

As ischemia progresses towards infarction, patients develop signs of peritonitis, with a rigid, distended abdomen, guarding and rebound, percussion tenderness, and loss of bowel sounds.

It is imperative to consider and either diagnose or exclude acute mesenteric ischemia in patients who present with severe abdominal pain and a paucity of significant abdominal findings. The dangers of a delay in diagnosis outweigh the risk of early invasive studies.[32]

Auscultation of the abdomen reveals an epigastric bruit (indicative of turbulent flow through an area of vascular narrowing) in 48% to 63% of patients.[23]

Rectal exam may demonstrate gross blood per rectum or microscopic blood upon testing for occult hemorrhage.

Peritonitis indicates need for urgent surgical intervention.

Cardiovascular exam, including ECG

ECG may demonstrate arrhythmias that predispose to cardioembolic complications, such as atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter, or acute infarction that may be the etiology of intestinal ischemia.

Cardiovascular exam may reveal bruits on carotid auscultation, along with skin changes, absent hair, and absent distal pulses on the limbs, consistent with advanced atherosclerotic disease.

Laboratory tests

Initial blood work should include tests to direct initial resuscitation, help assess the severity of any ischemia, and suggest clues to any alternative diagnoses.[35]

Complete blood count

More than 90% of patients with acute mesenteric ischemia will have an abnormally elevated leukocyte count.[11]

Chemistry panel including C-reactive protein[35]

Helps assess renal dysfunction and dehydration, frequently present in patients with ischemic bowel disease.

Liver function tests[35]

May be elevated, as a consequence of septic shock or concomitant with bowel ischemia.

Arterial blood gases and serum lactate

Metabolic acidosis is a common finding in patients with acute mesenteric ischemia.[11]

Elevated serum lactate does not determine the presence or absence of ischemic or necrotic bowel; however, it can be used to assist with making the diagnosis and determining the severity.[11]

Coagulation panel, type and screen, cross match

Aids in the diagnosis of any underlying coagulopathy as a risk factor for further thrombosis.[35] Allows correction of any clotting dyscrasia as part of treatment.

Type and screen in preparation for the possibility of transfusion.

Serum amylase

Elevated serum amylase is found in approximately half of patients with acute mesenteric ischemia.[11]

D-dimer

May be elevated in intestinal ischemia, but its use is limited because D-dimer is a very nonspecific test.[11] However, if D-dimer is normal, the likelihood of mesenteric ischemia is very small.

Imaging

If mesenteric ischemia is suspected, CT angiography (CTA) of the abdomen and pelvis should be performed as the first-line investigation in order to diagnose ischemia, identify the underlying cause, and detect any complications or alternative diagnoses.[17][24][31][36][37]

If intervention is suitable, imaging can also assess the target vessels for revascularization, the degree and nature of the stenosis or occlusion, and potential approaches to arterial access.[17] Imaging can also inform pathologic staging; the degree of involvement of each layer of the gastrointestinal tract (mucosa, submucosa, muscularis, and serosa) can be used to estimate the probability of reversibility of the ischemia, therefore helping to guide treatment.[38]

In cases of acute ischemia, if CT is not immediately available, prompt exploratory laparotomy is indicated in patients with suspected ischemic bowel. Laparotomy without prior imaging may be indicated in unstable patients with peritoneal signs.

CTA

The preferred first-line investigation in the diagnosis of acute ischemia.[17][36] Scanning should be considered even in the presence of renal impairment in order to save life and prevent worsening renal injury.[11][12][24][36]

Should be performed in the noncontrast, arterial, and portal venous phases (known as a "triple phase" scan).[17]

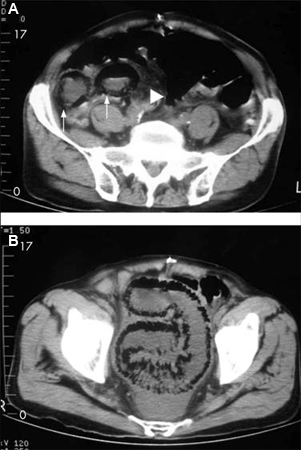

Helpful in diagnosing acute mesenteric ischemia, but findings can be nonspecific in early ischemia; late signs indicate necrotic bowel, which requires immediate surgical intervention.[17] Early signs include bowel wall thickening and luminal dilation.[17] Late signs include pneumatosis (gas in the bowel wall) and mesenteric or portal venous gas, which typically indicate necrotic bowel.[17][32][39] Other late signs include edematous bowel, and variable enhancement of the bowel surrounded by free fluid.[17] May also show thickening of the bowel wall with thumbprinting sign suggestive of submucosal edema or hemorrhage. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan: colonic thickening with pneumatosis intestinalisFrom the collection of Dr Jennifer Holder-Murray; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: 84-year-old man presenting with symptoms suggestive of ischemic bowel disease: (A) Abdominal CT revealing a massive circumferential and band-like air formation as intestinal pneumatosis (arrows) and pronounced edema of mesenteric fat (arrowhead) around necrotic bowel loops; (B) Another slice of abdominal CT showing long segmental pneumatosis of the small bowelLin I, Chang W, Shih S, et al. Bedside echogram in ischaemic bowel. BMJ Case Reports. 2009:bcr.2007.053462 [Citation ends].

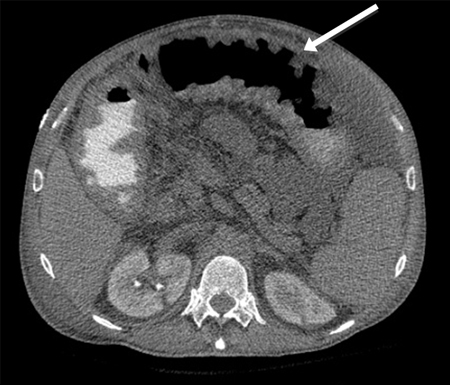

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: 84-year-old man presenting with symptoms suggestive of ischemic bowel disease: (A) Abdominal CT revealing a massive circumferential and band-like air formation as intestinal pneumatosis (arrows) and pronounced edema of mesenteric fat (arrowhead) around necrotic bowel loops; (B) Another slice of abdominal CT showing long segmental pneumatosis of the small bowelLin I, Chang W, Shih S, et al. Bedside echogram in ischaemic bowel. BMJ Case Reports. 2009:bcr.2007.053462 [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan: circumferential wall thickening of the transverse colon; white arrow shows thumbprintingFrom the collection of Dr Amir Bastawrous; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan: circumferential wall thickening of the transverse colon; white arrow shows thumbprintingFrom the collection of Dr Amir Bastawrous; used with permission [Citation ends].

Can identify the underlying cause of ischemia, bowel complications, and other causes of acute abdominal pain.[17]

Superior mesenteric artery (SMA) embolism can be identified by an occlusive filling defect in the proximal SMA.[17]

SMA thrombosis may be identified by calcified atherosclerotic plaque involving the aorta and its major branches, and proximal short-segment occlusion of the proximal SMA.[17]

Nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia (NOMI) is difficult to diagnose using CTA because of the challenge of identifying vasospasm of the mesenteric arterial branches.[17] Vasospasm may be identified by a beaded appearance of the affected mesenteric vessels, with narrowing of multiple small branches.[17] CTA may detect the degree of ischemic bowel, which may appear as segmental and discontinuous thickening of the bowel wall and hypoenhancement.[17] In addition, key negative findings, such as patency of arterial vessels and lack of atherosclerosis, may rule out causes of occlusive ischemia.[17]

Mesenteric vein thrombosis (MVT) can be identified in the acute phase by expansile filling defects with peripheral enhancement of the mesenteric-portal veins. CTA may also show mesenteric venous engorgement, fat-stranding, and edema.[17]

Chronic mesenteric ischemia may be identified by severe ostial narrowing or occlusion of at least two of the three mesenteric arteries.[17]

CTA has replaced conventional angiography as standard practice for evaluation of the mesenteric vasculature and diagnosis of acute mesenteric ischemia.[31][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT angiogram: acute superior mesenteric artery thrombusFrom the collection of Dr Jennifer Holder-Murray; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT angiography: 3-dimensional reconstruction with superior mesenteric artery stenosis from severe atherosclerotic plaque in a patient on follow-up imaging for endovascular aneurysm repairFrom the collection of Dr Jennifer Holder-Murray; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT angiography: 3-dimensional reconstruction with superior mesenteric artery stenosis from severe atherosclerotic plaque in a patient on follow-up imaging for endovascular aneurysm repairFrom the collection of Dr Jennifer Holder-Murray; used with permission [Citation ends].

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA)

MRA may have a role in making the diagnosis of chronic mesenteric ischemia. However, CTA is likely a better exam than MRA for the diagnosis of chronic mesenteric ischemia because of its capacity for higher resolution in combination with faster scans.

MRA may be considered with and without contrast if acute mesenteric ischemia is suspected.[17] However, compared with CTA, MRA is less likely to identify signs of ischemia such as pneumatosis or portal venous gas; the time required to perform an MRA exam, and the possible need for bowel stimulation with a meal, limit the usefulness of MRA in the diagnosis of acute mesenteric ischemia.[17]

Abdominal x-ray

Abdominal x-ray has a limited role in the diagnosis and evaluation of acute mesenteric ischemia.[11][24] A negative radiograph does not exclude the diagnosis.[11]

Plain x-rays are often normal early in the course of ischemia or when ischemia is mild. Abdominal x-ray is therefore not recommended in the diagnosis of intestinal ischemia.[11]

With worsening ischemia, plain x-rays may show formless loops of bowel, ileus, or thickening of the bowel wall with thumbprinting sign suggestive of submucosal edema or hemorrhage. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Plain abdominal x-ray: shows marked wall thickening of the transverse colon compatible with the finding of thumbprinting (white arrows)From the collection of Dr Amir Bastawrous; used with permission [Citation ends].

Erect chest x-ray

May show subdiaphragmatic air, indicative of perforation of the bowel requiring prompt surgical intervention.

Mesenteric angiography[32]

Historically this has been the definitive test for diagnosing mesenteric ischemia. In current practice it is usually preceded by positive CTA in the acute setting.

Sensitivity is 74% to 100%, specificity 100%.[32]

Occlusive ischemia demonstrates a proximal defect in the angiogram without distal filling of the mesenteric arcades.

Nonocclusive ischemia may cause vasoconstriction of all mesenteric arcades. Mesenteric angiography can therefore diagnose NOMI before infarction occurs. Four criteria are used for this purpose:

Narrowing of the origins of the SMA branches

Irregularities in these branches

Spasm of the mesenteric arcades

Impaired filling of the intramural vessels.

Enables treatment by infusion of vasodilators or thrombolytic agents (which have been shown to improve outcome). Often performed with the intention of proceeding to intervention.

For the diagnosis of chronic mesenteric ischemia due to atherosclerotic disease, angiography needs to demonstrate severe occlusion of at least 2 of the 3 splanchnic vessels, although in the absence of symptoms an abnormal angiography result alone is not sufficient for diagnosis.[36]

Sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy

Sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy with biopsy should be done within 48 hours to confirm the diagnosis of ischemic colitis.

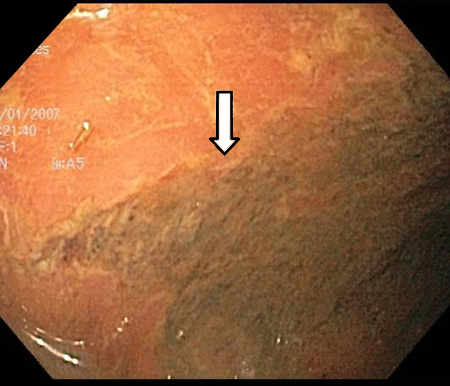

In nongangrenous ischemic colitis, colonoscopy may show a highly specific sign - a single linear ulcer running longitudinally along the antimesenteric colon wall (colon single-strap sign). Nonspecific signs include erythema, fragility, edema of colon mucosa, scattered hemorrhagic erosions, scattered petechial hemorrhages with pale areas, bluish hemorrhagic nodule due to submucosal hemorrhages, and rarely mass-like lesion mimicking malignancy.

If urgent surgical intervention is required due to the condition of the patient, surgery should not be delayed to carry out sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Colonoscopy: demarcation between ischemic and normal colonFrom the collection of Dr Jennifer Holder-Murray; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Colonoscopy: denudation of colonic mucosaFrom the collection of Dr Jennifer Holder-Murray; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Colonoscopy: denudation of colonic mucosaFrom the collection of Dr Jennifer Holder-Murray; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Colonoscopy: mucosal sloughing and likely nonviable colonFrom the collection of Dr Jennifer Holder-Murray; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Colonoscopy: mucosal sloughing and likely nonviable colonFrom the collection of Dr Jennifer Holder-Murray; used with permission [Citation ends].

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy can be used in patients with suspected chronic mesenteric ischemia to rule out alternative diagnoses involving the upper gastrointestinal tract, such as refractory ischemic gastric or duodenal ulcers.

Mesenteric duplex ultrasound

Particularly useful if obstruction is proximal in the mesenteric vessels, but ultrasound cannot assess distal mesenteric blood vessel flow and nonocclusive etiology of ischemia.[12] This is mostly used in vascular units for the assessment of chronic mesenteric ischemia, and is the first-line investigation of choice.[40]

Ultrasound of the bowel can be used to diagnose ischemic colitis (providing the user has adequate expertise) and differentiate between left- and right-sided disease.[41] It is an alternative for patients unable to tolerate contrast media.[35] However, it is not considered a routine investigation and should only be performed by a radiologist with sufficient ultrasound expertise.

How to take a venous blood sample from the antecubital fossa using a vacuum needle.

How to record an ECG. Demonstrates placement of chest and limb electrodes.

Emerging tests

One meta-analysis of studies in newborns, which assessed the use of abdominal near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) as a marker of bowel ischemia in newborns, showed that NIRS accurately detects local tissue oxygenation mismatch, and can be used to monitor gastrointestinal oxygenation and detect bowel ischemia in this patient group.[43] Low gastrointestinal regional blood flow was consistently associated with bowel ischemia.[43] Further investigation is needed to confirm the utility of NIRS as a biomarker for bowel ischemia in adults.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer