When a diagnosis of acute cholecystitis is suspected, medical treatment, including nothing by mouth, intravenous fluids, antibiotics, and analgesia, together with close monitoring of blood pressure, pulse, and urinary output, should be initiated, with a view to carrying out early laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Simultaneously, the grade of severity needs to be established. Appropriate treatment should be performed in accordance with the severity grade. Operative risk should also be evaluated based on the severity grade.

Cholecystectomy

Cholecystectomy is the definitive treatment, as gallbladder inflammation often persists despite medical therapy.[52]Brazzelli M, Cruickshank M, Kilonzo M, et al. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of cholecystectomy compared with observation/conservative management for preventing recurrent symptoms and complications in adults presenting with uncomplicated symptomatic gallstones or cholecystitis: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2014 Aug;18(55):1-101.

https://www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/hta/hta18550#/full-report

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25164349?tool=bestpractice.com

This can be performed by laparoscopy or laparotomy (i.e., open approach); due to a low complication rate and shortened hospital stay laparoscopic approach is recommended first-line but should be avoided in cases of septic shock or where there are contraindications to anesthesia.[36]Pisano M, Allievi N, Gurusamy K, et al. 2020 World Society of Emergency Surgery updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute calculus cholecystitis. World J Emerg Surg. 2020 Nov 5;15(1):61.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7643471

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33153472?tool=bestpractice.com

Cholecystectomy is carried out as soon as possible after the onset of cholecystitis unless the patient is critically ill with severe cholecystitis and is thought to have a high operative risk, or inflammation is thought to have been present for more than 7 days. This is because of the high risk of intraoperative difficulties, which include heavy hemorrhage and possibly liver failure.

There is some evidence that patient selection may be improved by restricting surgery to those with unambiguous findings of cholecystitis. In one noninferiority study of patients with symptomatic uncomplicated gallstones, a restrictive selection process (using a triage instrument based on the Rome criteria of biliary colic) was associated with fewer cholecystectomies than usual care (selection for cholecystectomy left to the discretion of the surgeon).[53]van Dijk AH, Wennmacker SZ, de Reuver PR, et al. Restrictive strategy versus usual care for cholecystectomy in patients with gallstones and abdominal pain (SECURE): a multicentre, randomised, parallel-arm, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2019 Jun 8;393(10188):2322-30.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31036336?tool=bestpractice.com

Of those patients who did not undergo surgery (303), 34% (102) subsequently received an alternative diagnosis. The primary outcome, pain at 12 months, was similar between patients randomized to restrictive selection or to usual care.

Early cholecystectomy in older patients

One systematic review of 592 patients ages ≥70 years found that early cholecystectomy is a feasible treatment in older patients, with perioperative morbidity of 24% and perioperative mortality of 3.5%.[54]Loozen CS, van Ramshorst B, van Santvoort HC, et al. Early cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis in the elderly population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Surg. 2017;34(5):371-9.

https://www.karger.com/Article/FullText/455241

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28095385?tool=bestpractice.com

Older patients should be carefully selected; perioperative complications and mortality may be attributable to comorbid conditions and/or reduced physiologic reserves rather than the surgical procedure.[54]Loozen CS, van Ramshorst B, van Santvoort HC, et al. Early cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis in the elderly population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Surg. 2017;34(5):371-9.

https://www.karger.com/Article/FullText/455241

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28095385?tool=bestpractice.com

[55]Pisano M, Ceresoli M, Cimbanassi S, et al. 2017 WSES and SICG guidelines on acute calcolous cholecystitis in elderly population. World J Emerg Surg. 2019 Mar 4;14:10.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6399945

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30867674?tool=bestpractice.com

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy

The preferred surgical approach: early laparoscopic cholecystectomy (ELC, performed within 72 hours of symptom onset according to the 2018 Tokyo guidelines or within 7 days of hospital admission or 10 days of symptom onset according to the 2020 World Society of Emergency Surgery [WSES] guidelines) is safe and associated with less overall morbidity, shorter total hospital stay, and shorter duration of antibiotic therapy compared with delayed cholecystectomy (performed ≥6 weeks after the onset of symptoms), with no increased conversion rate to open cholecystectomy.[34]Okamoto K, Suzuki K, Takada T, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: flowchart for the management of acute cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018 Jan;25(1):55-72.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jhbp.516

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29045062?tool=bestpractice.com

[36]Pisano M, Allievi N, Gurusamy K, et al. 2020 World Society of Emergency Surgery updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute calculus cholecystitis. World J Emerg Surg. 2020 Nov 5;15(1):61.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7643471

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33153472?tool=bestpractice.com

[56]Overby DW, Apelgren KN, Richardson W, et al. SAGES guidelines for the clinical application of laparoscopic biliary tract surgery. Surg Endosc. 2010 Oct;24(10):2368-86.

http://www.sages.org/publications/guidelines/guidelines-for-the-clinical-application-of-laparoscopic-biliary-tract-surgery

[57]Wu XD, Tian X, Liu MM, et al. Meta-analysis comparing early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Br J Surg. 2015 Oct;102(11):1302-13.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26265548?tool=bestpractice.com

[58]Roulin D, Saadi A, Di Mare L, et al. Early versus delayed cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis, are the 72 hours still the rule? A randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2016 Nov;264(5):717-22.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27741006?tool=bestpractice.com

[59]Lyu Y, Cheng Y, Wang B, et al. Early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: an up-to-date meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Surg Endosc. 2018 Dec;32(12):4728-41.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30167953?tool=bestpractice.com

[  ]

What are the benefits and harms of performing early compared with delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy in people with acute cholecystitis?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.539/fullShow me the answer ELC is also associated with lower hospital costs, fewer work days lost, and greater patient satisfaction.[57]Wu XD, Tian X, Liu MM, et al. Meta-analysis comparing early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Br J Surg. 2015 Oct;102(11):1302-13.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26265548?tool=bestpractice.com

[60]Lo CM, Liu CL, Fan ST, et al. Prospective randomized study of early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Ann Surg. 1998 Apr;227(4):461-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1191296/pdf/annsurg00014-0013.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9563529?tool=bestpractice.com

[61]Lai PS, Kwong KH, Leung KL, et al. Randomized trial of early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Br J Surg. 1998 Jun;85(6):764-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9667702?tool=bestpractice.com

[62]Song GM, Bian W, Zeng XT, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: early or delayed? Evidence from a systematic review of discordant meta-analyses. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016 Jun;95(23):e3835.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4907666

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27281088?tool=bestpractice.com

[63]Cao AM, Eslick GD, Cox MR. Early laparoscopic cholecystectomy is superior to delayed acute cholecystitis: a meta-analysis of case-control studies. Surg Endosc. 2016 Mar;30(3):1172-82.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26139487?tool=bestpractice.com

[64]Khalid S, Iqbal Z, Bhatti AA. Early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2017 Oct-Dec;29(4):570-3.

http://jamc.ayubmed.edu.pk/index.php/jamc/article/view/3285/1618

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29330979?tool=bestpractice.com

]

What are the benefits and harms of performing early compared with delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy in people with acute cholecystitis?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.539/fullShow me the answer ELC is also associated with lower hospital costs, fewer work days lost, and greater patient satisfaction.[57]Wu XD, Tian X, Liu MM, et al. Meta-analysis comparing early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Br J Surg. 2015 Oct;102(11):1302-13.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26265548?tool=bestpractice.com

[60]Lo CM, Liu CL, Fan ST, et al. Prospective randomized study of early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Ann Surg. 1998 Apr;227(4):461-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1191296/pdf/annsurg00014-0013.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9563529?tool=bestpractice.com

[61]Lai PS, Kwong KH, Leung KL, et al. Randomized trial of early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Br J Surg. 1998 Jun;85(6):764-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9667702?tool=bestpractice.com

[62]Song GM, Bian W, Zeng XT, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: early or delayed? Evidence from a systematic review of discordant meta-analyses. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016 Jun;95(23):e3835.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4907666

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27281088?tool=bestpractice.com

[63]Cao AM, Eslick GD, Cox MR. Early laparoscopic cholecystectomy is superior to delayed acute cholecystitis: a meta-analysis of case-control studies. Surg Endosc. 2016 Mar;30(3):1172-82.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26139487?tool=bestpractice.com

[64]Khalid S, Iqbal Z, Bhatti AA. Early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2017 Oct-Dec;29(4):570-3.

http://jamc.ayubmed.edu.pk/index.php/jamc/article/view/3285/1618

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29330979?tool=bestpractice.com

Conversion to the open procedure may be required if there is significant inflammation, difficulty delineating the anatomy, or significant bleeding.[65]Jones MW, Deppen JG. Open cholecystectomy. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Apr 24.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448176

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28846294?tool=bestpractice.com

[66]Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. SSAT patient care guidelines. Treatment of gallstone and gallbladder disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007 Sep;11(9):1222-4. Conversion rates were assessed in one retrospective review of 493 patients with acute cholecystitis from 2010-2013. Severity classification according to the 2013 Tokyo guidelines was found to be the most powerful predictive factor for conversion.[67]Bouassida M, Chtourou MF, Charrada H, et al. The severity grading of acute cholecystitis following the Tokyo Guidelines is the most powerful predictive factor for conversion from laparoscopic cholecystectomy to open cholecystectomy. J Visc Surg. 2017 Sep;154(4):239-43.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28709978?tool=bestpractice.com

Male sex, diabetes mellitus, and total bilirubin level were also found to be independent risk factors for conversion to open surgery.[67]Bouassida M, Chtourou MF, Charrada H, et al. The severity grading of acute cholecystitis following the Tokyo Guidelines is the most powerful predictive factor for conversion from laparoscopic cholecystectomy to open cholecystectomy. J Visc Surg. 2017 Sep;154(4):239-43.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28709978?tool=bestpractice.com

The operating surgeon should be experienced in carrying out laparoscopic cholecystectomies, have access to intraoperative cholangiography should it be needed, and have a low threshold for conversion to open surgery if required.

Patients with Child-Turcotte-Pugh grade A or B liver cirrhosis who undergo laparoscopic cholecystectomy have fewer overall postoperative complications than those who undergo the open procedure.[68]de Goede B, Klitsie PJ, Hagen SM, et al. Meta-analysis of laparoscopic versus open cholecystectomy for patients with liver cirrhosis and symptomatic cholecystolithiasis. Br J Surg. 2013 Jan;100(2):209-16.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23034741?tool=bestpractice.com

The placement of a prophylactic drain does not reduce complications associated with laparoscopic cholecystectomy in patients with acute cholecystitis.[69]Picchio M, De Cesare A, Di Filippo A, et al. Prophylactic drainage after laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Updates Surg. 2019 Jun;71(2):247-54.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30945148?tool=bestpractice.com

Open cholecystectomy

May be appropriate for patients with gallbladder mass, extensive upper abdominal surgery, suspicion of malignancy, septic shock, or late third trimester of pregnancy, although increasing evidence supports the safety of laparoscopic cholecystectomy at all stages of pregnancy.[65]Jones MW, Deppen JG. Open cholecystectomy. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Apr 24.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448176

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28846294?tool=bestpractice.com

[66]Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. SSAT patient care guidelines. Treatment of gallstone and gallbladder disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007 Sep;11(9):1222-4.[70]Kothari S, Afshar Y, Friedman LS, et al. AGA clinical practice update on pregnancy-related gastrointestinal and liver disease: expert review. Gastroenterology. 2024 Oct;167(5):1033-45.

https://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(24)05118-7/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/39140906?tool=bestpractice.com

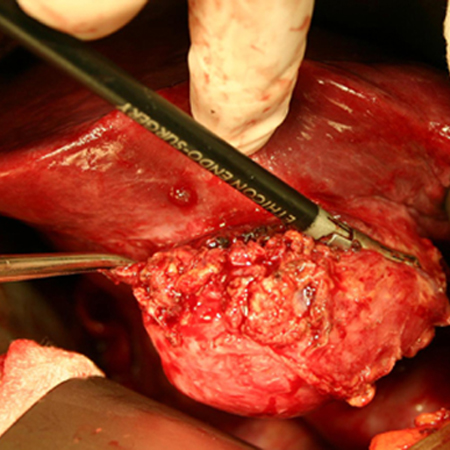

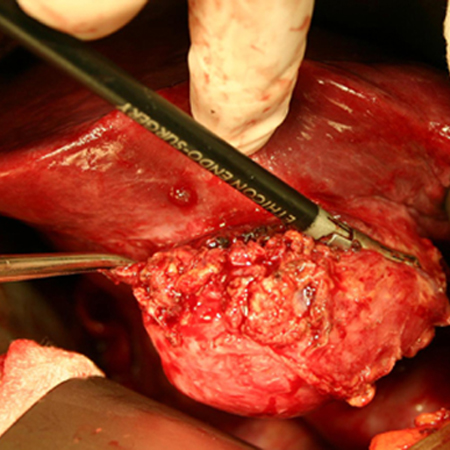

It is also indicated if there is significant gallbladder inflammation, difficulty delineating the anatomy, significant bleeding, presence of adhesions, or laparoscopic cholecystectomy complications. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Operative photo showing acute cholecystitisFrom the collection of Dr Charles Bellows; used with permission [Citation ends].

Percutaneous cholecystostomy

The 2020 WSES guidelines recommend early laparoscopic cholecystectomy whenever possible, even in subgroups of patients who are considered fragile.[36]Pisano M, Allievi N, Gurusamy K, et al. 2020 World Society of Emergency Surgery updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute calculus cholecystitis. World J Emerg Surg. 2020 Nov 5;15(1):61.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7643471

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33153472?tool=bestpractice.com

However, early gallbladder drainage (cholecystostomy) should be considered as an alternative option for the following patients:[36]Pisano M, Allievi N, Gurusamy K, et al. 2020 World Society of Emergency Surgery updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute calculus cholecystitis. World J Emerg Surg. 2020 Nov 5;15(1):61.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7643471

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33153472?tool=bestpractice.com

[71]Barak O, Elazary R, Appelbaum L, et al. Conservative treatment for acute cholecystitis: clinical and radiographic predictors of failure. Isr Med Assoc J. 2009 Dec;11(12):739-43.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20166341?tool=bestpractice.com

Ages >70 years, diabetes, a distended gallbladder, persistently elevated WBC (>15,000 cells/microliter). The presence of these factors may predict the development of complications (e.g., gangrenous cholecystitis) or failure of conservative treatment.

Retrospective data suggest that clinical improvement can be expected in 80% of patients with acute cholecystitis within 5 days of placement.[72]Byrne MF, Suhocki P, Mitchell RM, et al. Percutaneous cholecystostomy in patients with acute cholecystitis: experience of 45 patients at a US referral center. J Am Coll Surg. 2003 Aug;197(2):206-11.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12892798?tool=bestpractice.com

Contraindications include coagulopathy that cannot be corrected, massive ascites that cannot be drained, and suspicion for gangrenous or perforated cholecystitis.

Percutaneous cholecystostomy is a minimally invasive procedure most often performed in patients who have a high surgical risk, and occasionally in critically ill patients. During the procedure, the inflamed gallbladder is localized with sonography or fluoroscopy after the oral administration of contrast medium. Computed tomography-guided access may help if no sonographic window is found. A tube is then placed through the skin to drain or decompress the gallbladder.

Technical success of percutaneous cholecystostomy is high in experienced hands (95% to 100%), and complication rates are low. Complications include catheter dislodgment, vagal reaction, bile leakage and peritonitis, and hemorrhage.[73]Welschbillig-Meunier K, Pessaux P, Lebigot J, et al. Percutaneous cholecystostomy for high-risk patients with acute cholecystitis. Surg Endosc. 2005 Sep;19(9):1256-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16132331?tool=bestpractice.com

[74]Davis CA, Landercasper J, Gundersen LH, et al. Effective use of percutaneous cholecystostomy in high-risk surgical patients: techniques, tube management, and results. Arch Surg. 1999 Jul;134(7):727-31.

http://archsurg.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=390332

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10401823?tool=bestpractice.com

[75]Hatzidakis AA, Prassopoulos P, Petinarakis I, et al. Acute cholecystitis in high-risk patients: percutaneous cholecystostomy vs conservative treatment. Eur Radiol. 2002 Jul;12(7):1778-84.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12111069?tool=bestpractice.com

Outcomes

One systematic review failed to determine the role of percutaneous cholecystostomy in the clinical management of high-risk surgical patients with acute cholecystitis because of the limited number of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) and their small sample size.[76]Gurusamy KS, Rossi M, Davidson BR. Percutaneous cholecystostomy for high-risk surgical patients with acute calculous cholecystitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Aug 12;(8):CD007088.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD007088.pub2/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23939652?tool=bestpractice.com

One subsequent systematic review found that cholecystectomy is superior to percutaneous cholecystostomy with respect to mortality, length of hospital stay, and rate of readmission for biliary complaints in critically ill patients with acute cholecystitis.[77]Ambe PC, Kaptanis S, Papadakis M, et al. The treatment of critically ill patients with acute cholecystitis. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016 Aug 22;113(33-4):545-51.

https://www.aerzteblatt.de/int/archive/article/181145

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27598871?tool=bestpractice.com

However, all the studies included in this review were retrospective.[77]Ambe PC, Kaptanis S, Papadakis M, et al. The treatment of critically ill patients with acute cholecystitis. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016 Aug 22;113(33-4):545-51.

https://www.aerzteblatt.de/int/archive/article/181145

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27598871?tool=bestpractice.com

In the first RCT to compare laparoscopic cholecystectomy with percutaneous cholecystostomy in high-risk surgical patients (n=142, with acute calculous cholecystitis), cholecystectomy was associated with significantly fewer major complications (12% vs. 65%) and reduced rates of reintervention.[78]Loozen CS, van Santvoort HC, van Duijvendijk P, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus percutaneous catheter drainage for acute cholecystitis in high risk patients (CHOCOLATE): multicentre randomised clinical trial. BMJ. 2018 Oct 8;363:k3965.

https://www.bmj.com/content/363/bmj.k3965.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30297544?tool=bestpractice.com

Complications of percutaneous cholecystostomy

An incomplete or poor response within the first 48 hours may indicate complications (e.g., tube dislodgement, gallbladder wall necrosis) or the wrong diagnosis.[7]Indar AA, Beckingham IJ. Acute cholecystitis. BMJ. 2002 Sep 21;325(7365):639-43.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1124163

Extrahepatic and transhepatic approaches to percutaneous cholecystostomy have been advocated.[79]Bakkaloglu H, Yanar H, Guloglu R, et al. Ultrasound guided percutaneous cholecystostomy in high-risk patients for surgical intervention. World J Gastroenterol. 2006 Nov 28;12(44):7179-82.

http://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i44/7179.htm

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17131483?tool=bestpractice.com

A transhepatic route minimizes the risk of intraperitoneal bile leakage and inadvertent injury to the hepatic flexure of the colon.[73]Welschbillig-Meunier K, Pessaux P, Lebigot J, et al. Percutaneous cholecystostomy for high-risk patients with acute cholecystitis. Surg Endosc. 2005 Sep;19(9):1256-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16132331?tool=bestpractice.com

A subhepatic or transperitoneal approach is more favorable if stone extraction is planned due to the need for tract dilation.[74]Davis CA, Landercasper J, Gundersen LH, et al. Effective use of percutaneous cholecystostomy in high-risk surgical patients: techniques, tube management, and results. Arch Surg. 1999 Jul;134(7):727-31.

http://archsurg.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=390332

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10401823?tool=bestpractice.com

Patient follow-up

Patients treated with cholecystostomy tube can be discharged with their tube in place after the inflammatory process has resolved clinically. These patients should subsequently undergo a cholangiogram through the cholecystostomy tube (6-8 weeks) to see whether the cystic duct is open. If the duct is open and the patient is a good surgical candidate, they should be referred for cholecystectomy. However, more than 50% of patients with acute cholecystitis may undergo percutaneous cholecystostomy as definite treatment without subsequent cholecystectomy.[74]Davis CA, Landercasper J, Gundersen LH, et al. Effective use of percutaneous cholecystostomy in high-risk surgical patients: techniques, tube management, and results. Arch Surg. 1999 Jul;134(7):727-31.

http://archsurg.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=390332

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10401823?tool=bestpractice.com

Management based on severity grade (Tokyo guidelines)

The 2018 Tokyo guideline outlines treatment strategies for patients based on their severity grade: mild, moderate, or severe.[34]Okamoto K, Suzuki K, Takada T, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: flowchart for the management of acute cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018 Jan;25(1):55-72.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jhbp.516

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29045062?tool=bestpractice.com

The WSES takes a different approach, stratifying patients who are surgical candidates with common bile duct stones into low, moderate, or high risk and recommending intervention within 72 hours or at least within 7 days of hospital admission and within 10 days of onset of symptoms where appropriate.

This section outlines the Tokyo approach in more detail but it would be recommended to check local pathways and guidance.

Mild (grade I)

Defined as acute cholecystitis in a healthy patient with no organ dysfunction and mild inflammatory changes in the gallbladder; responds to initial medical treatment.[35]Yokoe M, Hata J, Takada T, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: diagnostic criteria and severity grading of acute cholecystitis (with videos). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018 Jan;25(1):41-54.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jhbp.515

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29032636?tool=bestpractice.com

Antibiotics are recommended if infection is suspected on the basis of laboratory and clinical findings.[80]Gomi H, Solomkin JS, Schlossberg D, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: antimicrobial therapy for acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018 Jan;25(1):3-16.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jhbp.518

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29090866?tool=bestpractice.com

Empiric intravenous antibiotic therapy should be started before the infecting isolates are identified. Antibiotic choice largely depends on local susceptibility patterns.[80]Gomi H, Solomkin JS, Schlossberg D, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: antimicrobial therapy for acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018 Jan;25(1):3-16.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jhbp.518

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29090866?tool=bestpractice.com

Local susceptibility patterns vary geographically and over time. The likelihood of resistance of the organism will also vary by whether the infection was hospital- or community-acquired, although there may be resistant organisms in the community.[80]Gomi H, Solomkin JS, Schlossberg D, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: antimicrobial therapy for acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018 Jan;25(1):3-16.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jhbp.518

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29090866?tool=bestpractice.com

Options include a suitable cephalosporin (e.g., ceftriaxone), a carbapenem (e.g., ertapenem), or a fluoroquinolone (e.g., ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin). Fluoroquinolones are only recommended if the susceptibility of cultured isolates is known or for patients with beta‐lactam allergies.[80]Gomi H, Solomkin JS, Schlossberg D, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: antimicrobial therapy for acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018 Jan;25(1):3-16.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jhbp.518

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29090866?tool=bestpractice.com

Systemic fluoroquinolone antibiotics may cause serious, disabling, and potentially long-lasting or irreversible adverse events. This includes, but is not limited to: tendinopathy/tendon rupture; peripheral neuropathy; arthropathy/arthralgia; aortic aneurysm and dissection; heart valve regurgitation; dysglycemia; and central nervous system effects including seizures, depression, psychosis, and suicidal thoughts and behavior.[81]Rusu A, Munteanu AC, Arbănași EM, et al. Overview of side-effects of antibacterial fluoroquinolones: new drugs versus old drugs, a step forward in the safety profile? Pharmaceutics. 2023 Mar 1;15(3):804.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10056716

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36986665?tool=bestpractice.com

Prescribing restrictions apply to the use of fluoroquinolones, and these restrictions may vary between countries. In general, fluoroquinolones should be restricted for use in serious, life-threatening bacterial infections only. Some regulatory agencies may also recommend that they must only be used in situations where other antibiotics that are commonly recommended for the infection are inappropriate (e.g., resistance, contraindications, treatment failure, unavailability). Consult your local guidelines and drug information source for more information on suitability, contraindications, and precautions.

The 2018 Tokyo guideline also recommends ampicillin/sulbactam, a penicillin with a beta-lactamase inhibitor, as an alternative option (if the resistance rate is <20%); however this is not recommended in North American guidelines due to widespread resistance.[80]Gomi H, Solomkin JS, Schlossberg D, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: antimicrobial therapy for acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018 Jan;25(1):3-16.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jhbp.518

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29090866?tool=bestpractice.com

[82]Mazuski JE, Tessier JM, May AK, et al. The Surgical Infection Society revised guidelines on the management of intra-abdominal infection. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2017 Jan;18(1):1-76.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/sur.2016.261?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori%3Arid%3Acrossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub++0pubmed

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28085573?tool=bestpractice.com

Anaerobic antibiotic cover (e.g., metronidazole, clindamycin) is warranted if a biliary‐enteric anastomosis is present and the patient is started on an empiric regimen that does not adequately cover Bacteroides species.[80]Gomi H, Solomkin JS, Schlossberg D, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: antimicrobial therapy for acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018 Jan;25(1):3-16.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jhbp.518

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29090866?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients are observed and treated with antibiotics. However, supportive care alone may be sufficient preceding delayed elective cholecystectomy.[83]van Dijk AH, de Reuver PR, Tasma TN, et al. Systematic review of antibiotic treatment for acute calculous cholecystitis. Br J Surg. 2016 Jun;103(7):797-811.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27027851?tool=bestpractice.com

Antibiotic therapy can be discontinued within 24 hours of cholecystectomy in grade I disease.[84]Huston JM, Barie PS, Dellinger EP, et al. The Surgical Infection Society guidelines on the management of intra-abdominal infection: 2024 update. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2024 Aug;25(6):419-35.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/sur.2024.137

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38990709?tool=bestpractice.com

However, if perforation, emphysematous changes, or necrosis of the gallbladder are noted during cholecystectomy, antibiotic therapy duration of 4-7 days is recommended.[80]Gomi H, Solomkin JS, Schlossberg D, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: antimicrobial therapy for acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018 Jan;25(1):3-16.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jhbp.518

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29090866?tool=bestpractice.com

Intravenous antibiotics may be switched to a suitable oral antibiotic regimen once the patient can tolerate oral feeding.[80]Gomi H, Solomkin JS, Schlossberg D, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: antimicrobial therapy for acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018 Jan;25(1):3-16.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jhbp.518

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29090866?tool=bestpractice.com

[85]Solomkin JS, Dellinger EP, Bohnen JM, et al. The role of oral antimicrobials for the management of intra-abdominal infections. New Horiz. 1998 May;6(2 suppl):S46-52.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9654311?tool=bestpractice.com

Medical treatment may be sufficient for patients with mild (grade I) disease, and urgent surgery may not be required if timely access to laparoscopic expertise is limited.[52]Brazzelli M, Cruickshank M, Kilonzo M, et al. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of cholecystectomy compared with observation/conservative management for preventing recurrent symptoms and complications in adults presenting with uncomplicated symptomatic gallstones or cholecystitis: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2014 Aug;18(55):1-101.

https://www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/hta/hta18550#/full-report

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25164349?tool=bestpractice.com

However, for most patients ELC should be considered the primary approach (within 1 week of onset of symptoms).[56]Overby DW, Apelgren KN, Richardson W, et al. SAGES guidelines for the clinical application of laparoscopic biliary tract surgery. Surg Endosc. 2010 Oct;24(10):2368-86.

http://www.sages.org/publications/guidelines/guidelines-for-the-clinical-application-of-laparoscopic-biliary-tract-surgery

[86]Gurusamy K, Samraj K, Gluud C, et al. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on the safety and effectiveness of early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Br J Surg. 2010 Feb;97(2):141-50.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/bjs.6870/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20035546?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients require adequate analgesia (e.g., acetaminophen and/or an opioid). Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may benefit patients with biliary colic but must be used with caution particularly in patients with a likelihood of early surgery, due to increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding.[29]European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL). EASL clinical practice guidelines on the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of gallstones. J Hepatol. 2016 Jul;65(1):146-81.

https://www.journal-of-hepatology.eu/article/S0168-8278(16)30032-0/fulltext

[87]Fraquelli M, Casazza G, Conte D, et al. Non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs for biliary colic. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Sep 9;(9):CD006390.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD006390.pub2/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27610712?tool=bestpractice.com

In practice, NSAIDs are usually avoided in patients with established cholecystitis.

The Tokyo guidelines state that ELC is the preferred treatment.[34]Okamoto K, Suzuki K, Takada T, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: flowchart for the management of acute cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018 Jan;25(1):55-72.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jhbp.516

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29045062?tool=bestpractice.com

[88]Mayumi T, Okamoto K, Takada T, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: management bundles for acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018 Jan;25(1):96-100.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jhbp.519

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29090868?tool=bestpractice.com

[89]Wakabayashi G, Iwashita Y, Hibi T, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: surgical management of acute cholecystitis: safe steps in laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis (with videos). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018 Jan;25(1):73-86.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jhbp.517

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29095575?tool=bestpractice.com

ELC (within 72 hours of onset of symptoms) has a clear benefit compared with delayed cholecystectomy (>6 weeks after index admission) in terms of complication rate, cost, quality of life, and hospital stay.[57]Wu XD, Tian X, Liu MM, et al. Meta-analysis comparing early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Br J Surg. 2015 Oct;102(11):1302-13.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26265548?tool=bestpractice.com

[60]Lo CM, Liu CL, Fan ST, et al. Prospective randomized study of early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Ann Surg. 1998 Apr;227(4):461-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1191296/pdf/annsurg00014-0013.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9563529?tool=bestpractice.com

[61]Lai PS, Kwong KH, Leung KL, et al. Randomized trial of early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Br J Surg. 1998 Jun;85(6):764-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9667702?tool=bestpractice.com

[62]Song GM, Bian W, Zeng XT, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: early or delayed? Evidence from a systematic review of discordant meta-analyses. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016 Jun;95(23):e3835.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4907666

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27281088?tool=bestpractice.com

[63]Cao AM, Eslick GD, Cox MR. Early laparoscopic cholecystectomy is superior to delayed acute cholecystitis: a meta-analysis of case-control studies. Surg Endosc. 2016 Mar;30(3):1172-82.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26139487?tool=bestpractice.com

[64]Khalid S, Iqbal Z, Bhatti AA. Early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2017 Oct-Dec;29(4):570-3.

http://jamc.ayubmed.edu.pk/index.php/jamc/article/view/3285/1618

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29330979?tool=bestpractice.com

There is no advantage to delaying cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis on the basis of outcomes.[90]Gutt CN, Encke J, Köninger J, et al. Acute cholecystitis: early versus delayed cholecystectomy, a multicenter randomized trial (ACDC study, NCT00447304). Ann Surg. 2013 Sep;258(3):385-93.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24022431?tool=bestpractice.com

Early surgery, even when performed in patients >72 hours from symptom onset, is safe and associated with less overall morbidity, shorter total hospital stay and duration of antibiotic therapy, and reduced cost compared with delayed cholecystectomy (performed ≥6 weeks after the onset of symptoms).[58]Roulin D, Saadi A, Di Mare L, et al. Early versus delayed cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis, are the 72 hours still the rule? A randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2016 Nov;264(5):717-22.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27741006?tool=bestpractice.com

[59]Lyu Y, Cheng Y, Wang B, et al. Early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: an up-to-date meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Surg Endosc. 2018 Dec;32(12):4728-41.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30167953?tool=bestpractice.com

[  ]

What are the benefits and harms of performing early compared with delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy in people with acute cholecystitis?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.539/fullShow me the answer

]

What are the benefits and harms of performing early compared with delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy in people with acute cholecystitis?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.539/fullShow me the answer

Perioperative administration of antibiotic prophylaxis: one randomized study of patients with mild acute cholecystitis found no difference in postoperative infection rates between people receiving a single preoperative intravenous dose of antibiotic (cefazolin) and the group that received an additional 3 days of intravenous antibiotics (cefuroxime and metronidazole) postoperatively.[91]Loozen CS, Kortram K, Kornmann VN, et al. Randomized clinical trial of extended versus single-dose perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis for acute calculous cholecystitis. Br J Surg. 2017 Jan;104(2):e151-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28121041?tool=bestpractice.com

Postoperative antibiotic therapy is typically reserved for selected patients and may not be required for patients who received preoperative and intraoperative antibiotics.[92]Regimbeau JM, Fuks D, Pautrat K, et al; FRENCH Study Group. Effect of postoperative antibiotic administration on postoperative infection following cholecystectomy for acute calculous cholecystitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014 Jul;312(2):145-54.

http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=1886190

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25005651?tool=bestpractice.com

[93]Kim EY, Yoon YC, Choi HJ, et al. Is there a real role of postoperative antibiotic administration for mildmoderate acute cholecystitis? A prospective randomized controlled trial. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2017 Oct;24(10):550-8.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jhbp.495

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28834296?tool=bestpractice.com

[94]Hajibandeh S, Popova P, Rehman S. Extended postoperative antibiotics versus no postoperative antibiotics in patients undergoing emergency cholecystectomy for acute calculous cholecystitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Innov. 2019 Aug;26(4):485-96.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30873901?tool=bestpractice.com

Percutaneous cholecystostomy should be considered if medical management fails and patients are poor surgical candidates. These patients should subsequently undergo a cholangiogram through the cholecystostomy tube (6-8 weeks) to see whether the cystic duct is open. If the duct is open and the patient is a good surgical candidate, they should be referred for cholecystectomy. Alternatively, endoscopic transpapillary gallbladder drainage or endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided gallbladder drainage can be considered in some resource settings.[95]Irani SS, Sharzehi K, Siddiqui UD. AGA clinical practice update on role of EUS-guided gallbladder drainage in acute cholecystitis: commentary. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 May;21(5):1141-7.

https://www.cghjournal.org/article/S1542-3565(23)00145-3/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36967319?tool=bestpractice.com

[96]Mori Y, Itoi T, Baron TH, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: management strategies for gallbladder drainage in patients with acute cholecystitis (with videos). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018 Jan;25(1):87-95.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jhbp.504/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28888080?tool=bestpractice.com

[97]Ahmed O, Rogers AC, Bolger JC, et al. Meta-analysis of outcomes of endoscopic ultrasound-guided gallbladder drainage versus percutaneous cholecystostomy for the management of acute cholecystitis. Surg Endosc. 2018 Apr;32(4):1627-35.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29404731?tool=bestpractice.com

More recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses have shown EUS gallbladder drainage to be associated with better clinical outcomes than percutaneous cholecystostomy and endoscopic transpapillary gallbladder drainage in high-risk surgical patients.[95]Irani SS, Sharzehi K, Siddiqui UD. AGA clinical practice update on role of EUS-guided gallbladder drainage in acute cholecystitis: commentary. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 May;21(5):1141-7.

https://www.cghjournal.org/article/S1542-3565(23)00145-3/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36967319?tool=bestpractice.com

[98]Luk SW, Irani S, Krishnamoorthi R, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gallbladder drainage versus percutaneous cholecystostomy for high risk surgical patients with acute cholecystitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endoscopy. 2019 Aug;51(8):722-32.

https://www.thieme-connect.com/products/ejournals/pdf/10.1055/a-0929-6603.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31238375?tool=bestpractice.com

[99]Mohan BP, Khan SR, Trakroo S, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gallbladder drainage, transpapillary drainage, or percutaneous drainage in high risk acute cholecystitis patients: a systematic review and comparative meta-analysis. Endoscopy. 2020 Feb;52(2):96-106.

https://www.thieme-connect.com/products/ejournals/pdf/10.1055/a-1020-3932.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31645067?tool=bestpractice.com

The American Gastroenterological Association suggests the use of EUS gallbladder drainage in high-risk surgical patients with acute cholecystitis, removal of percutaneous cholecystostomy drains in patients who are not candidates for cholecystectomy by allowing internal drainage, and drainage of malignant biliary obstruction in select patients.[95]Irani SS, Sharzehi K, Siddiqui UD. AGA clinical practice update on role of EUS-guided gallbladder drainage in acute cholecystitis: commentary. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 May;21(5):1141-7.

https://www.cghjournal.org/article/S1542-3565(23)00145-3/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36967319?tool=bestpractice.com

The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy also recommends EUS-guided gallbladder drainage for selected patients who are not candidates for cholecystectomy.[100]ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Pawa S, Marya NB, et al. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guideline on the role of therapeutic EUS in the management of biliary tract disorders: summary and recommendations. Gastrointest Endosc. 2024 Dec;100(6):967-79.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/39078360?tool=bestpractice.com

There is good evidence to show that this procedure is effective in treating acute cholecystitis, though it is a technically challenging procedure that should only be done in specialist centers by clinicians trained and experienced in using this procedure for gallbladder drainage.[99]Mohan BP, Khan SR, Trakroo S, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gallbladder drainage, transpapillary drainage, or percutaneous drainage in high risk acute cholecystitis patients: a systematic review and comparative meta-analysis. Endoscopy. 2020 Feb;52(2):96-106.

https://www.thieme-connect.com/products/ejournals/pdf/10.1055/a-1020-3932.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31645067?tool=bestpractice.com

[101]Fabbri C, Binda C, Sbrancia M, et al. Determinants of outcomes of transmural EUS-guided gallbladder drainage: systematic review with proportion meta-analysis and meta-regression. Surg Endosc. 2022 Nov;36(11):7974-85.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35652964?tool=bestpractice.com

[102]Podboy A, Yuan J, Stave CD, et al. Comparison of EUS-guided endoscopic transpapillary and percutaneous gallbladder drainage for acute cholecystitis: a systematic review with network meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021 Apr;93(4):797-804.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32987004?tool=bestpractice.com

[103]Hemerly MC, de Moura DTH, do Monte Junior ES, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided cholecystostomy versus percutaneous cholecystostomy (PTC) in the management of acute cholecystitis in patients unfit for surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2023 Apr;37(4):2421-38.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36289089?tool=bestpractice.com

Moderate (grade II)

Defined as acute cholecystitis associated with any one of the following: elevated white blood cell count (>18,000/microliter), palpable tender mass in the right upper abdominal quadrant, duration of complaints >72 hours, and marked local inflammation (gangrenous cholecystitis, pericholecystic abscess, hepatic abscess, biliary peritonitis, emphysematous cholecystitis).[35]Yokoe M, Hata J, Takada T, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: diagnostic criteria and severity grading of acute cholecystitis (with videos). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018 Jan;25(1):41-54.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jhbp.515

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29032636?tool=bestpractice.com

Moderate-grade cholecystitis usually does not respond to the initial medical treatment.

When a diagnosis of acute cholecystitis is suspected, medical treatment, including nothing by mouth, intravenous fluids, antibiotics, and analgesia, together with close monitoring of blood pressure, pulse, and urinary output, should be initiated.

Antibiotics are required if infection is suspected on the basis of laboratory and clinical findings. Empiric intravenous antibiotic therapy should be started before the infecting isolates are identified. Antibiotic choice largely depends on local susceptibility patterns.[80]Gomi H, Solomkin JS, Schlossberg D, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: antimicrobial therapy for acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018 Jan;25(1):3-16.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jhbp.518

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29090866?tool=bestpractice.com

Local susceptibility patterns vary geographically and over time. The likelihood of resistance of the organism will also vary by whether the infection was hospital- or community-acquired, although there may be resistant organisms in the community.[80]Gomi H, Solomkin JS, Schlossberg D, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: antimicrobial therapy for acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018 Jan;25(1):3-16.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jhbp.518

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29090866?tool=bestpractice.com

Choice of antibiotic regimen follows the same principles as for grade I disease and is detailed in the section above. Antibiotic therapy can be discontinued within 24 hours after cholecystectomy is performed in grade II disease. However, if perforation, emphysematous changes, or necrosis of gallbladder are noted during cholecystectomy, antibiotic therapy duration of 4-7 days is recommended.[80]Gomi H, Solomkin JS, Schlossberg D, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: antimicrobial therapy for acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018 Jan;25(1):3-16.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jhbp.518

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29090866?tool=bestpractice.com

Intravenous antibiotics may be switched to a suitable oral antibiotic regimen once the patient can tolerate oral feeding.[80]Gomi H, Solomkin JS, Schlossberg D, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: antimicrobial therapy for acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018 Jan;25(1):3-16.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jhbp.518

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29090866?tool=bestpractice.com

[85]Solomkin JS, Dellinger EP, Bohnen JM, et al. The role of oral antimicrobials for the management of intra-abdominal infections. New Horiz. 1998 May;6(2 suppl):S46-52.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9654311?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients who do not improve under conservative treatment are referred for either surgery or percutaneous cholecystostomy, usually within 1 week of onset of symptoms.[56]Overby DW, Apelgren KN, Richardson W, et al. SAGES guidelines for the clinical application of laparoscopic biliary tract surgery. Surg Endosc. 2010 Oct;24(10):2368-86.

http://www.sages.org/publications/guidelines/guidelines-for-the-clinical-application-of-laparoscopic-biliary-tract-surgery

[86]Gurusamy K, Samraj K, Gluud C, et al. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on the safety and effectiveness of early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Br J Surg. 2010 Feb;97(2):141-50.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/bjs.6870/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20035546?tool=bestpractice.com

ELC could be indicated if advanced laparoscopic techniques and skills are available.[34]Okamoto K, Suzuki K, Takada T, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: flowchart for the management of acute cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018 Jan;25(1):55-72.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jhbp.516

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29045062?tool=bestpractice.com

In patients with moderately severe cholecystitis, where there is no organ dysfunction but there is extensive disease in the gallbladder (which can confer difficulty in safely carrying out a cholecystectomy), ELC or open cholecystectomy by a highly experienced surgeon is preferred. If operative conditions make anatomic identification difficult, ELC should be promptly terminated by conversion to open cholecystostomy. Interval cholecystectomy can then be performed in 6-8 weeks.[34]Okamoto K, Suzuki K, Takada T, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: flowchart for the management of acute cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018 Jan;25(1):55-72.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jhbp.516

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29045062?tool=bestpractice.com

Limiting factors to emergency surgery include availability of surgical staff, theater space, and radiologic investigations. Percutaneous cholecystostomy should be considered for poor surgical candidates. These patients should subsequently undergo a cholangiogram through the cholecystostomy tube (6-8 weeks) to see whether the cystic duct is open.[35]Yokoe M, Hata J, Takada T, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: diagnostic criteria and severity grading of acute cholecystitis (with videos). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018 Jan;25(1):41-54.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jhbp.515

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29032636?tool=bestpractice.com

[36]Pisano M, Allievi N, Gurusamy K, et al. 2020 World Society of Emergency Surgery updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute calculus cholecystitis. World J Emerg Surg. 2020 Nov 5;15(1):61.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7643471

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33153472?tool=bestpractice.com

If the duct is open and the patient is a good surgical candidate, they should be referred for cholecystectomy.

Severe (grade III)

Defined as organ dysfunction in at least any one of the following organs/systems: cardiovascular (hypotension requiring treatment with dopamine beyond a certain dose, or any dose of norepinephrine); central nervous system (decreased level of consciousness); respiratory (PaO2/FiO2 ratio <300); renal (oliguria, creatinine >2.0 mg/dL); hepatic (INR >1.5); hematologic (platelet count <100,000 cells/microliter); severe local inflammation.[35]Yokoe M, Hata J, Takada T, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: diagnostic criteria and severity grading of acute cholecystitis (with videos). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018 Jan;25(1):41-54.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jhbp.515

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29032636?tool=bestpractice.com

Intensive supportive care is required to monitor and treat organ dysfunction. Appropriate organ support may include oxygen, noninvasive/invasive positive pressure ventilation, or use of vasopressors alongside usual initial medical management (e.g., intravenous fluids, correction of electrolyte disturbances, and analgesics).[34]Okamoto K, Suzuki K, Takada T, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: flowchart for the management of acute cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018 Jan;25(1):55-72.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jhbp.516

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29045062?tool=bestpractice.com

Requires urgent management of severe local inflammation by percutaneous cholecystostomy followed, where indicated, by delayed elective cholecystectomy 2-3 months later, when the patient's general condition has improved.[34]Okamoto K, Suzuki K, Takada T, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: flowchart for the management of acute cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018 Jan;25(1):55-72.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jhbp.516

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29045062?tool=bestpractice.com

[89]Wakabayashi G, Iwashita Y, Hibi T, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: surgical management of acute cholecystitis: safe steps in laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis (with videos). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018 Jan;25(1):73-86.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jhbp.517

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29095575?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients treated with cholecystostomy can be discharged with their tube in place after the inflammatory process has resolved clinically. These patients should subsequently undergo a cholangiogram through the cholecystostomy tube (6-8 weeks) to see whether the cystic duct is open. If the duct is open and the patient is a good surgical candidate, they should be referred for cholecystectomy.

Antibiotics are required if infection is suspected on the basis of laboratory and clinical findings. Empiric intravenous antibiotic therapy should be started before the infecting isolates are identified. Antibiotic choice largely depends on local susceptibility patterns. Local susceptibility patterns vary geographically and over time. The likelihood of resistance of the organism will also vary by whether the infection was hospital- or community-acquired, although there may be resistant organisms in the community.[80]Gomi H, Solomkin JS, Schlossberg D, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: antimicrobial therapy for acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018 Jan;25(1):3-16.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jhbp.518

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29090866?tool=bestpractice.com

Options include a penicillin with a beta-lactamase inhibitor (e.g., piperacillin/tazobactam), a suitable cephalosporin (e.g., cefepime), a carbapenem (e.g., ertapenem, meropenem), or a monobactam (e.g., aztreonam).[80]Gomi H, Solomkin JS, Schlossberg D, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: antimicrobial therapy for acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018 Jan;25(1):3-16.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jhbp.518

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29090866?tool=bestpractice.com

Vancomycin is recommended as an adjunct to cover Enterococcus species in grade III infections. Linezolid or daptomycin are recommended in place of vancomycin if vancomycin‐resistant Enterococcus is known to be colonizing the patient, if previous treatment included vancomycin, and/or if the organism is common in the community.[80]Gomi H, Solomkin JS, Schlossberg D, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: antimicrobial therapy for acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018 Jan;25(1):3-16.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jhbp.518

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29090866?tool=bestpractice.com

Anaerobic antibiotic cover (e.g., metronidazole, clindamycin) is warranted if a biliary‐enteric anastomosis is present and the patient is started on an empiric regimen that does not adequately cover Bacteroides species.[80]Gomi H, Solomkin JS, Schlossberg D, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: antimicrobial therapy for acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018 Jan;25(1):3-16.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jhbp.518

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29090866?tool=bestpractice.com

Once the source of infection is controlled, the recommended duration of antibiotic treatment is 4-7 days. If bacteremia with gram‐positive cocci (e.g., Enterococcus species, Streptococcus species) is present, a duration of at least 2 weeks is recommended.[80]Gomi H, Solomkin JS, Schlossberg D, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: antimicrobial therapy for acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018 Jan;25(1):3-16.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jhbp.518

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29090866?tool=bestpractice.com

If residual stones or obstruction of the bile tract are present, treatment should be continued until these anatomic problems are resolved. If liver abscess is present, treatment should be continued until clinical, biochemic, and radiologic follow‐up demonstrates complete resolution of the abscess.[80]Gomi H, Solomkin JS, Schlossberg D, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: antimicrobial therapy for acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018 Jan;25(1):3-16.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jhbp.518

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29090866?tool=bestpractice.com

Intravenous antibiotics may be switched to a suitable oral antibiotic regimen once the patient can tolerate oral feeding.[80]Gomi H, Solomkin JS, Schlossberg D, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: antimicrobial therapy for acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018 Jan;25(1):3-16.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jhbp.518

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29090866?tool=bestpractice.com

[85]Solomkin JS, Dellinger EP, Bohnen JM, et al. The role of oral antimicrobials for the management of intra-abdominal infections. New Horiz. 1998 May;6(2 suppl):S46-52.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9654311?tool=bestpractice.com

]

ELC is also associated with lower hospital costs, fewer work days lost, and greater patient satisfaction.[57][60][61][62][63][64]

]

ELC is also associated with lower hospital costs, fewer work days lost, and greater patient satisfaction.[57][60][61][62][63][64]

]

]