Approach

The presence of meconium in the amniotic fluid and meconium below the vocal cords are essential criteria to establish the diagnosis of MAS.[1] Infants present with respiratory distress that cannot be explained by anything other than the presence of meconium-stained amniotic fluid (MSAF) and meconium in the trachea.

Although MAS is common in term and postmature babies, it can also be seen in preterm infants, though less commonly. In preterm infants, MAS may be misdiagnosed as respiratory distress syndrome resulting from surfactant deficiency.

Evaluation of the risk

There are several clinical predictors of the risk of developing MSAF and MAS. These risk factors and predictors can be assessed at different stages of the antepartum, intrapartum, and postpartum/neonatal periods to prevent or minimize MAS.

Antepartum

In antepartum evaluation, attention should be paid to the maternal history, particularly the gestational age. A gestational age >42 weeks increases the risk of MAS.[3]

Maternal hypertensive disorders, eclampsia, preeclampsia, maternal smoking, and substance abuse are associated with fetal distress and an increased risk of MSAF and MAS.[3][6][26][48]

Chronic amniotic fluid leakage may lead to oligohydramnios, causing cord compression, which increases the risk of MSAF.[28]

Intrapartum

Intrapartum fetal distress, as indicated by late deceleration, maternal bleeding, the presence of thick meconium, cord around the neck, or a depressed infant, is a sign of the development of MAS.

Postpartum

Thick meconium, a low Apgar score, and a lack of responsiveness to initial resuscitation predict the development of severe MAS.

Physical exam

On examination, infants who are born at gestational age >42 weeks show signs of postmaturity, with green/yellow-colored skin; long, stained nails; dry and scaling skin; postmature appearance; and loss of subcutaneous tissue.

Patients typically have symptoms or signs of respiratory distress such as tachypnea, grunting, cyanosis, and chest retractions (increased work of breathing). Cyanosis may be observed and should prompt immediate intervention.

The chest may be barrel-shaped with increased anteroposterior diameter. Breath sounds may be diminished, and diffuse rales and rhonchi may be present. Asymmetric chest expansion may indicate development of pneumothorax. Tachycardia and hypotension may also be present.

All these signs are usually seen immediately after birth. However, a significant number of infants may be asymptomatic and apparently vigorous at birth and develop severe respiratory distress hours later. Although most aspirations occur in utero, postnatal aspiration may also lead to development of MAS. Clinical presentation includes tachypnea and respiratory distress with cyanosis.[36]

In patients with persistent pulmonary hypertension, clinical presentation includes labile hypoxemia with a gradient in oxygen saturations between preductal and postductal values (i.e., between right upper and lower limbs) greater than 10%.[49]

Initial investigations

Diagnosis of MAS is confirmed by chest x-ray (CXR). Infants with respiratory distress must have CXR in both anteroposterior and lateral positions. It typically shows patchy infiltrations, consolidation, and atelectasis. Pneumothorax or pneumomediastinum is differentiated in lateral views of the chest. In pneumomediastinum, a "spinnaker sail" sign (lifting of thymic lobes) in the posteroanterior view is a typical finding.[50] Asymmetric chest wall and asymmetric movements with decreased air entry suggest pneumothorax. Air leaking is common, leading to pneumothorax or pneumomediastinum. If either of these is present, a CXR should be repeated every 6 hours until resolution.

Laboratory evaluation is indicated to rule out infection and should include a complete blood count, C-reactive protein, and blood culture.

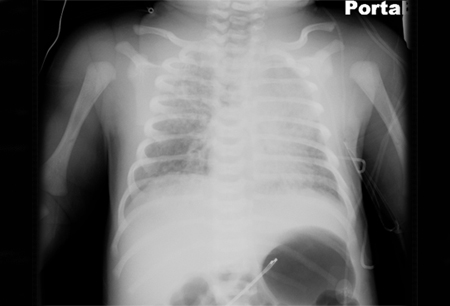

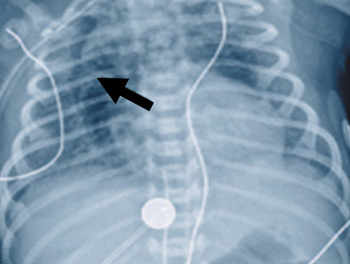

If the clinical evaluation shows mild distress, and laboratory tests are negative, no further testing is required unless respiratory distress persists. Respiratory distress can be objectively measured using the respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) score (e.g., patients with RDS score ≥6 should be immediately provided with respiratory support).[51] Further assessments should be made on an hourly basis.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CXR showing patchy infiltrations on both lungs, suggestive of atelectasis in a patient with MASFrom the personal collection of Dr Vidyasagar and Dr Bhat [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Pneumomediastinum with spinnaker sail sign (arrow)From the personal collection of Dr Vidyasagar and Dr Bhat [Citation ends].

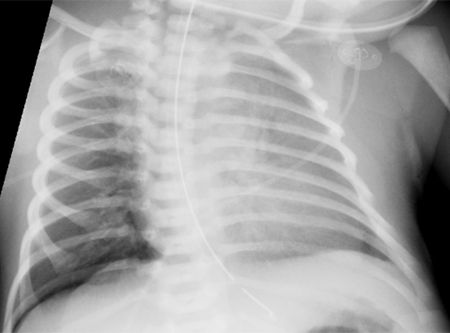

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Pneumomediastinum with spinnaker sail sign (arrow)From the personal collection of Dr Vidyasagar and Dr Bhat [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CXR showing air at the base of right lung above the diaphragm, suggestive of pneumothorax in a patient with MASFrom the personal collection of Dr Vidyasagar and Dr Bhat [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CXR showing air at the base of right lung above the diaphragm, suggestive of pneumothorax in a patient with MASFrom the personal collection of Dr Vidyasagar and Dr Bhat [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Clinical scoring system for assessing the degree of respiratory distress in the newborn. The physician after assessing the baby using the 5 signs in the left column gives a score of 0 (normal), 1 (mild distress), or 2 (severe distress). Scores for all 5 signs are added, a score of 0 being a normal baby and a score of 10 being very sick. Scores in between correspond to mild to moderate distressCreated by Dr Vidyasagar and Dr Bhat [Citation ends].

Subsequent investigations

Arterial blood gases, including pH, PaO₂, and PaCO₂, from the right upper limb and umbilical arterial catheter/lower limb must be evaluated to establish whether a right-to-left shunt is present. This test in full-term infants may help to distinguish pulmonary disease from congenital heart disease.

Infants with severe respiratory distress should be immediately assessed with dual pulse oximetry, with one sensor placed on the right hand and the other on a lower limb. Oxygen saturations with a difference of ≥10% between the right upper limb and lower limb suggests a right-to-left shunt from the pulmonary artery to the descending aorta. This indicates the presence of pulmonary hypertension.[49][52]

An echocardiogram may be performed in severe cases of MAS to rule out congenital cyanotic heart disease and to assess pulmonary vascular resistance.

If neurologic damage is suspected (hypotonia, seizures), a cranial ultrasound and an electroencephalogram should be obtained.

A urinalysis may be ordered in infants with severe hypoxia, as they may present with oliguria or anuria. Hematuria and proteinuria may be present.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer