Approach

The evaluation of chronic diarrhea can be difficult and effective assessment requires significant clinical acumen. Approach to evaluation is initially for the most common and most serious conditions, adjusting for history and clinical presentation. If the initial evaluation fails to produce an etiology, then diagnosis can be pursued in a systematic fashion in order to search for each differential diagnosis.

Historical and symptomatic considerations

Evaluation begins with a thorough history with attention to symptoms, onset and duration, travel history, concurrent medical problems, diet (e.g., lactose, fructose, gluten, etc.), and medication use.[4] The documentation of stool consistency can be facilitated with the “Bristol stool chart”.[5] Bristol stool chart Opens in new window

The key components of the history include:

Duration of diarrhea: more than 4 weeks in chronic diarrhea[1]

Number of episodes per day: ≥3 loose stools per day in chronic diarrhea[1]

Waking at night with symptoms: makes functional disorders less likely

Presence of blood in the stool: may signify inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), malignancy, or ischemia.

Associated symptoms can include:

Weight loss/failure to thrive (e.g., celiac disease, IBD, malignancy, small bowel bacterial overgrowth, chronic pancreatitis, hyperthyroidism, diabetes)

Abdominal pain (e.g., celiac disease, Crohn disease, malignancy)

Constipation alternating with diarrhea (e.g., IBD, fecal impaction with overflow)

Nausea and vomiting (e.g., small bowel Crohn disease, small bowel bacterial overgrowth, diabetes, fecal impaction)

Hematochezia or melena (IBD, ischemia, malignancy)

Skin changes (celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease).

Additional nonspecific symptoms can include:

Steatorrhea (e.g., pancreatic insufficiency, celiac disease, liver disease, giardiasis)

Abdominal distention/bloating (nonspecific, but beware irritable bowel syndrome and small bowel bacterial overgrowth)

Flatulence (nonspecific, but beware irritable bowel syndrome and small bowel bacterial overgrowth)

Borborygmi (nonspecific)

Anorexia (nonspecific)

Increased infections (common variable immune deficiency, HIV).

Medication use causing diarrhea can include:

Laxative use (may not be volunteered by patient)

Proton pump inhibitors

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

Quinine

Antibiotics (beware Clostridium difficile infection)

Certain chemotherapies and other cancer treatments.[6]

Physical examination

Physical examination is usually nonspecific.

Key findings are:

Skin rashes such as dermatitis herpetiformis, erythema nodosum, and pyoderma gangrenosum are consistent with celiac disease or IBD

Lymphadenopathy or abdominal masses suggestive of infection or malignancy

Blood on rectal exam, which is highly suggestive of a mucosal lesion such as IBD or malignancy.

Laboratory evaluation

Laboratory testing should be individualized for risk factors for disease. For instance, parasitic diseases are uncommon in North America and Western Europe in the absence of travel history.

Basic laboratory tests, which are performed in all patients, include CBC, electrolytes, glucose, liver function tests, C-reactive protein, thyroid function tests, celiac serology, IgA level, and hematinics (B12, folate, ferritin). Fecal calprotectin testing may be considered if available. Fecal calprotectin has been shown to consistently differentiate IBD from irritable bowel syndrome because it has excellent negative predictive value in ruling out IBD in undiagnosed, symptomatic patients.[4][7][8] However, fecal calprotectin can also be elevated in some cases of colorectal cancer, gastrointestinal (GI) infection, or with use of NSAIDs, limiting the test’s specificity.[4]

There are few viral or bacterial infections that cause chronic diarrhea in an immunocompetent host, but certain parasites such as Giardia are common and should be tested for with a stool sample for microscopy, culture, and sensitivity. The number of stool samples necessary to achieve adequate specificity varies with diagnostic modality. A single sample may be adequate using direct immunofluorescence, whereas 3 samples will be necessary for microscopic examination.

Endoscopic evaluation

In the evaluation of chronic diarrhea, endoscopy is a valuable diagnostic tool and is often routinely requested unless other pathology is evident that requires treatment, for example, severe constipation (this also makes mucosal disease more unlikely).[9] Endoscopy allows the prompt visual assessment of disease severity and extent in IBD and can provide prognostic information.

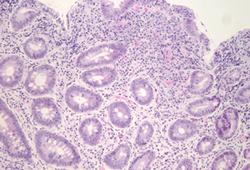

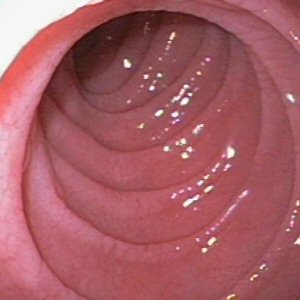

Histologic assessment documents the presence of macroscopic and microscopic colitis. Inflammation on colonoscopy can direct future investigations, such as further small bowel evaluation if Crohn disease is suspected. A negative colonoscopy can allow reassurance to be given to patients who may be concerned they have IBD or cancer. If celiac disease is suspected, a gastroscopy with duodenal biopsies can be obtained at the same visit.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Photomicrograph of villous atrophy in celiac diseaseImage courtesy of Daniel Leffler, MD and Ciaran Kelly, MD; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Endoscopic image of scalloping seen in the duodenal mucosa in celiac disease and other mucosal disorders including giardiasisImage courtesy of Daniel Leffler, MD and Ciaran Kelly, MD; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Endoscopic image of scalloping seen in the duodenal mucosa in celiac disease and other mucosal disorders including giardiasisImage courtesy of Daniel Leffler, MD and Ciaran Kelly, MD; used with permission [Citation ends].

Patients with evidence of GI blood loss, anemia, or significant weight loss should undergo urgent endoscopic assessment of the upper GI tract and large bowel.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer