Approach

TTP is a clinical diagnosis that should be made with the help of a physician trained in hematology. There is no pathognomic laboratory test finding, and the diagnosis is made through a combination of factors. In the era before effective plasma exchange was available, the vast majority of patients developed five characteristic clinical features (a pentad) that characterize the disease:

Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia

Thrombocytopenia with purpura

Acute renal insufficiency (classically less marked in TTP than in hemolytic uremic syndrome)

Neurologic abnormalities (classically more marked in TTP than in hemolytic uremic syndrome)

Fever.

With the advent of effective treatment, it is rare for all of these features to be seen, and the diagnosis should be suspected in any patient with thrombocytopenia and microangiopathic hemolytic anemia. Prompt diagnosis is essential so that treatment can be started as early as possible, and an urgent hematology consultation should be obtained as soon as the diagnosis is suspected.

History and exam

Most patients present between the ages of 30 and 50 years. There is usually a nonspecific prodrome, which is followed by the onset of components of the pentad. Neurologic manifestations are present in most patients, and range from subtle changes, such as confusion and severe headache, to focal neurologic abnormalities (similar to stroke or transient ischemic attacks), seizures, and coma. Fever may be present in some patients, but the presence of chills and a high spiking fever should prompt suspicion of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) or sepsis. Some patients also complain of weakness. Gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain may be present secondary to microthrombi in the bowel. However, diarrhea may also be related to Escherichia coli infection, suggesting the diagnosis of hemolytic uremic syndrome rather than TTP. Purpura, ecchymosis, and menorrhagia due to thrombocytopenia may also be seen in 20% of cases.

A history of pregnancy may be present; pregnancy may be the cause of TTP, but may also suggest preeclampsia, eclampsia, or hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count (HELLP) syndrome, which should be excluded. A careful drug history should be taken to identify both known causes of TTP (chemotherapy agents, antiplatelet agents, quinine) and causes of isolated thrombocytopenia.

Clinical exam may reveal focal neurologic signs or signs of bleeding such as purpura and ecchymosis. Blood pressure should be measured and is normal; elevated blood pressure should prompt suspicion of malignant hypertension (if the elevation is marked), or preeclampsia, eclampsia, or HELLP syndrome (if the patient is pregnant).

Tests

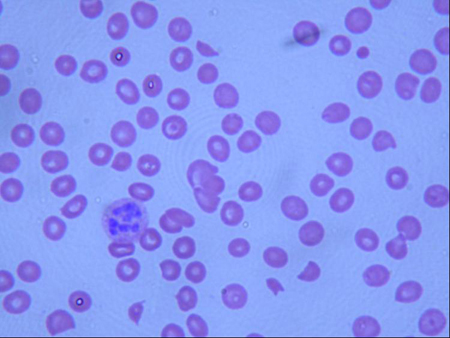

A complete blood count will confirm anemia and thrombocytopenia in the absence of leukopenia. The degree of thrombocytopenia varies, but decreased platelets are required for the diagnosis of TTP. A platelet count of <20 x 10⁹/L is present in approximately 95% of patients. The peripheral smear shows microangiopathic hemolysis as evidenced by the presence of schistocytes.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Peripheral smear of a patient with TTP showing many fragmented, partly rounded cells. Also note the lack of plateletsFrom the collection of Dr R.F. Connor, Harvard Medical School, Boston [Citation ends]. The reticulocyte count is generally elevated. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and bilirubin are often elevated as markers of hemolysis, and LDH is also useful for monitoring the response to treatment.[40] Coagulation studies should be normal, although D-dimer levels are very often increased. Direct Coombs test should be negative to rule out autoimmune hemolytic anemia. BUN and creatinine are typically elevated, reflecting renal dysfunction. Although the renal dysfunction is classically less marked than that seen in hemolytic uremic syndrome, severe renal failure occurs in approximately 5% of patients with TTP. Urinalysis may reveal proteinuria.

The reticulocyte count is generally elevated. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and bilirubin are often elevated as markers of hemolysis, and LDH is also useful for monitoring the response to treatment.[40] Coagulation studies should be normal, although D-dimer levels are very often increased. Direct Coombs test should be negative to rule out autoimmune hemolytic anemia. BUN and creatinine are typically elevated, reflecting renal dysfunction. Although the renal dysfunction is classically less marked than that seen in hemolytic uremic syndrome, severe renal failure occurs in approximately 5% of patients with TTP. Urinalysis may reveal proteinuria.

Assays have been developed to measure von Willebrand factor cleaving enzyme (ADAMTS-13) activity. A common ADAMTS-13 assay based on fluorescence energy transfer detecting VWF cleavage products (FRETS-VWF73) is calibrated against the World Health Organization’s International Standard for ADAMTS-13 in plasma.[41][42]

ADAMTS-13 activity can be low, and ADAMTS-13 inhibitors can often be demonstrated in patients with TTP. These are confirmatory tests, as the results are not returned in time to make a prompt diagnosis. There is debate over whether the ADAMTS-13 activity assay can help in the management of patients with TTP. It does not appear to predict who will respond to plasma exchange. Studies have shown that the multiple domains of ADAMTS-13 are frequently targeted by anti-ADAMTS-13 immunoglobulins (inhibitors) in patients with acquired (idiopathic) TTP. Immunosuppression could work by reducing this inhibitor.[43]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer