Approach

History

The initial step in diagnosing asbestosis or asbestos-related pleural disease is to obtain a history of exposure to asbestos that typically has occurred 20 or more years ago. A lifetime occupational history should be obtained that includes all jobs. History of asbestos exposure will usually be identified because of the type of work (shipyard, construction, maintenance, vehicle brake mechanic, asbestos cement, insulation or production of tiles, shingles, gaskets, brakes, or textiles) that the patient has done; exposure may also be identified in children or spouses of a worker who has brought asbestos home on clothes and boots.[1] There are certain geographic areas where natural occurrence of asbestos or industrial pollution puts residents at risk.[13][14]

The patient may complain of dyspnea on exertion and a dry, nonproductive cough. Both of these symptoms increase with disease progression but can be absent in a patient with early asbestosis and are usually absent in patients with pleural changes alone. Chest pain is not typically seen in patients with asbestosis or pleural changes. Symptoms of chest tightness from shortness of breath may be confused with chest pain. Severe unremitting chest pain raises concern about cancer, particularly mesothelioma.

Physical examination

Patients may develop crackles on lung auscultation and clubbing of fingers and toes, cyanosis, or decreased chest expansion as the severity of asbestosis increases. Crackles will first be appreciated at the lung bases. Physical findings will be normal in pleural disease unless the pleural thickening is diffuse or there is a benign pleural effusion. In these cases, breath sounds will be diminished on auscultation and dullness to percussion may be present.[1]

Investigations

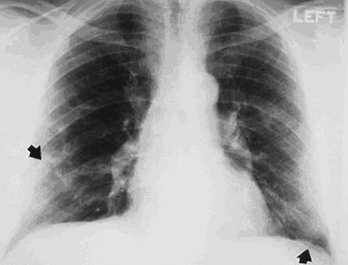

A chest x-ray is the initial screening test for patients with a history suggestive of asbestos exposure or symptoms of shortness of breath. Radiographic changes showing linear interstitial changes that are first seen in the lower lobes is the characteristic radiograph of asbestosis. Pleural thickening at the mid-thoracic level may be present alone or in conjunction with linear changes in the parenchyma. The majority of pleural changes are not calcified.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Posterior-anterior view of the chest with bibasilar linear interstitial changes consistent with asbestosisFrom the personal collection of Kenneth D. Rosenman MD [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Posterior-anterior view of the chest with "en face" pleural changes in the mid zones on the right and left (arrows)From the personal collection of Kenneth D. Rosenman MD [Citation ends].

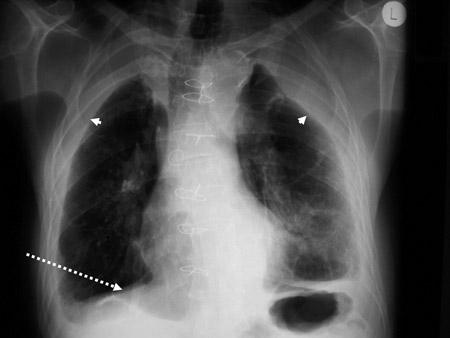

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Posterior-anterior view of the chest with "en face" pleural changes in the mid zones on the right and left (arrows)From the personal collection of Kenneth D. Rosenman MD [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Diffuse pleural thickening (arrowheads) and elevated left hemidiaphragm (dotted arrow)BMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.06.2008.0253 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Diffuse pleural thickening (arrowheads) and elevated left hemidiaphragm (dotted arrow)BMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.06.2008.0253 [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Posterior-anterior view of the chest with "mesa"-like pleural thickening of the left diaphragm and "in-profile" pleural thickening of the mid zones of both the left and right lungsFrom the personal collection of Kenneth D. Rosenman MD [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Posterior-anterior view of the chest with "mesa"-like pleural thickening of the left diaphragm and "in-profile" pleural thickening of the mid zones of both the left and right lungsFrom the personal collection of Kenneth D. Rosenman MD [Citation ends]. If the pleural changes are on the anterior or posterior chest wall, they may appear as interstitial changes on a posterior-anterior view but will not be seen in the parenchyma on a lateral view or computed tomography (CT) scan. Clinical judgment is key when interpreting technical quality, parenchymal abnormalities, and pleural abnormalities. No radiographic features are pathognomonic, and some unrelated features can mimic those caused by exposure. Diagnosis should only be made in the context of the clinical history and other examination results. For more detail on the International Labour Office (ILO) classification of radiographs of pneumoconioses, see Diagnostic criteria.

If the pleural changes are on the anterior or posterior chest wall, they may appear as interstitial changes on a posterior-anterior view but will not be seen in the parenchyma on a lateral view or computed tomography (CT) scan. Clinical judgment is key when interpreting technical quality, parenchymal abnormalities, and pleural abnormalities. No radiographic features are pathognomonic, and some unrelated features can mimic those caused by exposure. Diagnosis should only be made in the context of the clinical history and other examination results. For more detail on the International Labour Office (ILO) classification of radiographs of pneumoconioses, see Diagnostic criteria.

All patients with radiographic changes from asbestos, significant asbestos exposure, or symptoms of shortness of breath should have pulmonary function testing. Perform pulmonary function tests following standard guidelines.[16][17] Depending on the severity of asbestosis, pulmonary function may be normal or abnormal. The forced expiratory volume at 1 second (FEV₁) and forced vital capacity (FVC) can be used to demonstrate airflow limitation. Restrictive disease changes include reduced FVC with a normal FEV1/FVC ratio on spirometry, reduced slow vital capacity (SVC) and total lung capacity (TLC) on plethysmography, and reduced carbon monoxide diffusing capacity. Patients with asbestos exposure may also have obstructive changes with a reduced FEV1 and air trapping with increased residual volume.[18][19][20] The risk of obstructive changes is increased in patients who have a history of asbestos exposure and cigarette smoking.[1][18]

High-resolution CT (HRCT) scan of the chest is more sensitive than chest x-ray in identifying both parenchymal and pleural scarring.[1][4][8] An HRCT scan should be performed if the individual has shortness of breath not explained by the chest x-ray or pulmonary function test results. It may also be used to further characterize the extent of parenchymal disease or confirm that the pleural changes are not subpleural fat. Because of issues of cost, an HRCT scan is not typically performed in asymptomatic individuals if the chest x-ray and pulmonary function tests are normal.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan of the chest showing multiple examples of pleural thickening most with calcification (arrows)From the personal collection of Kenneth D. Rosenman MD [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan confirming symmetrical thickening (arrowheads) with a calcified pleural plaque (broken arrow, top right) and an area of rounded atelectasis (Blesovsky sign; dotted arrow, bottom right)Adapted from BMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.06.2008.0253 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan confirming symmetrical thickening (arrowheads) with a calcified pleural plaque (broken arrow, top right) and an area of rounded atelectasis (Blesovsky sign; dotted arrow, bottom right)Adapted from BMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.06.2008.0253 [Citation ends].

Bronchoscopic biopsy generally provides insufficient tissue to rule out asbestosis and is limited to evaluation for cancer, or if other clinical conditions are suspected. Given the rarity of identifying asbestos bodies in lavage fluid, bronchoscopic lavage has little clinical usage in evaluating a patient with suspected asbestosis, except in a research setting.

Open lung biopsy is rarely needed for the diagnosis. Its use should be limited to when cancer is suspected or in the absence of a known history of exposure to asbestos.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer