Etiology

Syphilis is caused by Treponema pallidum subspecies pallidum, a motile spirochete bacterium. Humans are the only natural host. Until 2008, it had not been possible to cultivate T pallidum in vitro.[12]

Entry of the T pallidum organism into tissues probably occurs via areas of minor abrasion (at genital and mucous membrane sites) that result from trauma during sexual intercourse.[5][13]

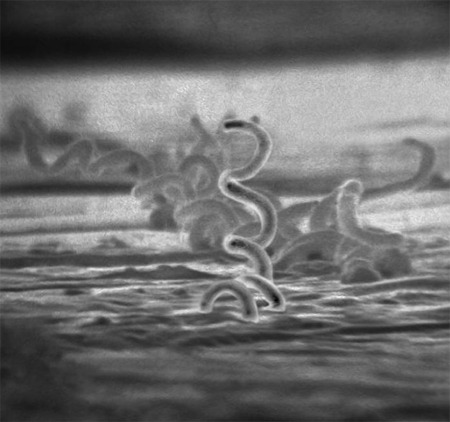

Orogenital sex is an important route of transmission and, therefore, transmission can occur despite the use of condoms.[1][14] The risk of acquiring syphilis after sex with someone with primary or secondary syphilis is between 30% and 60%.[15] Other modes of transmission are blood transfusion and transplacental transmission from mother to fetus. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Electron micrograph of Treponema pallidum on cultures of cotton-tail rabbit epithelium cellsCDC/Dr David Cox; used with permission [Citation ends].

Pathophysiology

Primary syphilis is characterized by ulceration (usually a solitary painless ulcer [chancre]) and local lymphadenopathy. The primary syphilis ulcer contains the Treponema pallidum bacterium and is characterized by mononuclear leukocytic infiltration. It heals spontaneously.

Secondary syphilis is caused by hematogenous spread of T pallidum. This leads to a widespread vasculitis. The mucocutaneous lesions of secondary syphilis also contain treponemes. The reasons for the resolution of secondary syphilis are unclear, but are likely to be related to a combination of macrophage-driven uptake of opsonized spirochetes and cell-mediated immunity.

Perivascular infiltrates composed principally of lymphocytes, histiocytes (macrophages), and plasma cells, accompanied by varying degrees of endothelial cell swelling and proliferation, are the histologic hallmarks of primary and secondary syphilis lesions. Likewise, T pallidumspirochetes are abundant in early syphilis lesions and are often observed in and around blood vessels and migrating from the dermis into the epidermis.

It is estimated that 14% to 40% of patients with untreated syphilis progress to tertiary syphilis (late symptomatic disease), which includes neurosyphilis, gummatous syphilis, and cardiovascular syphilis.[6] The theory that cell-mediated immunity is important in controlling syphilis infection is supported by the observation that progression to neurosyphilis may be more common in patients coinfected with HIV.[16]

Neurosyphilis may occur at any stage of infection with syphilis, and is characterized by a chronic, insidious inflammation of the meninges. It may occur in up to 10% of patients with untreated syphilis.[17][18] Neurosyphilis is caused by central nervous system invasion by the T pallidum bacterium. Early neurosyphilis syndromes are usually the result of meningovascular involvement; late neurosyphilis may occur due to meningovascular involvement or direct infection of the brain and spinal cord parenchyma. Parenchymal infection of the spinal cord by T pallidum results in tabes dorsalis. This condition is predominantly due to dorsal column loss. General paresis occurs with parenchymal involvement of the brain with neuronal loss.

Cardiovascular syphilis is characterized by aortic involvement as the T pallidum bacterium causes occlusion of the aortic vasa vasorum resulting in necrosis of the tunica media. Long-term inflammation and scarring weakens the aortic wall, leading to aortic aneurysm formation, as well as aortic incompetence and angina due to narrowing of the coronary ostia.

The hallmark of gummatous syphilis is the appearance of lesions on the skin, liver, bones, and testes. These lesions consist of granulomatous rubbery tissue with a necrotic center, and they may gradually replace normal tissue. T pallidum is rarely found within these lesions.

Classification

Classification according to transmission[1]

Acquired syphilis:

Transmission through direct person-to-person sexual contact with an individual who has early (primary or secondary) syphilis.

Congenital syphilis:

Transmission from mother to fetus during pregnancy

May result in miscarriage, stillbirth, or neonatal death[3]

Subdivided into:

Early (clinical manifestations occur from birth to 2 years of age)

Late (clinical manifestations occur >2 years of age).

Acquired syphilis, classified according to stage of infection[4]

Primary syphilis:

Initial inoculation of Treponema pallidum into tiny abrasions caused by sexual trauma results in local infection[5]

A single macule develops, which changes into a papule and then ulcerates, forming a chancre 9-90 days after exposure (usually 14-21 days after exposure).[5]

Secondary syphilis:

Clinical features develop 4 to 8 weeks after primary syphilis infection

Later presentation can occur up to 6 months after primary infection[6]

Characterized by spirochetemia and widespread dissemination of T pallidum to the skin and other tissues.

Early latent syphilis:

Asymptomatic infection diagnosed on the basis of positive serology alone, acquired <1 year previously (according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] criteria) or <2 years previously (according to World Health Organization [WHO] criteria).[7][8]

Relapse to secondary syphilis may occur during the early latent stage.

Late latent syphilis:

Asymptomatic infection acquired >1 year previously (according to CDC criteria) or >2 years previously (according to WHO criteria)[7][8]

The patient is not known to have been seronegative within the past year (according to CDC criteria) or past 2 years (according to WHO criteria).[7][8]

Tertiary syphilis:

It is estimated that 14% to 40% of patients with untreated syphilis progress to tertiary syphilis (late symptomatic disease)[6]

Characterized by chronic end-organ complications, often many years after initial infection

Includes cardiovascular syphilis, neurosyphilis, and gummatous syphilis.

Congenital syphilis, classified according to likelihood of infection[8]

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) describe four categories of congenital syphilis, based on: identification of maternal infection; adequacy of maternal treatment; presence of clinical, radiologic or laboratory evidence of syphilis in the neonate; and comparison of maternal (at delivery) and neonatal blood tests.

Confirmed proven or highly probable congenital syphilis

Any neonate (infant <30 days) with:

An abnormal physical exam that is consistent with congenital syphilis

A serum quantitative nontreponemal serologic titer that is fourfold (or greater) higher than the mother's titer at delivery (e.g., maternal titer = 1:2, neonatal titer ≥1:8 or maternal titer = 1:8, neonatal titer ≥1:32); or

A positive dark-field test or polymerase chain reaction of placenta, cord, lesions, or body fluids or a positive visualization of stained treponemal spirochetes in the placenta or cord using immunohistochemistry.

Possible congenital syphilis

Any neonate who has a normal physical exam and a serum quantitative nontreponemal serologic titer equal to or less than fourfold of the maternal titer at delivery (e.g., maternal titer = 1:8, neonatal titer ≤1:16) and one of the following:

The mother was not treated, was inadequately treated, or has no documentation of having received treatment

The mother was treated with erythromycin or a regimen other than those recommended by the CDC (i.e., a nonpenicillin G regimen)

The mother received the recommended regimen but treatment was initiated <30 days before delivery.

Congenital syphilis less likely

Any neonate who has a normal physical exam and a serum quantitative nontreponemal serologic titer equal or less than fourfold of the maternal titer at delivery (e.g., maternal titer = 1:8, neonatal titer ≤1:16) and both of the following are true:

The mother was treated during pregnancy, treatment was appropriate for the infection stage, and the treatment regimen was initiated ≥30 days before delivery

The mother has no evidence of reinfection or relapse.

Congenital syphilis unlikely

Any neonate who has a normal physical exam and a serum quantitative nontreponemal serologic titer equal to or less than fourfold of the maternal titer at delivery and both of the following are true:

The mother's treatment was adequate before pregnancy

The mother's nontreponemal serologic titer remained low and stable (i.e., serofast) before and during pregnancy and at delivery (e.g., Venereal Disease Research Laboratory test ≤1:2 or rapid plasma reagin test ≤1:4).

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer