Acute pancreatitis has two distinct phases that require different management approaches: the early phase (1 week), characterized by systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and/or organ failure and the late phase (>1 week), characterized by local complications including sterile or infected pancreatic necrosis and pseudocysts.[8]Tenner S, Vege S, Sheth S, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Mar 119(3):419-37.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/fulltext/2024/03000/american_college_of_gastroenterology_guidelines_.14.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38857482?tool=bestpractice.com

In most patients, the disease is mild and improves rapidly within 3-7 days with fluid resuscitation, management of pain and nausea, and early oral feeding, while around 20% to 30% of patients develop severe disease, with a hospital mortality rate of around 15%.[28]Leppäniemi A, Tolonen M, Tarasconi A, et al. 2019 WSES guidelines for the management of severe acute pancreatitis. World J Emerg Surg. 2019 Jun 13;14:27.

https://wjes.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13017-019-0247-0

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31210778?tool=bestpractice.com

Initial management

All patients need to be treated with intravenous hydration for the first 24 hours and monitored closely for early fluid losses, hypovolemic shock, and symptoms suggestive of organ dysfunction in the first 48-72 hours from presentation.[8]Tenner S, Vege S, Sheth S, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Mar 119(3):419-37.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/fulltext/2024/03000/american_college_of_gastroenterology_guidelines_.14.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38857482?tool=bestpractice.com

[71]de-Madaria E, Buxbaum JL, Maisonneuve P, et al. Aggressive or moderate fluid resuscitation in acute pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2022 Sep 15;387(11):989-1000.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36103415?tool=bestpractice.com

A steady rate of initial resuscitation is recommended, with close monitoring and addition of a fluid bolus only if there is evidence of hypovolemia.[71]de-Madaria E, Buxbaum JL, Maisonneuve P, et al. Aggressive or moderate fluid resuscitation in acute pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2022 Sep 15;387(11):989-1000.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36103415?tool=bestpractice.com

[72]Gardner TB. Fluid resuscitation in acute pancreatitis: going over the WATERFALL. N Engl J Med. 2022 Sep 15;387(11):1038-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36103418?tool=bestpractice.com

Clinicians should recognize that patients with acute pancreatitis may develop hypovolemia rapidly after admission and require fluid boluses and/or increases in the rate of hydration.[8]Tenner S, Vege S, Sheth S, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Mar 119(3):419-37.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/fulltext/2024/03000/american_college_of_gastroenterology_guidelines_.14.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38857482?tool=bestpractice.com

Previously, aggressive early rehydration was recommended for all patients with acute pancreatitis but evidence now supports a moderate approach with close attention to vital signs, especially heart rate, with BUN and hematocrit evaluation at frequent intervals (within 6 hours of presentation and for the following 24-48 hours).[8]Tenner S, Vege S, Sheth S, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Mar 119(3):419-37.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/fulltext/2024/03000/american_college_of_gastroenterology_guidelines_.14.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38857482?tool=bestpractice.com

[71]de-Madaria E, Buxbaum JL, Maisonneuve P, et al. Aggressive or moderate fluid resuscitation in acute pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2022 Sep 15;387(11):989-1000.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36103415?tool=bestpractice.com

[73]Li XW, Wang CH, Dai JW, et al. Comparison of clinical outcomes between aggressive and non-aggressive intravenous hydration for acute pancreatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2023 Mar 22;27(1):122.

https://www.doi.org/10.1186/s13054-023-04401-0

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36949459?tool=bestpractice.com

It may not be possible to predict which patients with acute pancreatitis will develop severe disease: severity scoring tools such as APACHE II and Glasgow have limited value early in the course of the disease. While early laboratory testing of hematocrit and renal function is important to determine intravascular fluid losses and early renal insufficiency, no laboratory test has been shown to be consistently accurate in predicting later disease severity.[8]Tenner S, Vege S, Sheth S, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Mar 119(3):419-37.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/fulltext/2024/03000/american_college_of_gastroenterology_guidelines_.14.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38857482?tool=bestpractice.com

[74]Baillie J, ed. Advances in endoscopy: current developments in diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopy. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2010 Jan;6(1):16-8.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2886440

No patient should be classified as having mild disease until at least 48 hours after symptom onset, as some patients who go on to develop severe disease present without signs of organ failure or local complications.[8]Tenner S, Vege S, Sheth S, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Mar 119(3):419-37.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/fulltext/2024/03000/american_college_of_gastroenterology_guidelines_.14.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38857482?tool=bestpractice.com

It is critical to recognize the importance of organ failure in determining disease severity.[8]Tenner S, Vege S, Sheth S, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Mar 119(3):419-37.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/fulltext/2024/03000/american_college_of_gastroenterology_guidelines_.14.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38857482?tool=bestpractice.com

In the presence of SIRS-associated organ dysfunction, additional monitoring and organ support may be necessary (e.g., oxygen supplementation and/or ventilatory support for respiratory failure). Signs of cardiovascular, respiratory, or renal dysfunction may be present. Patients with organ failure and/or persisting SIRS should be admitted to an intensive care unit whenever possible.[8]Tenner S, Vege S, Sheth S, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Mar 119(3):419-37.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/fulltext/2024/03000/american_college_of_gastroenterology_guidelines_.14.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38857482?tool=bestpractice.com

[28]Leppäniemi A, Tolonen M, Tarasconi A, et al. 2019 WSES guidelines for the management of severe acute pancreatitis. World J Emerg Surg. 2019 Jun 13;14:27.

https://wjes.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13017-019-0247-0

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31210778?tool=bestpractice.com

The definition of SIRS is met by the presence of at least two of the following criteria:[49]Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, et al. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS international sepsis definitions conference. Crit Care Med. 2003 Apr;31(4):1250-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12682500?tool=bestpractice.com

Pulse >90 beats per minute

Respiratory rate >20 per minute or partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO₂) <32 mmHg

Temperature >100.4°F or <96.8ºF

WBC count >12,000 or <4000 cells/mm³, or >10% immature neutrophils (bands)

The presence of persistent (>48 hours) single- or multi-organ failure defines acute pancreatitis as severe according to the revised Atlanta criteria.[8]Tenner S, Vege S, Sheth S, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Mar 119(3):419-37.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/fulltext/2024/03000/american_college_of_gastroenterology_guidelines_.14.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38857482?tool=bestpractice.com

[28]Leppäniemi A, Tolonen M, Tarasconi A, et al. 2019 WSES guidelines for the management of severe acute pancreatitis. World J Emerg Surg. 2019 Jun 13;14:27.

https://wjes.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13017-019-0247-0

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31210778?tool=bestpractice.com

In everyday clinical practice, the following criteria (original Atlanta criteria) may be used to establish organ failure:[8]Tenner S, Vege S, Sheth S, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Mar 119(3):419-37.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/fulltext/2024/03000/american_college_of_gastroenterology_guidelines_.14.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38857482?tool=bestpractice.com

Shock: systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg

Pulmonary insufficiency: partial pressure of oxygen (PaO₂) ≤60%

Renal failure: creatinine >2 mg/dL

Gastrointestinal bleeding: >500 mL blood loss in 24 hours

Early intravenous hydration

The initial treatment of acute pancreatitis requires early intravenous hydration.[1]Nirula R. Chapter 9: Diseases of the pancreas. High yield surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000.[5]Way LW, Doherty GM. Chapter 27: Pancreas. In: Current surgical diagnosis & treatment. 11th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2003.[71]de-Madaria E, Buxbaum JL, Maisonneuve P, et al. Aggressive or moderate fluid resuscitation in acute pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2022 Sep 15;387(11):989-1000.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36103415?tool=bestpractice.com

[75]Darvas K, Futo J, Okros I, et al. Principles of intensive care in severe acute pancreatitis in 2008 [in Hungarian]. Orv Hetil. 2008 Nov 23;149(47):2211-20.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19004743?tool=bestpractice.com

[76]Curtis CS, Kudsk KA. Nutrition support in pancreatitis. Surg Clin North Am. 2007 Dec;87(6):1403-15.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18053838?tool=bestpractice.com

[77]Thomson A. Nutritional support in acute pancreatitis. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2008 May;11(3):261-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18403922?tool=bestpractice.com

[78]Marik PE. What is the best way to feed patients with pancreatitis? Curr Opin Crit Care. 2009 Apr;15(2):131-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19300086?tool=bestpractice.com

[79]Kumari R, Sadarat F, Luhana S, et al. Evaluating the efficacy of different volume resuscitation strategies in acute pancreatitis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2024 Mar 25;24(1):119.

https://www.doi.org/10.1186/s12876-024-03205-y

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38528470?tool=bestpractice.com

Clinicians should focus on a steady rate of initial resuscitation (no more than 1.5 mL/kg/hour) and should administer a bolus of 10 mL/kg only if there are signs of hypovolemia.[72]Gardner TB. Fluid resuscitation in acute pancreatitis: going over the WATERFALL. N Engl J Med. 2022 Sep 15;387(11):1038-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36103418?tool=bestpractice.com

A balanced crystalloid (such as Ringer's lactate [Hartmann solution] or Plasma-Lyte®) may have benefits compared with normal saline, and guidelines generally recommend use of a balanced crystalloid for patients with acute pancreatitis.[8]Tenner S, Vege S, Sheth S, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Mar 119(3):419-37.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/fulltext/2024/03000/american_college_of_gastroenterology_guidelines_.14.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38857482?tool=bestpractice.com

[28]Leppäniemi A, Tolonen M, Tarasconi A, et al. 2019 WSES guidelines for the management of severe acute pancreatitis. World J Emerg Surg. 2019 Jun 13;14:27.

https://wjes.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13017-019-0247-0

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31210778?tool=bestpractice.com

[46]Wu D, Wan J, Xia L, et al. The efficiency of aggressive hydration with lactated ringer solution for the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017 Sep;51(8):e68-76.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28609383?tool=bestpractice.com

[47]Working Group IAP/APA Acute Pancreatitis Guidelines. IAP/APA evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2013 Jul-Aug;13(4 Suppl 2):e1-15.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1424390313005255?via%3Dihub

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24054878?tool=bestpractice.com

[80]Choosakul S, Harinwan K, Chirapongsathorn S, et al. Comparison of normal saline versus Lactated Ringer's solution for fluid resuscitation in patients with mild acute pancreatitis, a randomized controlled trial. Pancreatology. 2018 Jul;18(5):507-12.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29754857?tool=bestpractice.com

[81]Hong J, Li Q, Wang Y, et al. Comparison of fluid resuscitation with lactate ringer's versus normal saline in acute pancreatitis: an updated meta-analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2024 Jan;69(1):262-74.

https://www.doi.org/10.1007/s10620-023-08187-7

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38015322?tool=bestpractice.com

Normal saline given in large volumes may lead to the development of a non-anion gap hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis.[8]Tenner S, Vege S, Sheth S, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Mar 119(3):419-37.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/fulltext/2024/03000/american_college_of_gastroenterology_guidelines_.14.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38857482?tool=bestpractice.com

This has particular relevance in acute pancreatitis where low pH may trigger premature trypsinogen activation and exacerbate the symptom of abdominal pain. However, high-quality evidence on choice of fluid specific to patients with acute pancreatitis is lacking, and results from randomized controlled trials of critically unwell patients in general (not specifically people with acute pancreatitis) have reached conflicting conclusions.[82]Semler MW, Self WH, Wanderer JP, et al. Balanced crystalloids versus saline in critically ill adults. N Engl J Med. 2018 Mar 1;378(9):829-39.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa1711584

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29485925?tool=bestpractice.com

[83]Zampieri FG, Machado FR, Biondi RS, et al. Effect of intravenous fluid treatment with a balanced solution vs 0.9% saline solution on mortality in critically ill patients: the BaSICS randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021 Aug 10;326(9):1-12.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2783039

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34375394?tool=bestpractice.com

[84]Finfer S, Micallef S, Hammond N, et al. Balanced multielectrolyte solution versus saline in critically ill adults. N Engl J Med. 2022 Mar 3;386(9):815-26.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35041780?tool=bestpractice.com

A rising blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and/or hematocrit in the first 24-48 hours indicates inadequate rehydration and has been associated with the risk of developing organ failure and pancreatic necrosis. Rapid intravenous hydration sufficient to decrease hematocrit (i.e., hemodilution) and/or BUN (i.e., increased renal perfusion) has been shown to decrease morbidity and mortality.[8]Tenner S, Vege S, Sheth S, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Mar 119(3):419-37.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/fulltext/2024/03000/american_college_of_gastroenterology_guidelines_.14.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38857482?tool=bestpractice.com

[56]Brown A, Orav J, Banks PA. Hemoconcentration is an early marker for organ failure and necrotizing pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2000 May;20(4):367-72.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10824690?tool=bestpractice.com

[85]Crockett SD, Wani S, Gardner TB, et al. American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on initial management of acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2018 Mar;154(4):1096-101.

https://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(18)30076-3/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29409760?tool=bestpractice.com

Studies have shown that these benefits appear at 24 hours.[86]Buxbaum JL, Quezada M, Da B, et al. Early aggressive hydration hastens clinical improvement in mild acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 May;112(5):797-803.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28266591?tool=bestpractice.com

[87]Fisher JM, Gardner TB. The "golden hours" of management in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012 Aug;107(8):1146-50.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22858994?tool=bestpractice.com

Measurement of BUN and hematocrit within 6-8 hours of admission is therefore recommended so that timely adjustments in the rate of hydration can be made.[8]Tenner S, Vege S, Sheth S, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Mar 119(3):419-37.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/fulltext/2024/03000/american_college_of_gastroenterology_guidelines_.14.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38857482?tool=bestpractice.com

Conversely, close observation of clinical parameters such as heart rate, blood pressure, and urine output is needed to guard against the risk of excessive intravenous hydration, particularly in certain patient groups such as older individuals and those with a history of cardiac and/or renal disease.[8]Tenner S, Vege S, Sheth S, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Mar 119(3):419-37.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/fulltext/2024/03000/american_college_of_gastroenterology_guidelines_.14.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38857482?tool=bestpractice.com

Large volume resuscitation may worsen third-space losses characteristic of acute pancreatitis, worsening pulmonary edema and/or leading to abdominal compartment syndrome.[8]Tenner S, Vege S, Sheth S, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Mar 119(3):419-37.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/fulltext/2024/03000/american_college_of_gastroenterology_guidelines_.14.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38857482?tool=bestpractice.com

One multicenter randomized controlled trial published in 2022 showed that aggressive early hydration resulted in a higher incidence of fluid overload compared with moderate hydration, without improvement in clinical outcomes.[71]de-Madaria E, Buxbaum JL, Maisonneuve P, et al. Aggressive or moderate fluid resuscitation in acute pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2022 Sep 15;387(11):989-1000.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36103415?tool=bestpractice.com

The rationale for early hydration arises from multiple factors causing hypovolemia including vomiting, reduced oral intake, "third spacing" of fluids, increased respiratory losses, and diaphoresis. A combination of microangiopathic effects and edema in the inflamed pancreas may impede blood flow, leading to increased cellular death, tissue necrosis, and ongoing release of pancreatic enzymes, further activating inflammatory cascades. Inflammation increases vascular permeability leading to increased third-space fluid losses, and worsening pancreatic hypoperfusion. Hypoperfusion of the pancreas leads to further necrosis. Early intravenous fluid resuscitation provides micro- and macrocirculatory support to prevent pancreatic necrosis and reduce the risk of other serious complications.[85]Crockett SD, Wani S, Gardner TB, et al. American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on initial management of acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2018 Mar;154(4):1096-101.

https://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(18)30076-3/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29409760?tool=bestpractice.com

Gallstone pancreatitis

Patients with mild gallstone pancreatitis should have a cholecystectomy during the initial admission, after the acute symptoms have resolved. Cholecystectomy is typically delayed for patients with severe disease; these patients require complex decision-making between the surgeon and gastroenterologist.[8]Tenner S, Vege S, Sheth S, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Mar 119(3):419-37.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/fulltext/2024/03000/american_college_of_gastroenterology_guidelines_.14.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38857482?tool=bestpractice.com

[47]Working Group IAP/APA Acute Pancreatitis Guidelines. IAP/APA evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2013 Jul-Aug;13(4 Suppl 2):e1-15.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1424390313005255?via%3Dihub

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24054878?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients with gallstone pancreatitis complicated by concurrent cholangitis benefit from early endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). The benefit is seen in patients with sepsis and organ failure who undergo the procedure within the first 24 hours from admission.[8]Tenner S, Vege S, Sheth S, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Mar 119(3):419-37.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/fulltext/2024/03000/american_college_of_gastroenterology_guidelines_.14.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38857482?tool=bestpractice.com

[47]Working Group IAP/APA Acute Pancreatitis Guidelines. IAP/APA evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2013 Jul-Aug;13(4 Suppl 2):e1-15.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1424390313005255?via%3Dihub

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24054878?tool=bestpractice.com

[88]van Dijk SM, Hallensleben NDL, van Santvoort HC, et al. Acute pancreatitis: recent advances through randomised trials. Gut. 2017 Nov;66(11):2024-32.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28838972?tool=bestpractice.com

[89]Moretti A, Papi C, Aratari A, et al. Is early endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography useful in the management of acute biliary pancreatitis? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Dig Liver Dis. 2008 May;40(5):379-85.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18243826?tool=bestpractice.com

Although gallstones in the common bile duct are a common cause of acute pancreatitis, most gallstones readily pass to the duodenum and are lost in the stool. Persistent choledocholithiasis can lead to persistent pancreatic duct and/or biliary tree obstruction, leading to necrosis and/or cholangitis. Removal of obstructing gallstones from the biliary tree in patients with acute pancreatitis should reduce the likelihood of complications.

Cholangitis should be suspected in the presence of the Charcot triad (jaundice, fever and rigors, right upper quadrant pain). ERCP is not indicated for either mild or severe gallstone pancreatitis without cholangitis.[64]Fogel EL, Sherman S. ERCP for gallstone pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2014 Jan 9;370(2):150-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24401052?tool=bestpractice.com

[85]Crockett SD, Wani S, Gardner TB, et al. American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on initial management of acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2018 Mar;154(4):1096-101.

https://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(18)30076-3/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29409760?tool=bestpractice.com

The risks of the procedure outweigh any potential benefits in this patient population.

Analgesia and antiemesis

Pain control with opioids may reduce the need for multimodal analgesia.[90]Basurto Ona X, Rigau Comas D, Urrútia G. Opioids for acute pancreatitis pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Jul 26;(7):CD009179.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD009179.pub2/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23888429?tool=bestpractice.com

[  ]

How do opioids compare with non-opioid analgesics for the management of acute pancreatitis pain?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.515/fullShow me the answer[Evidence C]d882442b-b363-4620-b29d-252a65d97c79ccaCHow do opioids compare with nonopioid analgesics for the management of acute pancreatitis pain?

]

How do opioids compare with non-opioid analgesics for the management of acute pancreatitis pain?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.515/fullShow me the answer[Evidence C]d882442b-b363-4620-b29d-252a65d97c79ccaCHow do opioids compare with nonopioid analgesics for the management of acute pancreatitis pain?

Fentanyl or morphine can be used, either for breakthrough pain or as patient-controlled analgesia. In mild cases, the standard World Health Organization pain ladder can be used to inform the selection, monitoring, and adjustment of analgesia. Ketorolac, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, can be used in patients with intact renal function. It should not be used in older patients because of the risk of adverse gastrointestinal effects.[91]American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012 Apr;60(4):616-31.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3571677

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22376048?tool=bestpractice.com

Nausea and/or vomiting is a presenting symptom in 70% to 80% of patients. Ondansetron is the most commonly used antiemetic.

Nutrition

Nutrition in mild to moderate acute pancreatitis

In mild acute pancreatitis, oral intake should be restored quickly and usually no nutritional intervention is needed. Although the timing of refeeding remains controversial, recent studies have shown that immediate oral feeding in patients with mild disease appears safe.[92]Ramírez-Maldonado E, López Gordo S, Pueyo EM, et al. Immediate oral refeeding in patients with mild and moderate acute pancreatitis: a multicenter, randomized controlled trial (PADI trial). Ann Surg. 2021 Aug 1;274(2):255-63.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33196485?tool=bestpractice.com

Both the American College of Gastroenterology and the American Gastroenterological Association recommend oral feeding within 24 hours, if tolerated, in patients with acute pancreatitis.[8]Tenner S, Vege S, Sheth S, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Mar 119(3):419-37.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/fulltext/2024/03000/american_college_of_gastroenterology_guidelines_.14.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38857482?tool=bestpractice.com

[85]Crockett SD, Wani S, Gardner TB, et al. American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on initial management of acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2018 Mar;154(4):1096-101.

https://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(18)30076-3/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29409760?tool=bestpractice.com

Earlier guidelines had recommended withholding oral feeding ("pancreatic rest") until resolution of pain and/or normalization of pancreatic enzymes or evidence of resolution of inflammation from imaging. However, current evidence shows early oral feeding leads to better outcomes.[93]Vaughn VM, Shuster D, Rogers MAM, et al. Early versus delayed feeding in patients with acute pancreatitis: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2017 Jun 20;166(12):883-92.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28505667?tool=bestpractice.com

[94]Bakker OJ, van Brunschot S, van Santvoort HC, et al. Early versus on-demand nasoenteric tube feeding in acute pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2014 Nov 20;371(21):1983-93.

http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1404393#t=article

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25409371?tool=bestpractice.com

[95]Liang XY, Wu XA, Tian Y, et al. Effects of early versus delayed feeding in patients with acute pancreatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2024 May-Jun 01;58(5):522-30.

https://www.doi.org/10.1097/MCG.0000000000001886

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37428071?tool=bestpractice.com

One systematic review of 11 randomized studies showed no association between early feeding (≤48 hours after hospitalization; studies assessed oral, nasogastric, and nasojejunal routes) and increased risk of adverse events compared with delayed feeding; and patients with mild to moderate pancreatitis receiving early feeding benefited from a reduced length of hospital stay.[93]Vaughn VM, Shuster D, Rogers MAM, et al. Early versus delayed feeding in patients with acute pancreatitis: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2017 Jun 20;166(12):883-92.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28505667?tool=bestpractice.com

Nutrition in severe acute pancreatitis

In patients who are unable to feed orally, enteral tube nutrition should be used; parenteral nutrition should be avoided.[96]Arvanitakis M, Ockenga J, Bezmarevic M, et al. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition in acute and chronic pancreatitis. Clin Nutr. 2020 Mar;39(3):612-31.

https://www.clinicalnutritionjournal.com/article/S0261-5614(20)30009-1/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32008871?tool=bestpractice.com

There have been multiple randomized trials showing that total parenteral nutrition is associated with infectious and other line-related complications. Enteral feeding maintains the gut mucosal barrier, prevents disruption, and prevents the translocation of bacteria to seed pancreatic necrosis.[97]Yi F, Ge L, Zhao J, et al. Meta-analysis: total parenteral nutrition versus total enteral nutrition in predicted severe acute pancreatitis. Intern Med. 2012;51(6):523-30.

https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/internalmedicine/51/6/51_6_523/_pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22449657?tool=bestpractice.com

[98]Mirtallo JM, Forbes A, McClave SA, et al. International consensus guidelines for nutrition therapy in pancreatitis. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2012 May;36(3):284-91.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22457421?tool=bestpractice.com

[99]Petrov MS, Zagainov V. Influence of enteral versus parenteral nutrition on blood glucose control in acute pancreatitis: a systematic review. Clin Nutr. 2007 Oct;26(5):514-23.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17559987?tool=bestpractice.com

Continuous enteral infusion is preferred over cyclic or bolus administration.[8]Tenner S, Vege S, Sheth S, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Mar 119(3):419-37.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/fulltext/2024/03000/american_college_of_gastroenterology_guidelines_.14.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38857482?tool=bestpractice.com

Small peptide-based medium chain triglyceride formulas can be used if standard formulas are not tolerated.[96]Arvanitakis M, Ockenga J, Bezmarevic M, et al. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition in acute and chronic pancreatitis. Clin Nutr. 2020 Mar;39(3):612-31.

https://www.clinicalnutritionjournal.com/article/S0261-5614(20)30009-1/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32008871?tool=bestpractice.com

Nasogastric tube feeding is recommended in preference to the nasojejunal route for most patients.[8]Tenner S, Vege S, Sheth S, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Mar 119(3):419-37.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/fulltext/2024/03000/american_college_of_gastroenterology_guidelines_.14.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38857482?tool=bestpractice.com

[96]Arvanitakis M, Ockenga J, Bezmarevic M, et al. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition in acute and chronic pancreatitis. Clin Nutr. 2020 Mar;39(3):612-31.

https://www.clinicalnutritionjournal.com/article/S0261-5614(20)30009-1/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32008871?tool=bestpractice.com

One systematic review describing 92 patients from 4 studies on nasogastric tube feeding found that it was safe and well tolerated in patients with predicted severe acute pancreatitis.[100]Petrov MS, Kukosh MV, Emelyanov NV. A randomized controlled trial of enteral versus parenteral feeding in patients with predicted severe acute pancreatitis shows a significant reduction in mortality and in infected pancreatic complications with total enteral nutrition. Dig Surg. 2006;23(5-6):336-44; discussion 344-5.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17164546?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients at increased risk of aspiration should be put in a more upright position and placed on aspiration precautions.[8]Tenner S, Vege S, Sheth S, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Mar 119(3):419-37.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/fulltext/2024/03000/american_college_of_gastroenterology_guidelines_.14.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38857482?tool=bestpractice.com

Nasojejunal tube placement requires interventional radiology or endoscopy and thus has resource implications, but has no proven benefit over nasogastric tube feeding in terms of safety or effectiveness.[8]Tenner S, Vege S, Sheth S, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Mar 119(3):419-37.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/fulltext/2024/03000/american_college_of_gastroenterology_guidelines_.14.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38857482?tool=bestpractice.com

[101]Dutta AK, Goel A, Kirubakaran R, et al. Nasogastric versus nasojejunal tube feeding for severe acute pancreatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020 Mar 26;(3):CD010582.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD010582.pub2/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32216139?tool=bestpractice.com

[102]Hsieh PH, Yang TC, Kang EY, et al. Impact of nutritional support routes on mortality in acute pancreatitis: a network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Intern Med. 2024 Jun;295(6):759-73.

https://www.doi.org/10.1111/joim.13782

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38561603?tool=bestpractice.com

Oral nutrition should resume as soon as pain and any nausea/vomiting begin to subside. A randomized trial showed that an oral diet after 72 hours was just as effective compared with early nasoenteric tube feeding in reducing the rate of infection or death in patients with acute pancreatitis at high risk of complications.[94]Bakker OJ, van Brunschot S, van Santvoort HC, et al. Early versus on-demand nasoenteric tube feeding in acute pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2014 Nov 20;371(21):1983-93.

http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1404393#t=article

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25409371?tool=bestpractice.com

No specific enteral nutrition formulation has been proven to be better than another in patients with acute pancreatitis.[103]Poropat G, Giljaca V, Hauser G, et al. Enteral nutrition formulations for acute pancreatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Mar 23;(3):CD010605.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD010605.pub2/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25803695?tool=bestpractice.com

Infectious complications

Many patients with acute pancreatitis who develop severe disease have infectious complications, including cholangitis, urinary tract infections, infected pseudocysts, fluid collections, and infected pancreatic necrosis. Fever, tachycardia, tachypnea, and leukocytosis are associated with the SIRS that may occur early in the course of acute pancreatitis. This clinical picture may be indistinguishable from sepsis. When an infection is suspected, antibiotics should be given while the source of the infection is being investigated. However, once blood and other cultures are found to be negative and no source of infection is identified, antibiotics should be discontinued. Despite the risk of infectious complications, the American College of Gastroenterology and the American Gastroenterology Association recommend against the use of prophylactic antibiotics in patients with severe acute pancreatitis (or predicted severe acute pancreatitis).[8]Tenner S, Vege S, Sheth S, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Mar 119(3):419-37.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/fulltext/2024/03000/american_college_of_gastroenterology_guidelines_.14.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38857482?tool=bestpractice.com

[85]Crockett SD, Wani S, Gardner TB, et al. American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on initial management of acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2018 Mar;154(4):1096-101.

https://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(18)30076-3/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29409760?tool=bestpractice.com

Pancreatic necrosis

In most patients, necrosis is associated with moderately severe or severe disease.[85]Crockett SD, Wani S, Gardner TB, et al. American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on initial management of acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2018 Mar;154(4):1096-101.

https://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(18)30076-3/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29409760?tool=bestpractice.com

Pancreatic necrosis is defined as diffuse or focal areas of nonviable pancreatic parenchyma >3 cm in size or >30% of the pancreas.[8]Tenner S, Vege S, Sheth S, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Mar 119(3):419-37.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/fulltext/2024/03000/american_college_of_gastroenterology_guidelines_.14.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38857482?tool=bestpractice.com

Sterile necrosis

Early in the course of the disease, areas of necrotic pancreas form a diffuse solid/semi-solid inflammatory mass. Endoscopic, surgical, and/or radiologic intervention should be avoided within the first 4 weeks, unless a patient is deteriorating. After approximately 4 weeks, a fibrous wall develops around the necrotic area, making it more amenable to intervention. At this stage, drainage or necrosectomy/debridement may be considered.[47]Working Group IAP/APA Acute Pancreatitis Guidelines. IAP/APA evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2013 Jul-Aug;13(4 Suppl 2):e1-15.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1424390313005255?via%3Dihub

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24054878?tool=bestpractice.com

Prophylactic antibiotics to prevent infection are not recommended for patients with sterile necrosis (even for those predicted as having severe disease).[8]Tenner S, Vege S, Sheth S, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Mar 119(3):419-37.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/fulltext/2024/03000/american_college_of_gastroenterology_guidelines_.14.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38857482?tool=bestpractice.com

Although early unblinded trials suggested that administration of antibiotics may prevent infectious complications in patients with sterile necrosis, subsequent higher-quality trials have consistently failed to confirm an advantage.[8]Tenner S, Vege S, Sheth S, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Mar 119(3):419-37.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/fulltext/2024/03000/american_college_of_gastroenterology_guidelines_.14.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38857482?tool=bestpractice.com

[104]Dellinger EP, Tellado JM, Soto NE, et al. Early antibiotic treatment for severe acute necrotizing pancreatitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Ann Surg. 2007 May;245(5):674-83.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1877078

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17457158?tool=bestpractice.com

One meta-analysis of 11 prospective randomized trials demonstrated that the number-needed-to treat was 1429 for one patient to benefit from the use of prophylactic antibiotics in severe acute pancreatitis.[105]Jiang K, Huang W, Yang XN, et al. Present and future of prophylactic antibiotics for severe acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2012 Jan 21;18(3):279-84.

https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i3/279.htm

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22294832?tool=bestpractice.com

Infected necrosis

Necrotic collections become infected in around one third of patients.[88]van Dijk SM, Hallensleben NDL, van Santvoort HC, et al. Acute pancreatitis: recent advances through randomised trials. Gut. 2017 Nov;66(11):2024-32.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28838972?tool=bestpractice.com

This is thought to occur as a result of bacterial translocation from the gut.[88]van Dijk SM, Hallensleben NDL, van Santvoort HC, et al. Acute pancreatitis: recent advances through randomised trials. Gut. 2017 Nov;66(11):2024-32.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28838972?tool=bestpractice.com

When compared with patients with sterile necrosis, patients with infected pancreatic necrosis have a higher mortality rate (mean 30%, range 14% to 69%).[8]Tenner S, Vege S, Sheth S, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Mar 119(3):419-37.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/fulltext/2024/03000/american_college_of_gastroenterology_guidelines_.14.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38857482?tool=bestpractice.com

Antibiotics should be used judiciously in patients with necrotizing acute pancreatitis if an infection is suspected. Antibiotics with good pancreatic penetration are recommended, such as a carbapenem (e.g., imipenem/cilastatin), a fluoroquinolone (e.g., ciprofloxacin), or metronidazole.[8]Tenner S, Vege S, Sheth S, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Mar 119(3):419-37.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/fulltext/2024/03000/american_college_of_gastroenterology_guidelines_.14.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38857482?tool=bestpractice.com

[28]Leppäniemi A, Tolonen M, Tarasconi A, et al. 2019 WSES guidelines for the management of severe acute pancreatitis. World J Emerg Surg. 2019 Jun 13;14:27.

https://wjes.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13017-019-0247-0

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31210778?tool=bestpractice.com

Systemic fluoroquinolone antibiotics may cause serious, disabling, and potentially long-lasting or irreversible adverse events. This includes, but is not limited to: tendinopathy/tendon rupture; peripheral neuropathy; arthropathy/arthralgia; aortic aneurysm and dissection; heart valve regurgitation; dysglycemia; and central nervous system effects including seizures, depression, psychosis, and suicidal thoughts and behavior.[106]Rusu A, Munteanu AC, Arbănași EM, et al. Overview of side-effects of antibacterial fluoroquinolones: new drugs versus old drugs, a step forward in the safety profile? Pharmaceutics. 2023 Mar 1;15(3):804.

https://www.doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics15030804

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36986665?tool=bestpractice.com

Prescribing restrictions apply to the use of fluoroquinolones, and these restrictions may vary between countries. In general, fluoroquinolones should be restricted for use in serious, life-threatening bacterial infections only. Some regulatory agencies may also recommend that they must only be used in situations where other antibiotics, that are commonly recommended for the infection, are inappropriate (e.g., resistance, contraindications, treatment failure, and unavailability).

Consult your local guidelines and drug information source for more information on suitability, contraindications, and precautions.

Historically, all patients with infected pancreatic necrosis were subject to prompt surgical debridement. This is no longer recommended unless the patient is clinically unstable.[18]Hines OJ, Pandol SJ. Management of severe acute pancreatitis. BMJ. 2019 Dec 2;367:l6227.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31791953?tool=bestpractice.com

[107]Boxhoorn L, van Dijk SM, van Grinsven J, et al. Immediate versus postponed intervention for infected necrotizing pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2021 Oct 7;385(15):1372-81.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34614330?tool=bestpractice.com

[108]Yang Y, Zhang Y, Wen S, et al. The optimal timing and intervention to reduce mortality for necrotizing pancreatitis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. World J Emerg Surg. 2023 Jan 27;18(1):9.

https://www.doi.org/10.1186/s13017-023-00479-7

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36707836?tool=bestpractice.com

[109]Nakai Y, Shiomi H, Hamada T, et al. Early versus delayed interventions for necrotizing pancreatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. DEN Open. 2023 Apr;3(1):e171.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/deo2.171

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36247314?tool=bestpractice.com

In patients who are clinically stable, the initial management of infected necrosis for patients should be a 30-day course of antibiotics to allow the inflammatory reaction to become better organized.[8]Tenner S, Vege S, Sheth S, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Mar 119(3):419-37.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/fulltext/2024/03000/american_college_of_gastroenterology_guidelines_.14.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38857482?tool=bestpractice.com

At this time, when the necrosis has become fully walled off, a decision can be made regarding the preferred method of drainage, which may include endoscopic, radiologic, and/or minimally invasive surgical intervention.[8]Tenner S, Vege S, Sheth S, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Mar 119(3):419-37.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/fulltext/2024/03000/american_college_of_gastroenterology_guidelines_.14.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38857482?tool=bestpractice.com

[47]Working Group IAP/APA Acute Pancreatitis Guidelines. IAP/APA evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2013 Jul-Aug;13(4 Suppl 2):e1-15.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1424390313005255?via%3Dihub

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24054878?tool=bestpractice.com

[110]Gurusamy KS, Belgaumkar AP, Haswell A, et al. Interventions for necrotising pancreatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Apr 16;(4):CD011383.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011383.pub2/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27083933?tool=bestpractice.com

[111]Gluck M, Ross A, Irani S, et al. Endoscopic and percutaneous drainage of symptomatic walled-off pancreatic necrosis reduces hospital stay and radiographic resources. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010 Dec;8(12):1083-8.

https://www.cghjournal.org/article/S1542-3565(10)00896-7/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20870036?tool=bestpractice.com

If there is no prompt response to antibiotics or if the clinical situation deteriorates, necrosectomy/debridement should be performed.[8]Tenner S, Vege S, Sheth S, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Mar 119(3):419-37.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/fulltext/2024/03000/american_college_of_gastroenterology_guidelines_.14.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38857482?tool=bestpractice.com

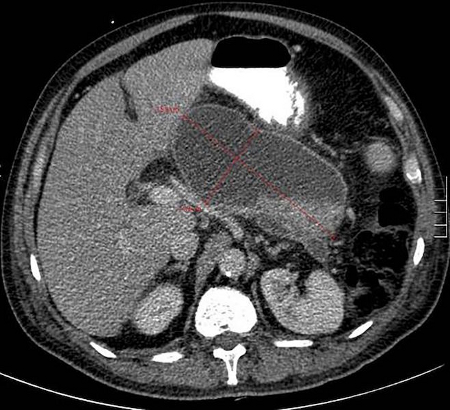

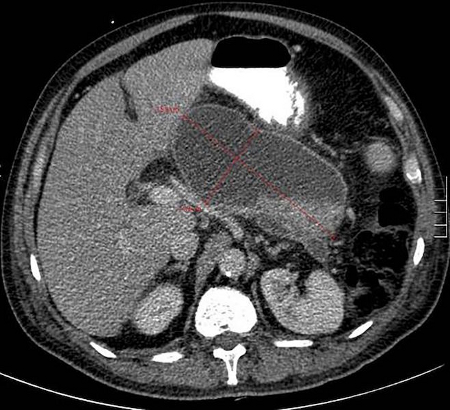

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Walled off pancreatic necrosisGut. 2017 Nov;66(11):2024-32; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Infected necrotic collection, not fully encapsulated, on day 20 after disease onsetGut. 2017 Nov;66(11):2024-32; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Infected necrotic collection, not fully encapsulated, on day 20 after disease onsetGut. 2017 Nov;66(11):2024-32; used with permission [Citation ends].

Pseudocysts

Pseudocysts are common and do not appear until at least 2-4 weeks after the onset of an episode of acute pancreatitis.[18]Hines OJ, Pandol SJ. Management of severe acute pancreatitis. BMJ. 2019 Dec 2;367:l6227.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31791953?tool=bestpractice.com

Early in the course of acute pancreatitis, large volumes of fluid may leave the intravascular compartment and form fluid collections in the abdomen. Most of this fluid is reabsorbed in the first few weeks.[18]Hines OJ, Pandol SJ. Management of severe acute pancreatitis. BMJ. 2019 Dec 2;367:l6227.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31791953?tool=bestpractice.com

However, in almost one third of patients, the fluid collections will persist and develop a fibrous nonepithelialized wall, becoming a pseudocyst. "Pseudocysts" diagnosed at initial presentation are likely to represent alternative pathology: either a patient with chronic pancreatitis, an old walled-off area of pancreatic necrosis, or a pancreatic cystic neoplasm.

Pancreatic necrosis, especially walled-off pancreatic necrosis (WOPN), cannot be differentiated from a pseudocyst by computed tomography. This is important as the treatment of a symptomatic or infected pseudocyst (abscess) and pancreatic necrosis are quite different. The differentiation between pancreatic necrosis and pseudocysts can only be made by the location of the cyst in relation to the pancreas. Whereas pseudocysts are located outside the parenchyma of the pancreas or adjacent structures, pancreatic necrosis will always involve the pancreas. Magnetic resonance imaging and endoscopic ultrasound (with fine needle aspiration) can determine the presence of tissue in WOPN but these imaging modalities are not used routinely.

Historically, patients with pseudocysts greater than 6 cm or enlarging on serial imaging underwent drainage. However, there is now a consensus that regardless of size, pseudocysts can be managed conservatively, with no intervention.[18]Hines OJ, Pandol SJ. Management of severe acute pancreatitis. BMJ. 2019 Dec 2;367:l6227.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31791953?tool=bestpractice.com

[112]Vitas GJ, Sarr MG. Selected management of pancreatic pseudocysts: operative versus expectant management. Surgery. 1992 Feb;111(2):123-30.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1736380?tool=bestpractice.com

If a pseudocyst becomes infected it is best described as an abscess, which requires antibiotics and drainage. Pseudocysts can become painful, or cause early satiety and weight loss when their size affects the stomach and bowel; drainage of these pseudocysts is recommended for symptom relief, regardless of infection.[8]Tenner S, Vege S, Sheth S, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Mar 119(3):419-37.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/fulltext/2024/03000/american_college_of_gastroenterology_guidelines_.14.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38857482?tool=bestpractice.com

[18]Hines OJ, Pandol SJ. Management of severe acute pancreatitis. BMJ. 2019 Dec 2;367:l6227.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31791953?tool=bestpractice.com

Depending on expertise available, drainage can be performed via endoscopic, radiologic, or surgical techniques.

]

[Evidence C]

]

[Evidence C]  [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Infected necrotic collection, not fully encapsulated, on day 20 after disease onsetGut. 2017 Nov;66(11):2024-32; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Infected necrotic collection, not fully encapsulated, on day 20 after disease onsetGut. 2017 Nov;66(11):2024-32; used with permission [Citation ends].