Nonbilious projectile post-feeding emesis in a 2- to 12-week-old infant with a palpable pylorus is pathognomonic for pyloric stenosis. Ultrasound is commonly used in cases where a palpable pylorus is not initially appreciated.

History

Parents typically report a history of progressive nonbilious vomiting after feeding. There may be a history of formula changes without resolution of symptoms. Gastroesophageal reflux may have been tentatively diagnosed.

The infant may also have poor weight gain, constipation, or symptoms of volume depletion (e.g., decreased wet diapers).

The incidence is four times greater in male infants than in female infants.[19]Rasmussen L, Green A, Hansen LP. The epidemiology of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in a Danish population, 1950-84. Int J Epidemiol. 1989 Jun;18(2):413-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2767855?tool=bestpractice.com

The disease is also associated with a non-Mendelian familial pattern.[17]Schechter R, Torfs CP, Bateson TF. The epidemiology of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 1997 Oct;11(4):407-27.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9373863?tool=bestpractice.com

[19]Rasmussen L, Green A, Hansen LP. The epidemiology of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in a Danish population, 1950-84. Int J Epidemiol. 1989 Jun;18(2):413-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2767855?tool=bestpractice.com

[33]MacMahon B. The continuing enigma of pyloric stenosis of infancy: a review. Epidemiology. 2006 Mar;17(2):195-201.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16477261?tool=bestpractice.com

The diagnosis of pyloric stenosis in premature infants may be challenging as they present at a later chronological age (40 days vs. 33 days in full-term infants), but at an earlier postmenstrual age (42 weeks vs. 45 weeks in full-term infants), than full-term infants.[24]Stark CM, Rogers PL, Eberly MD, et al. Association of prematurity with the development of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Pediatr Res. 2015 Aug;78(2):218-22.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25950452?tool=bestpractice.com

One retrospective study demonstrated that a greater degree of prematurity was associated with older chronological age at presentation; the authors concluded that pyloric stenosis is likely to present at a postconceptional age of 44 to 50 weeks in both term and preterm infants.[42]Costanzo CM, Vinocur C, Berman L. Prematurity affects age of presentation of pyloric stenosis. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2016 Jul 20;56(2):127-31.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27149987?tool=bestpractice.com

Exam

If the presenting history is suggestive, palpation of an olive-shaped upper abdominal mass (often known as an "olive") confirms the diagnosis. The mass, which is the hypertrophied pyloric muscle, can be palpated in the epigastrium and right upper quadrant. Usually the infant is not calm and is crying; therefore, patience and experience are of utmost importance. The examination is aided by the placement of an orogastric tube for gastric decompression followed by sham feeding with a pacifier dipped in formula or glucose water. The examination should reveal a firm, mobile mass inferior to the liver edge.

The infant may also show peristaltic waves traveling from left to right across the abdomen on examination. This is due to the stomach attempting to force its contents past the narrowed pyloric outlet. Signs of volume depletion may be present, such as dry mucous membranes, flat or depressed fontanelles, or tachycardia.

Physical examination has a sensitivity of 74% to 79%.[43]Forman HP, Leonidas JC, Kronfeld GD. A rational approach to the diagnosis of hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: do the results match the claims? J Pediatr Surg. 1990 Feb;25(2):262-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2406409?tool=bestpractice.com

[44]White MC, Langer JC, Don S, et al. Sensitivity and cost minimization analysis of radiology versus olive palpation for the diagnosis of hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. J Pediatr Surg. 1998 Jun;33(6):913-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9660228?tool=bestpractice.com

[45]Hulka F, Campbell TJ, Campbell JR, et al. Evolution in the recognition of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Pediatrics. 1997 Aug;100(2):E9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9233980?tool=bestpractice.com

There is a decreasing trend in physicians diagnosing this condition based on physical examination because of the availability of imaging, and ultrasound evaluation has become standard practice in many facilities.[46]Macdessi J, Oates RK. Clinical diagnosis of pyloric stenosis: a declining art. BMJ. 1993 Feb 27;306(6877):553-5.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1677170/pdf/bmj00009-0027.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8461768?tool=bestpractice.com

[47]Poon TS, Zhang AL, Cartmill T, et al. Changing patterns of diagnosis and treatment of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: a clinical audit of 303 patients. J Pediatr Surg. 1996 Dec;31(12):1611-5.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8986971?tool=bestpractice.com

Laboratory evaluation

An electrolyte panel should be ordered in all suspected cases; common findings include hypokalemia, hypochloremia, and metabolic alkalosis as a result of prolonged vomiting. The degree of electrolyte abnormalities depends on the duration of symptoms prior to presentation.[48]Touloukian RJ, Higgins E. The spectrum of serum electrolytes in hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. J Pediatr Surg. 1983 Aug;18(4):394-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6620080?tool=bestpractice.com

Due to earlier diagnosis, fewer infants present with classical findings.[45]Hulka F, Campbell TJ, Campbell JR, et al. Evolution in the recognition of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Pediatrics. 1997 Aug;100(2):E9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9233980?tool=bestpractice.com

Imaging

Ultrasonography is the most commonly employed investigation for diagnosis.[49]Expert Panel on Pediatric Imaging., Alazraki AL, Rigsby CK, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Vomiting in infants. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020 Nov;17(11s):S505-S515.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2020.09.002

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33153561?tool=bestpractice.com

The sensitivity of ultrasound in diagnosing pyloric stenosis is reported to be 97% to 99%.[5]Stunden RJ, LeQuesne GW, Little K. The improved ultrasound diagnosis of hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Pediatr Radiol. 1986;16(3):200-5.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3517794?tool=bestpractice.com

[8]Neilson D, Hollman AS. The ultrasonic diagnosis of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: technique and accuracy. Clin Radiol. 1994 Apr;49(4):246-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8162680?tool=bestpractice.com

[50]Hernanz-Schulman M, Sells LL, Ambrosino MM, et al. Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in the infant without a palpable olive: accuracy of sonographic diagnosis. Radiology. 1994 Dec;193(3):771-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7972822?tool=bestpractice.com

[51]Tunell WP, Wilson DA. Pyloric stenosis: diagnosis by real time sonography, the pyloric muscle length method. J Pediatr Surg. 1984 Dec;19(6):795-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6394734?tool=bestpractice.com

[52]Iqbal CW, Rivard DC, Mortellaro VE, et al. Evaluation of ultrasonographic parameters in the diagnosis of pyloric stenosis relative to patient age and size. J Pediatr Surg. 2012 Aug;47(8):1542-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22901914?tool=bestpractice.com

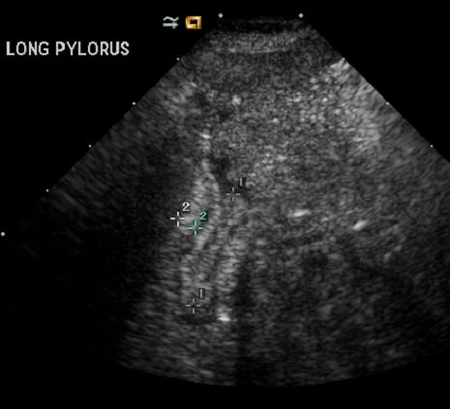

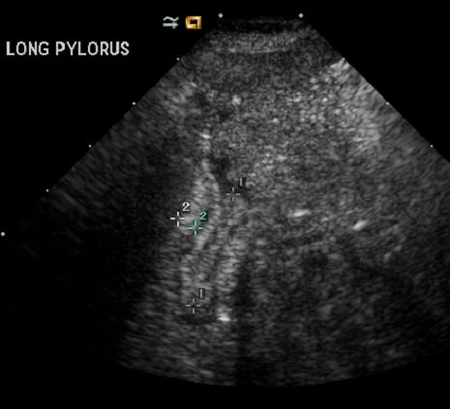

Pyloric muscle thickness >3 mm and pyloric canal length >15 mm meet the diagnostic criteria for full-term infants.[11]Said M, Shaul DB, Fujimoto M, et al. Ultrasound measurements in hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: don't let the numbers fool you. Perm J. 2012 Summer;16(3):25-7.

https://www.doi.org/10.7812/TPP/12.966

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23012595?tool=bestpractice.com

[53]Rohrschneider WK, Mittnacht H, Darge K, et al. Pyloric muscle in asymptomatic infants: sonographic evaluation and discrimination from idiopathic hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Pediatr Radiol. 1998 Jun;28(6):429-34.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9634457?tool=bestpractice.com

Ultrasound also allows real-time examination of pyloric channel function. Patients will have abnormal flow and peristalsis.

Upper GI contrast investigations have been described in the diagnosis of pyloric stenosis. A positive upper GI contrast observation shows a thin strand of contrast (a string sign) as a result of a narrow pylorus. However, it may lead to further vomiting and increase the risk of aspiration. Due to this increased risk, it is not a recommended method for the diagnosis of pyloric stenosis.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Pyloric ultrasound. <1> interval: length; <2> interval: muscle widthFrom the collection of Dr Jeffrey S. Upperman; used with permission [Citation ends].