Approach

The diagnosis of CVI is based on a careful clinical history, a thorough physical examination, and targeted investigations.

Clinical history

Patients may present with symptoms of heavy legs, leg fatigue, aching, and/or discomfort that develop and worsen towards the end of the day and on prolonged standing, and improve on elevation. Burning and itching of the skin and leg cramps may be present and are often associated with venous stasis and eczema. Initially, periodic elevation may reduce the swelling, but more severe cases almost always require additional control through compression.[2][11][14][15][16]

Physical examination

The lower extremities should be examined with the patient standing:[2]

Early signs of CVI include telangiectasias (dilated intradermal venules <1 mm in diameter), reticular veins (dilated, non-palpable, subdermal veins ≤3 mm in diameter), and corona phlebectatica (also known as malleolar flare or ankle flare). It consists of a fan-shaped pattern of small intradermal veins on the ankle or foot and is thought to be a common early physical sign of advanced venous disease.

Palpation for bulges consistent with varicose veins (dilated, palpable, subcutaneous veins) is undertaken. The extent, size, and location of the tortuous dilated veins are noted. Primary varicose veins are not commonly associated with significant oedema or skin changes, but occasionally pure superficial venous system incompetence can be associated with oedema, skin changes, and even frank ulceration.

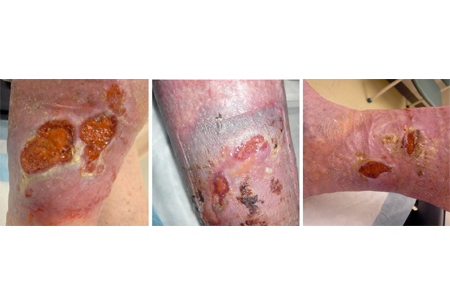

Ankle swelling (usually unilateral but may be bilateral) due to oedema is also common. It characteristically indents with pressure and initially occurs in the ankle region but may extend to the leg and foot.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Serial images of severe CVI (C6) and chronic ulceration of the right lower extremityFrom the collection of Dr Joseph L. Mills; used with permission [Citation ends].

Severe CVI is associated with characteristic skin changes such as atrophie blanche, lipodermatosclerosis, and hyperpigmentation. Atrophie blanche is characterised by localised, frequently round areas of white, shiny, atrophic skin surrounded by small dilated capillaries and sometimes areas of hyperpigmentation. Lipodermatosclerosis is a localised chronic inflammatory and fibrotic condition affecting the skin and subcutaneous tissues of the lower leg, especially in the supramalleolar region. When severe it may even lead to contracture of the Achilles tendon. Hyperpigmentation (usually a reddish-brown discoloration) of the ankle and lower leg is also known as brawny oedema. It results from extravasation of blood and deposition of haemosiderin in the tissues due to long-standing ambulatory venous hypertension.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Atrophie blanche in a patient with CVIFrom the collection of Dr Joseph L. Mills; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Lipodermatosclerosis and leg ulcer with hypercoagulable state and recurrent episodes of deep vein thrombosis (DVT)From the collection of Dr Joseph L. Mills; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Lipodermatosclerosis and leg ulcer with hypercoagulable state and recurrent episodes of deep vein thrombosis (DVT)From the collection of Dr Joseph L. Mills; used with permission [Citation ends].

Dry, scaling, eczematous skin changes are typical of venous stasis dermatitis.

Venous ulcers are located in the gaiter area (between the malleolus and mid-calf) of the calf, proximal and posterior to the medial malleolus, and occasionally superior to the lateral malleolus. Ulceration may be healed or active. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Serial images of recurrent venous ulcer with resolution at 3 monthsFrom the collection of Dr Joseph L. Mills; used with permission [Citation ends].

An important subset of patients with CVI have iliac vein obstruction, more commonly on the left than the right. Such patients usually present predominantly with swelling and lack other features of CVI.

Investigations

A variety of techniques may be employed to investigate patients with CVI:[2][10][16][17]

Duplex ultrasound imaging combines brightness-mode imaging and Doppler interrogation. It is the initial and most important primary diagnostic study. It can localise sites of obstruction and valvular reflux in both the deep and superficial venous systems. It should be noted that duplex ultrasound is operator dependent and that it should be performed as a reflux study and not only as an examination for acute deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Venous reflux is characterised by retrograde or reversed flow and a valve closure time of more than 0.5 seconds.

Ascending phlebography identifies the site and level of obstruction, as well as the presence and location of collaterals, but it has been supplanted by duplex imaging, except when used by a specialist to evaluate treatment options for complex CVI.

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance venography provide excellent anatomical detail, so are useful in evaluating congenital and complex or advanced cases of CVI.

Patients with unilateral leg oedema suggesting iliac vein obstruction should be evaluated with an ultrasound or a CT scan to rule out a pelvic or abdominal mass. If no evidence of extrinsic compression is found, the patient should be referred to a vascular specialist for further investigations, including an ascending phlebography. Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) is also used in specialised centres as a secondary test to evaluate the significance of iliac vein obstruction in complex cases of CVI. It is extremely useful in the diagnosis and therapy of iliac vein disease.

Air plethysmography is a non-invasive investigation that assesses venous function (identifying reflux and obstruction). It is primarily used for research and is not frequently used in the US outside of highly specialised centres or research settings.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer