Recommendations

Key Recommendations

General approach

SBO is an interruption of the patency of the gastrointestinal tract. The most common symptoms are abdominal pain, constipation or failure to pass flatus or stool per rectum, vomiting, and abdominal distention. If untreated, patients may develop progressive intestinal ischemia, necrosis, and perforation. Early diagnosis, monitoring, and intervention are therefore crucial.

Diagnosis should encompass the anticipated urgency for intervention. It is important to consider:

the cause of the obstruction,

whether the patient has a partial or complete SBO, and/or

whether the obstruction is simple (i.e., no peritonitis: may not require surgery) versus complicated (i.e., peritonitis is present: surgery definitely required).

The distinction between these various diagnostic possibilities can be based upon a combination of physical exam, abdominal CT scan, abdominal x-rays (in selected patients), and blood tests (e.g., white blood cell count).

In children, especially infants, diagnosis requires the exclusion of intestinal volvulus as a cause for the obstruction. Failure to establish the diagnosis in a timely manner can result in necrosis of the entire midgut and can be fatal if left untreated.

History

A detailed history provides insights into the onset and timing of the abdominal pain, the nature of the vomiting (which may be bilious), and the history of passage of stool/flatus. Past medical history may provide clues to a potential cause of the obstruction (e.g., a history of prior surgery may suggest adhesive disease).[15] Patients may also report a lump or swelling suggesting a hernia.

In cases of simple or partial SBO, patients may have an acute onset of symptoms, but will generally continue to pass gas and stool, although in lower quantities. Uncommonly, where there is hyperperistalsis distal to the obstruction, diarrhea may occur. Fever may be present, but it is likely to be mild. Vomiting is typically, but not always, present and is likely to be bilious.

In complicated SBO, patients report emesis, absolute constipation (no passage of flatus or stool), severe lethargy, and fever with rigors and typically have worse pain.

Patients may or may not experience a prodrome before the onset of full symptoms, such as nausea with either partial or complete SBO.

Physical examination

Patients with simple SBO present with abdominal distention and mild, diffuse 4-quadrant abdominal tenderness.[15] They may appear sick, with mild dehydration. If an underlying malignancy is the cause of the SBO, a mass may be palpated in the abdomen. Patients are also classically described as having high-pitched (tinkling) increased-frequency bowel sounds early in presentation, but bowel sounds may become less frequent in those with late obstruction as a result of intestinal muscular fatigue.[16][17] However, the accuracy of abdominal auscultation for bowel obstruction has been questioned.[18]

Patients with complicated SBO appear very ill at presentation. They demonstrate tachycardia and tachypnea, reflective of intravascular volume depletion and pain. In advanced stages, these patients may have fever and hypotension. The abdomen is usually distended, due to the obstructed bowel and the presence of ascites that develops in the setting of complete intestinal obstruction. Localized or generalized guarding together with signs of severe systemic illness, such as a high fever and tachycardia, may indicate that peritonitis has developed.[1]

Clinicians should also examine for the presence of incarcerated/strangulated hernias in the groin, umbilicus or prior incisions; the presence of surgical scars indicative of prior surgery; and manifestations of Crohn disease (e.g., mucositis, rash).

Investigations

When assessing a patient with intestinal obstruction, it is important to determine whether the patient has partial or complete, and simple or complicated SBO. In addition to the history and physical exam, the following investigations should be considered:

1. Computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen

A CT scan of the abdomen is the initial imaging investigation in patients with suspected intestinal obstruction.[17][19] The sensitivity of the abdominal CT scan in detecting intestinal obstruction is 84% to 95%, depending on the degree of obstruction.[20] CT scan has a high (approximately 90%) accuracy in predicting intestinal strangulation and therefore the need for urgent surgery.[21]

CT is also useful in diagnosing other complications of SBO, including ischemia or necrosis.[16][20][21][22] It can also detect underlying malignancy as a cause of SBO.[9]

A multidetector CT scanner and multiplanar reconstruction can be used, if available. They aid in the diagnosis and localization of the SBO.[1][19][23]

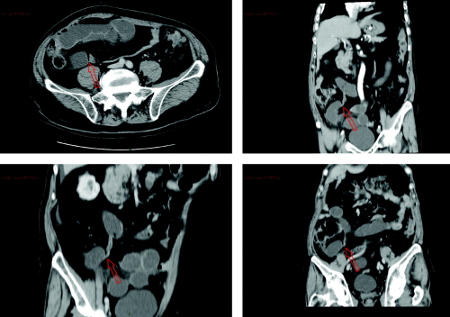

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Abdominal CT scan showing small bowel obstruction with multiple air-fluid levels, dilated bowel loops and a transition zone in the right iliac fossa. Red arrows indicate the evident transition zoneDi Saverio S, et al. Gut 2009; 58: 891-2; used with permission [Citation ends].

2. Abdominal x-rays

Although CT-scan has a higher sensitivity and specificity than abdominal x-rays, abdominal x-rays may be considered in the initial evaluation of patients with suspected intestinal obstruction, particularly in patients who are hemodynamically unstable or unable to undergo cross-sectional imaging, or who have equivocal clinical findings. They should be performed in the upright (or decubitus if the patient is unable to stand) and supine positions.[17][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Abdominal x-ray showing partial intestinal obstructionFrom the collection of Dr David J. Hackam [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Abdominal x-ray showing complete intestinal obstructionFrom the collection of Dr David J. Hackam [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Abdominal x-ray showing complete intestinal obstructionFrom the collection of Dr David J. Hackam [Citation ends].

Studies testing the sensitivity of abdominal x-rays for detecting SBO have shown widely divergent results.[19] In addition, abdominal x-rays will not give information about the etiology of obstruction, and findings may be normal in patients with early or proximal obstruction.[17] As such, they could prolong the evaluation period.[19] Hence, CT scanning has replaced abdominal radiographs as the standard of care for diagnosing SBO.[19]

3. Laboratory tests

Early in the course of investigation, a basic blood-work panel should be obtained, including complete blood count, to assess for the presence of leukocytosis and anemia. Tests of renal and pancreatic function should also be performed, to assess whether organ dysfunction is present. Electrolytes should also be measured.

Other useful imaging modalities include:

4. Water-soluble contrast study

In patients with acute SBO as a result of adhesions, water-soluble contrast challenge may help estimate whether conservative treatment has been successful. Patients in which the contrast reaches the colon by 24 hours rarely require surgery.[19][24][25]

5. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen

Not generally performed; the procedure adds no information to that from a well-performed CT scan. However, MRI can be useful in some cases, such as in Crohn disease subacute SBO where diagnosis has been difficult, or to avoid recurrent doses of ionizing radiation in young patients.[19]

6.Ultrasound of the abdomen

Rarely performed in adults with SBO unless CT scanning is not available or cannot be performed. However, ultrasound performed by a specialist technician can be a useful diagnostic modality in children.

7. Diagnostic laparotomy/laparoscopy

May be performed in those cases in which it is difficult to distinguish between simple and complicated SBO, or between SBO and some other cause of abdominal pain. This can take place either through an open incision (laparotomy) or via a minimally invasive approach in the hands of experienced individuals (diagnostic laparoscopy).

How to take a venous blood sample from the antecubital fossa using a vacuum needle.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer