Approach

The approach to patients with symptoms of proctitis is guided by a careful history to differentiate between infectious and noninfectious causes.

A clear history that implicates sexually transmitted proctitis may be sufficient to warrant rectal swabs and empiric therapy.[13] Other causes of proctitis usually require endoscopic assessment to assist in the diagnosis.

Historical considerations

A careful history should elicit the common symptoms of proctitis, including diarrhea, urgency, rectal bleeding or discharge, lower abdominal cramps, tenesmus, and painful defecation. Systemic symptoms such as fever, malaise, weight loss, and vomiting also should be sought and may point to a more diffuse pathologic process. Diarrhea is not a prerequisite, as some patients with proctitis have constipation. In contrast to other causes, the onset of ischemic proctitis is usually abrupt. The history should include specific questions about:

Anal-receptive sexual intercourse

Immunosuppressive disease (e.g., HIV)

Celiac disease

Prior or recent history of pelvic irradiation

Recent hypotensive episode

Recent pelvic surgery

History of psychiatric disease involving self-harm

Use of immunosuppressive drugs such as prednisone, azathioprine/6-mercaptopurine, cyclosporine

Use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in suppository or oral form

Use of antibiotics in the last 6 months

Insertion of caustic agents per rectum (e.g., hydrogen peroxide)

Family history of inflammatory bowel disease

Recent travel to/living in an mpox endemic country or country with mpox outbreak, or contact with suspected, probable, or confirmed case, within the previous 21 days before symptom onset.[14][15]

Physical examination

On physical exam, the following should be noted:

Fever, hypotension, or tachycardia (sepsis, ischemic risk)

Cachexia, nail clubbing (celiac disease, Crohn disease)

Injection marks of intravenous drug use (lifestyle risk for HIV)

Lymph nodes (systemic infection such as cytomegalovirus [CMV], tuberculosis, lymphogranuloma venereum caused by Chlamydia trachomatis, mpox)

Abdominal tenderness (bowel infarction, colitis, Crohn ileitis)

Anal condylomata (anal infections), anal fissures (Crohn disease), anal chancre (syphilis)

Rectal blood (ulcerative proctitis, ischemic proctitis, radiation proctitis)

Rash (STI-associated rash; or STI-like in mpox infection [generalized sequential skin rash may also be present in mpox infection]).

A digital rectal exam should be performed, but this may be restricted due to severe tenderness. In such instances an examination under anesthesia is recommended. The presence of fever, abdominal tenderness, and guarding in the setting of suspected proctitis is a red flag and indicates more extensive colonic involvement by inflammation or infarction. Large-volume fresh rectal bleeding is also a red flag sign and raises the possibility of deep rectal ulcers in proctitis, which may require urgent hemostasis, and treatment of the underlying cause.

Tests

The appropriate tests needed for a patient with suspected proctitis can be tailored to the likely etiology based on the differential. Anoscopy or sigmoidoscopy is the definitive test to diagnose proctitis. Biopsies of the rectal mucosa are helpful in distinguishing acute from chronic proctitis. In the outpatient or emergency department setting some of the testing can be done immediately, including anoscopy, but other endoscopic evaluation may take day(s) to arrange.

If there is a history of anal-receptive sex, HIV, immunosuppression, or suspected mpox infection, further testing should include:

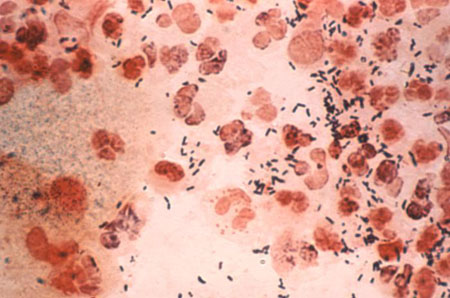

Rectal swab for microscopy, Gram stain, nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT), and culture (Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, Herpes simplex, Treponema pallidum). Consider genotyping for lymphogranuloma venereum in rectal specimens that test positive with NAAT for Chlamydia trachomatis.[13][16][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Gram stained photomicrograph of rectal smear revealing the presence of Gram-negative Neisseria gonorrhoeaeCDC/ Joe Miller [Citation ends].

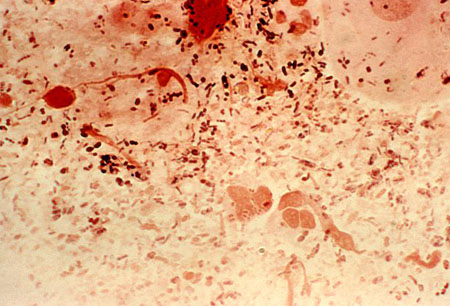

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Gram stained micrograph of rectal smear revealing the presence of Gram-negative Neisseria gonorrhoeae diplococci CDC/ Joe Miller [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Gram stained micrograph of rectal smear revealing the presence of Gram-negative Neisseria gonorrhoeae diplococci CDC/ Joe Miller [Citation ends].

Stool microscopy and culture (Shigella, Campylobacter, Salmonella, Clostridioides difficile, Giardia lamblia, Entamoeba histolytica).

Serologic testing (rapid plasma reagin test, Venereal Disease Research Laboratory test, fluorescent treponemal antibody- absorption test for Treponema pallidum).

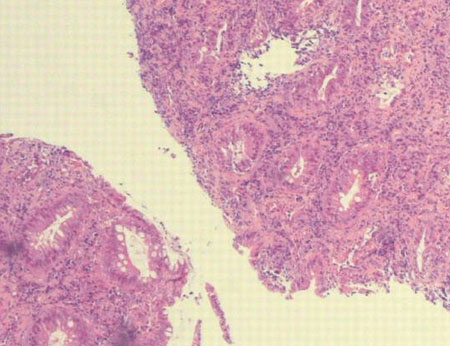

Tissue biopsy (immunofluorescence staining for T pallidum and Chlamydia trachomatis; polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for Herpes simplex and CMV).[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Rectal mucosa showing nonspecific active chronic proctitis in a patient with lymphogranuloma venereum (due to Chlamydia trachomatis)Laverse E, Jaleel H, Evans D, et al. Sexual history: its importance in averting detrimental misdiagnosis and delayed diagnosis. BMJ Case Reports. 2009; doi: 10.1136/bcr.04.2009.1773 [Citation ends].

HIV testing if HIV status is unknown.

PCR for mpox infection (positive for mpox or orthopoxvirus virus DNA).[17]

Broader testing for sexually associated causes of proctitis, proctocolitis and enteritis if testing for the above etiologies is negative and symptoms persist.[16]

If no clear cause of proctitis is evident from the history or physical exam, the following should be considered:

Full colonoscopy and terminal ileum intubation in patients with ulcerative proctitis or Crohn proctitis to establish the extent of the disease[18][19][20]

Abdominal computed tomography (CT) with intravenous and oral contrast if ischemic proctitis or Crohn disease is suspected; may also be considered in the acute setting if the patient presents with significant abdominal pain, rebound tenderness, guarding, or fever

Check of serum anti-tissue transglutaminase IgA antibody (anti-tTG, IgA) levels if celiac disease is suspected (e.g., anemia, chronic diarrhea, steatorrhea, young age). In cases of IgA deficiency associated with celiac disease IgG-deamidated gliadin peptide serology should be requested.

A biopsy of the affected area is often taken to confirm a diagnosis. Other confirmatory tests include CT enterography, small bowel follow-through, and magnetic resonance imaging.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer