Etiology

In the majority of patients with myocarditis, there is no identified cause and the case is classified as idiopathic or undefined cause. In those with an identified cause, common etiologies may be infectious or noninfectious.[4][5][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35]

Infectious causes:

Viral

SARS-CoV-2

Influenza A and B

Adenovirus

Coxsackie B

Flaviviruses (e.g., dengue, yellow fever)

Hepatitis B and C

Mumps

Measles

Rubella

Human immunodeficiency virus-1

Echoviruses

Epstein-Barr virus

Cytomegalovirus

Parvovirus B-19

Human herpes virus- 6

Polioviruses

Rabies

Varicella-zoster

Herpes simplex

Vaccinia

Chikungunya

Respiratory syncytial virus

Bacterial

Mycobacterial (tuberculosis)

Streptococcal species

Mycoplasma pneumoniae

Chlamydia species

Corynebacterium diphtheriae

Staphylococcal species

Clostridium species

Neisseriaspecies

Spirochetal

Borrelia burgdorferi (lyme disease)

Leptospira (leptospirosis)

Treponema pallidum (syphilis)

Mycotic

Aspergillus

Candida

Coccidioides

Cryptococcus

Histoplasma

Nocardia

Blastomyces

Protozoal and Helminthic

Trypanosoma cruzi (Chagas disease)

Trypanosoma brucei (African sleeping sickness)

Toxoplasma gondii (toxoplasmosis)

Plasmodium falciparum (malaria)

Taenia solium (cysticercosis)

Schistosoma (schistosomiasis)

Toxocara canis (visceral larva migrans)

Rickettsial

Coxiella burnetii (Q fever)

Rickettsia rickettsii (Rocky Mountain spotted fever)

Noninfectious causes:

Toxins/drug-related

Anthracyclines (e.g., doxorubicin, daunorubicin, epirubicin, idarubicin)

Fluoropyrimidines (e.g., fluorouracil, capecitabine)

Immunotherapies (e.g., ipilimumab, tremelimumab, nivolumab, pembrolizumab, cemiplimab, atezolizumab, avelumab, durvalumab, and trastuzumab)

Arsenic

Zidovudine

Carbon monoxide

Ethanol

Iron

Interleukin-2

Cocaine

Amphetamine

Smallpox and mpox vaccine

SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) mRNA vaccines (may occur with other types of COVID-19 vaccines)

Catecholamines (e.g., epinephrine, norepinephrine, dopamine)

Cyclophosphamide

Heavy metals (copper, iron, lead)

Radiation

Hypersensitivity

Antibiotics (penicillins, cephalosporins, sulfonamides)

Amphotericin B

Thiazide diuretics

Anticonvulsants (carbamazepine, phenytoin, phenobarbital)

Digoxin

Lithium

Amitriptyline

Clozapine

Snake venom

Bee venom

Black widow spider venom

Scorpion venom

Wasp venom

Systemic disorders

Rheumatic heart disease

Autoimmune diseases (systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis)

Inflammatory bowel disease (celiac disease, Crohn disease)

Giant cell myocarditis

Collagen vascular diseases

Sarcoidosis (idiopathic granulomatous myocarditis)

Thyrotoxicosis

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly known as Wegener granulomatosis)

Loeffler syndrome (hypereosinophilic syndrome with eosinophilic endomyocardial disease)

Graft-versus-host disease

Post-heart transplant rejection

For more information on the association between SARS-CoV-2 infection, SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, and myocarditis, please see Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Pathophysiology

The pathogenesis of myocarditis is not entirely clear. However, in viral-mediated myocarditis, animal models have implicated three significant mechanisms:[25][36]

An infectious organism directly invades the myocardium

Local and systemic immunologic activation quickly ensues

Cellular (CD4+) and humoral (B-cell clonal multiplication) activation occurs, causing worsening local inflammation, antiheart antibody production, and further myonecrosis.

All three may occur in the same host. However, the predominant pathway may differ depending on the individual characteristics of the infectious species, the innate defenses of the host organism, and potentially genetic predilections. The “two-hit” hypothesis suggests that patients with genetic mutations may be predisposed to developing myocarditis upon exposure to certain factors, such as infectious agents. This theory is supported by clinical studies in both children and adults.[37][38][39] However, more studies are needed.

The first phase of viral-mediated myocarditis is characterized by viremia in the host organism. During this time, the cardiotropic RNA virus enters the host myocyte via receptor-mediated endocytosis.[40][41] Here, the viral RNA is translated into viral protein, and the viral genome is incorporated into the host-cell DNA as double-stranded RNA. This latter mechanism has been shown to cleave dystrophin, which is thought to directly cause myocyte dysfunction.

During the second and third phases, macrophages, natural killer cells, and other inflammatory cells infiltrate the myocardium. Once in the myocardium, these cells express inflammatory cytokines including interleukin-1, interleukin-2, interferon-gamma, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF).[42] This results in increased cytokine production and causes endothelial cell activation resulting in further infiltration of inflammatory cells. TNF alone also acts as a negative inotrope.[43] In addition, autoantibodies directed against myocardial contractile and structural proteins are produced. This is thought to have cytopathic effects on energy metabolism, calcium homeostasis, and signal transduction, and also to cause complement activation resulting in the lysis of myocytes.[44]

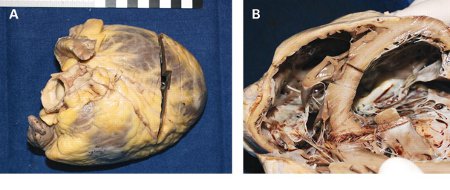

Other etiologies can trigger the inflammatory response via various pathways leading to myocardial inflammation, infiltration, and injury.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Autopsy findings in a patient with myocarditis. The explanted heart (A and B) is enlarged and thinned with dilatation mainly of the right ventricle. The right atrium is moderately dilated and the left atrium is not enlarged (B)From: Rasmussen TB, Dalager S, Andersen NH, et al. BMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.09.2008.0997 [Citation ends].

Classification

Clinicopathologic classification[2]

Fulminant myocarditis: presentation with acute illness following a distinct viral syndrome. Histologic study reveals multiple foci of active myocarditis. Clinical presentation consists of severe cardiovascular compromise and ventricular dysfunction. This subgroup has an extremely high risk for severe disease, rapid deterioration, and sudden death. However, if supported well, including with mechanical support, there is a good chance of recovery.

Acute myocarditis: presentation with insidious onset of illness and evidence of established ventricular dysfunction. This subgroup may progress to dilated cardiomyopathy.

Chronic active myocarditis: presentation with insidious onset of illness with clinical and histologic relapses with development of left ventricular dysfunction and associated chronic recurrent inflammatory changes.

Chronic persistent myocarditis: presentation with insidious onset of illness characterized by a persistent histologic infiltrate frequently with foci of myocyte necrosis. Clinically, no ventricular dysfunction is present despite other cardiovascular symptoms (such as palpitations or chest pain).

Important variants

Lymphocytic (viral) myocarditis

The most common cause of myocarditis in the US, it is characterized by myocardial infiltrate with lymphocytes as the predominant inflammatory cell.[3][4][5][6]

Chagas heart disease

Although exceedingly rare in the US, Trypanosoma cruzi infection-associated myocarditis is the most common cause of heart failure in the world.[7]

Histopathologically characterized by a predominantly lymphocytic cellular myocardial infiltrate in the setting of a known history of T cruzi infection. Using specialized sensitive immunohistochemical techniques and polymerase chain reaction amplification methods, parasitic antigens can be found by endomyocardial biopsy.[8]

Giant cell myocarditis

A rare and frequently fatal inflammatory disorder of cardiac muscle histologically characterized by:

Inflammatory infiltrate with the presence of multinucleated giant cells

Widespread degeneration and necrosis of myocardial fibers

Absence of granulomas (to distinguish from cardiac sarcoidosis).

Despite partial improvement to aggressive immunosuppressive therapy, the prognosis is poor but improves significantly with cardiac transplantation.[9][10]

Hypersensitivity myocarditis

A form of autoimmune myocardial inflammation that is often drug related and clinically presents with acute rash, fever, and peripheral eosinophilia.[11] Histologically, it is most often characterized by a myocardial interstitial infiltrate with prominent eosinophils but little myocyte necrosis.[12]

Viral myocarditis with ventricular arrhythmia

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer