Etiology

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is a member of the Pneumoviridae family. The viral particle plasma membrane originates from the host cell and surrounds a nucleocapsid. The viral genome within the nucleocapsid consists of a single strand of RNA with 10 genes that encode a total of 11 proteins. Two of these direct viral replication, and the remaining 9 function as structural proteins and surface glycoproteins.[30]

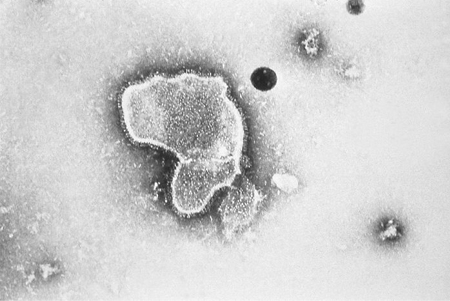

RSV has three surface glycoproteins: fusion protein (F), small hydrophobic protein (SH), and glycosylated attachment protein (G). The F and G proteins are the primary targets for the host's antibodies and therefore play a prominent role in the pathophysiology of RSV. The G protein mediates attachment to the host cell, and the F protein facilitates fusion of the host and viral plasma membranes, enabling transit of the viral RNA into the host cell. The F protein also promotes the aggregation of multinucleated cells by fusion of their membranes, resulting in the syncytia for which the virus is named.[30] The role of the SH protein is less clear.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Electron micrograph revealing the morphologic traits of the RSVCDC/Palmer EL; used with permission [Citation ends].

Pathophysiology

The virus is transmitted by inoculation of the conjunctival or nasopharyngeal mucosa with infected respiratory droplets.[31][32] RSV can remain viable on hard surfaces for up to 6 hours.[33]

The incubation period ranges from 2 to 8 days; 4 to 6 days is most common. [8]

Immunocompetent patients shed the virus, on average for between 3 and 8 days, although this can continue for up to 4 weeks especially in young infants and immunosuppressed children.[8][31][34] Immune deficient patients may shed the virus for 4 to 6 weeks.

Viral replication begins in the nasal epithelium and then progresses downward through the bronchiolar epithelium and types 1 and 2 alveolar pneumocytes.[35][36] The viral infection is generally limited to the respiratory tract with extrapulmonary disease rarely reported.[37]

Viral replication results in bronchiolar epithelial necrosis, followed by peribronchiolar T-lymphocytic infiltration and submucosal edema.[38] There may be a genetic predisposition to severe RSV disease involving mutations to interleukin-4, toll-like receptor 4, and CD14 genes.[39][40]

Viscous mucous secretions, primarily neutrophilic inflammation, increase in quantity and mix with cellular debris.[41] The loss of ciliated epithelium makes clearance of these secretions difficult. The end result is dense mucous plugging of the narrowed airways, producing wheeze, cough, air trapping, and ventilation/perfusion ratio mismatch.

Respiratory virus coinfections are commonly reported, but their impact on disease severity is unclear. One systematic review and meta-analysis found no association between coinfection with RSV and other viruses and clinical severity, except for coinfection with RSV and RSV-human metapneumovirus, where coinfection was found to be associated with a higher risk of ICU admission.[42]

Classification

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer